One longstanding topic of this blog (and my not-so-super-secret other blog) has been the discussion and evidence-based discussions of why so-called “alternative cancer cures” are not cancer cures and “alternative cancer clinics” peddle quackery. Of these, the Burzynski Clinic in Houston has featured on this blog a lot since 2011 or so, because discussing the “discovery” of its founder, Polish expat Dr. Stanislaw Burzynski, has provided excellent fodder to discuss why “alternative cancer cure” testimonials are almost never good evidence of efficacy, the manipulation of clinical trials by quacks, and how toothless state medical boards and the FDA have long been trying to stop these cancer quacks, such that after nearly five decades, Burzynski is still preying on cancer patients selling his antineoplastons and a “make it up as you go along” grab bag of expensive (and legitimate FDA-approved) targeted therapies, sold by a pharmacy in which he had a stake, as well as his “rebranded” orphan drug. Of course, the US is not the only country with these clinics. They can be found in Germany, Mexico, and many other countries as well and have existed for a very long time, with authorities in these countries seemingly unable or unwilling to shut them down.

One common characteristic of quack cancer clinics is that they often combine evidence-based cancer care like chemotherapy and immunotherapy with quackery, using the legitimacy of evidence-based treatments to make the quackery seem evidence-based as well. Sometimes, they also offer experimental therapeutics that have not as yet achieved regulatory approval by the FDA or other bodies in other countries responsible for approving drugs for use outside of the context of a clinical trial, although in some cases the quacks running the clinic set up legitimate-seeming clinical trials to use as an umbrella under which to sell their snake oil. Again, all of this is very expensive, and often patients at these clinics are driven to sell off possessions and utilizing crowdfunding to finance their treatments.

But how do these clinics attract their marks? It’s often word-of-mouth, but these clinics also actively recruit patients online with slick websites and large social media presences, which brings me to the topic of this post, a recent study published in BJC Reports by Marco Zenone et al entitled Alternative cancer clinics’ use of Google listings and reviews to mislead potential patients. This study illuminates how alternative cancer clinics manipulate Google reviews to provide a false sense that their treatments work by cultivating favorable online reviews.

Let’s take a look.

Google and alternative cancer clinics

The study examines unexplored means by which alternative cancer clinics shape their appeal using Google search results and Google reviews. Basically, what the authors did was a content analysis of the Google listings of 47 alternative cancer cure clinics using Google entries and reviews collected on August 22, 2022. I note that that date was almost two years ago, which makes me wonder what took so long to get this study published. I speculate, based on my experience trying to get manuscripts like this published that they had difficulty and likely submitted to more than one journal after rejections. Basically, journals are leery of publishing studies like this, no matter how well done. In any event, the authors justify their approach after a discussion of the nature of alternative cancer clinics that offer “unproven, disproven, and questionable treatments with worse clinical outcomes than evidence-based cancer services [1, 2]”:

Alternative cancer clinics face several challenges in their attempts to attract potential patients. Regulators at different branches of government have attempted to regulate predatory alternative cancer treatment marketing [11,12,13]. Some such clinics have received negative news coverage that asserts they offer ‘false hope’ and ‘misleading’ treatments to persons in desperate situations [14, 15]. Dedicated blogs by qualified medical professionals warn against their treatments [16, 17]. Increasing research activities and attention to alternative cancer treatment outcomes put the spotlight on the questionable practices of many such clinics [1, 2]. Certain alternative cancer clinics are subject to lawsuits from prior patients [18, 19]. In some cases, the families of persons who tried alternative treatment, and died, warn others of the risks [20]. Conventional cancer information authorities warn against alternative cancer treatment services [10, 21].

Leading to this rationale:

An unexplored means where alternative cancer clinics can shape their brand is their portrayal across web search results. Google listings, which provide a summary of a business, location, or person, also provide descriptive information on the purpose of a business. This information is often the first point of contact by a Google search user Googling the name of a business. For example, if prospective cancer patients search ‘clinic xyz’, they will see a clinic description. Businesses control how they identify themselves and appear to users [24]. For an alternative cancer clinic, whose services are unsupported by authoritative medical bodies, this can lead to opportunities to self-declare as a qualified organization for primary cancer treatment. A prospective patient seeing such information may as a result have a distorted impression of the clinic.

Additionally, search results contain Google reviews, where previous clients of a business can post a 1-to-5-star rating of their services and a text explanation outlining their rating rationale. For alternative cancer clinics, reviews are an important indicator to prospective patients about the quality of services and experiences of former clients.

Noting that the “information environment provided by Google listings and Google reviews may contribute in part to misleading potential cancer patients about alternative cancer clinic qualifications, reputation, and treatment efficacy” and that “results can inform health policy to deter cancer patients from receiving unproven care and support advertising regulators to understand an unrecognized form of unproven medical advertising” the authors note that they sought to answer the following questions:

- How alternative cancer providers’ expertise and qualifications are portrayed in their Google listings.

- How clinics are rated across their Google reviews.

- For what reasons and outcomes Google reviews are rated positive (score 4 or 5) or negative (score 1 or 2).

- If reviews contain an action statement recommendation to receive treatment from the provider

- Who is making the reviews and in what situations.

- If reviews contain evidence of reputational management.

The authors did not seek to cover all alternative cancer clinics, but rather the most prominent clinics that tried to recruit English-speaking patients, using clinics identified in an earlier study:

We sought to identify clinics which primarily offered as a key service, alternative cancer treatment. We retrieved a list of 47 alternative cancer providers identified in a previous study investigating how alternative cancer clinics market their services across paid Facebook and Instagram advertisements [8]. The study retrieved their list from a patient directory of alternative cancer clinic options (HealNavigator.com) and a study that investigated treatment destinations named where prospective cancer patients fundraised for alternative cancer treatment [3]. Taken together, our alternative cancer clinic identification strategy retrieves clinics actively courting patients online and with a vested interest in positive online portrayals.

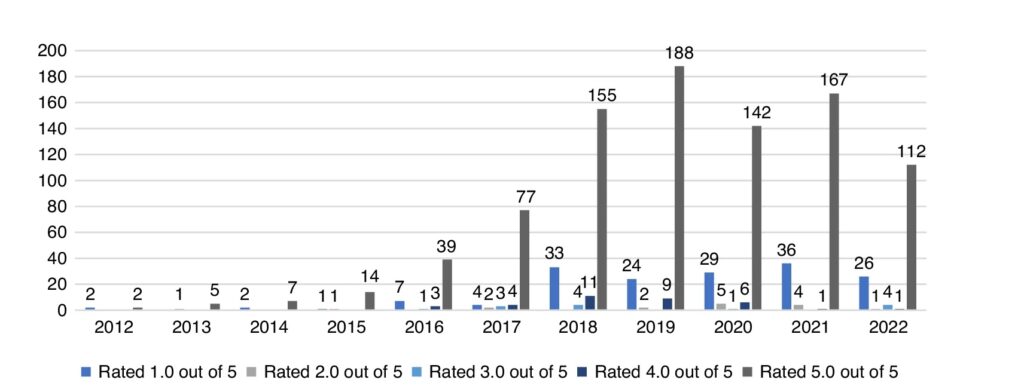

So what did the authors find? First, they noted that most of these clinics didn’t declare themselves to be alternative cancer clinics. Indeed, of the 47 clinics, only 6 (12.8%) reported their clinic “alternative,” whereas 39 (83.0%) were labeled a cancer/medical clinic or hospital, while in two (4.3%) cases, clinics were not labeled or had another unrelated label. The clinics were also, by and large, given high ratings, with the average clinic having received 4.42 stars (median, 4.5; highest score, 5; lowest score, 3.2), represented graphically here:

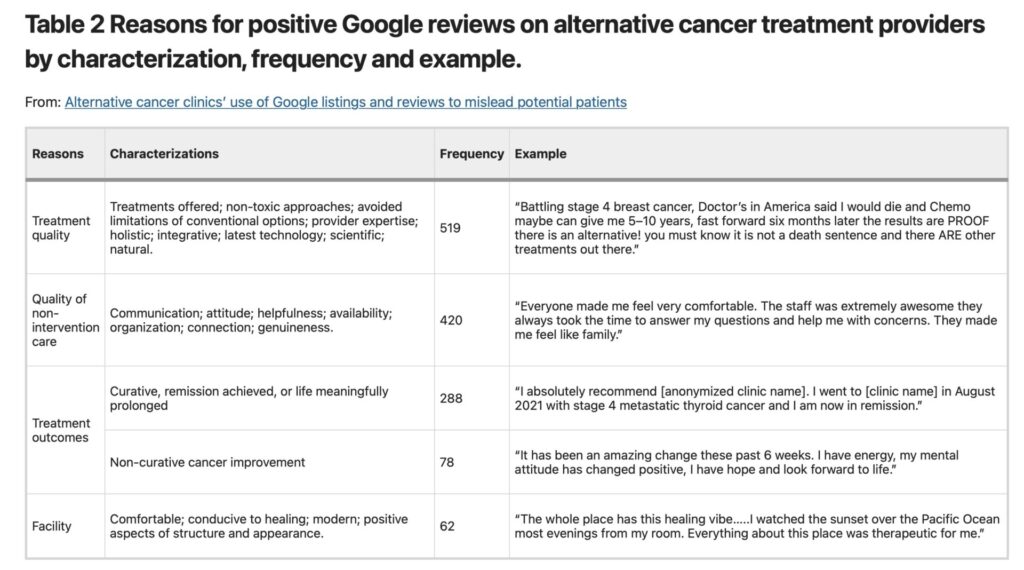

Here are the most common reasons for positive reviews, most including improvement, the doctors, and the “holistic” nature of the treatments used:

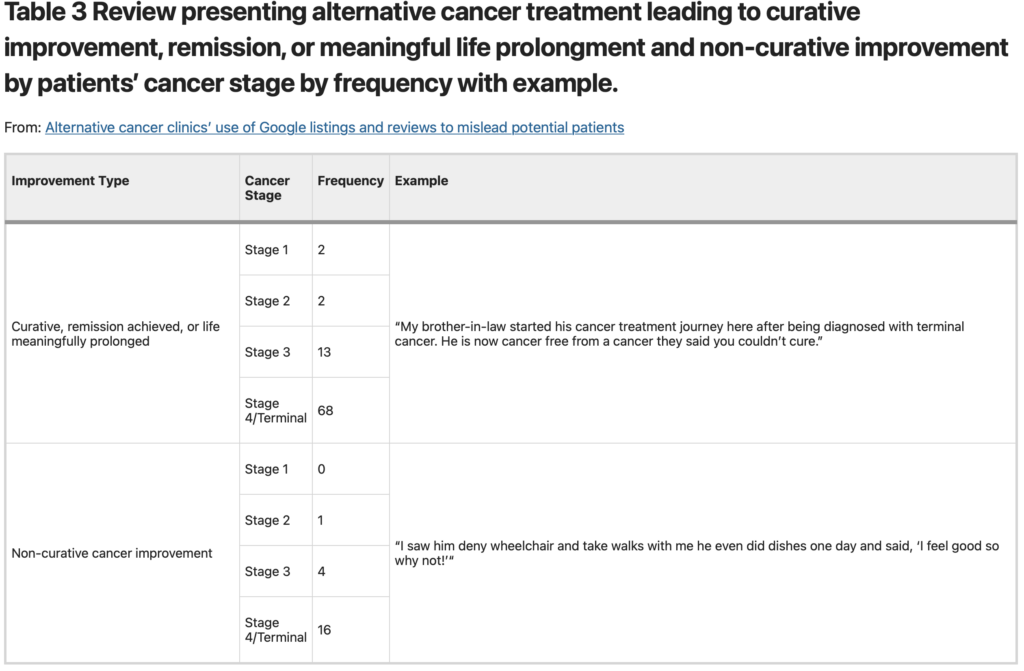

You’ll note that the first example tells us nothing. The patient with stage 4 breast cancer was only six months out from her diagnosis. As I’ve said before, it’s common for patients with stage 4 breast cancer to live 6 months, even a few years. Indeed, whenever I discuss alternative cancer cures for breast cancer, I like to cite a 1962 study of the natural history of untreated breast cancer, which showed that even those with advanced disease occasionally can live more than ten years without treatment. Of the 1,444 Google reviews examined, only of the positive reviews 288 touted improvement in their cancers (e.g., remission) as a reason for the positive review, with some of the claims summarized below:

You’d think that, if (as they claim) these clinics were curing so many advanced stage 4 cancers, most of the reviews would be touting “miracle cures,” but they are not, which suggests to me that these clinics do not actually cure stage 4 disease, leaving most of the rest of the 1,444 positive reviews to focus on other things.

Specifically, reasons for positive reviews not related to improvement in cancer status included:

- The treatment avoided the adverse impacts and limitations of conventional cancer care (for example, the harms of chemotherapy or radiation) (n = 146)

- The treatment approach was holistic, whole-body, and integrative (n = 83)

- The treatment was personalized to the patient (n = 69)

- The treatment used the latest scientific or technological advancements (n = 43)

- The treatment focused on natural approaches to healing vs. pharmaceutical strategies (n = 18)

This is all very well and good, but none of this tells us if the treatments offered by alternative cancer clinics actually work against any cancer, much less advanced cancers that these clinics claim to treat and cure.

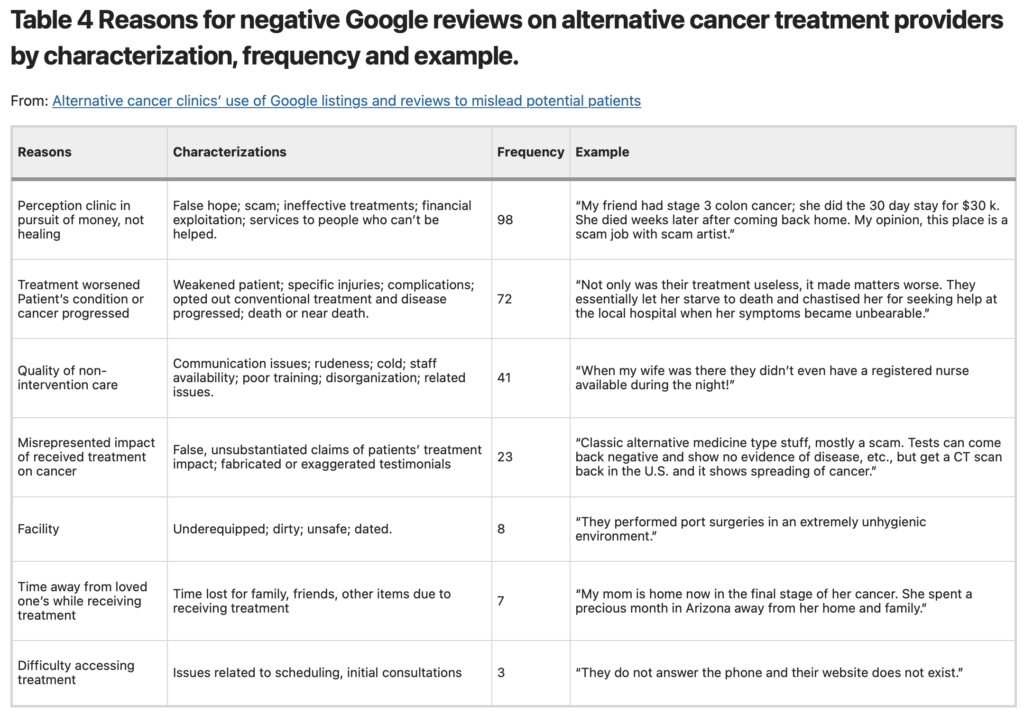

What I was interested in, though, were the negative reviews. The positive reviews and alternative cancer cure testimonials are expected. They are part and parcel of clinics like this, whether the testimonials spread via Google reviews, elsewhere online, or word-of-mouth. There were a total of 188 negative reviews, which, interestingly, came mostly from the families of patients (n = 60), with very few reviews coming from patients themselves (n = 17). One can speculate as to the reason for this, but based on my experience writing about these clinics I can speculate a bit. First, patients can’t provide testimonials in the form of Google reviews if they are dead. Second, I’ve seen how much patients come to believe that their choice of quackery helped them, even when objective evidence is clear that it did no good or even harmed them; likely, few patients are willing to admit publicly that they had made a horrific mistake.

Whatever the reasons, the entries on this table will be familiar to readers of this blog, as these are common features of quack cancer clinics:

The surgeon in me winced at the comment about placing ports under less than sanitary conditions. Ports are implantable intravenous devices with a port just under the skin that can be used to administer medications and to draw blood. They need to be placed under operating room-level sterile conditions. Port infections are no joke. There rest of the complaints are pretty typical practices of these clinics, in particular making false claims of efficacy for the treatments offered and, once they have the patient’s money, ghosting them and their families.

It also turns out that these clinics do online reputation management. (Quelle surprise.) The results:

Alternative cancer clinics responded to 35 negative reviews to dispute reviews detailing improper conduct. Clinics often sought to refute that their interventions did not work and that their providers were not qualified (n = 16). In response to patients’ condition worsening or dying, clinics stated that patients die due to aggressive or terminal cancers even when helpful treatment is offered (n = 8). In more aggressive rebuttals, clinics asserted that (1) negative reviews were fraudulent (n = 7); (2) that they do not make promises about treatment efficacy, promises of recovery, and that they only take patients they can help (n = 7); (3) it was the result of patients actions, not their own, that their situation not did not improve (n = 6); and (4) clinics do not lie about improvement or fake testimonials (n = 4). In softer rebuttals, clinics: (1) offered sympathy and prayers (n = 13) or (2) shared their institution’s history (n = 6). Sometimes, clinics apologized and made offers to correct the situation (n = 6). Rebuttals and responses are summarized in Supplemental Information File 3.

Among positive reviews, we found evidence certain Google reviews challenged negative reviews (n = 21). Here, reviews referenced the negative reviews and provided a rebuttal. For example, a review for [anonymized clinic name] hospital states: “I saw a post here talking about people being promised a cure. That is a lie. I have NEVER heard ANY of the doctors promise anybody a cure. That is completely asinine and really ticks me off that someone would lie like that in the comments!” It is not possible to state whether the reviewer had an affiliation with the clinic.

Again, does this sound familiar? In particular, blaming the victim is part and parcel of quacks. Basically, if the snake oil they conned you into purchasing doesn’t work, then it must have been because it was your own fault for not doing what the quack said, for not following the instructions closely enough. (One example in the study: “We know how to save lives of cancer patients, but only if they take our advice. Staff has confirmed several points of dispute between us and the patient.” How awful can these people be?) I also like the part about quacks denying that they made promises about efficacy of their treatments. In a pedantic way, that is usually true, but only because quacks always leave themselves some wiggle room, some plausible deniability regarding their claims of efficacy.

What can be done?

The authors conclude their discussion of their findings with several recommendations. First, they note that they don’t think that Google is intentionally allowing this situation to continue, noting that ” its systems are actively abused with limited, potentially negligent oversight.” Personally, though, I’d say that if Google doesn’t do anything to remedy this situation, it is complicit with the cancer quacks running these alternative cancer clinics. Still, it’s worth looking at the authors’ suggestions:

- Alternative cancer clinics should not be allowed to label themselves as conventional cancer providers. While I agree with this, I do wonder how Google could manage something like this, given that deciding if a cancer clinic is “alternative” (i.e., quack) or not is a judgment that an algorithm or AI is not likely to be able to make, and we all know how much Google tries to keep human judgment to a minimum because humans are expensive to hire.

- Warnings should be placed on questionable medical advertisers with linkages to qualified sources of information, such as the American Cancer Society or conventional health provider organizations, such as the American Medical Association. This is a good idea. The American Cancer Society used to keep a listing of unproven methods of cancer treatment that explained why treatments such as, for instance laetrile and antineoplastons, don’t work.

- Google should not recognize alternative health professions, such as naturopaths or chiropractors, with the same status as conventional health provider groups, such as nurses, physicians, physiotherapists, and occupational therapists, when making content decisions. Yes! Unfortunately, it might be difficult to do this, given how many states now license chiropractors and naturopaths. These pseudomedical professions have been working for decades to appear more legitimate and, unfortunately, have been pretty successful at it.

- Google should warn people reading medical clinic reviews that reviews are not substitutes for medical advice and that Google cannot confirm the veracity of claims. I would be in favor of this for all medical clinics, legitimate and quack.

- Google should cease other business activities with alternative cancer clinics’ use of Google products, by, for example, demonetizing their YouTube accounts, prohibiting their use of Google ads, and reducing search result priority. Google has done this in the past with certain websites, such as when they delisted Mike Adams’ website, resulting in plummeting traffic from search and decreasing sales. They did the same thing with Joe Mercola’s website, with similar results.

I’ve long known that alternative cancer clinics are an indictment of our system of regulating medicine, given that they continue to exist and bilk patients despite the ineffectiveness and expense of their treatments. Google acted over the last several years to try to limit the reach of these sites and to keep them from easily monetizing their content as they attracted patients. After that, it seems that it has done little. Google can do better, but I fear that it might choose not to, because it would cost effort and money.