If there are certain titles and sentences that I never expected to use for a blog post and certain sentences that I never, ever expected to write as part of a blog post, near the very top of the list has to be anything resembling “John Ioannidis uses the Kardashian Index to attack critics of the Great Barrington Declaration”. Has to be. It’s a sentence and title so off-the-wall that, even in the most fevered flight of ideas that sometimes run through my fragile eggshell mind as I contemplate what I’m about to write in this and my personal blog, I could never have strung these words and thoughts together unaided unless I had actually seen John Ioannidis publish a paper in which he did, indeed, weaponize the Kardashian Index in order to attack the signatories of the John Snow Memorandum, which, to my utter disbelief, really happened last week in the form of a paper authored by John Ioannidis and no one else published in BMJ Open Access titled ‘Citation impact and social media visibility of Great Barrington and John Snow signatories for COVID-19 strategy“.

I’ll stop right here for a second to reassure readers that I fully realize that those who don’t know who John Ioannidis is and are not familiar with the Great Barrington Declaration (GBD), the John Snow Memorandum (JSM), or, for that matter, the Kardashian Index (K-index) are very likely scratching their heads right now wondering whether Gorski has gotten a little too much into the single malt scotch. That is entirely understandable, but I assure you that I was stone cold sober when I wrote this. (Actually, I have to wonder if Ioannidis was sober when he wrote his paper!) However, because of the bizarreness of the paper that I’m about to discuss, before I delve into it I will now take a moment to try bring everyone up to speed, so that you can all understand why the paper is a combination of bonkers and awful, not to mention a continuation of Ioannidis’ ongoing assault on science communicators with a significant social media presence who have criticized him. Regular readers, however, will likely be familiar with at least two things, though. First, we here at Science-Based Medicine have written a fair amount about the GBD and John Ioannidis. Some might even be familiar with the John Snow Memorandum, a response by public health scientists to the GBD. As for the Kardashian index, that seems to have started as a joke, leading me to wonder why someone like John Ioannidis would take it seriously enough to write a paper like this about it. In any event, before I get to the paper, here’s some relevant background. If you’re familiar with this, feel free to skim or skip the next couple of sections, but I think that it will still be worthwhile for even those familiar with all these terms and the background to review them, because doing so will really help put this paper into context.

John Ioannidis versus science communicators

As I alluded to above, John Ioannidis has for a while been more or less at war with science communicators who have criticized him. Of course, given his reputation and his pivot to questionable takes on COVID-19, he is a huge target. How did we get here? First, part of the reason Ioannidis is such a huge target is because he is a physician-scientist at Stanford University—Professor of Medicine and Epidemiology and Population Health—who is also one of the most published scientists in the world (if not the most published living scientist), with well over 1,000 peer-reviewed papers indexed in PubMed as of yesterday and eleven papers already in 2022. (By comparison, I have one co-authored paper in 2022 thus far, and that’s just because it took longer to be published than expected, pushing its publication date to a week ago.) As I’ve said many times, John Ioannidis was at one time a personal scientific hero and, I daresay, a hero of SBM bloggers in general. Pre-pandemic, we featured general laudatory commentary about a number of his papers, including papers about bad epidemiology regarding diet and cancer risk, the life cycle of translational research, whether popularity leads to unreliability in science, problems with reproducibility in science, and the reliability of scientific findings, all of which contributes to the puzzlement many of us at SBM have expressed over Ioannidis’ evolution into a COVID-19 contrarian who has been wrong about so much about the pandemic and has even credulously regurgitated outright conspiracy theories about it. Maybe, however, this development should not have been such a surprise. Let’s see why.

Ioannidis is most famous for having written the 2005 paper “Why Most Published Research Findings Are False“, which investigated why so much of what is published in the biomedical literature later turns out to be incorrect. It is, of course, a paper whose findings have been endlessly misused by cranks, quacks, antivaxxers, science deniers, and conspiracy theorists to claim that most science is false or “at best a coin flip’s worth of certainty” (and therefore their pseudoscience and quackery should be taken seriously as being correct), but that doesn’t mean it wasn’t a worthwhile endeavor. Those of us who support science- and evidence-based medicine recognized it as simply trying to quantify something that we had long intuitively known, namely that one should never take any single paper as the be-all and end-all, that we should base our medicine on a confluence of mutually supporting evidence, because the initial papers published on a topic, the “bleeding edge” sorts of papers if you will, often are later shown to be mistaken. Indeed, there’s even now a term for it, the “decline effect,” or, as I like to call it, science correcting itself, even if the process is often messy and slow.

Even pre-pandemic, though, I found myself not as enthusiastic about several of Ioannidis’ takes on issues. The first time I found myself seriously at odds with an Ioannidis study was in 2012, when he tried to argue (badly) that the NIH funding crisis is completely broken and favors “conformity” and “mediocrity”. If you want the full explanation, read this and, for background, this, but the CliffsNotes version is simple. He operated from the unproven assumption that funding more “risky” research would lead to more scientific breakthroughs and also assumed that publication indices are the be-all and end-all of scientific importance. (This is a recurring theme throughout his career that has contributed to his COVID-19 issues.) Consistent with this sort of disagreement, I also thought that Ioannidis exaggerated when he claimed there was a “reproducibility crisis” in biomedical science, although my disagreement wasn’t as sharp as it was about Ioannidis’ apparent dismissal of the NIH funding process as being a bunch of sheep rewarding only “safe” scientific proposals with funding. Then there was the time when Ioannidis argued that evidence-based medicine (EBM) was being “hijacked” by industry while totally ignoring how pseudoscientific “integrative medicine” and “complementary and alternative medicine” (CAM) had taken advantage of the huge blind spot of EBM with respect to scientific plausibility to “integrate” quackery with medicine.

Then came the COVID-19 pandemic.

Since the pandemic hit, Ioannidis has arguably been one of the most prolific producers in the scientific literature of articles that downplay the severity of the pandemic, many based on methodolatry. Examples abound and have been documented mainly by Jonathan Howard and myself, the most egregious example being when Ioannidis credulously repeated a conspiracy theory from early in the pandemic claiming that doctors were intubating COVID-19 patients willy-nilly who didn’t really need intubation, thereby killing them. Less egregious (but still quite egregious) examples include downplaying the death toll from the pandemic by misrepresenting how death certificates are filled out to claim that it was comorbidities killing patients rather than COVID-19 and that COVID-19 mortality statistics were therefore hugely exaggerated (another conspiracy theory); downplaying the impact of the pandemic on hospitals; and publishing articles that overestimated the prevalence of COVID-19 and underestimated its infection fatality rate (IFR), among other things.

As Ioannidis started to receive something he wasn’t used to, namely large amounts of harsh (and, to my mind, justified) criticism for his conclusions, he started firing back with scientific papers that indulged in what can only be described as ad hominem attacks. For example, in one paper he indulged in the most gratuitous ad hominem attack I’ve ever seen in a scientific paper against a graduate student named Gideon Meyerowitz-Katz, who had published an article that found an IFR far higher than Ioannidis had estimated. More recently, I discussed Ioannidis in the context of the Carl Sagan effect, in which scientists who take the time to engage with the public to communicate science tend to be viewed by many of their peers as inferior scientists, based on a stunningly lazy exercise in bibliometrics in which Ioannidis concluded that science communicators who are interviewed in the media are not, by and large, members of the top 2% of scientists in terms of bibliometric metrics. It was as big a “Well, duh!” conclusion as I’ve ever seen, given that there’s no evidence that effective science communication correlates with the publication metrics that Ioannidis used and served more as yet another attack on his critics on social media than anything else.

This latest paper by Ioannidis takes his lashing out at critics to the next level, but to understand why and how, you need to understand the conflict between the GBD and the John Snow Memorandum and why it is not surprising that Ioannidis has clearly allied himself with the signatories of the GBD against their critics and has used an even more ridiculous and lazy analysis to do it.

The Great Barrington Declaration and the John Snow Memorandum

Regular readers will likely recall that the Great Barrington Declaration is a statement that arose out of a weekend conference in early October 2020 held in Great Barrington, MA at the headquarters of the American Institute for Economic Research, a free market right wing think tank. This Declaration was written and signed by academics favoring a “natural herd immunity” approach to the pandemic, basically a “let ‘er rip” strategy in order to hasten reaching “natural herd immunity”, with a poorly defined—actually, almost completely undefined—strategy of “focused protection” to protect the groups most vulnerable to severe disease and death from COVID-19, such as the elderly, those with serious co-morbid chronic medical conditions (e.g., type II diabetes and heart disease), all so that society could “reopen” and life could go “back to normal”.

In response to the GBD, a group of public health scientists and physicians published the John Snow Memorandum. This memorandum was named in tribute to John Snow, the 19th century English physician who was one of the founders of modern epidemiology, for his finding that the source of a cholera outbreak in London was a public water pump on Broad Street, leading authorities to remove the pump handle, an action that ended the outbreak. In essence, the JSM countered the GBD by arguing for continuing traditional public health measures (masking, social distancing, etc.) to minimize death and suffering from COVID-19 by slowing its the spread at least until safe and effective vaccines and therapeutics became available. Again, remember that this was before COVID-19 vaccines were available to the public and that at the time these vaccines were still in clinical trials. The memorandum noted, correctly even in October 2020:

The arrival of a second wave and the realisation of the challenges ahead has led to renewed interest in a so-called herd immunity approach, which suggests allowing a large uncontrolled outbreak in the low-risk population while protecting the vulnerable. Proponents suggest this would lead to the development of infection-acquired population immunity in the low-risk population, which will eventually protect the vulnerable. This is a dangerous fallacy unsupported by scientific evidence.

Any pandemic management strategy relying upon immunity from natural infections for COVID-19 is flawed. Uncontrolled transmission in younger people risks significant morbidity(3) and mortality across the whole population. In addition to the human cost, this would impact the workforce as a whole and overwhelm the ability of healthcare systems to provide acute and routine care.

Furthermore, there is no evidence for lasting protective immunity to SARS-CoV-2 following natural infection(4) and the endemic transmission that would be the consequence of waning immunity would present a risk to vulnerable populations for the indefinite future. Such a strategy would not end the COVID-19 pandemic but result in recurrent epidemics, as was the case with numerous infectious diseases before the advent of vaccination.

Indeed, the signatories of the GBD, Martin Kuldorff of Harvard University, Jay Bhattacharya of Stanford University, and Sunetra Gupta of Oxford University, have always seemed—shall we say?—unconcerned that, as a practical matter, it is impossible to protect the vulnerable when a highly contagious respiratory virus is spreading unchecked through the “healthy” population. (After all, who takes care of the vulnerable?) Moreover, as was noted even then, for “natural herd immunity” even to be achievable, immunity after infection must be durable, preferably lifelong. Unfortunately, if there’s one thing that the rise of variants such as Delta and Omicron, the latter of which has been particularly prone to reinfect those previously infected with prior variants of SARS-CoV-2, the coronavirus that causes COVID-19, has shown us, it’s that post-infection immunity (i.e., “natural immunity”) is nowhere near durable enough for such a strategy, given the propensity of this coronavirus to produce variants that can evade immunity from previous infections and waning immunity from vaccination. It is for those reasons that, when I originally wrote about the GBD, I described it as eugenicist in that it basically uses the observation that young people are far less likely to suffer severe disease and die from the disease as an excuse to argue, in essence, “Screw the elderly” and “let COVID-19 rip” in order to achieve “natural herd immunity”. This was especially true given that the GBD was published and promoted before there were safe and effective vaccines available against COVID-19.

Now that there are safe and effective vaccines against COVID-19, even if since the rise of the Delta and Omicron SARS-CoV-2 variants they are no longer as effective as they once were because these variants can evade both post-infection and vaccine-induced immunity to some extent, emphasizing “natural immunity” as somehow being “superior” to vaccine-induced immunity is even more dangerous because it’s clearly not. If the rise of the Delta and Omicron variants, which are transmissible even in the vaccinated, hasn’t demonstrated that to you, I don’t know what will. That’s why it’s particularly disturbing—albeit not particularly surprising—that the Brownstone Institute, founded by former AIER Editorial Director Jeffrey Tucker—who was “in the room where it happened” as the GBD was drafted, describes his new institute as the “spiritual child of the Great Barrington Declaration,” and recruited Kulldorff as its scientific director—has pivoted to spreading antivaccine misinformation about COVID-19 vaccines, even going so far as to compare vaccine mandates to the “othering” that lead to the Holocaust, slavery, and Rwandan genocide and the public health response to COVID-19 to the Chinese Cultural Revolution, all while its signatories claim to have been “silenced“.

Meanwhile, the GBD was hugely influential, with its signatories seemingly having had easy access to the Trump Administration in the US and the Johnson Administration in the UK, whose policies then essentially aligned with the Declaration, as well as leaders like Florida Governor Ron DeSantis, who appointed a GBD devotee and member of the crank organization America’s Frontline Doctors to head up Florida’s public health apparatus and declared that a single positive COVID-19 antibody test proves lifelong immunity and no need for a COVID-19 vaccine ever. Even now, GBD signatories, allies, and flacks falsely argue that “natural immunity” undercuts the case for vaccine mandates, which, according to them, harm patients when required for healthcare workers and damage labor markets. Even after Joe Biden became US President, in this country the GBD remains enormously influential, and it’s hard to miss the rapid push to eliminate mask mandates and block vaccine mandates as having been influenced by it.

Enter John Ioannidis, using bad methodology and a joke of an index to argue that in reality the dominant narrative is not the GBD.

The Kardashian Index: Serious, satire, or a bit of both?

I had always ignored the Kardashian Index (or K-index), viewing it as more of a joke than anything valuable. It was originally proposed in 2014 by Neil Hall in a BMC Genome Biology publication entitled The Kardashian index: a measure of discrepant social media profile for scientists and named after Kim Kardashian, a celebrity who in my estimation is famous mainly for being famous (which was the point of the name) and compares the number of followers a scientist has on Twitter to the number of citations they have for their peer-reviewed work. The idea, clearly, was to denigrate scientists with a large social media presence as not being good scientists. Hall even said so:

While her Wikipedia entry describes her as a successful businesswoman [[2]], this is due most likely to her fame generating considerable income through brand endorsements. So you could say that her celebrity buys success, which buys greater celebrity. Her fame has meant that comments by Kardashian on issues such as Syria have been widely reported in the press [[3]]. Sadly, her interjection on the crisis has not yet led to a let-up in the violence.

I am concerned that phenomena similar to that of Kim Kardashian may also exist in the scientific community. I think it is possible that there are individuals who are famous for being famous (or, to put it in science jargon, renowned for being renowned). We are all aware that certain people are seemingly invited as keynote speakers, not because of their contributions to the published literature but because of who they are. In the age of social media there are people who have high-profile scientific blogs or twitter feeds but have not actually published many peer-reviewed papers of significance; in essence, scientists who are seen as leaders in their field simply because of their notoriety. I was recently involved in a discussion where it was suggested that someone should be invited to speak at a meeting ‘because they will tweet about it and more people will come’. If that is not the research community equivalent of buying a Kardashian endorsement I don’t know what is.

I don’t blame Kim Kardashian or her science equivalents for exploiting their fame, who wouldn’t? However, I think it’s time that we develop a metric that will clearly indicate if a scientist has an overblown public profile so that we can adjust our expectations of them accordingly.

Of course, Hall is on record recently as saying that he had always intended the K-index to be satire mocking the preoccupation with metrics measuring citations, even protesting that there are a number of “tells”. I’ll be honest. Most of his “tells” weren’t super obvious to me as I reread the paper. (Maybe that’s on me. Maybe not. Maybe I’m one of those old farts who didn’t “get it”.)

Let’s at least quote Hall, though:

It’s a dig at metrics not Kardashians. It’s like taking a quiz to see what character from Game of Thrones you are and finding out you’re Joffrey Baratheon. It doesn’t matter – it’s not a real test. Thankfully

— Neil Hall (@neilhall_uk) February 11, 2022

Only if they haven’t read the paper! the tells that the entire premise is satire could not be made more obvious.

But is has had a ~180 citations so maybe I should have tried harder— Neil Hall (@neilhall_uk) February 11, 2022

I suppose the description of picking a “randomish selection of 40 scientists” to examine and that he had “intended to collect more data but it took a long time and I therefore decided 40 would be enough to make a point” were likely two of his “tells,” but in retrospect I have a hard time not coming to the conclusion that this whole exercise, satire or not, backfired rather spectacularly. If the K-index is satire, it’s perhaps a bit too opaque a satire, as certainly Ioannidis appears not to have seen it as satire; either that, or Ioannidis’ use of the K-index is satire that’s even more opaque and less recognizable as satire than the original paper.

I did take one of Hall’s recommendations to heart, however:

I propose that all scientists calculate their own K-index on an annual basis and include it in their Twitter profile. Not only does this help others decide how much weight they should give to someone’s 140 character wisdom, it can also be an incentive – if your K-index gets above 5, then it’s time to get off Twitter and write those papers.

In the interests of full of transparency, I will note that my own K-index, calculated yesterday using Hall’s original formula, varies depending on how I calculate it. The K-index is “calculated as the ratio of Twitter followers divided by 43.3C0.32, where C is the total citations received in one’s career”. Hall came up with that denominator when he fitted a curve to a graph of the number of Twitter followers versus number of citations as a means of estimating how many Twitter followers a scientist should have based on his citations. (Remember, he only used 40 nonrandomly chosen scientists.) In any event, if I use Google Scholar’s estimate of my citations (which, as you will see, Ioannidis says that he does in his paper) my K-index is 104; if I use Web of Knowledge metrics, it’s even higher, at 118. I guess that makes me a “science Kardashian”. Do I care? Not really, given that I have over 69K Twitter followers and Hall’s silly metric says that I should only have 585-664 followers. Instead, I view my Twitter follower count as overachieving on Twitter rather than evidence of underachieving in science!

Seriously, this image kept coming to my mind the more I read Ioannidis’ embarrassment of a paper.

That Ioannidis would, apparently more or less seriously, use such an utterly ridiculous “old man yells at a cloud” metric (that was likely intended to mock the very sort of exercise he uses it to indulge in) to strike back at critics of the GBD and, not coincidentally, of him, boggles the mind. On the other hand, Ioannidis does not have a Twitter account, making his K-index by definition zero, making me think that his entire conclusion from the K-index is that scientists should not have Twitter accounts. I also note that young scientists, who, being relatively new scientists, likely haven’t amassed a lot of publications and citations yet, could easily have a really high K-index with just a modest number of Twitter followers. That’s how ratios work. Does Ioannidis not understand this?

I wasn’t alone in thinking this:

This paper is really something else. The part of me that loves science is grossed out. But the part of me that loves Real Housewives drama is entertained. The commitment to pettiness is exquisite.

— Natalie E. Dean, PhD (@nataliexdean) February 11, 2022

The Kardashian index has always struck me as the quintessential academic version of old people shaking their fists at the sky https://t.co/VCdn7OOl3R

— Health Nerd (@GidMK) February 11, 2022

So now, finally, let’s look at what Ioannidis did. I realize that some of you must be wondering why I took so long to get to this. You’ll just have to trust me that knowing the background is very important, and I hope that after you conclude this section you’ll agree.

Ioannidis versus the John Snow Memorandum

You can tell from the introduction of Ioannidis’ paper that he’s really cheesed about how the GBD and its signatories and supporters have been portrayed negatively, and he definitely vents:

The optimal approach to the COVID-19 pandemic has been an issue of major debate. Scientists have expressed different perspectives and many of them have also been organised to sign documents that outline overarching strategies. Two major schools of thought are represented by the Great Barrington Declaration (GBD)1 and the John Snow Memorandum (JSM)2 3 that were released with a short time difference in the fall of 2020. Each of them had a core team of original signatories and over time signatures were collected for many thousands of additional scientists, physicians and (in the case of GBD) also citizens.4 A careful inspection is necessary to understand the differences (but also potential common points) of the two strategies.4 5 The communication of these strategies to the wider public through media and social media has often created confusion and tension. The communication includes what endorsing scientists state and how opponents describe the opposite strategy. Oversimplification, use of strawman arguments, and allusions of conflicts, political endorsements and ad hominem attacks can create an explosive landscape.4–9

I like that part about ad hominem attacks, given Ioannidis’ previous “punching down” ad hominems against Gideon Meyerowitz-Katz and my perception that this entire article is basically an exercise in ad hominems marshaled to discredit JSM signatories. Maybe his irritation at criticism is part of the reason he treated a likely satirical index with the utter seriousness of a funeral director arranging a memorial service. Nowhere in his paper did I find any indication whatsoever that Ioannidis recognized the ridiculousness of the K-index or that it was likely intended as satire directed at the very sort of bibliometric analyses that he routinely does.

Pray continue, though, Dr. Ioannidis:

It is often stated in social media and media, by JSM proponents in particular, that JSM is by far the dominant strategy and that very few scientists with strong credentials endorse GBD.6–9 GBD proponents are often characterised as fringe, arrogant and wrong by their opponents.6–9 However, are these views justified based on objective evidence on scientific impact or they reflect mostly perceptions created by social media and their uptake also by media?

Here, an analysis is being performed to try to evaluate the scientific impact and the social media visibility of the key signatories who have led the two strategies. Scientific impact is very difficult to evaluate in all its dimensions and no single number exists that can measure scientific excellence and scholarship. However, one can use citation metrics to objectively quantify the impact of a scientist’s work in terms of how often it is used in the scientific literature. Adjustments for coauthorship patterns, relative contributions and scientific field need to be accounted for.10 Concurrently, an additional analysis evaluated the social media visibility of signatories, as denoted by Twitter followers.

Surely Dr. Ioannidis must realize that there are social media platforms other than Twitter. What about Instagram and YouTube, for instance? Or Facebook? Or Tik Tok. (If Twitter irritates Ioannidis so much, Tik Tok will likely break his mind. Maybe it’s best that he never look at Tik Tok.) Also, notice how he’s trying to argue that the JSM narrative doesn’t really dominate in public health science but only appears to dominate because of the social media presences of its signatories. And how does he propose to prove that? First, he looks at H-index metrics for the key signatories of both documents. H-index is a commonly used measure of publication productivity and citation metrics. Mine, for instance, is 26. Using the same methodology, Ioannidis’ H-index is 162. (To be honest, I thought that the discrepancy would be an order of magnitude larger.) Then he goes to Twitter and starts calculating the K-index for the signatories.

Ioannidis is sloppy from the start. He states that he uses the Google Scholar citation index for this reason:

The original publication14 defining the index used citations from Google Scholar. However, given that many signatories did not have Google Scholar pages and Google Scholar citations may be more erratic, Scopus citations (including self-citations) as of 2 April 2021 were used instead. Scopus citation counts may be slightly or modestly lower than Google Scholar citations, and this may lead to slightly higher K-index estimates, but the difference is probably small.

I went back and reread Hall’s original paper proposing the K-index, referenced by Ioannidis. Hall only mentions Google once in the context of Kim Kardashian being the most searched-for person on Google in 2014. In fact, Hall did not use Google Scholar at all, but rather stated explicitly: “I used Web of Knowledge to get citation metrics on these individuals.” So already, I sense some…manipulation and cherry picking here. Did Ioannidis try using Hall’s original formula and find something that didn’t fit with his narrative? One wonders, one does.

Actually, one doesn’t, given how Ioannidis picks the signatories he looks at:

The two documents were retrieved online.1–3 For the main analysis, the 47 original key signatories of the GBD who were listed on its original release online, and the 34 original key signatories who authored the first release of the JSM in a correspondence item published in the Lancet3 were considered for in-depth citation analysis.

He also takes care to use his previous database, the one that he used to denigrate scientists with a media and social media presence, to look at the top 2% of scientists in terms of his citation index. In any event, he’s unable to show that the original Great Barrington Declaration signatories are significantly “better” by these metrics than the original JSM signatories, concluding:

Among the 47 original key signatories of GBD, 20, 19 and 21, respectively, were among the top-cited authors for their career impact, their recent single-year (2019) impact or either. Among the 34 original key signatories of JSM, 11, 14 and 15, respectively, were among the top-cited authors for their career impact, their recent single year (2019) or either. The percentage of top-cited scientists is modestly higher for GBD than for JSM, but the difference is not beyond chance (p>0.10 for all three definitions).

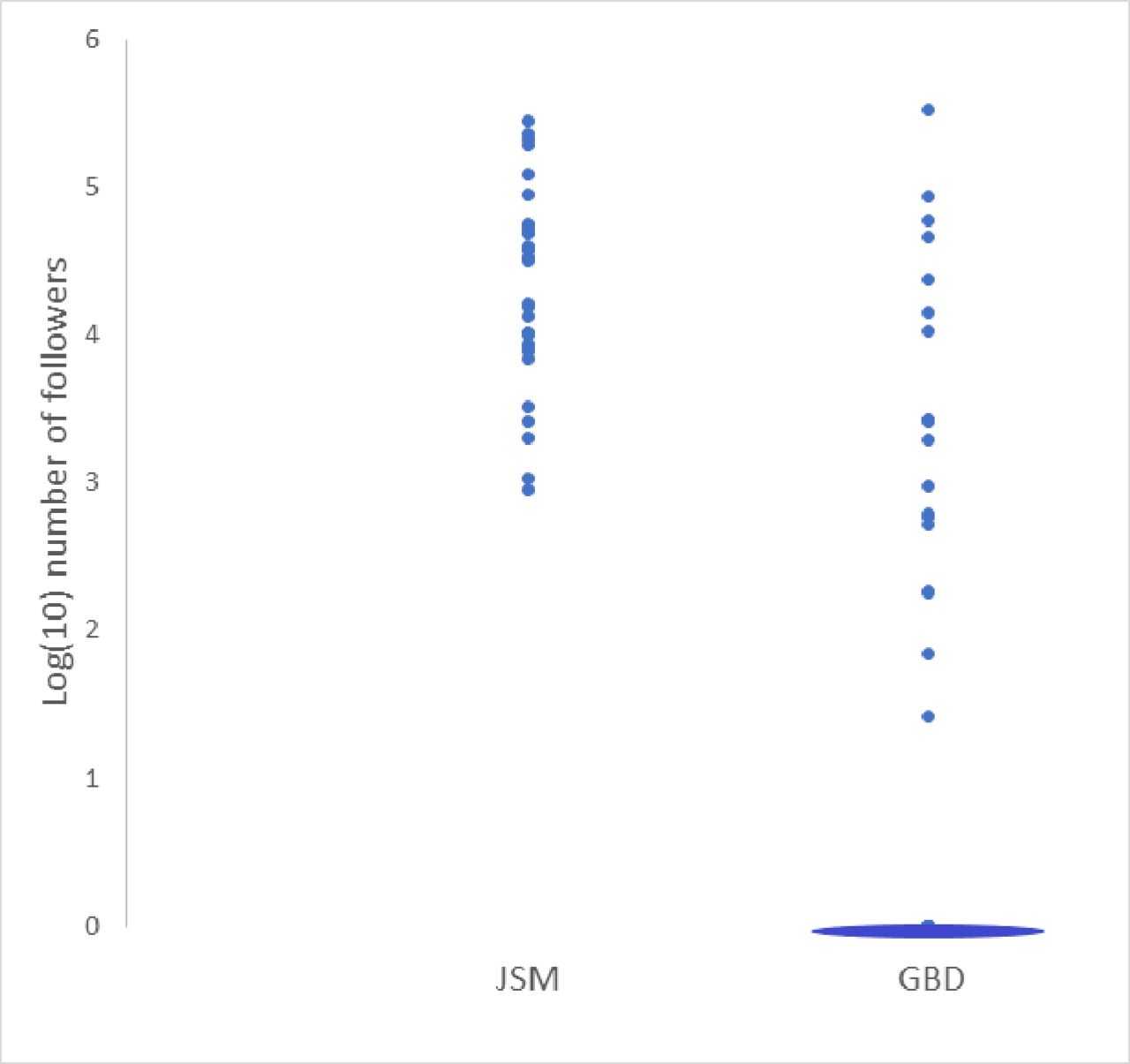

He had a similar lack of luck when it came to comparing how many scientists were among the “top 2%” for each group. Then he produced what has to be one of the most ridiculous figures I’ve ever seen (and the only figure in the paper), showing the Twitter counts:

What does this figure even mean, other than that a lot of GBD signatories don’t have Twitter accounts?

He then notes:

Only 4/47 GBD signatories versus 17/34 JSM signatories had over 30 000 Twitter followers (3/47 vs 10/34 for signatories with over 50 000 Twitter followers). Twitter and citation data, and inferred Kardashian K-indices for the scientists with >50,000 followers appear in table 2. The values of K-index in these scientists were extraordinarily high (363–2569).

An updated search for Twitter accounts and followers on 25 November 2021 found that 22/47 key GBD signatories versus 34/34 key JSM signatories had a retrievable Twitter account (p<0.001). The median number of followers was 0 vs 34 600 (p<0.001). The number of key signatories with >50 000 followers was 13 vs 4.

If I were a peer reviewer for this article, I would have noted that Ioannidis got it wrong describing Hall’s original methodology (such as it was) and appears to have cherry picked an index that he’s more comfortable with. Even accepting that his findings described a reasonable comparison (which they don’t), I’d ask: So what? There’s no evidence that social media presence does or should correlate with citation metrics in the peer-reviewed literature. I’d even point out that, if you look at Table 2, which includes signatories with more than 50K Twitter followers, some of the GBD signatories have K-indices much higher than even mine calculated using Google Scholar; e.g., Martin Kulldorff (363), Michael Levitt 451), and Karol Sikora (2,569).

Of course, if I were a reviewer, normally I would expect to see my peer review of the manuscript published. Why? Because BMJ Open Access also publishes the peer review reports of the papers it publishes, all in the name of transparency. Yet in this one case, a paper written by John Ioannidis as single author (and single author papers are also unusual), it has been observed:

BMJ responded:

A “technical error”? Why is it that I find this explanation rather…convenient.

Whether the failure to post the peer reviews was an honest mistake or something less innocent, Ioannidis’ discussion section made me laugh out loud at a number of points. Running through his commentary is the apparent idea that the number of Twitter followers is a valid metric for influence, coupled with the implicit Carl Sagan effect-like assumption that GBD signatories are better scientists because they don’t have as large a social media presence. For instance, get a load of this backhanded compliment:

The key JSM signatories have a very large number of followers in highly active personal Twitter accounts. The most visible Twitter owners include some of the most cited scientists in the analysed cohorts (Trisha Greenhalgh, Marc Lipsitch, Florian Krammer, Rochelle Walensky, Michael Levitt, Martin Kulldorff, Jay Bhattacharya) and others who have little or no impact in the scientific literature, but are highly remarkable and laudable for their enthusiastic activism (eg, Dominic Pimenta).

You can almost sense Ioannidis patting Dr. Pimenta on the head in a condescending fashion.

Amazingly, Ioannidis then cites Hall’s original paper, a paper that the Ioannidis of 2014 would likely have dismissed as a joke (which it is) as though it were serious scholarship:

Previous work that introduced the Kardashian K-index stated that K-index values above 5 suggest an overemphasis of social media versus scientific literature presence and called such researchers ‘Science Kardashians’.14 This characterisation has not caught up with evolutions in the last few years. Many signatories, especially of JSM, have extraordinarily high K-index, with values in the hundreds and thousands. However, one should account that the volume of Twitter users and followers has increased markedly since the K-index was first proposed, even before the COVID-19 pandemic and even for specialists in disciplines that are not very likely to attract massive social media interest (eg, urology).15 As COVID-19 has attracted tremendous social media attention, Kardashian K-indices are skyrocketing. While no past data were available for the number of followers of the analysed scientists pre-COVID, anecdotal experience suggests that many, if not most, saw their followers increase tremendously during the pandemic. Substantial increases were documented even in the short 7-month interval between April and November 2021.

The massive advent of social media contributes to a rampant infodemic16–18 with massive misinformation circulating. If knowledgeable scientists can have strong social media presence, massively communicating accurate information to followers, the effect may be highly beneficial. Conversely, if scientists themselves are affected by the same problems (misinformation, animosity, loss of decorum and disinhibition, among others)19 20 when they communicate in social media, the consequences may be negative.

Ioannidis, predictably, ignores his own role in contributing to this “infodemic”. He also finally reveals what’s really at the heart of this “paper”. After acknowledging that he had only sampled a small number of other signatories of both documents and that “both citation indices and Twitter followers have limitations in face validity and construct validity as measures of impact”, he nonetheless pivots to claim victimhood for GBD signatories and their narrative:

Acknowledging these caveats, the data suggest that the massive superiority of JSM over GBD in terms of Twitter firepower may have helped shape the narrative that it is the dominant strategy pursued by a vast majority of knowledgeable scientists. This narrative is clearly contradicted by the citation data. The Twitter superiority may also cause, and/or reinforce also superiority in news coverage. In a darker vein, it may also be responsible for some bad publicity that GBD has received, for example, as evidenced by plain Google searches online or searches in Wikipedia pages for GBD, its key signatories or even for other scientists who may espouse some GBD features, for example, scepticism regarding the risk-benefit of prolonged lockdowns. Smearing, even vandalisation, is prominent for many such Wikipedia pages or other social media and media coverage of these scientists. This creates a situation where scientific debate becomes vitriolic, and censoring (including self-censoring) may become prominent. Perusal of the Twitter content of JSM signatories and their op-eds suggests that some may have sadly contributed to GBD vilification.24

In addition, although Ioannidis is mostly correct that the narrative in the media has generally portrayed JSM as the scientific consensus, he fails to recognize that the reason for this dominance is more because JSM has been far closer to the scientific consensus in public health than the GBD, always a minority fringe viewpoint, ever was, rather than anything having to do with Twitter activity of JSM signatories. Indeed, Tim Caulfield and colleagues have argued that what predominated in the media regarding “natural herd immunity” strategies was more false balance than anything else, and I find that argument persuasive, particularly given the effectiveness of organizations like AIER and its offspring the Brownstone Institute.

Ioannidis also casts GBD signatories and supporters as victims, with a bit of what borders on conspiracy mongering:

A major point of attack has been alleged conflicts of interest. However, GBD leaders have repeatedly denied conflicts of interest (see also the site of GBD1). Key JSM signatories appropriately and laudably disclosed upfront all potential conflicts of interest in their original letter publication in the Lancet; the long list is available in public.3 Based on this list, it is possible that JSM leaders have more conflicts than GBD leaders, but the social media superiority of JSM controls also the narrative surrounding conflicts. A similar vitriolic attack has been launched against the American Institute of Economic Research that offered the venue for hosting the launch of GBD.24 Experimental studies show that mentioning conflicts may have the same degree of negative impact as attacks on the empirical basis of the science claims; allegations of conflict of interest are as influential as allegations of outright fraud, when the value of scientific evidence is appraised.25 Non-scientists’ trust is eroded by allusions of conflicts of interest, while it is not affected much by perception of scientific (in)competence (which is also impossible for a non-expert to appraise).25 26 In good faith, reporting of potential conflicts of interest should be encouraged and transparency maximised. However, spurious allegations of hidden agendas and conflicts should not become a weapon for invalidating one or the other document. While exceptions may exist, probably the vast majority of scientists who signed either document simply had good intentions towards helping in a major crisis.

I find it interesting that nowhere does Ioannidis appear to cite the document that, to AIER and GBD signatories, is one of the “vitriolic attacks” against them, namely the article I co-authored with Gavin Yamey (one of the JSM signatories) last spring, in which we documented how right wing forces and think tanks were promoting a GBD narrative and how influential that narrative had been to governments. Indeed, Ioannidis himself was promoting a GBD-like argument against “lockdowns” with his friend Bhattacharya to the Trump administration months before there was even a GBD, and Trump’s COVID-19 czar Dr. Scott Atlas even acknowledged him for it on Tucker Carlson’s Fox News show a month ago. Meanwhile, I’m hard-pressed to find any JSM signatories having been invited to have such close contact with the Trump or Johnson administrations.

Interestingly, Martin Kulldorff and Jay Bhattacharya, both GBD signatories, with Kulldorff being the person who was first enticed by AIER to get the other GBD signatories together for the Great Barrington conference that spawned the GBD, are quite capable of some serious vitriol themselves, for example:

Slander and lies have been hallmarks of attacks on the @gbdeclaration.

This is because lockdown proponents have weak arguments. Their lockdown love has hurt millions via collateral damage & benefited only the laptop class to which many of them belong.https://t.co/M3P9b5BBy4

— Jay Bhattacharya (@DrJBhattacharya) October 12, 2021

Kulldorff himself loves to dismiss doctors critical of the GBD as “laptop class”, claiming false solidarity with working class people who didn’t have the option of working from home during the pandemic, which Kulldorff no doubt did. Kulldorff also has a penchant for referring to his opponents as being a cult:

It is an article of faith contrary to scientific evidence that recovery from COVID does not provide long lasting immunity. Hence, if you have had COVID and do not want to abide by vaccine mandates, you can claim a religious exception for not belonging to the Covidian church.

— Martin Kulldorff (@MartinKulldorff) July 6, 2021

“Covidian church”? (I suppose I should be grateful that Kulldorff refrained form using “Branch Covidian”, a favorite of antivaxxers to describe scientists.) Kulldorff does know, doesn’t he, that referring to scientific findings as religion and scientists you don’t like as cult members is exactly the same thing that antivaxxers love to do. Similarly, Kulldorff and Bhattacharya, the latter a good friend of Ioannidis’, have accused critics of the GBD of being “part of the mob”, egoists “making the poor suffer for their egos”, and so deluded that they “know lockdowns don’t help but they continue”.

Just last week, a Stanford University medical student named Santiago Sanchez challenged GBD signatory Dr. Bhattacharya. I think it’s worth citing some of the Tweets:

I don't know who you are, but you're very bad at mind reading. I think Fauci's decisions during the pandemic (and maybe before) have led to countless unnecessary deaths. https://t.co/CtN27XTTt4

— Jay Bhattacharya (@DrJBhattacharya) February 11, 2022

Not only did Bhattacharya sic his Twitter followers on Sanchez, but, suspiciously, a “charity” affiliate of the GBD known as Collateral Global Charity called him a snake. When criticized harshly for it, whoever runs its Twitter account deleted the original Tweet and then unconvincingly claimed that it had been hacked:

One wonders if the ever-so-civil Ioannidis, who decries any form of ad hominem and nastiness in his search for only the purest possible scientific discourse has had a little chat with his good buddy Jay Bhattacharya and his other friends at the GBD about how bad it looks to “punch down” this way. I won’t even go into how Bhattacharya also challenged Santiago to a debate moderated by—I kid you not!—Dr. Vinay Prasad.

On second thought, I can’t resist:

I couldn’t resist giving this intrepid medical student, whom I admire for his bravery in standing up to a famous professor at his medical school, a little advice about not debating cranks, using my SBM post from a couple of weeks ago:

It’s not and don’t do it. @DrJBhattacharya knows that the power differential alone makes such a “debate” propaganda, not a scientific debate. https://t.co/PIoanGrDWt

— David Gorski, MD, PhD (@gorskon) February 13, 2022

I’ll stop now, because I know that some of you don’t like a lot of embedded Tweets, but I think that in this case it is more than justified to feature them. In addition, I realize that this is a bit of a tu quoque fallacy to bring this up, but on the other hand the hypocrisy of GBD signatories and advocates never ceases to astound me. Indeed, Ioannidis’ paper can be viewed in this context as a rather obvious ploy to portray JSM signatories as social media prima donnas, as unserious “science Kardashians”, and he’s so intent on such an ad hominem attack that he appears to have completely missed the point about the K-index and took it as a serious metric supported by research; that is, unless he has written a satire so incredibly subtle that no one can detect the satire.

I’ll conclude by asking about John Ioannidis the same thing that I ask about every scientist and physician whom before the pandemic I had considered reasonable or even someone to be admired for their scientific and medical rigor: Did something about them change, or where they always like this and I just didn’t see it? For someone like Dr. Vinay Prasad, I think that the answer is the latter explanation. In the case of John Ioannidis, I still don’t know. Everyone with whom I’ve interacted who knows him says he’s such a supportive, honorable, and nice man. A paper like his K-index paper, however, is not consistent with such a characterization, and that’s why more and more I’m leaning towards the latter explanation for his behavior and scientific takes since the pandemic hit. Whatever the reason, I’ll conclude once again that, sadly, Ioannidis appears to have come full circle. He first became famous because of his paper about how most scientific findings turn out to be wrong, and now he’s contributing to the very problem that he identified.

And now he’s gone beyond that and led me to write a sentence that I never in my wildest dreams would have imagined and actually use it as a title of a blog post.