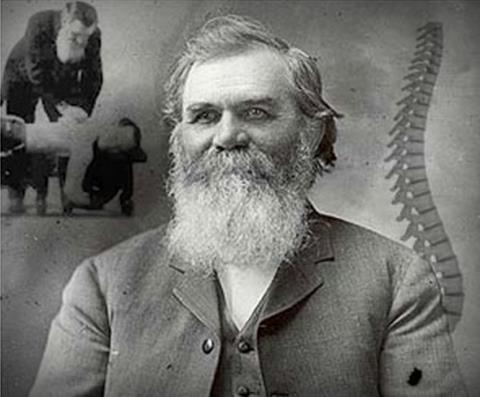

Daniel David Palmer, creator of the nebulous subluxation and father of chiropractic.

It has been almost five years to the day since I wrote my first post in “The DC as PCP” series. These posts (listed here) chronicle the continuing battles among various factions within the chiropractic profession over the subluxation and its many iterations, educational requirements for chiropractic colleges, their legal scope of practice, and whether chiropractors are – or are not—primary care physicians (PCPs). At its heart, the controversy boils down to this essential issue: what is “chiropractic” and what is it that chiropractors do? Or, perhaps, should do.

At one end of the spectrum is the straight chiropractor, who wants to make his living detecting and correcting subluxations for all manner of problems. These are the chiropractors who claim newborns need adjustments for “birth trauma” and maintenance care is necessary to good health. At the other end are those promoting the idea that chiropractors are primary care physicians capable of seeing the undifferentiated patient, form a differential diagnosis, and either treat the patient or coordinate the patient’s care with other health care professionals.

Neither has any basis in reality. The subluxation is a chiropractic fiction. And the notion that chiropractors have the necessary education and training to act as primary care physicians is no less a fiction.

Apparently unrepresented in this battle is the chiropractor who wants to see the profession as evidence-based spine care specialists based on a model of specialty care like podiatry and dentistry.

The causus belli in the current skirmish is the Council on Chiropractic Education’s (CCE) second draft of a revision of the 2013 Accreditation Standards for chiropractic colleges. The CCE is the sole agency with the authority, granted by the U.S. Department of Education, to accredit chiropractic colleges and to monitor their activities for compliance with its standards for chiropractic education. Getting and keeping accreditation is extremely important for the colleges – without it, their students would not have access to federal student loans and their graduates would not be eligible for state licensing. The CCE’s educational standards for accreditation have become a battleground on which various chiropractic factions duke it out over their competing philosophies.

A contentious history

Back in 2010, the CCE tried to eliminate the phrase “without the use of drugs or surgery” from its definition of chiropractic, as well as the word “subluxation,” and any requirement that students learn to “adjust” the putative chiropractic subluxation. The more conservative element smelled a nefarious plot to turn chiropractic away from its roots and set it on a path toward chiropractors practicing as some version of an MD/DO primary care physician.

This proposed revision of CCE educational standards was part of a larger effort to rebrand chiropractors as PCPs by expansion of the chiropractic practice acts and chiropractic regulatory board rulemaking, not always successfully. Chiropractors’ attempts to transform themselves via legal fiat into PCPs (or, at least, move in that direction) have been beaten back by a strange-bedfellows combination of straight chiropractors, medical doctors, and pharmacists in New Mexico, Colorado, and Texas.

The American Chiropractic Association (ACA) jumped on the PCP bandwagon by simply announcing that chiropractors are, indeed, PCPs, in the ACA News, an effort promptly demolished by Harriet Hall. The Journal of Chiropractic Education weighed in with an article claiming that the National University of Health Sciences, an accredited chiropractic college, was ready to train chiropractors as PCPs. Dr. Hall took a dim view of that as well:

The data they collected don’t even begin to support that assertion. The study is not only meaningless, it demonstrates a gross misunderstanding of the education required to practice competent primary care.

The ACA’s American Board of Chiropractic Specialties, a pseudo-American Board of Medical Specialties, approved a specialty called “Chiropractic Diagnosis and Management of Internal Disorders” practiced by “chiropractic internists.” One can become a “diplomate” of the American Board of Chiropractic Internists by taking a series of 26 weekend courses in hotel conference rooms and taking a test.

The straights weren’t satisfied with simply having input into the three drafts that it took to reach a final version of the CCE’s educational standards. They took their fight to the U.S. Department of Education to challenge the very authority of the CCE to accredit chiropractic colleges. A beleaguered CCE ended up getting itself put on a probation of sorts by the Department for one year while it set its house in order, finally gaining recognition for another 3 years in 2013.

As part of its effort to paper over the considerable differences between the straight and the PCP factions, and all sub-factions in between, the CCE spent considerable effort on the subluxation and its place in chiropractic education in redrafting its educational standards. Its solution was to invent yet another name for this nebulous chiropractic creation. As the CCE explained in an “open letter:”

Despite its historical legacy in the profession, a number of educational programs and practitioners have opted to use other terms, such as joint fixation or joint dysfunction. Even the Association of Chiropractic Colleges (ACC) has not reached a unified definition or specific criteria for subluxation, despite its own task force addressing this issue. The 2012 Standards opted to use a combination phrase, ‘subluxation/neuro-biomechnical dysfunction.’

We’ll return to that term — “subluxation/neuro-biomechnical dysfunction” – in a moment, as it plays a role in the current controversy.

More recently, the ACA announced the establishment of a “College of Pharmacology and Toxicology,” yet another effort that upset the International Chiropractors Association (ICA), which represents the straights, who saw it as a suspicious move toward lobbying for prescription privileges. The ACA’s wholly unconvincing response to this criticism was to try to distinguish the word “pharmacology,” which, to them, is simply understanding drugs, from “pharmacotherapy,” which is actually prescribing drugs. The ACA argued that this semantic distinction meant they absolutely did not intend to move in the direction of chiropractic prescribing rights. (It’s all about semantics again.) Unfortunately for them, the ACA’s own proposed model scope of practice act includes “Full . . . Prescription Authority” for chiropractors, which makes their explanation even more unconvincing. On top of that is the fact that the “College” will operate under the jurisdiction of the Council on Diagnosis and Internal Disorders, whose avowed purpose is to create chiropractic “internists.” Really, one must admire the ACA’s temerity in even attempting to tackle the ICA’s objection.

The current draft of CCE standards for chiropractic colleges

With that background, we’ll march forward into the current skirmish surrounding the second draft of the CCE’s proposed accreditation standards, an attempt to revise the 2013 standards that were the subject of previous battles. Apparently, CCE accreditation standards have a very short shelf life.

Two chiropractic organizations have filed their objections to this draft. Not unexpectedly, one of them is the ICA. (The ICA’s summary of objections was in an email, so I can’t link to it.)

The ICA’s first gripe relates to patient management. The CCE draft standards require that the student be able to develop a “management plan” for the patient that includes “specific therapeutic goals and prognoses.” The ICA has a bone to pick with this – they want to delete the term “therapeutic,” because clinical goals are not always ‘therapeutic.'”

ICA is was especially concerned to see that the standards language was sufficient to support all appropriate forms of chiropractic case management and not just ‘therapeutic’ care based on episodic symptomatology.

Why? Well, unstated here is the ICA’s devotion to “maintenance” or “wellness” care – the notion that all patients require regular “spinal checkups” to detect subluxations and, if subluxations are found, to “correct” them with “adjustments.” (One does wonder if there was ever a chiropractic maintenance care exam that didn’t uncover a subluxation.) Which brings us to another ICA objection.

For the first time, apparently, the CCE has included what they call a “meta-competency” requirement in adjusting/manipulation, which pleases the ICA. The fly in this ointment is that the skill required is not just “adjustment” but “adjustment/manipulation.” According to the ICA, they are not the same thing. The ICA is correct. “Adjustment” has always referred to a method of “correcting” the phantom subluxation. Other professions perform manipulation, or, as the ICA would prefer to call it, “other forms of manual care,” but, as the ICA says, “only doctors of chiropractic administer chiropractic adjustments.” The reason is that no other profession believes the chiropractic subluxation exists or, obviously, that it can be “adjusted,” but they don’t bring this up.

One suspects the CCE is trying to gloss over this difference by pretending adjustment is just another term for manipulation, a perfectly legitimate form of manual therapy, and not a method to correct the subluxation, which they would love to get rid of, at least in its straight chiropractic iteration.

And speaking of the subluxation, another organization, the International Federation of Chiropractors and Organizations (IFCO) also has a quarrel with the CCE regarding terminology. (IFCO motto: “Vertebral Subluxation . . . Nothing More . . . Nothing Less . . . Nothing Else.”) In the current draft standards, as part of the requirement that the student learn how to adjust/manipulate, he must know how to “employ methods to identify subluxations/segmental dysfunction of the spine and/or other articulations.” (Emphasis added.) Thus, we find that a mere 2 years after the CCE thought up the term subluxation/neuro-biomechical dysfunction in its continuing quest to define the subluxation by creating new names for it, “neuro-biomechanical dysfunction” is tossed aside in favor of “segmental dysfunction.” The CCE also uses the terms joint fixation and joint dysfunction.

The IFCO thinks the CCE needs to clean up this semantic mess.

There are significant operational and epistemological differences. Implicit in the term vertebral subluxation are both biomechanical and neurological elements. A fixated or tender joint might represent one manifestation of vertebral subluxation, not synonym for vertebral subluxation. The implication that they are the same leads to confusion and ambiguity.

No kidding on the confusion and ambiguity. But I’d venture to say that it’s the chiropractors’ failure, after 120 years, to define the subluxation, validate methods for finding one, determine the clinical significance of the subluxation, and demonstrate convincingly that treating it improves patient outcomes, leads to the confusion and ambiguity. Not what to call it.

A few years ago, the cart-before-the-horse futility of trying to settle on a name for the subluxation was called out by the authors, themselves chiropractors, of “Subluxation: Dogma or Science?”

The subluxation is identified by a great many names, but neither the abundance of labels nor efforts to reach consensus on terminology tell us anything about the validity of the construct. Nelson points out that “…framing the subluxation debate as a semantic issue, resolvable by consensus, is precisely the same as asking whether we should refer to the spaceships used by aliens as flying saucers or UFOs.” Neither adoption nor rejection of the term subluxation or any of its myriad synonyms will resolve the problem created by assuming a priori that subluxation is clinically meaningful. If and when we demonstrate that there are alien spaceships hovering over us, we suspect an appropriate terminology will develop on its own.

Unfortunately, no one paid any attention, and the semantic shenanigans continue.

“Primary Care Chiropractic Physicians”

Both the ICA and the IFCO object to the CCE’s use of the terms “primary care” and “primary care chiropractic physician.” Here again, there is disagreement over just what those terms mean.

The new draft of the CCE standards requires that all accredited educational programs produce graduates who are able to function as “primary care chiropractic physicians.” In defining what it calls “meta-competencies,” which must be taught to every student, there is little indication that the chiropractor’s skill set should be limited to musculoskeletal issues. Although students must learn to detect a “subluxation/segmental dysfunction,” and perform an “adjustment/manipulation,” the requirements are otherwise described in terms that are quite broad.

For example, in achieving a “meta-competency” in “assessment and diagnosis,” a student must demonstrate the ability to:

1) Develop a list of differential diagnosis/es and corresponding exams from a case-appropriate health history and review of external health records.

2) Identify significant physical findings and follow-up through a physical examination, application of diagnostic and/or confirmatory tests and tools, and any consultations.

3) Generate a problem list with diagnosis/es after synthesizing and correlating data from the history, examinations, diagnostic tests, and any consultations.

Students must also be able to “develop an evidence-informed management plan appropriate to the diagnosis” and “refer for emergency care and/or collaborative care as appropriate.” This doesn’t seem to contemplate that the chiropractor might step out of the picture once the referral is made, which is suspiciously like the role of the primary care physician in serving as a medical home and care coordinator.

For comparison, here’s how the American Academy of Family Physicians, quite similarly, describes primary care:

[A] generalist physician who provides definitive care to the undifferentiated patient at the point of first contact and takes continuing responsibility for providing the patient’s care . . . . [T]he personal primary care physician serves as the entry point for substantially all of the patient’s medical and health care needs – not limited by problem origin, organ system, or diagnosis. Primary care physicians are advocates for the patient in coordinating the use of the entire health care system to benefit the patient.

However, the CCE is taking a “big-tent” approach to teaching the required skills. It does not “define or support any specific philosophy regarding the principles and practice of chiropractic” nor do its educational standards “support or accommodate any philosophical or political position.” Each school, it says, is “free to determine its own method of meta-competency delivery and assessment.” So, cleverly, or perhaps as a survival strategy, the CCE allows each school to superimpose its own philosophy onto this educational template. If the straights want to read the requirements as allowing them to teach the overarching significance of the subluxation and how to detect and correct it with adjustments, so be it. If schools with more expansive agendas want to rebrand chiropractors as primary care physicians or chiropractic internists, that’s ok too.

Even with the implied promise that the straight schools will be left alone, the ICA doesn’t like the CCE’s expansive definition of primary care. It thinks “primary care” is simply synonymous with “portal of entry,” and that a “primary care chiropractic physician” is:

A direct access, doctor level health care professional qualified to serve as the patient’s first point of contact within the health care system, without referral from any other professional.

According the Chair of the ICA’s committee on accreditation issues, this will “help avoid misrepresentation of what is actually meant and limit expansiveness and inappropriate interpretations in the direction of medicine and medical procedures.” But “expansiveness” is just what some chiropractic factions are after and it’s doubtful the ICA will convince the CCE to redefine primary care as a synonym for portal of entry.

However one defines the chiropractor’s role in health care, the ICA doesn’t want students forced into “interprofessional education” either, another new CCE-required meta-competency, including multi-disciplinary clinical practice settings for students. I have to agree with the ICA that this is a difficult goal to achieve. It would require the cooperation of the medical community, which may be reluctant to allow chiropractic students into their clinical training settings, such as teaching hospitals, private physicians’ offices and health care clinics. One can well imagine that this prospect will seem even less appealing to medical educators if chiropractors are trying to pass themselves off as PCPs.

The IFCO objects to the whole notion that chiropractors are primary care practitioners as well, and points out that:

Many, if not most procedures termed “primary care” as commonly defined, are not within the scope of chiropractic practice in any jurisdiction. These include, by example, family planning; immunization against the major infectious diseases; prevention and control of locally endemic diseases; appropriate treatment of common diseases and injuries; and provision of essential drugs.

Which is absolutely true. Whatever you might otherwise think of the IFCO, it has put together a compilation of accepted definitions of primary care that nicely demonstrates its point. Its solution is to use the term “doctor of chiropractic” instead of “primary care chiropractic physician” and eliminate the CCE’s definition of “primary care” from the standards altogether. Seems reasonable.

The danger here, of course, is that the scope of chiropractic practice can be changed by the legislature in any state. As we have discussed many times on SBM, the legal scope of practice of CAM providers is often at odds with their actual education and training. Especially disturbing are chiropractors’ attempts to push for a scope of practice that defines what they can do by reference to what they are taught in chiropractic school. This is why the CCE’s standards are so important. Left with plenty of room to improvise, all manner of things can be loaded into the chiropractic practice acts by default to whatever the chiropractic schools choose to teach. Kansas, North Dakota and Oklahoma already reference chiropractic education as a metric for determining chiropractic scope of practice. In the last two legislative sessions (2013-14 session here), bills to define chiropractic in similar terms were defeated in New Mexico and Hawaii.

No doubt the battle will continue.