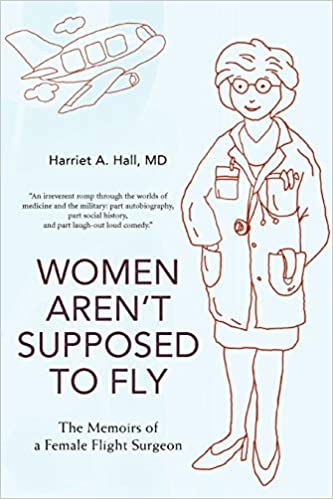

In the June 17, 2021 issue of The New England Journal of Medicine Dr. Erica Kaye wrote a “Perspective” piece titled “Misogyny in Medicine”. It made me re-evaluate my own experiences with sexist attitudes. In my book Women Aren’t Supposed to Fly: The Memoirs of a Female Flight Surgeon I described several examples of how I was treated unfairly because I was a woman. When faced with overt discrimination, I was advised by an inspector general not to report it because it would be explained away by the perpetrator and would only harm my career. I never encountered anything approaching overt sexual harassment or assault, but Dr. Kaye opened my eyes to the concept of subtle microaggressions. It made me question a lot of other things that had happened to me during my career and that continue to happen.

Dr. Kaye says that despite increased lip service about the need for gender equity in medicine, misogyny is pervasive in clinical and academic medicine. Women report high rates of discrimination and harassment. According to the National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM) at least half of female medical students experience sexual harassment. This “continues into training and faculty careers and correlates significantly with burnout”. Dr. Kaye says that women tend to believe accounts of misogyny at face value, whereas men “interrogate the data, request proof, or seek alternative explanations”. Men tend to see reports of discrimination as outliers, whereas women recognize it as the status quo.

Statistics show that women in medicine make less money and hold fewer leadership positions than men, and women of color bear at least double the burden. Dr. Kaye says when men challenge authority they are described as bold, assertive, or confident; women who do the same are disparaged as aggressive, rebellious, or unprofessional. When she calmly disagreed with a male superior, in response he raised his voice and threatened her job. She realized “that I would be held responsible for ‘provoking’ him and that I needed to absorb his anger and respond with tranquility and equipoise”.

Dr. Kaye gives examples of what she calls microagressions from her superiors:

- You should take those barrettes out of your hair. You look like a little girl.

- Your first responsibility is taking care of your husband.

- My wife stayed home with our kids. It’s too bad your kid is in day care.

- Your butt looks flatter. Have you lost weight?

She points out that “retaliative microaggressions and discrimination are difficult to prove, readily slipping through policy cracks”. She believes that changing the culture of medicine hinges on the sharing of stories. She encourages women to saturate the mainstream dialog, to flood the discussion with their personal stories of sexism.

As I thought about this, I noticed a potential pitfall. It would be all too easy to blame everything on misogyny. I could look back on every interaction with a male during my career and ask whether it might be an example of subtle microaggressions, whether it might have been different if I were not a female. Paranoia would ensue.

Conclusion: misogyny in medicine is real

Dr. Kaye brings up some excellent points. Yes, misogyny continues in medicine. Yes, incidents need to be reported, and we need to be more aware of what she calls microaggressions. But it would be all too easy to get carried away and engage in paranoia and conspiracy theories.

I just noticed that in the list of editors on the SBM website, my name is listed last, only after the names of two editors emeritus. Did that happen by chance, or should I suspect subtle misogyny? I could complain loudly of mistreatment, but I won’t. I’m happy to give them the benefit of the doubt and say nothing. Let’s not forget common sense and moderation in all things.

Misogyny in Medicine

Misogyny persists in clinical and academic medicine. We need to be aware of subtle micro aggressions and report abuses, but we mustn’t get carried away into paranoia and conspiracy theories. We should be guided by common sense and moderation in all things.