It was 7 o’clock when I arrived at the Lying Husband. Like Kenton, the pub was quieter than usual for a Sunday evening, with just two people having a beer at the bar. I wondered why.

I saw Agnes and walked over. “How’s business?” I asked.

She made a face. “Not so good. The last several days have seen a big decline in customers. It’s the Cholera. People are afraid to go out. Especially since the Cholera has spread to the west side, which is over there.” She waved in the general direction of the Pacific Ocean. “Now we are between two pestilential areas, with the Cholera coming at us from two directions. No one knows if or how they will get the Cholera, so they are choosing to stay in. And if they have the means, they are leaving town for ‘summer vacation.’ She made air quotes with her fingers.

“Neither,” I said. “Well, maybe the latter. I have been in Kenton all week for work, and I haven’t caught the Cholera. I don’t think it spreads by casual contact.”

The two men at the bar jerked their heads in my direction with that statement. They both set money down on the bar, gulped their drinks, and left in a hurry.

Agnes frowned at me. “Thanks,” she said. “Next time you walk in, just loudly announce you have the Smallpox.”

“I’ll be surprised if anyone shows up for your meeting tonight. I suspect the city will either shut down or empty out or both. People are getting spooked. Either you are a man of rare courage or great stupidity to be out and about during the Cholera.”

“Sorry. Really. I didn’t mean to drive away customers. Maybe I am stupid. And why aren’t you running away?”

“Forget about it,” she said. “It is not like it is going to make any difference if I leave. Just try and be careful next time. I had the Cholera in 1999. I survived it, obviously. But they say you can’t get it twice, so I should be safe if you are able to pass the Cholera on to me.”

“I suppose,” I said. “Still, I think you are the courageous one.”

She snorted. “Now, what will you have?”

“A pint and fish and chips.”

“You are consistent. It might be a bit of a wait,” she said, sweeping her arm across the empty pub. “What with all the business and all.”

I smiled sheepishly. “I said I was sorry.”

“I know. But I can’t resist a dig. Make yourself comfortable.”

She poured me a pint, and I went to a table in the back of the bar and tried to relax.

The Cholera was affecting the city more than I realized. I had been paying so much attention to the trees that I never saw the forest. Fear of the Cholera was widespread and was growing, especially as the number of cases increased. The Times was not helpful; the newspaper reports were not very reassuring, playing up the relentless increase in the number of cases. But then what else could they do? Lie? Nothing had been discovered or reported that would give anyone comfort. And the Medical Societies were doing what they always did, CYA.

I drank my beer quickly and signaled for another. Agnes brought it right away.

“Tough day to drink a beer that fast.”

“You don’t know the half of it.”

“It will pass, love.”

“Yep. Like the Cholera flux.”

She left and returned shortly with my dinner, which I ate slowly as I sipped the second ale. I did not want to have a foggy brain when the meeting started. Shortly before 8 o’clock, Bonham entered the pub.

“Business is picking up. Welcome, sir,” said Agnes. “What can I do for you?”

“I’m with him,” he said, pointing to me. “And I’ll take a pint of ale, please.”

“Lucky you and coming right up.”

Bonham made it to my table at the same time as the beer. We clinked glasses and took a sip.

“So, what’s the plan?” he asked.

“The meeting starts at eight. But if Agnes there,” I pointed at the bar, “is right, then it might just be you and me. Everyone is too afraid of the Cholera to leave their houses or, if they were able, have fled the city.”

“I thought downtown seemed a bit quiet for a summer evening,” he said. “It did not occur to me that it was because of the Cholera.”

We sipped our beers in silence while I watched the door. Eight o’clock came and went. Then at 8:05, Darin Boyles walked through the door.

Of course. A person who is dying of the Consumption has no worries about the Cholera. I waved him over and introduced him to Bonham. “Well, Darin. We are likely it. The fear of the Cholera is keeping people away tonight.”

“I figured as much,” said Darin, who ordered a pint. “I was here during the 1999 outbreak. When the cases spread beyond their initial source, the same thing happened. Everyone either stayed home or left the city. Once there were about three hundred cases and a couple of Chiropractors died all the Medical Philosophers skedaddled. You could not find a Society member to care for anyone, much less the Cholera patients. Everyone got spooked, and the city shut down. Who knows what would have happened if the Cholera hadn’t abruptly ended? Portland would likely have become a ghost town.”

“Where was the 1999 outbreak?” Bonham asked.

“Mostly in Ladd’s Addition. At least that is where it started. Then it spread to the west side, Beaverton. They never did figure out why. Then we had a cold snap, and the Cholera went away. But the city remained jittery for a long time. I’d say it was a couple of years in getting back to normal.” He took a drink and looked at the clock. It was now a quarter past the hour. “Well, if it just us three, let’s talk. I have some interesting information about the Cholera.”

“Go ahead,” I said.

“I have been looking into reports from other chapters of the Order. I put out a request for any historical or other information from any of the archives concerning the Cholera. It took a while, but I was sent a bit of history that could be very important.”

“You probably do not know this, but there was an outbreak of the Cholera in Haiti in 1897, back when it was still French. The Crown acquired the island as part of the Spanish Caribbean War in 1898, right after the Cholera ended. At the time, there was extensive documentation of the outbreak and the French approach to controlling it. Those records were discovered and moved to the Philadelphia chapter of the Order. It looks like a military surgeon, a Royce O’Loughlin, came across the reports as part of his official duties as the head of a hospital. He was also a member of the Order. Rather than give the records to the Crown, which would have suppressed the information, he kept them.

“I suspect given how the Crown frowns on anything Continental, he took the opportunity to preserve any information he stumbled across. It looks like when we took over the island, most of the official French records were either confiscated or destroyed. So, he kept these records, assuming them to be valuable. When he went home to Philadelphia, he brought them along and gave them to the Order. He died shortly after that of Yellow Fever. And they have been sitting in the archives ever since, unread. When I asked for any information about the Cholera, the chapter Secretary had recently found the report and skimmed it. She thought it might interest us, so she sent me the papers by express. They are translations from the original French.”

He reached into a satchel and pulled out a binder of papers. “It came only this afternoon, but I looked it over quickly.” He held out the papers to me. “They did not have a cure, and they did not know how the disease was spread, but they had a treatment, a simple treatment that brought the mortality rate from forty percent to two percent. And it has been sitting in the Philadelphia Chapters basement all this time. Who knows how many lives could have been saved in the last hundred years if this information had been disseminated instead of gathering dust in Philadelphia? Sort of ironic. Instead of being suppressed by the Crown, it was hidden by accident. Same result. But you have to wonder how much valuable information is hidden away in Crown archives or simply burned, never seeing the light of day. The lack of open, available knowledge has likely killed more than the Cholera.”

“Seriously? Two percent mortality?” I said. “That is incredible.”

“I’m as serious as a hanging.”

I took the papers. “What did they do?” I asked.

“Very simple. It looks like they reasoned that the diarrhea of the Cholera is like saltwater. Someone, lucky guy, measured chemical levels in the stool of Cholera victims. It was full of sodium, potassium, and bicarbonate. Like ocean water. So, they had Cholera patients drink ocean water. Initially it did not work because no one could tolerate straight seawater. They added vomiting to the flux. Not so good. So, they diluted the seawater four-to-one in sugar water to make it more palatable. Patients had to drink the same amount of sugared seawater as they shat out. And it worked. Almost no one died of the Cholera as soon as they took the ocean water cure.”

“That’s just hard to believe,” I said. “That something so simple could be so effective.”

“Read it. See for yourself. They had no reason to make it up. They have the numbers before and after. Seems pretty compelling to me.”

“Well,” I said. “I’m going to have to read this a bit later. But if it is as you say, this could save hundreds of lives.”

“The only problem is,” said Darin, “We are ninety miles from the ocean.”

“I would bet good money that once this is known, people will find a way to get seawater shipped to town. At premium prices as well. But first we have to publicize this. I have a meeting tomorrow morning with the Times; I will let them know. And the River Weekly. This has to be published ASAP.”

As I finished speaking, the door opened, and I was surprised to see both Cassandra and the Ford sisters enter the pub. They waved at us and came over.

“We have,” Cassandra announced, “a breakthrough.”

The Ford sisters nodded their heads in agreement.

“Let’s move over to a larger table. Sit down and tell me.”

As we moved over, more food and drink were ordered. We still had the pub to ourselves.

“If you need us to move upstairs, so we don’t scare anyone off,” I told Agnes. “Just let us know.”

She shook her head. “This is the most business I have had in days. I doubt it will be a problem.”

I quickly told them about the seawater treatment and asked what breakthrough was.

“I’ll let the Grace or Allison tell it,” Cassandra said. “It is their work that led to the result. I was just the data mule.”

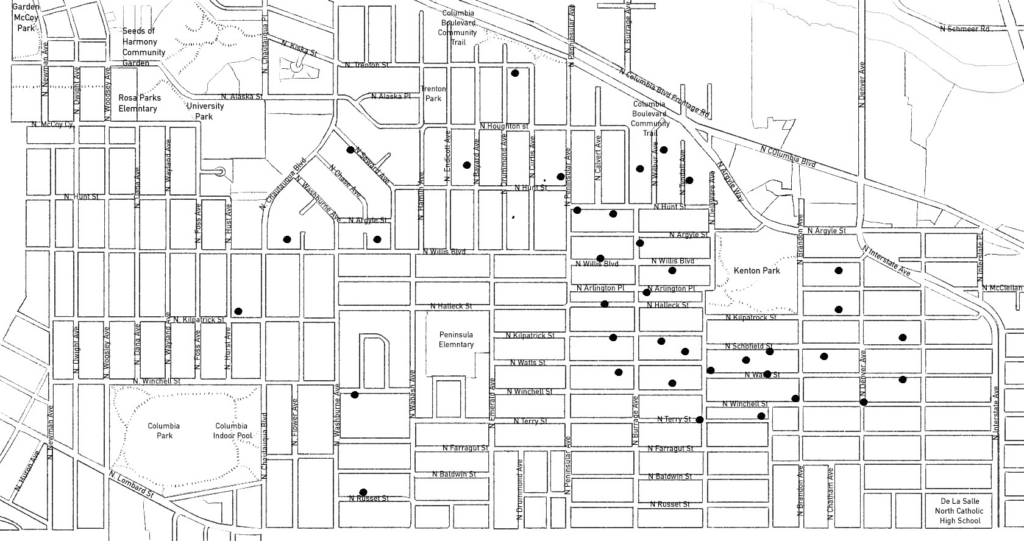

When they were seated, Grace opened a satchel and pulled out a single piece of paper. On it was a map of the Kenton neighborhood, covered with dots. I looked at the sisters and raised an eyebrow.

“Let us tell you what this means. We looked at the information provided by you and the reports looking for a pattern, running it through the UKM. We were looking for relationships that might give a hint as to what is causing the Cholera or how it is spread. We found two. This is a map of Kenton. Each dot represents cases of the Cholera. What do you see?”

“A lot of dots,” I said. “A lot of Cholera. I knew that.”

“Don’t look at the dots; look at the pattern of the dots.”

I looked again. What did she want me to see?

“Notice how the dots are distributed?”

“Maybe,” I said hesitantly.

“I see an arc,” said Bonham. “Three quarters of a circle.”

“Excellent. You have a good eye. The UKM was programmed to take these points and find a line that describes all the points.”

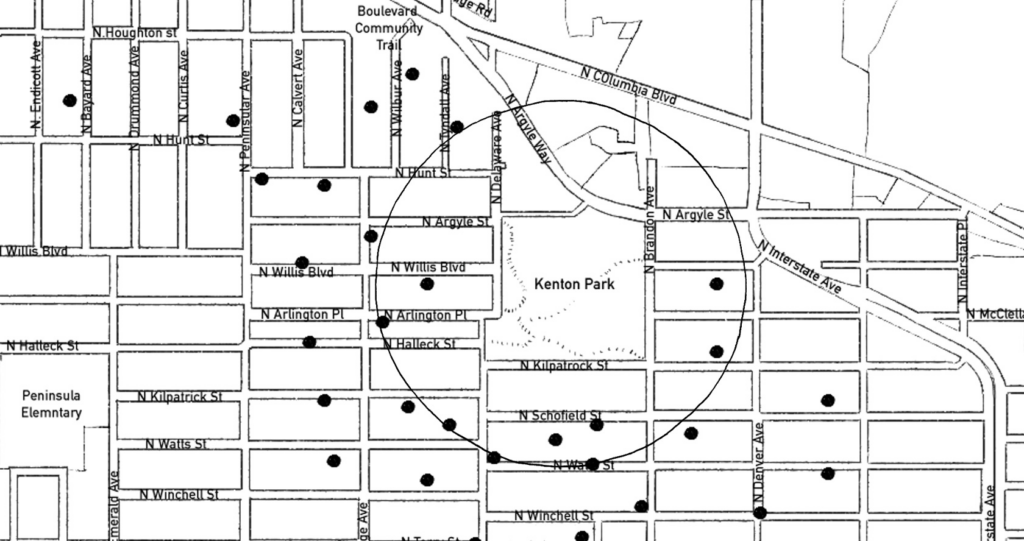

She pulled out another piece of paper.

This was another map of Kenton, but instead of dots, there was a dark line making a circle.

“So, what does that mean?” I asked. “What does this circle mean?”

Again, Bonham spoke up, very excited. “What a circle means is that every case is the same distance from a central point—the center of the circle.” He stuck his index finger on the map. “Right about there.”

“Exactly,” said Allison.

We all looked at the map. His finger was in the center of Kenton Park, near the foot of Paul Bunyan.

“What’s there?” asked Allison.

“Just a park that used to be an old farm,” I said. “It was a commons for a while when the neighborhood started. Now it is just a nice expanse of grass. Nothing else there but an old water pump that people like to use to get natural water instead of the tap water.”

Everyone stared at me.

At the same time, everyone said, “It’s the water.”

“No way,” I said. “That pump has been used for a hundred years or more, and there has never been a problem with the Cholera in the Kenton neighborhood in the past. So why now?”

“That,” said Bonham, “Is what we have to figure out.”

“It’s a start,” I said, “But it does not explain how the Cholera jumped twenty miles east. The only way I can see for that to happen is for a bird or other flying animal to transport it to Lake Oswego or Hillsboro. I can’t see how a bird would be able to operate the pump, fill a canteen, and take it to those cities.”

“Maybe, maybe not,” said Allison. “That is a nice transition into our other discovery. The UKM found another association. The distribution of the type of care received is mostly the same. There are a few outliers, but most people who sought care for the Cholera received that care from one of the Five Societies, with a bump in disease in those who received care from a Homeopath. But. Those with Cholera who received preventative care were much more likely to have seen a homeopath. And both the cases in West County had seen homeopaths.”

Bonham jumped in again. “And homeopaths treat most everything with water.”

Allison pointed at Bonham. “That one,” she said, “is smart. I would not lose him.”

“That’s just great,” I groaned. “The Homeopaths are responsible for the spread of the Cholera. That is going to go over really well. Tomorrow, I have to let it be known that seawater mixed with sugar water is the treatment for the Cholera, see if the water pump in the Kenton Park is the source of the Cholera, discover a hitherto unknown animalcule, and blame the Homeopaths, perhaps the most powerful Medical Society in the city, for the Cholera on the west side. While I am at it, I shall also try for world peace.”

“Well,” said Cassandra. “At least it will not be boring.”

I looked at my watch. It was only 7:45.

“If we are done, who is up for a field trip?” I asked.

“A field trip?”

I explained the healing water/baptism that was going to occur at sunset at Kenton that evening.

“Now that we have a hint that perhaps the Cholera is spread by water, I thought I would observe. Anyone up for joining me?”

Bonham was the only one, the others begging off with work to do. We paid Agnes.

“Come again soon,” she said. “I could use an income, no matter how small.”

Bonham and I rode the tram to Kenton, reading the reports from the Haitian Cholera outbreak.

It was compelling, if incomplete, evidence for the saltwater and sugar cure. Deaths became rare as Cholera sufferers drank the concoction. It was an interesting observation that the composition of the Choleric diarrhea was the same as seawater. Was there something in seawater, or was it replacing the patients’ lost salt and water? There was no mention or even hints that the cause of the Cholera was an animalcule. How would an animalcule lead to the massive loss of salt and water described in the Haitian reports? If animalcules were indeed the cause of the Cholera. And could it be there was something in the seawater that killed animalcules? Is that even possible? A substance that could kill an animalcule without killing a human? That seemed far-fetched as well. Every potential answer resulted in dozens of new questions.

The trolley came to a stop in Kenton, we got off and walked over to Paul. It was a pleasant evening, although the area was still mostly empty of traffic. Kenton Park, however, had a crowd of around a hundred people down by the water’s edge. The only other people in the park were people at the pump, filling containers with water and taking it to the crowd.

We walked to the crowd and soon could hear a man speaking. Dressed in black and white, with a preacher’s collar, he said, “Brothers and Sisters, it is nearly sunset and, therefore, time to begin.” He spread his arms and tilted his head back, looking at the sky as the crowd quieted. “Father in Heaven, we beseech you. The Cholera is spreading through our city, sickening and killing your children. We pray for your assistance.”

He lowered his arms and looked at the crowd. “Brother and Sisters,” he continued, ’thank you for coming. Times are bad. A plague has begun in our good city. God has sent plagues before, plagues of water turning to blood, plagues of frogs, of lice, of flies, of livestock pestilence and boils and hail, and locusts, and darkness and the killing of firstborn children. Now God has sent us the plague of the Cholera. But why, you ask?”

He paused and surveyed the crowd, then spread his arms. “Because you have lost the faith, a faith in the glory of God, and strayed from His Word. You have sinned against God and God’s law, and the punishment of sin is the Cholera. To stop the Cholera, you must return to the Lord our God, to be baptized in the water, and open your heart to the Lord. Then and only then can the Cholera be defeated.”

He clasped his hands together and looked into the sky. “Heavenly Father, we beseech you. We have strayed from Your glory, and we ask for forgiveness. For as it says in the Bible, He who believes in Me, “From his innermost being will flow rivers of living water” and “whoever drinks of the water that I will give him shall never thirst; but the water that I will give him will become in him a well of water springing up to eternal life.”

He looked at the crowd again. “Here is the water. Come, be baptized, and be forgiven.” He leaned down and picked up a jug. “Drink of this water, this holy water, this blessed water and never fear the Cholera, or any illness again. Praise the Lord.

“Who will be first to be blessed in the holy water and drink the water?”

A shout went up from the crowd, and the preacher waded into the water to his thighs, followed by a young man, who was dunked in the slough to the cheers of the crowd while the preacher said, “Having been commissioned by Jesus Christ, I baptize you in the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Ghost. Amen.”

He then went to the shore where a young woman dressed in white offered him a sip from a jug.

We watched the spectacle in silence for around half an hour, then, with a nod, left.

“Well,” said Bonham. “If there are Cholera-causing animalcules in either the pump water or the river water, we are going to see a jump in cases in a few days.”

“A hundred additional cases. Just what we need.”

I sighed and told Bonham we were meeting up at Paul Bunyan tomorrow after my meeting with the Times reporter. We had a pump to examine.