Can a protein originally found in jellyfish improve your memory?

According to ubiquitous Prevagen ads,

Our Scientists Say “Yes!”

But, according the Federal Trade Commission (FTC), the state of New York, and consumer groups, what Prevangen’s scientists actually said was “No!” Hence a lawsuit filed last year by the FTC, joined by the New York Attorney General, against Quincy Bioscience (Quincy), the maker of Prevagen, for making false or misleading statements in labeling and advertisements.

The plaintiffs lost in federal district court, a decision that is now on appeal. How the case is ultimately decided could either strengthen the FTC’s hand in pursuing dietary supplement companies with flimsy evidence for their efficacy claims or encourage companies to go data-dredging when their studies don’t yield the desired results.

Oh no! Not another Prevagen ad!

If you are a sentient being with a cable subscription, you’ve no doubt seen advertisements for Prevagen and their claim that:

In clinical trials, Prevagen has been shown to improve short-term memory.

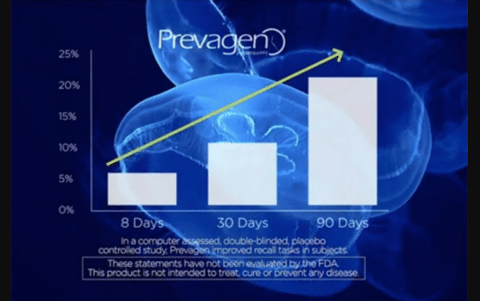

In one version, the results are illustrated with a blue jellyfish-themed chart showing a straight shot to memory improvement in 90 days.

The TV ads are one part of an aggressive marketing campaign which includes a website, social media, radio, print ads, infomercials (“The Better Memory Show”) and a “Prevagen Express” bus that visited health food stores and health expos. By all accounts, the company’s efforts have been wildly successful, with $165 million in total sales. A month’s supply of Prevagen costs between $24 and $68, depending on the formulation and source, and is widely available at retail outlets like CVS, Walgreens and Duane Reed, as well as through online sellers, like Amazon, and healthcare practitioners.

Prevagen is not the only player in the brain supplement business. According to Newsweek:

That often-desperate pursuit of remedies has created a lucrative marketing opportunity, and the supplement industry is cashing in. Products aimed at consumers worried about brain health and memory have contributed to a more than 10-fold increase in the number of supplements marketed in the U.S. over the last two decades.

At the request of Sen. Claire McCaskill, the Government Accountability Office investigated the marketing of brain and memory supplements and issued a report last year. The GAO noted that dietary supplements claiming to improve memory had sales estimated at $643 million in 2015, almost double the 2006 sales. Its report found consumer confusion regarding the roles of the FDA and FTC in regulating memory supplements, which could affect the ability of consumers to make complaints, and suggested better coordination between the two agencies.

Prevagen is a dietary supplement containing a synthetic version of the active ingredient, apoaequorin, a protein. Apoaequorin was originally obtained from a species of jellyfish called Aequorea victoria, which, say scientists, is not nearly as glamorous as its blue-glowing photographs suggest.

Apoaequorin has been shown in laboratory studies to support neuronal cells. Based on in vitro and in vivo animal studies, we hypothesized that apoaequorin has the potential to enhance memory and cognitive function in humans. Previous work with apoaequorin in aged canines demonstrated cognitive enhancement. [Citations omitted.]

And:

In a double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial, Prevagen demonstrated the ability to improve aspects of cognitive function in participants with either normal cognitive aging or very mild impairment, as determined by pre-trial screening.

Well, not exactly, says the FTC, as we’ll see in a moment.

Quincy also claims that Prevagen has undergone “extensive” safety testing and that no adverse effects were recorded when tested at dosage levels much higher than recommended, but does not reveal (except in fuzzy photos of the journal articles) that these were studies in rodents and petri dishes, not humans.

The feds step in

Prevagen caught the eye of regulators as early as 2012, when the FDA sent the company a warning letter stating that Prevagen was both an unproved drug and not legally a dietary supplement. At the time, Prevagen was marketed as a treatment for Alzheimer’s disease and head injury, claims only FDA-approved drugs can make. In addition, the FDA pointed out, apoaequorin is not a “dietary ingredient” as defined by the Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act, so Prevagen could not legally be marketed as a dietary supplement either. The FDA’s inspectors also found that Quincy had reported only two of more than 1,000 adverse events, some requiring hospitalization, and product complaints, including heart arrhythmias, chest pain, vertigo, tremors, seizures, strokes, and worsening of multiple sclerosis.

The current status of the FDA matter is unclear, but since the warning letter, Quincy appears to have stopped explicitly touting Prevagen for diseases, focusing instead on its claim that clinical trials show Prevagen improves memory. It is this claim that put the company in the sights of the FTC and the New York AG.

Last year, the FTC, which had received a number of consumer complaints about Prevagen, and the New York Attorney General, filed suit against Quincy, alleging violations of federal and state consumer protection laws, charging them with making false and unsubstantiated claims that Prevagen improves memory, provides cognitive benefits, and is “clinically shown” to work. According to an FTC spokesperson:

The marketers of Prevagen preyed on the fears of older consumers experiencing age-related memory loss. . . . But one critical thing these marketers forgot is that their claims need to be backed up by real scientific evidence.

The complaint sought a permanent injunction against the allegedly false and misleading claims made by Quincy, refunds for consumers, and “disgorgement of ill-gotten gains,” i.e., turning over profits made from Prevagen.

At the heart of the FTC’s complaint is the Madison Memory Study, paid for and conducted by Quincy, on which the company primarily relies in making claims that Prevagen is “clinically proven” to improve memory. The trial methodology and results have never been peer-reviewed or published in a scientific journal. The only written report available to the public is a “Clinical Trial Synopsis” on the company’s website.

The FTC and Quincy agree that the study was a double-blind, placebo-controlled human clinical study using objective outcome measures of cognitive function. It involved 218 subjects taking either 10 milligrams of Prevagen or a placebo, without a no-treatment group. The subjects were tested on nine computerized cognitive tasks to assess a variety of cognitive skills, including memory and learning, at intervals over 90 days. They also agree that the Madison Memory Study failed to show a statistically significant improvement in the treatment group over the placebo group on any of the nine cognitive tasks.

Unsurprisingly, to the FTC this means, contrary to advertisements, the “double-blinded, placebo controlled trial” of Prevagen did not “demonstrate the ability to improve aspects of cognitive function.” Thus, the FTC charges: (1) there is not “competent and reliable scientific evidence” to support Prevagen’s claims, which is required of health care product advertising, and (2) the claim that Prevagen is “clinically proven” is false.

Not so fast, says Quincy. That’s because, after failing to find a treatment effect for their study population as a whole, their researchers conducted more than 30 post hoc analyses of the results, looking at data broken down by several variations of smaller subgroups for each of the nine cognitive tasks. And here they found that older treatment subgroups having low to mild initial impairment had modest levels of improvement in three of the nine cognitive tasks.

In other words, Quincy went p-hacking, and those results, they say, are sufficient to support their advertising claims.

The FTC disagrees, stating in its complaint:

This methodology greatly increases the probability that some statistically significant differences would occur by chance alone. Even so, the vast majority of these post hoc comparisons failed to show statistical significance between the treatment and placebo groups. Given the sheer number of comparisons run and the fact that they were post hoc, the few positive findings on isolated tasks for small subgroups of the study population do not provide reliable evidence of a treatment effect.

The FTC points to the blue jellyfish-themed chart, reprinted in color in the complaint, as an example of how Quincy Bioscience is fudging with the Madison Memory Study results:

It indicates that a “double blinded, placebo controlled study” showed dramatic improvement in recall tasks when, in fact, the results for the specific task referenced in the chart showed no statistically significant improvement in subjects taking Prevagen compared to subjects taking a placebo. In addition, Defendants eliminated from the chart one of the four data points in the study – day 60. At day 60, the recall task scores of subjects taking Prevagen declined from day 30, and were slightly worse than the recall task scores of subjects in the placebo group.

The FTC also takes issue with Quincy’s assertion that apoaequorin is capable of crossing the blood-brain barrier, which, according to the FTC, is essential to their claim that their product improves memory and cognition. They don’t have evidence for this, according to the complaint, and, in fact, their own safety studies show that the protein is rapidly digested in the stomach and broken down into amino acids and small peptides, like other dietary proteins.

Prevagen defends its position in a brief filed with the appellate court as appropriate and common in the dietary supplement industry. In any event, it says, there is no law requiring the level of substantiation for healthcare product claims the FTC complains it failed to meet. Rather, the FTC itself has said it will take a flexible approach to substantiation, including the acceptance of less than “gold-standard” RCT studies.

It also argues, somewhat disingenuously, that it never said apoaequorin was capable of crossing the human blood-brain barrier. Rather, based on its canine studies, its:

marketing statement thus included only an indication “that apoaequorin is capable of crossing the blood brain barrier…in dog[s.]”

Of course, unless consumers were contemplating giving Prevagen to their dogs, this wouldn’t be relevant, unless one assumes this information was included so consumers would, by implication, conclude that apoaequorin can get into their brains as well. As the FTC says:

The first step in evaluating the truthfulness and accuracy of [dietary supplement] advertising is to identify all express and implied claims an ad conveys to consumers. Advertisers must make sure that whatever they say expressly in an ad is accurate. Often, however, an ad conveys other claims beyond those expressly stated. Under FTC law, an advertiser is equally responsible for the accuracy of claims suggested or implied by the ad. Advertisers cannot suggest claims that they could not make directly.

Ongoing litigation

Quincy successfully moved to dismiss the complaint for failure to state a claim. The district court ruled that the FTC, in its allegation that the post hoc analyses were insufficient to support Prevagen’s efficacy claims:

fails to do more than point to possible sources of error but cannot allege that any actual errors occurred.

As to the FTC’s claim that apoaequorin is rapidly digested and broken down into amino acids and small peptides like any other dietary protein, the court said:

This point, contradicted by canine studies whose relevance plaintiffs challenge, loses force when applied to the results of the subgroup study which make it clear that something caused a statistically significant difference between those subjects who took Prevagen and those given a placebo.

From the Wikimedia Commons, originally posted by Flickr user Alex E. Proimos (link)

That, of course, was the whole point of the FTC’s first argument: post-hoc data-dredging is unreliable and can’t rule out “statistically significant difference” as mere noise.

On appeal, there is a substantial argument over whether a ruling on these issues was appropriate on a motion to dismiss, where the only question should be whether the allegations of the complaint are sufficient to state a claim against the defendants. Motions to dismiss are decided at the very earliest stages of a trial and only the plaintiffs’ complaint and defendants’ answer are under consideration. Courts are not supposed to consider any evidence or rule on questions of fact, two errors that the FTC says the district court made in this case. Whatever the merits of the case, I think that the complaint should not have been dismissed, and at least one commenter, also not a party to the litigation, agrees that the Second Circuit Court of Appeals is likely to reverse on this issue, giving the parties an opportunity to more fully flesh out the evidence and their arguments.

Joining, as amici curiae (“friends of the court”), the FTC and the state of New York in arguing the district court’s decision should be overturned is an impressive array of consumer groups and academics: Truth in Advertising, Inc., AARP, Advertising Law Academics, National Consumers League (their collective brief is here), Public Citizen, Center for Science in the Public Interest, and the Collaboration for Research Integrity and Transparency (collective brief here).

I had not heard of the Collaboration for Research Integrity and Transparency and found its mission interesting, and worthy:

The Collaboration for Research Integrity and Transparency (CRIT) is a multidisciplinary initiative of Yale Law School, Yale Medical School, and Yale School of Public Health. CRIT’s mission is to promote public health by improving the transparency and integrity of biomedical and clinical data. CRIT’s scientists have conducted research showing that data transparency and integrity are crucial to the accurate and informed use of drugs, devices, and biologics. Through litigation and policy work, CRIT focuses on enforcement of statutes and rules governing the accurate reporting of clinical trial results.

The latter amici curiae group explains in its brief why post-hoc analyses of data like that used by Quincy is not reliable. In part, they say:

Because the experts in the field of medical research would not generally accept Quincy’s post hoc subgroup analyses as yielding scientifically sound and reliable results, the FTC has adequately alleged that the analyses do not substantiate the claims and properly stated a claim on which relief can be granted. Subgroup analysis refers to an evaluation of study results in a subgroup of the subjects defined by certain baseline characteristics. See Rui Wang, et al., Statistics in Medicine – Reporting of Subgroup Analyses in Clinical Trials, 357 New Eng. J. of Med. 2189 (2007). Subgroup analyses are post hoc when the subgroup levels and “the hypotheses being tested are not specified before any examination of the data.” Id. at 2190. Post hoc subgroup analyses have long been viewed with skepticism by research scientists and statisticians. See, e.g., Andrew Oxman, et al., A Consumer’s Guide to Subgroup Analyses, 116 Annals of Internal Medicine 78, 83 (1992) (stating that “there are those who ignore scientific principles in the subgroup analyses they undertake and report, go on fishing expeditions, and indulge in data-dredging exercises” and that subgroup analyses showing small, marginally significant interactions generated by post hoc exploration of a single dataset “should be viewed with great skepticism”).

As another commenter pointed out, the FDA prohibits post-hoc subgroup analyses for efficacy claims in clinical drug trials, and explains why:

The FDA is concerned both about conflicts of interest and that performing multiple subgroup analyses can increase the risk of false-positive findings. In other words, the more analyses one conducts, the more likely it is that one will find a false positive result because when groups get smaller, confidence intervals grow larger and statistical power is reduced.

If the district court’s dismissal is overturned and the case remanded for further proceedings on the merits, the FTC will be able to present this scientific consensus to the court as evidence. (Even if it isn’t, the FTC and the New York AG remain free to file an amended complaint addressing the errors the district court in their pleadings.)

As well, if the case returns to the district court, the plaintiffs/appellants will be in good company in arguing the blood-brain barrier issue. Here’s what experts have said about that:

Meanwhile, Quincy’s claims are rejected by the research community, which notes that any protein taken by mouth will be broken down into amino acids in the stomach and won’t reach the brain in its original form.

Quincy’s claims “have no legitimate reality based on the real facts of science, nutrition and memory,” says David Mead, a molecular biologist and cofounder of Varigen Biosciences in Madison.

“It’s quackery. I can’t think of anything better to say,” says Baron Chanda, an associate professor in the UW-Madison Department of Neuroscience.

“I second the ‘quackery,'” says Chanda’s neuroscience colleague, professor Edwin Chapman. “This is downright silly — no other word for it.”

And:

“It is biologically inconceivable that taking a protein by mouth would have any effect on memory,” [Dr. David S.] Seres, [director of medical nutrition at Columbia University Medical Center] concluded.

For a longer, wonkier explanation of why apoaequorin is highly unlikely to cross the blood-brain barrier, see this Medscape article.

The importance of this case to the dietary supplement industry is evidenced by the fact that several industry trade groups have joined Quincy as amici curiae: Council for Responsible Nutrition, Consumer Healthcare Products Association, Natural Products Association, and the Alliance for Natural Health – USA.

My guess is that the lower court’s decision will be reversed and the case will go back to the district court, where this case will become another in the long history of expensive and time-consuming litigation over dietary supplements, much of which could be avoided if Congress ditched DSHEA and passed a law regulating dietary supplements and their marketing meant to protect consumers, not the industry. Here’s another prediction: that’s not going to happen.