It just struck me the other day that, in less than a year and a half, I will have been at this blogging thing for two whole decades. I’ve been writing for SBM for over fifteen and a half years, having started my first blog more than three years before that and having been active on Usenet countering quackery and antivaccine pseudoscience for five or six years before that. (Yes, I’ve been at this in one form or another since the late 1990s.) I was reminded by a recent spate of laudatory (or at least very unskeptical) stories about Neko Health last week touting their “lofty promise of preventative healthcare via full-body scans backed by AI software” of the very first time that I actually put my then relatively recent turn to combatting dubious medicine into action with respect to a medical fad that had been going on for quite some time, that of whole body scans for preventative healthcare.

Reading some of these stories, I immediately felt a profound sense of what Yogi Berra would have called “déjà vu all over again”:

Neko Health, a healthcare technology company co-founded by Hjalmar Nilsonne and Spotify founder Daniel Ek, announced the successful completion of a €60 million ($65 million) series A funding round. The company aims to revolutionize the health industry through artificial intelligence (AI)-driven full-body scans, specifically focusing on preventative healthcare.

Do tell. What, exactly, does this “whole body scan” involve? Let’s find out:

Neko Health has introduced an innovative medical scanning technology that enables extensive and non-invasive health data collection, prioritizing speed, accuracy and convenience.

The company operates private clinics with proprietary and off-the-shelf diagnostic products, including its own 360-degree full-body 3D scanner integrated with over 70 sensors. The scanner can collect 50 million data points within minutes.

This data undergoes analysis by a “self-learning AI-powered system,” providing doctors and patients with insights.

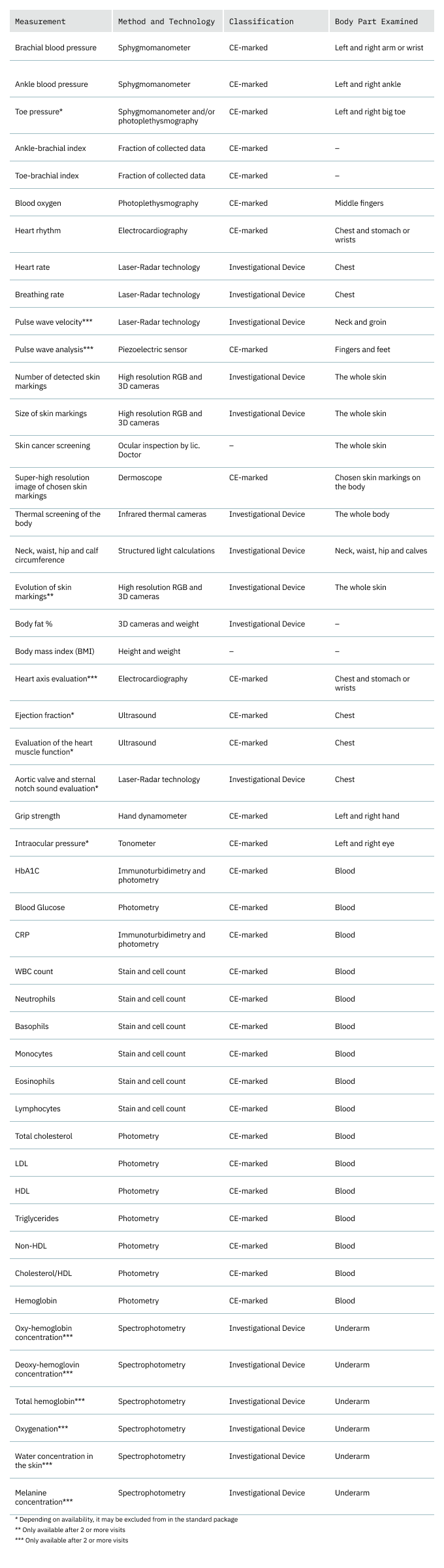

So Neko Health is a bit more than what I dealt with, lo, those many years ago. Clearly, the industry hawking “whole body scans” as a health panacea has evolved since I last seriously dealt with these products. Two decades ago, when I first started complaining to a local NJ radio station about ads by a company called AmeriScan making unrealistic and extravagant claims for “whole body scans” and “screening MRIs” that’s all it was, CT scans and MRIs. Now it appears that “whole body scans” involve so much more, both a proprietary “its own 360-degree full-body 3D scanner integrated with over 70 sensors” and a raft of other test, to the point that it reminds me very much of how I once described “functional medicine”: reams of useless tests in one hand, a huge invoice in the other. the only difference being that companies like Neko Health add artificial intelligence to the mix, because it’s the latest tech fad.

In fairness, the invoice for Neko Health’s “whole body scan” isn’t that huge (€250), but it’s still at least not insubstantial. None of this changes my perception that Neko Health simply represents the latest iteration that, consistent with the latest tech fad of the times, just adds AI to a very old idea, that some variant of “whole body scans,” whatever the form they take, is a magical tool for finding disease super early and managing health.

You think I’m being unfair by using the word “magical”? Take a look at this LinkedIn post by one of the company’s founders, Hjalmar Nilsonne:

Again, the sales pitch is very much like the sales pitch favored by practitioners of “integrative medicine,” including naturopaths and “functional medicine” practitioners, representing their methods as The One True Preventative Medicine. I note that, among the many commenters praising Neko Health, there was one commenter who exhibited the appropriate level of skepticism, a question that I will expand on as I look at Neko Health’s product and products like it:

Instead of alleviating pressure on our health systems this will probably just add to it. All scans find ‘something’, will Neko help ‘solve’ them or just refer the patient to the already struggling general practitioners and public hospitals?

Excellent question, Mr. Bateman! Did Nilsonne answer it? Nope. Only one person did, and he appears not to be affiliated with the company:

Why rely on human eyeballs when computer vision can easily detect and track hundreds of 2mm skin lesions over time?

We say the same thing to physios and personal trainers about recording movement in pixels and milliseconds, and some insist they can see/measure and report dysfunction with their eyes, and adequately report it with text.

If Mona Lisa were to be described in words alone, she would have many faces!

The cost of bias, malpractice and delayed intervention will easily outweigh the cost of early diagnosed and early intervention.

In any case, this seems like out of pocket for now. They should be paid a % of saved future costs for early detection, based on historical data IMHO.

Mr. Bilby’s faith in computer algorithms is….touching, as is his faith that screening everyone willy-nilly like this will do anything more than cost more money in downstream confirmatory tests and procedures. It’s not as though we haven’t gone down this road before many times. It is up to the promoters of a new technology like this to show that it does what it says, not to critics to show that it doesn’t, but for some reason it never seems to work out that way. I do like the Mona Lisa analogy, though. It sounds so profound without actually saying anything substantive about the technology. I also note that, if all this does is to take images of skin lesions and track whether they grow over time or not, it’s just a more sophisticated way of doing skin screening exams in a way that more systematically records every lesion on the skin, of which most people have dozens, if not hundreds.

Moreover, there is also already a rather extensive scientific literature on the use of AI to classify skin lesions and carry out skin screenings, particularly for people with darker skin, (Does Neko use recommended best practices for its image acquisition, for example?) for which AI could be particularly useful given the difficulty in identifying and classifying moles as benign versus potentially malignant in darker skin types. However, as this recent review put it, for non-melanoma skin types, AI has “sensitivity and specificity that are not inferior to those of trained dermatologists,” which is hardly a ringing endorsement. Neko Health will have to show that its system is superior to the many existing systems under development and testing. Can it? I sure can’t tell from what I can find out.

Also concerning is this:

What’s perhaps most notable about Neko at this juncture is its aversion to interviews, particularly against the backdrop of high-profile health techs such as Theranos’ spectacular fall from grace after making bold claims with little foundation. Indeed, Neko Health declined to give interviews to international media when it formally launched earlier this year, and little opportunity was given to ask questions ahead of today’s funding announcement.

It is, of course, difficult not to get a Theranos vibe from Neko Health, although the difference here is that, unlike the case with Theranos, where the technology was clearly half-baked and arguably even impossible, the technology clearly exists to produce the devices and tests that Neko Health markets. Indeed, as you will see, other than the “whole body scan,” Neko appears to be doing nothing particularly novel, not even coupling AI with existing technology The main problem is the assumptions behind this raft of tests and the seeming lack of concern about the well-known negatives of screening people for so many measurements at once. The company claims it is doing clinical trials, but searching PubMed failed to find any published results, as did scanning the Neko Health website. I found the latter observation particularly telling, because, if there’s one thing companies marketing a new medical test love, it’s to tout their scientific publications on their websites.

What is Neko Health selling, though?

Neko Health’s “whole body scan”

I noted when I first visited the Neko Health website to see what it says about its whole body scans that the website is incredibly slick but rather lacking in much detail, coupled with language that sounded very much like that used by AmeriScan, the company whose “whole body CT” and screening MRIs had caught my attention back in 2003. Touting its products as “Your health checkup got upgraded, Neko Health brags:

Try the Neko Body Scan, get instant results, and let us monitor your health—so you don’t have to.

Sounds nice, but doesn’t the paternalism of this message conflict with the “take control of your own health” pitch going on elsewhere? And:

Detect. Prevent. Relax. Your body is constantly changing. By measuring, analyzing, and following millions of data points, we create an individually tailored overview of your health.

This is just another form of a favorite advertising buzzword among both conventional physicians and quacks designed to make patients feel special—”individual”—if they use the product being touted. Which use of the “individually tailored” or “personalized” view is being touted here? Let’s take a look.

First, however, let’s see what Neko Health promises with “its own 360-degree full-body 3D scanner integrated with over 70 sensors” (plus, as you will see, a lot of other tests). Neko Health’s Twitter feed touts three main aspects of its products.

First, skin:

How long do you think it will take you to capture every mole on your body? pic.twitter.com/jXskiMjn57

— Neko Health (@NekoHealth) June 20, 2023

I see many punch biopsies in this woman’s future.

Then the cardiovascular system:

How is your heart feeling today? Better health is only a heartbeat away. pic.twitter.com/xw3tGz1p7R

— Neko Health (@NekoHealth) June 28, 2023

And, finally, the scan:

Ahead of your health. The more you understand, the more you can improve how you feel. pic.twitter.com/JmuCrBqmX4

— Neko Health (@NekoHealth) July 3, 2023

The scanner reminds a bit like an over-wide version of the cryogenic tubes featured in Lost in Space in the 1960s:

Read more about our latest financing round here: https://t.co/SXA7ytQy7I

— Neko Health (@NekoHealth) July 5, 2023

And, because I couldn’t resist, here’s what I mean, dedicated to those of you too young to remember the original Lost in Space:

Yes, I grew up on this stuff and so couldn’t resist. Of course, I’m guessing that if they were undergoing Neko Health whole body scans they wouldn’t be wearing 1960s-era tinfoil space suits.

But what, exactly, does Neko Health do at its clinics, in particular its Stockholm clinic that is currently the only location where it has its super-duper-AI-powered whole body scanner? It’s clearly popular. The website brags that all the available appointments are booked and that, if you want one of these whole body scans, you need to get on a waitlist.

First, let’s look at how Neko Health characterizes its whole body scans:

Start with a 360-degree skin scan

Everyone knows it’s important to take care of your skin and regularly check for birthmarks, but seeing a specialist can take months. Neko Body Scan images every centimeter of your skin in less than 20 seconds and tracks every birthmark—so you don’t have to worry.

Full body scan in underwear

Detects birthmarks, rashes and age spots

Follows changes as small as 0.2mm

This is basically a dermatologic skin screening on steroids and AI. While it is true that skin screening is an important modality to detect early cancers, particularly melanoma, one has to wonder how this AI system will do better than the experienced eyes of a dermatologist or melanoma surgeon in detecting suspicious lesions. One way that I could envision such a system having utility would be if it can decrease the number of false negative skin biopsies done on suspicious lesions, but there seems to be nothing on the website even addressing the question. Also, why exclude parts of the body covered by underwear? You can get skin cancer on your buttocks, perineum, and anywhere else covered by underwear.

As I read through Neko Health’s website, I was surprised at how mundane most of it was. For instance, part of the screening involves taking a fasting blood sample for routine labs like a lipid panel and a “full-body blood pressure with 8 non-invasive sensors.” A more detailed description of the tests can be found here, where Neko touts its three clinical trials, which it calls Cardio Alpha, DermaFlow Alpha, and Spectrum 1.

Cardio Alpha is described as a clinical trial “about evaluating the suitability of a novel Laser-Radar-based technology, to assess arterial stiffness and its correlation to cardiovascular risk and diseases” and consists of collecting heart sounds, pulse wave analysis, pulse wave velocity, blood pressure, ECG, and cardiac ultrasound images, none of which is particularly novel or even all that interesting.

Next up, there’s DermaFlow Alpha:

This clinical trial is about evaluating the suitability of multi-modal imaging technology that virtually covers the entire body, to assess the potential of screening and early detection of disease.

The multi-modal technology is based on camera systems, which can capture high-resolution color images (visible spectrum), 3D, and thermal images (infrared spectrum).

By studying the correlation and sensitivity between disease states, gradients, and asymmetries in collected image data, the potential can be evaluated.

Did they say “thermal images”? Holy thermography, Batman! Neko Health is using a fancy, tarted up version of thermography coupled with high resolution images. It’s hard for me not to recall that thermography is an imaging modality that’s long been a favorite of naturopaths, “holistic practitioners,” and other quacks (but I repeat myself), who make extravagant unsupported claims about its ability to detect many diseases, but in particular breast cancer. (Christine Northrup is a big fan, as I first noted in 2010.) To me, this sounds suspiciously like nothing more than an observational study designed to collect a dataset to train Neko’s AI. Recruiting patients to evaluate and test a new technology and train its AI is nothing nefarious in and of itself, but such a mundane goal rather conflicts with all the company’s hype for its products. Do patients who pay for these tests know what they’re signing up for? They expect to be given reassurance (no disease) or to find disease early, the assumption being that finding disease early will result in a better outcome. Do they know that in many cases such tests will trigger further tests and even invasive procedures?

These first two studies are just the buildup to what Neko Health obviously considers its main accomplishment, its “whole body scan.” (I’m surprised that the company didn’t come up with a pithier name for it.) So let’s look at how it describes its Spectrum 1 trial:

Most skin conditions affect and/or are caused by the skin’s microcirculation (blood flow in the smallest vessels). Microcirculation in the skin is also affected by many systemic diseases, such as for example, diabetes and autoimmune diseases.

The disease of large vessels (macro-circulation) can also be caused by basic problems with microcirculation.

Today, there is little opportunity to detect microcirculatory problems early, and it is often discovered when the course of the systemic disease has gone quite far.

This clinical trial will evaluate a trial device that uses a projector to depict patterns on the skin, which the skin absorbs, reflects, and spreads depending on skin composition and structure.

There’s a lot to unpack here. First of all, it is true that many diseases have dermatological manifestations, but certainly by no means do all diseases manifest themselves on the skin in a manner that can be picked up by a system like this. Yet the company makes grandiose claims for this system, which, besides the visual images it records, also measures concentrations of oxyhemoglobin (oxidized hemoglobin) and deoxyhemoglobin (non-oxidized hemoglobin), as well as the “oxygenation within the measured skin area,” to which the wag in me can’t help but say: Congratulations! You’ve reinvented the pulse oximeter as a whole body pulse oximeter! In fairness, the device also measures the concentration of water and melanin in the skin area examined, but in reality it is sounding more and more like a glorified pulse oximeter that measures a few other things.

Again, like the others, this clinical study looks to me like nothing more than a method to gather a training dataset for the company’s AI, which, again, is nothing nefarious in and of itself. What is dubious to me is having your patients fund the research and development of your technology by paying for an unproven test to be part of its AID training dataset. This is the sort of activity that should be funded by the company developing the experimental technology, not patients, but that’s not what appears to be happening. Moreover, the company appears to be enticing patients by making promises, albeit vague ones, about their test being the ultimate in preventive medicine. If that’s not what the company is doing, I have been unable to find any evidence telling me what the specific questions they are asking are.

I was particularly taken by this quote:

Nilsonne said that the company has already proven the resonance of its unique approach to preventative healthcare. Strong demand signals a genuine need and desire for change, which has propelled the company to broaden its horizons and accelerate its growth by forming partnerships with external investors for the first time.

This is nothing more than an appeal to popularity. All it says is that Neko Health’s marketing of its as yet unproven device has been effective.

“Whole body scans” as functional medicine?

Having perused the company website and as much as I could find with Google and PubMed, I was left…dissatisfied. I understand a company wanting to protect its proprietary intellectual property, but the vagueness of the claims was frustrating, especially coupled with the lack of detail about what, exactly, Neko Health’s scans will actually be used for other than a generic “health screening” that will somehow revolutionize preventative medicine. I was interested in learning the identities of the physicians running the clinical development of this technology, because screening asymptomatic populations for occult disease in the hopes that early intervention will result in better outcomes is an area of medicine that is highly complex and fraught with pitfalls, such what to do with “incidentalomas” (lesions or abnormalities found incidentally on a test that a patient is undergoing to look for something else, but more importantly the problem of overdiagnosis, lead time bias, and length bias. Yet, under the “leadership” and “transparency” section of Neko Heath’s website, all I could find were the identities of the founders of the company and its systems for safety, documentation, and quality improvement, which apparently are in accordance with Swedish law. Its press kit was no more informative, consisting mainly of photos of its device.

As the late Dr. Harriet Hall, who was a family physician who served as a flight surgeon in the Air Force, pointed out well over a decade ago, even the yearly physical examination with routine bloodwork is a medical screening tool that has come into question given its low yield in most healthy, asymptomatic patients who have no symptoms or signs of disease and are not a high risk of certain specific diseases.

She also noted:

We are increasingly questioning screening tests that were formerly recommended. The annual chest x-ray, tine test, and urinalysis are long gone. The recommended age limits for mammography have changed. Routine PSA testing is being discouraged. A recent study suggested that a woman whose DEXA scan shows normal bone density or mild osteopenia need not be rescreened for 15 years.

We don’t need to examine all the published literature on screening tests, because the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) has done all the work for us. They continually update recommended screening tests for different age and risk groups based on the latest studies. There are other organizations in the US and elsewhere that make similar recommendations but that may differ to some degree in different countries. In general, a specialty organization is likely to recommend more screening in its particular area of interest, based on a different focus in interpreting the same published evidence. The American Academy of Family Physicians, with a broader perspective, generally follows USPSTF recommendations.

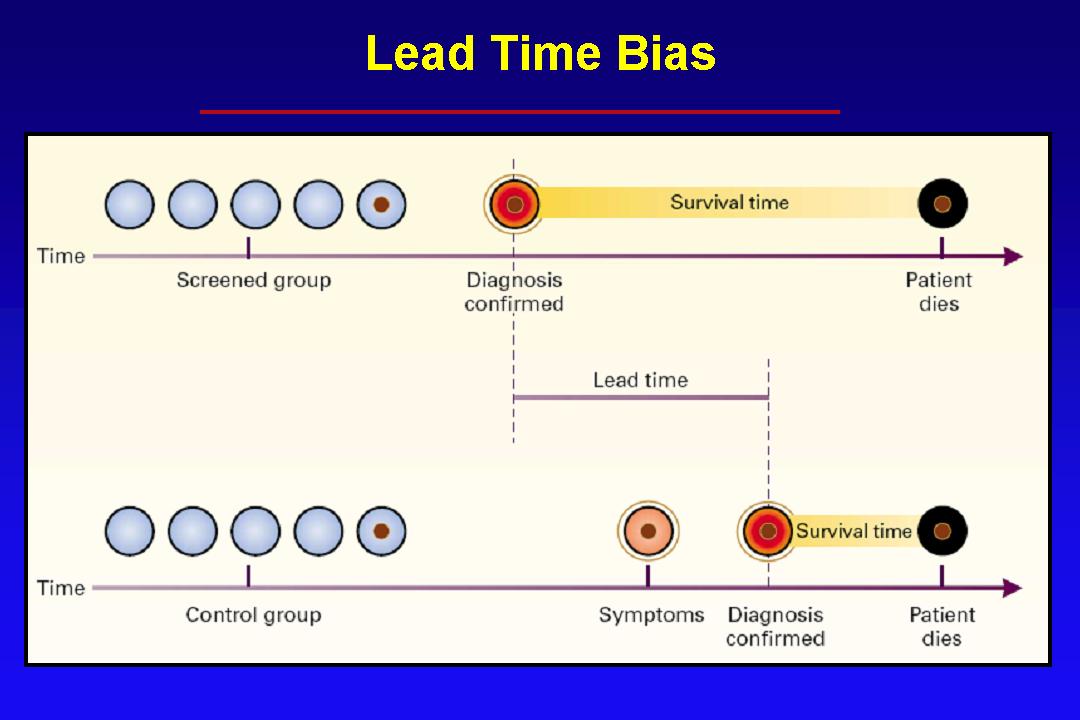

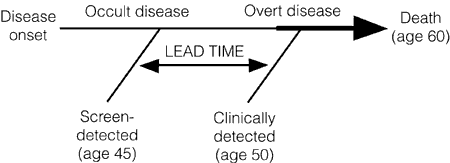

Any new screening test needs to be viewed very skeptically in the light of these observations. For some reasons why, feel free to review some of my articles that discuss the issues involved with any screening test. I discussed mainly screening tests for cancer, like mammography for breast cancer, PSA for prostate cancer, and thyroid ultrasound for thyroid cancer, all of which can artificially inflate survival statistics for cancer, but all involved problems of overdiagnosis, lead time bias, and length bias. (It’s not just these cancers, either.) In fact, let me cite a couple of graphs that I always like to cite whenever the topic of screening comes up. First, here’s an illustration of lead time bias:

Lead time is basically the time between when a screening test detects asymptomatic disease and when the disease becomes symptomatic. Basically, lead time bias can mean that even an ineffective treatment will produce the illusion of prolonged survival when employed against screening-detected disease. Unless intervening to treat occult disease lengthens survival significantly more than the lead time, it is probably not impacting survival.

Here’s another illustration of the concept that I like to cite. Note that lead-time bias is a factor in screening for any disease that can result in death, not just cancer:

As a result of lead time bias, it’s very easy for screening to make it look as though patients are doing better after early detection of their disease, whether they are, in fact, doing better or not. One of the best explanations of the concept of lead time bias that I’ve ever encountered can be found here.

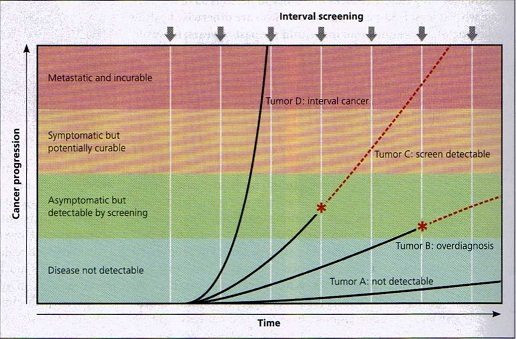

The other factor most relevant to cancer screening is overdiagnosis and length bias illustrated here with the concept of overdiagnosis:

The above graph demonstrates how screening favors the diagnosis of relatively slowly growing cancers, known as length bias. Fast growing cancers, like Tumor D, grow so fast that they become symptomatic or detectable on physical examination between screenings. As a breast surgeon, I see this occasionally, the woman who laments that she gets her mammograms regularly but felt a lump 6 months after her last mammography that turned out to be cancer. This graph also illustrates the problem of overdiagnosis that also results from length bias, as Tumor B is what happens when a slow growing cancer reaches the stage of being detectable by a screening test but is so slow growing that the patient will die of other causes before it causes any problems. Also, remember that this whole discussion only applies to patients who have no symptoms or physical findings. If the patient has symptoms or physical findings, then the test is no longer a screening test but a diagnostic test. If you have symptoms or physical findings that are worrisome for serious disease, you should always see your doctor to have them checked out.

None of this is to say that screening tests are useless, don’t save lives, or at the very least allow less invasive and radical treatments to succeed. Several are not. However, what these entrepreneurs selling new unfocused screening tests for even healthy people always seem not to understand (or even be much concerned about) is that screening for any disease involves a difficult balancing act between disease biology and natural history versus any benefits of intervening in the disease process in its asymptomatic phase. Remember, overdiagnosis is not a false positive, although that is a frequent misunderstanding of the concept. For example, breast cancers and prostate cancers overdiagnosed by mammography and PSA, respectively, are real cancers. Upon biopsy, they look like any other cancer under the microscope to the pathologist. Overdiagnosis represents the diagnosis of a real medical disease or condition that progresses so slowly that, if left alone, it would never put the patient’s life at risk or significantly impact the patient’s health but ends up being overtreated because we currently have no reliable tests to differentiate overdiagnosed disease from disease that needs intervention. These issues are why some screening tests (e.g., mammography) make the cut for clinical utility while others (PSA for prostate cancer) are increasingly questioned. It’s also why the indications for screening tests like mammography (e.g., age to begin screening, interval between tests, etc.) undergo continuous reevaluation based on new science.

One Twitter doc noticed the issue right away, this issue is a problem that we have seen in the past many, many times with these sorts of technologies. The only difference nowadays is that tech people think that adding AI will fix the problem; that is, if they ever even bothered to consider this problem at all, which Neko Health appears not to have:

Do investors think no one in medicine ever had the idea of doing imaging to detect cancer? Or more cynically do they think the worried well will just shell out $317 for a low res scan read by a buggy algorithm? Have they considered the enormous liability of missed diagnoses?

— Nick Mark MD (@nickmmark) July 6, 2023

If there’s one area that AI might have utility, it’s in identifying factors that allow us to differentiate between overdiagnosed disease detected by screening and disease that requires treatment. Frustratingly, from what I’ve observed during the last two decades that I’ve been paying attention to these issues, companies like Neko Health never seem particularly interested in attacking this more difficult problem, again, because they lack the necessary domain evidence and. Again, it “just makes sense” to people without the requisite background expertise who might tell them that their misconception that finding things early will always be good is often not true, or, as one Twitter user put it:

They don’t know what they don’t know likely describes Hjalmar Nilsonne and Daniel Ek quite well. It’s a common occurrence whenever tech entrepreneurs venture into healthcare.

Unfortunately, we know from long experience that in some cases screening for disease does more good than harm (e.g., breast cancer, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and others), but more often all these sorts of screening tests do is to trigger additional tests, some invasive, that can result in harm. You need physicians and scientists with the necessary expertise and a proven track record demonstrated by peer-reviewed publications evaluating the sensitivity, specificity, and positive predictive value of screening tests in addition to your AI experts. In fact, you probably need an even rarer breed, the physician or scientist with experience assessing screening tests who also understands AI and AI algorithms.

One commenter nailed it:

I don’t understand how anyone thinks this is going to save money, either. As soon as you shell out $317 for the scan, that’s gonna lead to thousands of dollars of potentially unnecessary appointments, labs, more imaging that doctors will actually trust, and biopsies.

— chelsea 🙂 (@chelseadjones) July 6, 2023

Before I move on, though I have to contradict one thing that Dr. Mark said. If there’s one thing the history of such tests demonstrates, it’s that the worried well will shell out far more than a mere $317 to undergo various iterations of the “whole body scan.” In fact, there is a whole area of pseudomedicine that tells us that: functional medicine, and Neko Health’s whole body scan and other companies adding AI to a very old idea of doing whole body scans reminded me of this

The comparison between functional medicine and its “everything but the kitchen sink” approach to lab tests was driven home when I found this chart on the Neko Health website:

Here’s where Neko Health reminds me of functional medicine. Remember how I characterized functional medicine as “reams of useless tests in one hand, a huge invoice in the other“? That’s because functional medicine takes a very similar approach of doing lots and lots of tests (both standard and nonstandard) and then correcting every abnormality, whether it’s truly an abnormality or not given that all tests have false positives and if you do enough of them you will by random chance alone get a few abnormal test results, and whether it needs to be “corrected” or not. I’m very much getting a functional medicine sort of vibe from Neko Health.

The whole body scan—with AI!—gold rush

I don’t want to pick on just Neko Health though. It’s far from alone in its rush to raise venture capital to fund the development of this sort of product and suite of tests. It appears to be quite the gold rush out there to add AI to the very old (and discredited) practice of offering whole body scans to the healthy worried well as “preventative medicine.” For example, there’s one startup, Ezra, that’s marketing whole body screening MRI scans. The company claims that “its full-body MRI service monitors for possible cancer and more than 500 other conditions in up to 13 organs,” offering “three-year memberships for $5,300 or five-year plans for $7,000. They include annual exams along with a 45-minute follow-up consultation.” Another company, Prenuvo, is backed by Cindy Crawford and offering another AI-fueled whole body MRI scan direct to consumers for a mere $2,499, showing that, yes, the worried well will pay a lot more than $317 for tests more likely to cause them harm than good, although price competition is coming to this industry, with companies like SimonMed Imaging trying to undercut companies like Prenuvo, although its product doesn’t appear to use AI.

Most of these startups are covered pretty credulously by the press, but I have to give credit to Radiology Business for including some serious skepticism about at least one of them, Prenuvo:

However, some are expressing concern that the service could cause more harm than good. Catherine Livingston, MD, a family medicine specialist who served as lead author of a 2016 report recommending against this practice, is one such skeptic.

“There is certainly not enough known about the use of [artificial intelligence] in direct-to-consumer imaging services,” Livingston, an associate professor of family medicine at Oregon Health Sciences University School of Medicine, told the newspaper. “We don’t even know that the benefits outweigh harms for whole body scans in asymptomatic people. Adding in … AI is a Pandora’s box.”

And, from a December story about Prenuvo:

Dr. Matthew Davenport, the vice chair of the American College of Radiology’s Quality and Safety Commission, said that using MRIs to screen the general population is not likely to improve patient health.

“It is a terrible idea,” he said.

Davenport said there’s a big risk with using a scan as sensitive as an MRI of finding abnormalities that are later found to be benign. Screening may make sense for people with a higher risk for disease.

But Davenport said that for the general public, imaging every organ with such a sensitive test “will harm the patients.” Even if the scan itself doesn’t pose much of a risk, he said, more procedures down the line might pose a bigger risk.

“You find all sorts of stuff that would never occur to the patient,” he said. “And you end up triggering workups, biopsies for imaging studies, operations, for findings in the body that would never have any importance for the patient.”

Precisely. This is the aspect of screening healthy people for everything under the sun that the general public doesn’t understand. Unfortunately, neither do the tech bros who think that AI will make everything better. As always, the devil is in the details, and from my perspective it’s profoundly unethical to charge patients large sums of money merely to provide you with another data point in your training dataset for your AI.

None of this phases the tech people running these startups, unfortunately. For example, listen to Andrew Lacy, founder and CEO of Prenuvo:

“The current healthcare system is reactive. For many, health information comes too late, once a disease or condition has progressed, has symptoms, and is more difficult and expensive to treat,” Lacy said in a statement last fall announcing the $70 million fundraising round. “Our series A financing is validation of Prenuvo’s mission to catch conditions before they become crises and transform the healthcare approach as we know it to one that is rooted in proactive health.”

I love how Lacy equates success in raising venture capital with the medical and scientific value of its technology, which it claims to be unique, because all these companies claim that their AI is unique and better than the others. For example, last year Lacy said:

Lacy said Prenuvo uses proprietary software and artificial-intelligence tools invented by Attariwala to make its whole-body scans different from other scans offered in hospitals.

“Most MRI scans rely on anatomical imaging, which simply shows organ structures,” Lacy said. “Core to Prenuvo’s imaging protocols is a heavy reliance on the combination of anatomical imaging together with newer functional imaging techniques, which increases the ability of MRI to accurately discriminate many conditions.”

Prenuvo’s website indicates it charges $1,000 for a torso scan, $1,800 for a head-and-torso scan, and $2,500 for a whole-body scan, and it doesn’t take insurance. The website says the scans are performed by MRI technologists and analyzed by radiologists trained to read Prenuvo scans.

Lacy said that if a scan finds something abnormal, it shows up in a patient’s dashboard — that patient can take the result to their primary-care physician.

My experience is that primary care physicians are not fond of this sort of thing, because they often don’t know what to do with the results of such scans—or at least are unsure—because these tests are prone to discover all sorts of things that might or might not be harmful but then require a workup. Unsurprisingly, like all companies imaging such imaging systems, Prenuvo claims that its technology avoids pitfalls described by because of its special proprietary technology. How does Prenuvo know this?

Prenuvo has not published any studies finding that these scans catch diseases early and improve people’s health. Lacy said Prenuvo is recruiting for a clinical trial.

I’m shocked—shocked!—to find that Prenuvo started selling its test for big bucks first and only now is trying to prove that it works. I’m also shocked—shocked!—that a search of PubMed for the name of the company showed no clinical trials open, although a search for “MRI” and “artificial intelligence” resulted in dozens of hits for clinical trials looking at AI in imaging. Add the term “screening,” and you’ll find a bunch of clinical trials utilizing AI-fueled MRI to screen for specific diseases, such as breast or pancreatic cancer. Add the term “whole body,” and the number drops to basically zero.

Perhaps this is why I found no clinical trials from Prenuvo:

Andrew Lacy, Prenuvo’s founder and chief executive, said his company plans to partner with researchers to further study its model. It has not yet published data but plans to soon in concert with the American Academy of Neurology conference, among other events.

So, not only has Prenuvo not published any clinical trial results, but it seems to have no clinical trials registered with ClinicalTrials.gov. Does anyone want to bet that what Prenuvo plans is just a large case series of all of its customers who have purchased its scans, a study that without controls is highly unlikely to be informative.

While it’s nice that Prenuvo plans to “partner with researchers to further study its model,” my retort is always; The time to partner with researchers to study your model is before you market it to the public, not after. Also note the utter lack of understanding of the potential complications of using such screening tools. At the very least, event thought the gadolinium used as contrast for MRI scans is safe, gadolinium is not without risk. That’s why yearly doses of gadolinium should at least trigger a risk-benefit analysis, something that none of the companies marketing whole body MRI screening using AI appear to have done, just as AmeriScan never bothered to consider the risk-benefit ratio of yearly doses of gadolinium, plus all the other potential unnecessary workup and biopsies, compared to the potential benefits of its yearly screening.

AmeriScan and a number of “whole body CT scans” and “whole body MRI scans” proliferated two decades ago, only to disappear (for the most part) for several years. Unfortunately AI has provided a seemingly reasonable rationale to resurrect these discredited screening modalities in the likely vain hope that AI will somehow eliminate or at least mitigate the problems associated with old-fashioned whole body scans, be they CT, MRI, or Neko Health’s fusion of photography and thermography coupled with cardiovascular scans. Unfortunately, whether AI can succeed in this is very much an open question, but that doesn’t stop these companies from using AI as a marketing buzzword to sell their product before it’s been proven superior (or at least not inferior) to existing diagnostics.

Truly, these companies are the AmeriScan of the 2020s.