One of the features of the current pandemic leading to anxiety is that this is a new virus and a new disease, and so we don’t yet know what the full clinical picture of COVID-19 is. We are learning the most common clinical features (fever, chills, cough, loss of taste or smell), the asymptomatic rate, and the case fatality rate, but it will take time and more research to fully understand this disease and this virus.

It especially takes time to learn the less common features of a disease like COVID-19. One recent report illustrates this – a case series of five patients in a NYC health system presenting with young stroke (<55). Such reports are often how new medical knowledge is first acquired – a clinical observation of something out of the ordinary. These observations are critical, but are never the final word. They essentially represent a hypothesis that needs to be tested. Let’s review the report and then put it into this context.

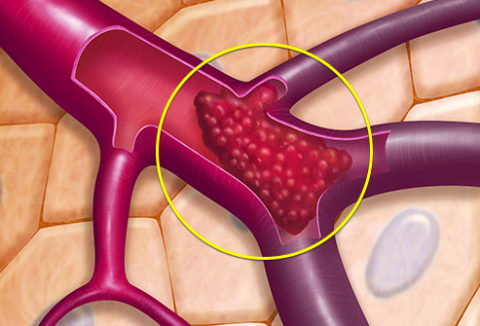

The authors report five cases of large vessel stroke in patients with confirmed COVID-19 all younger than 50, and therefore classified as a young stroke. Strokes in those younger than 50 are relatively rare, and so always attract clinical attention. In other words, they don’t just happen as a consequence of aging (atherosclerosis, chronic hypertension, etc.). Neurologists will do an extended workup looking for an underlying cause (referred to as a “young stroke workup”). A young stroke, for example, may be due to an underlying inflammatory disease, or blood disorder leading to an increased tendency for the blood to clot (hypercoagulopathy). Trauma to a large vessel is also a possibility – a small tear in a vessel can occur even from a seemingly mild trauma.

There is circumstantial evidence that these five strokes (or at least many of them) may be causally related to COVID-19. First, they all were confirmed to have the disease. Also, they all had the same type of stroke – large vessel stroke caused by a blood clot (thrombus). That is at least consistent with a common underlying mechanism.

The authors report that:

By comparison, every 2 weeks over the previous 12 months, our service has treated, on average, 0.73 patients younger than 50 years of age with large-vessel stroke.

So that means over the two-week period reported there were an excess of about 4 young strokes. One of the five cases reported had a history of stroke, so perhaps that was the baseline stroke, but it is also possible that stroke was precipitated by COVID-19. Statistically this bump in cases is significant, and certainly deserves attention. One possibility is that COVID-19 can cause a hypercoagulable state in some patients with the disease, increasing the risk of blood clotting events like stroke. If this is true then we would also expect an increase in other clotting disorders, like heart attacks, pulmonary embolism, and deep vein thrombosis (DVT).

The authors also report:

A retrospective study of data from the Covid-19 outbreak in Wuhan, China, showed that the incidence of stroke among hospitalized patients with Covid-19 was approximately 5%; the youngest patient in that series was 55 years of age. Moreover, large-vessel stroke was reported in association with the 2004 SARS-CoV-1 outbreak in Singapore.

It’s hard to know what to make of that data without further information. So there are still significant unknowns here.

First, it is possible that these five cases are a statistical fluke. Medical experts are trained to notice statistical outliers, and organizations like the CDC track such outliers to see if there is an underlying cause. We call such outliers “clusters” and they are often reported and investigated. It is common, however, for such clusters to be nothing but statistical flukes. If you think of all the diseases in all the clinical settings, cities, and regions around the country and world, we should expect statistical clusters to occur by random chance alone. Epidemiologists can evaluate such clusters statistically to determine the likelihood that they are random or real.

In essence the medical system is mining the large set of data represented by medical cases, and will see plenty of illusory or statistical patterns that are random, but can look impressive in isolation. The ultimate test is looking at new data going forward. If the cluster is real then we would expect the trend to continue, for new excess cases to occur. One pitfall in doing follow up studies, however, is including the original data. If the original cluster was a fluke, including those original cases in later data will contaminate that data and perpetuate the fluke. For this reason follow up studies should look at only fresh data.

There is also the possibility of confirmation bias. Once you have a hypothesis, there is the tendency to look for data to confirm the hypothesis. This might mean looking in places or in ways that have not been done before, and then assuming that what is found is new (rather than just the method of looking being new). Apparent clusters can also be due to shifting definitions and diagnostic criteria, or to new diagnostic technology or standards.

If the cluster was a statistical outlier, then we would expect regression to the mean – cases would return to a more likely statistical background. Comparisons can be made to fresh data in other locations, to future sets of data, or to different subpopulations.

With regard to large vessel stroke in COVID-19 patients, do we see the same cluster in other locations? What about other age groups – why would younger patients be affected but not older ones? Is it just that strokes are more common in older patients and therefore do not garner as much attention? An excess of five older strokes might be lost in the background.

If this is a true cluster, and there is a confirmed correlation with COVID-19, what is the exact mechanism? Hypercoagulability is likely, and not uncommon in inflammatory illnesses, so a cause is plausible. If so, are there any treatments that can mitigate this increased risk? At the very least patients with COVID-19 should be on the lookout for any symptoms of early stroke, and present immediately to medical attention if they have any. Some of the patients in the case series delayed presentation to the ER because of the pandemic.

This is all one tiny facet of this new and complex disease, and will require extensive clinical research and time to fully understand. Others less common but significant features may also emerge as the pandemic unfolds.