Introduction: The harms we cause, the harms we fail to prevent

Death from COVID-19 is worse than myocarditis from the vaccine. Though this seems like an uncontroversial statement, intelligent doctors from prestigious universities have penned articles opining that it is preferable to leave young people vulnerable to the virus. While some doctors are clearly motivated by reflexive contrarianism and the media appearances that brings, I suspect that this viewpoint is partially explained by a quirk in how we perceive risk, specifically our tendency to view risks of omission differently from risks of commission. Put another way, we regret harms we actively cause more than those we passively fail to prevent.

The trolley problem

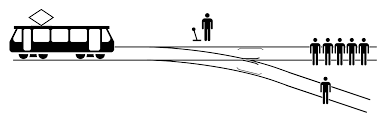

The choice to vaccinate young people against COVID-19 can be likened to the trolley problem. In this famous thought experiment, a trolley is about to kill five people. By pulling a lever, the trolley will be diverted, and just one person will die. Would you pull the lever?

Recognizing that a simple tug on a lever can save four lives, most people say they would pull it. However, a subtle twist can change people’s response. Consider the following:

As before, a trolley is hurtling down a track towards five people. You are on a bridge under which it will pass, and you can stop it by putting something very heavy in front of it. As it happens, there is a very heavy man next to you – your only way to stop the trolley is to push him over the bridge and onto the track, killing him to save five. Should you proceed?

In contrast to the original scenario, many people will reject pushing the heavy man. Yet other than feeling more responsible for the heavy man’s death, nothing has really changed. Multiple variations of the trolley problem exist, and they demonstrate that people feel differently about a bad outcome depending on whether they believe they caused the calamity or whether they merely failed to prevent it.

Moreover, people’s behavior depends on what they perceive the status quo to be, as this determines whether or not they perceive themselves to be taking an action. For example, people are more likely to save for retirement or be an organ donor when they have to opt out of doing so, rather than opting in. With regards to the trolley problem, while some people would be unwilling to push the heavy man on to the train tracks, they might also be unwilling to rescue him if he were in the process falling onto the tracks, as rescuing him would condemn five other people to death.

Medicine and the trolley problem

The practice of medicine is analogous to the trolley problem in that clinicians often must choose between harms they might directly cause versus harms they might fail to prevent. When a treatment harms a patient, clinicians naturally feel responsible, even if the treatment was appropriate. The desire to avoid harming patients at all costs is captured in the dictum “First, do no harm”. Taken to its extreme this would preclude any medication, surgery, or diagnostic test. Conversely, when a disease harms a patient, clinicians feel sympathy, but they are unlikely to feel personally responsible. This serves as a powerful motivation to avoid harming patients through action, even if inaction is more likely to result in substantial harm. Studies have provided evidence of the Omission Bias in doctors. In one study, pulmonary and critical care doctors were given scenarios involving the evaluation of pulmonary embolism and treatment of septic shock, two potentially fatal conditions. When an omission option was available, a majority of respondents chose a suboptimal treatment strategy.

Of course, a patient who is harmed by their illness may suffer more than a patient who is injured by a treatment. Though suffering from an illness is not necessarily reduced because it is “natural”, it is often perceived this way. In one study, many people refused a vaccine or medication against influenza due to potential side effects, even when it lowered the overall risk of a poor outcome. In contrast, many people were willing to accept a treatment as long as it was called a “natural herb”, even when the risks and benefits were identical to a treatment synthesized in a laboratory. The Omission and Naturalness Biases are driving factors behind anti-vaccine sentiments.

Currently, vaccinating young people feels like doing something and not vaccinating them feels like doing nothing. Moreover, the harms of vaccination, while uncommon, are highly visible, while the benefits to any individual are often invisible. For these reasons, the risks of vaccinating are often perceived as greater or unwarranted compared to the risks of not vaccinating. When a young person develops myocarditis after a vaccine, clinicians may feel responsible. In contrast, when a young person is harmed by the virus, individual clinicians will not feel culpable, even if the person dies from the virus. The harms of vaccination feel intentional, like someone stealing $20 from you. The harms of the virus feel accidental, like having $20 fall out of your wallet. Similarly, vaccine mandates for COVID-19 are perceived as a deviation from the status quo. Therefore, they have generated opposition from some doctors who previously voiced no concern over vaccine mandates other diseases like polio and measles. These mandates have existed for decades and are a routine part of life, and they were previously opposed by only the most dedicated anti-vaccine advocates.

According the CDC’s COVID Data Tracker, 650 children and 3,643 adults age 18-29 have died of COVID-19 in the USA. The American Academy of Pediatrics has added 185 deaths to its tally since July 1st, including many teenagers who were old enough to receive the vaccine. After hundreds of millions, perhaps billions of doses, I am aware of eight possible deaths from the mRNA vaccines (here, here, here, and here) in the entire world and even these were mostly, if not exclusively, in adults. Though I’ve consistently argued that vaccine-myocarditis should not be trivialized, the virus is clearly more dangerous than the vaccine. Seat belts too can severely harm people, though these injuries are rightly considered mild compared to the injuries they prevent. As with seat belts, there is no rational reason to treat harms caused by the vaccine as categorically worse than harms caused by the virus.

Letting a child ride in a car without a seatbelt is doing something. Even though it might not feel that way, not vaccinating young people is also doing something; it is leaving them vulnerable to a dangerous virus. These harms are not just theoretical. Tragically, young people have died or needed mechanical ventilation in the ICU after declining the vaccine for fears of side effects. A recent study by the CDC found that unvaccinated children are hospitalized 10 times more often than vaccinated ones. As such, vaccines fit perfectly with the dictum “First do no harm”. Framing it this way takes the spotlight off the clinician and puts it where it belongs, on the patient. Clinicians must take care not to let their desire to appear blameless take precedence over what is actually best for patients. For this reason, I would pull the lever, steering young people away from the virus and towards vaccination, even though some will develop myocarditis. To others, however, the situation is more analogous to pushing a large man onto the train tracks. Lives would be saved, but at an unacceptable cost; they would feel responsible for those who were hurt by the vaccine.

Another thought experiment

With this in mind, I propose a thought experiment of my own.

Imagine that all children are born with perfect immunity to COVID-19, though this gift comes with a cost. About 1 in 8,000 boys will develop myocarditis when they hit puberty. This hospitalizes them for 2-3 days, however essentially all affected boys recover fully with simple treatments. They are advised to abstain from vigorous activity for several months and will have to be monitored over the long-term.

An enterprising doctor develops a medication that prevents this myocarditis, but negates children’s immunity to COVID-19. While the vast majority of children who take this medication will be fine, overall, young people who contract COVID-19 will be hospitalized at a higher rate than they were previously. Some will be very sick, needing ICU-level care and mechanical ventilation. Others will get long-COVID and feel sick for weeks or months. Those who take this medication are now at risk for viral myocarditis from the virus, and this will be life-threatening for some of them. If this medication is given to many millions of American children, thousands will get MIS-C, which is associated with more severe cardiac outcomes. Hundreds of children will die of COVID-19.

Not vaccinating young people leads to the same grave harms as using this hypothetical medication. If you wouldn’t give young people this medication on the principle of “First do no harm”, then you should be in favor of vaccinating them against COVID-19.