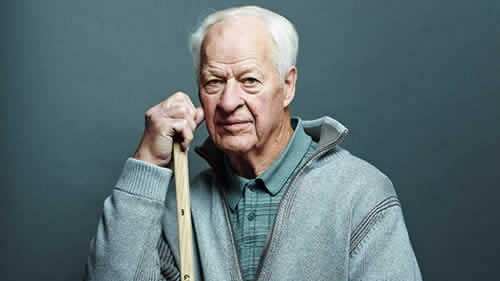

Another Christmas has come and gone, surprisingly fast, as always. I had thought that it might make a good “last of 2014” post—well, last of 2014 for me, anyway; Harriet and Steve, at least, will be posting before 2014 ends—to do an end of year list of the best and worst of the year. Unfortunately, there remains a pressing issue that doesn’t permit that, some unfinished business, if you will. I’m referring to a story I commented on last week, specifically the credulously-reported story of how 86-year-old hockey legend Gordie Howe is doing a lot better after having undergone an experimental stem cell therapy for his recent stroke. As you might recall at the time, I saw a lot of holes in the story. It turns out that over the last week there have been developments that allow me to fill in some of those holes. Unfortunately, other holes still remain.

First, a brief recap is in order (You can click here for a more detailed timeline). Gordie Howe suffered a massive stroke on October 26, leaving him hemiplegic and with serious speech impairment. Since then, judging from various media reports, he has been slowly improving, although not without significant setbacks. We also know that Howe suffers from significant dementia. Out of the blue, a press release issued on December 19 by the Howe family announced that on December 8 and 9, Gordie Howe “underwent a two-day, non-surgical treatment at Novastem’s medical facility. The treatment included neural stem cells injected into the spinal canal on Day 1 and mesenchymal stem cells by intravenous infusion on Day 2.” His response was described as “truly miraculous,” although, as I pointed out in my post, it’s not clear exactly what “miraculous” meant, given conflicting contemporaneous news accounts before the Howe family press release, particularly his hospitalization from December 1 to 3 for a suspected stroke that turned out to be dehydration.

I noted a number of problems with the story, the first of which is that Howe was clearly not eligible for the clinical trial offered by Stemedica, a company in San Diego that manufactured the stem cells used. Another glaring issue was my inability to locate any description of an actual clinical trial for stroke offered by Novastem. I could find no such trial listed in ClinicalTrials.gov, and you, our intrepid readers, searched the registry maintained by the Mexican Federal Commission for the Protection Against Sanitary Risk (COFEPRIS) and were not able to find any registered clinical trials for stroke being carried out by Clínica Santa Clarita, the clinic Novastem operates. What you, our intrepid readers, did find were trials of stem cells for:

I did the search again over the weekend, and there were no further trials that I could find.

So it was that I concluded my post having grave doubts that there actually was a clinical trial run by Novastem using Stemedica’s allogeneic mesenchymal stem cells to treat stroke. To me, it all looked very fishy, as though Dr. Maynard Howe (CEO) and Dave McGuigan (VP) of Stemedica Cell Technologies, knowing that Gordie Howe was not eligible for their clinical trial for stroke, given that Howe’s stroke was less than two months prior and the trial required that the stroke be six months old and that no neurologic improvement had occurred for two months, had shunted him to Novastem to be treated anyway. Looking at Novastem’s website, in marked contrast to that of Stemedica, I saw no evidence of clinical trial activity at all, other than following up with patients by keeping in touch with their doctors. What I did see was (to me, at least) a very dubious-appearing stem cell clinic that charged patients large amounts of money for stem cells, cash on the barrelhead. (Seriously, Novastem only accepts cash or money transfers.) With Christmas fast approaching, I did not expect to find out anything more about this story before the end of the year.

My expectation was upended on Christmas Eve.

In which I am sent a press release

On the afternoon of December 24, as I was preparing to head over to my aunt’s house for the traditional Gorski family Christmas Eve celebration, I received an e-mail from a woman named Kimberly Stoddard, who represents The Townsend Team, a marketing and branding firm representing Stemedica. Ms. Stoddard referred me to a press release entitled “Novastem Treats First Patient Using Stemedica’s Mesenchymal and Neural Stem Cell Combination Therapy for Ischemic Stroke“:

TIJUANA, Mexico, Dec. 24, 2014 /PRNewswire/ — Novastem, a leader in regenerative medicine, announces the treatment of its first patient in its study for ischemic stroke at Clinica Santa Clarita. According to the American Stroke Association, ischemic strokes account for 87 percent of all stroke cases. Novastem continues to enroll qualified patients in the study, entitled “Internal Research Protocol in Combination Therapy of Intravenous Administration of Allogeneic Mesenchymal Stem Cells and Intrathecal Administration of Neural Stem Cells in Patients with Motor Aphasia due to Ischemic Stroke.” All participants receive a unique, combination therapy using a method covered by a United States patent owned by Stemedica Cell Technologies for the therapeutic use of its allogeneic, ischemia-tolerant mesenchymal and neural stem cells.

My first reaction went along the lines of, “Well, that’s odd. Who issues a press release like this on Christmas Eve? Nobody’s paying attention now.” My second thought was a speculation, “Well, maybe that was the point.” My third question was whether this press release was a reaction to the skeptical posts about Gordie Howe’s treatment with stem cells by Paul Koepfler and myself. In checking to see if Dr. Koepfler had written anything else, I found a follow-up post by him dated December 23 and entitled “Response from Stemedica on Questions on Stem Cell Treatment of Howe“. It’s not very informative, its only new information being that Stemedica didn’t write the press release (its author was later revealed to be Gordie Howe’s son Murray) and that “Stemedica is not a sponsor of the clinical trial referenced below; that is Novastem…”

And now we have Novastem and Stemedica’s joint press release.

It was immediately obvious to me (and anyone else who had paid attention to the stories about Gordie Howe) that this first patient treated was, in fact, Gordie Howe, although the press release quite properly did not name him. One thing I wrote in my original post that this press release did confirm for me is that the principal investigator (PI) of this “trial,” if trial it is, appears grossly unqualified to be running a clinical trial on something as tricky as testing whether stem cells might help stroke victims. If you don’t believe me, take a look at Dr. Clemente Humberto Gil Zúñiga’s CV posted on the Novastem website. He’s a geriatrician who practices at Hospital Angeles Tijuana and appears to possess no relevant clinical trial experience that I can find listed. Certainly his publication record shows nothing related to stem cell biology or clinical trials.

I’m a clinical trial maven. That’s why I had hoped to learn a bit more about the trial design, but the press release, not surprisingly, reveals little. Still, there are clues here. First off, this trial is designed to examine the effect of this stem cell treatment on aphasia. Briefly, the general term “aphasia” describes acquired speech/language difficulties due to brain injury or damage in which part or all of speech is impaired with no effect on intelligence. For example, in simple terms a patient with expressive aphasia can understand what others say and knows what he wants to say but just can’t say it. I have personally witnessed a family member with this after a stroke. It’s incredibly frustrating to the patient. There are other forms of aphasia, such as receptive aphasia, but it’s not important for purposes of this post to describe them now. All you need to know is that various forms of aphasia are very common sequelae of strokes. It struck me as odd that Gordie Howe would be on an aphasia trial, because (1) his post-stroke impairments go way beyond aphasia, judging from the news reports and (2) he suffers from significant dementia, which would make determining aphasia scores difficult. We don’t know for sure how bad Howe’s dementia is, but in some news reports I’ve seen it’s been described as “severe.”

Next, there is this part of the title of the protocol, “Internal Research Protocol.” Right away this tells us that there is no external funding; it’s an internal protocol. Next, if we look at the paragraph above, we see a curious sentence stating that the “protocol is approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Clinica Santa Clarita, which is federally registered and licensed by the Federal Commission for the Protection against Sanitary Risk (COFEPRIS), a division of Mexico’s Ministry of Health.” What does this mean? Not being familiar with Mexican law with respect to clinical trials, as I am with US law, I am struck by how this is described. In the US, we would say that a trial is IRB approved (Institutional Review Board), that there is an IND (investigational new drug) application, and that the trial is registered with the FDA, which presumably any company would do because trials being used as a basis for drug approval have to be registered with the FDA and conform to all the rules for clinical trials, including the Common Rule. In this press release, we see from the sentence structure that it is the clinic, Clinica Santa Clarita, that is “federally registered and licensed by the Federal Commission for the Protection against Sanitary Risk (COFEPRIS), a division of Mexico’s Ministry of Health,” not the trial. I suspected that this sort of registration is not the equivalent of what goes on in the US. Boy, was I correct, far more so than I thought! I’ll explain in the last section, when I look at this trial in more detail. First, however, I want to address a news story published Friday.

What really happened?

On Friday, a reporter who’s interviewed me before, Bradley Fikes, published a news story about Gordie Howe in U-T San Diego entitled “Did stem cells really help Gordie Howe?” This is the first—and so far only—attempt by a mainstream media outlet that I’ve seen to cast a skeptical eye on the whole story as presented. In the story, Fikes reports a number of disturbing aspects of this case.

First, we learn from Dr. Murray Howe, Gordie’s son, how he’s doing:

Howe, 86, suffered the stroke in late October, leaving him unable to walk and disoriented. He began improving within hours after receiving the stem cells in early December, said Dr. Murray Howe, a radiologist and one of Howe’s sons. For example, Howe insisted on walking to the bathroom, which he previously could not do.

“If I did not witness my father’s astonishing response, I would not have believed it myself,” Murray Howe said by email Thursday. “Our father had one foot in the grave on December 1. He could not walk, and was barely able to talk or eat.”

“Our father’s progress continues,” the email continued. “Today, Christmas, I spoke with him on FaceTime. I asked him what Santa brought him. He said ‘A headache.’ I told him I was flying down to see him in a week. He said, ‘Thanks for the warning.'”

Yes, Gordie Howe did appear to have “one foot in the grave” on December 1. I even reported it in my last post that he looked bad then and everyone thought that he had had another big stroke. Fortunately, he was just dehydrated and rapidly improved with hydration, as several contemporaneous news stories reported before Howe was ever taken to Tijuana for Novastem’s stem cell treatment.

In fairness, I have to acknowledge that there’s more:

A physical therapist who works with the elder Howe, Deirdre Bailey, said Thursday he showed “marked improvement” when she saw him a few days after the stem cell therapy. Previously able to stand only with extensive help, Howe could stand and walk on his own, although unsteadily and in need of close watching.

Bob Jones, a speech language pathologist who has worked with Howe over the last several weeks, said Thursday that Howe greatly improved his understanding and response to questions after the treatment. He was further improved when seen on Thursday of last week.

“He interacts more than he had before,” Jones said. “He responds appropriately to such things as proverbs, idioms similes,” when prompted to complete them. His speech, almost unintelligible before, is less difficult to understand.

So it does sound as though Gordie Howe is doing better, which is great. However, it’s not possible to tell whether this improvement is due to his stem cell infusions. Remember, just before he went to Tijuana, he had recently been hospitalized for dehydration that had rendered him unresponsive. Before that, he had had a rough November, with setbacks but overall small improvement. Indeed, if you look at the news coverage of Howe’s condition since October 26, you’ll see reports of rapid recovery mixed with reports of setbacks. It’s clearly been a bit of a rollercoaster ride, which makes it very hard to tell if any improvement is due to anything other than the nature the stroke, or if it’s durable. The point is simple: Given Howe’s fluctuating, but overall slowly-improving condition, it’s hard to attribute his current condition to the stem cell treatment.

As hard as it is for Dr. Murray Howe to realize, as well, human beings are very prone to observational quirks. In fact, it’s clear that he doesn’t recognize it, given that the story reprints a complete e-mail by him in which he declares himself “an expert in my dad’s medical condition” and “confident that my credentials attest to my capacity to be a reliable witness.” (He also stated emphatically that he had written the entire December 19 press release announcing Howe’s “miraculous” progress since undergoing stem cell treatment.) Unfortunately, doctors are arguably among the worst when it comes to overestimating our capacities to be reliable witnesses. Unlike our unfortunately-frequent view of ourselves as being objective observers, unless we make a conscious, skeptical effort not to be, we are just as prone to confirmation bias, in which observations that agree with our beliefs or hopes are more likely to be remembered and those that do not tend to be forgotten, as anyone else. Like every other human, we confuse correlation with causation.

In fact, if there’s one thing I learned from watching my mother-in-law slowly die of breast cancer six years ago, it’s that being a doctor does not inoculate one from hanging on every observation hopefully, latching hopefully onto anything that seems like an improvement, even if ephemeral or not even real, and discounting anything that looks like a turn for the worse. And that was observing a disease that is my specialty. Dr. Howe is a radiologist; he’s not a neurologist or stroke expert. Let’s just put it this way: Emotional connection plus confirmation bias do not equal a witness any more reliable than average. There’s a reason why doctors generally do not treat loved ones. Emotional attachment affects judgment a lot more than we would like to admit. Emotional attachment also makes one prone to denial. I know this from personal experience too. Indeed, I could give you a specific example from when my mother-in-law’s cancer recurred in which denial led me to a very stupid conclusion about a finding, but I’m too embarrassed about it to admit the details to any but my closest family.

But let’s say that Howe really is as much improved as has been described, which, again, would be awesome. That still doesn’t really mean that it must have been the stem cells that were responsible, given that he had recently been hospitalized and had had a rocky course. Certainly everyone seems to be assuming that it was the stem cells. For instance, the physical therapist saw him “a few days after” the treatment. When did she see him last before that? When he was in bad shape at the end of November and in early December? The same question applies to the speech therapist. Again, correlation does not necessarily equal causation. For example, on December 3, the Detroit Free Press reported:

Son Mark Howe told the Free Press that Gordie Howe has had a hard time sleeping since being hospitalized Monday. “Anxiety from dementia does that to him,” Mark Howe wrote via text. “Change of surrounding makes his dementia worse as well.”

With this in mind, it’s hard for me not to ask: How much of Howe’s improvement was due to his having been home a few days after a hospitalization from December 1 to 3 followed by a trip to Mexico a few days later, and how much was due to the stem cell treatment? It’s really not possible to say, but news accounts before Fikes’ sure gave the impression that it just had to be the stem cells. Clearly Howe’s family believes that.

Stemedica and Novastem’s responses: Not reassuring

After Fikes’ story broke, I knew, in light of Stemedica and Novastem’s joint press release, that I had to update the story. Being a clinical trial guy, I was frustrated, however, that what I really wanted to know was not in either Dr. Howe’s press release, Novastem and Stemedica’s joint press release, or Mr. Fikes’ story. Here’s what I wanted to know:

- The protocol (or at least the schema for the protocol) for the Novastem stroke trial (or contact info for someone who could provide me this information), including: (a) the full list of inclusion and exclusion criteria for the trial; (b) the full list of primary and secondary endpoints being assessed in the trial; (c) the date of IRB review and final approval by Mexico’s regulatory equivalent of the FDA; and (d) any preclinical data supporting the trial that has been published in the peer-reviewed scientific literature.

- Why is the Novastem trial not registered with ClinicalTrials.gov or Mexico’s COFEPRIS registry, as I mentioned above?

- Do subjects in the Novastem trial pay for their treatment?

Regarding the last question, I was particularly curious about this issue in light of Novastem’s policies of cash on the barrelhead for treating basically anybody, as clearly delineated on its website, the statement in Fikes’ article that patients pay for this trial, and this statement from Dr. Howe:

Did Novastem treat our father for free? You betcha. They were thrilled and honored to treat a legend. Would you charge Gordie Howe for treating him? None of his doctors ever do. I certainly am not going to criticize them for being generous.

I find it fascinating that anyone would criticize Novastem for charging, or for not charging, for their services. They appear to have developed techniques and protocols which are safe and hold promise for countless individuals. My hat is off to them for the quality service they offer.

As sympathetic as I am to the Howe family, I’m sorry, but I reluctantly have to say that Murray Howe really should know better than this. If Gordie Howe was treated as part of a clinical trial, then Novastem should have treated him for free because if it is running a clinical trial it should treat everyone on the trial for free. That’s the way it’s done ethically. I realize that these stem cell treatments cost something like $20,000 to $30,000 a pop, but pharmaceutical companies testing new cancer drugs, for instance, not infrequently spend way more than that per patient on clinical trials. It’s the cost of drug development. Charging patients is also one of the big issues I’ve always had with Stanislaw Burzynski, for instance, charging patients to be on his clinical trials and justifying it by saying he’s not charging them for the experimental drug (antineoplastons) but rather a “case management fee.” In fact, I would argue that it’s even more unethical if a company doing a clinical trial charges some patients for the trial but doesn’t charge others, particularly if the reason it doesn’t charge a patient like Gordie Howe is because he is a sports celebrity. What about all the rest of the peons who aren’t famous? According to Fikes’ story, they get charged $20,000.

In trying to answer other questions, through a circuitous route I found myself in e-mail contact with Dr. Maynard Howe (no relation to Gordie Howe), the CEO of Stemedica. He was pleasant and more than eager to talk to me about Stemedica’s products, but, after some back-and-forth by e-mail, it became apparent to me that he couldn’t (or wouldn’t) provide me with any useful information about the Novastem clinical trial that I craved. Even though it had been he and Dave McGuigan, VP of Stemedica, who had reached out to the Howe family and facilitated Gordie Howe’s treatment in Tijuana, my impression was that he was basically washing his hands of the matter, referring me to Novastem for all questions because it wasn’t Stemedica’s trial. So I tried the Novastem general contact page and, ultimately, the e-mail address for the PI of this trial, Dr. Clemente Humberto Zuniga Gil, listed on his CV page on the Novastem website. I don’t know whether it was my e-mail through the general contact page, my direct e-mail to Dr. Gil, or, again in fairness, my previous communication with Maynard Howe having led him to contact Novastem that provoked a response, but on Saturday afternoon I received an e-mail response from the president of Novastem, Rafael Carrillo.

Mr. Carrillo was pleasant and accommodating. His e-mail responses struck me as very earnest and eager to explain his company’s position, stating that he was looking into registering Novastem’s clinical trial with ClinicalTrials.gov and COFEPRIS. He even sent me a PDF file containing a rather bare-bones clinical trial schema and tried to educate me about Mexican regulations governing clinical trials. Unfortunately, the information he gave me confirmed some of my misgivings about the trial and created others. For example, remember when I expressed puzzlement earlier in this post about what the clinic being registered with COFEPRIS meant? Well, he informed me that it meant:

As it states in our press release Clinica Santa Clarita is federally licensed to administer stem cell therapy. This means that the Mexican regulatory agency has authorized Clinica Santa Clarita and its doctors to apply stem cell therapy as the doctor sees fit. With the abundance of research across the globe and with the safety profile and high level of manufacturing Stemedica utilizes the Mexican authorities have felt it is justified to grant us a license to administer, as well as importing and banking stem cells. We treat all patients under IRB approved clinical trial protocols. We do this for two reasons, 1. We want to publish all our results. We want to share information. We believe that the more structured our data the easier it will be to publish. 2. We want to protect the patient. We have inclusion/exclusion criteria, informed consent, adverse event reporting, etc. At this point not everyone is a candidate for treatment. We want to make sure we are ethical in selecting patients for treatment.

So, in other words, the “federally licensed” part that confused me means that Clinica Santa Clarita can do pretty much anything it wants with stem cells, which is no doubt how it has been able to advertise its services and treat patients off-protocol in Tijuana. Learning this actually opened my eyes greatly as to how a weak regulatory environment in Mexico allows all sorts of dubious stem cell clinics to thrive there. In fairness, it is to Mr. Carrillo’s credit that he wants to do clinical trials and ultimately publish his company’s results. However, there is a problem—several, actually. First among them, as I pointed out before, the doctors with whom he is working appear not to have the requisite background in clinical trial design or stem cell science to produce a clinical trial that will generate useful data (more on that in a moment, when I discuss the clinical trial itself). He needs experienced clinical trialists, and I just don’t see any. Another problem is that he doesn’t seem to realize that in order to publish his clinical trial results in a decent journal, particularly one that follows the ICMJE guidelines, he had to have registered the trial with ClinicalTrials.gov or COFEPRIS before accruing patients. It’s too late now; Novastem’s already accrued one patient.

More problematic from an ethical standpoint is that Novastem charges patients to participate in its trials. In his e-mail, Mr. Carrillo tried to justify why Novastem charges patients for clinical trials:

Another issue you have brought up is payment. We are participating in patient funded research. We feel patient funded research is a viable option for both patients and doctors alike. On one hand we are not a billion dollar corporation that can fund all research, on the other hand we are following the examples of institutions such as the Mayo Clinic and MD Anderson Clinic who use this model. Patients know they have to pay. No promises are made to patients. It is very clear to all involved. We, and the IRB, feel there is enough evidence of safety and efficacy in the journals and doctor experience to proceed. Patients who choose to participate with us feel the same way. At no point do we hide this point.

In this particular trial the cost is around $30,000. Over half the cost is the cells alone, in addition to that we pay for the follow up work, the cost of patient recruitment, doctors fees, facility use fees, etc. Although $30,000 is a lot of money, to put it in perspective, it is also the cost of a knee replacement. Without being an expert in the field I believe that if this therapy proves to be effective, the cost benefit analysis will prove that getting the treatment is a good option. Also, like everything else that is new, with time and economies of scale price will go down substantially.

It was at this point that I heard disturbing echoes of Stanislaw Burzynski and his justification for charging patients tens—or even hundreds—of thousands of dollars to be on his clinical trials. It’s also a misunderstanding of how cancer centers like M.D. Anderson do things. For example, the M.D. Anderson website specifically addresses this issue, stating that “if you are participating in a clinical trial, the trial sponsor, embassy or your insurance company may cover some of the charges. Items paid by the clinical trial will be listed in your Charge Estimate Letter” and that “you or your insurance will be responsible for the charges not covered.” Generally, sponsors of the clinical trial have to cover the cost of the drug (or, in this case, biologic) and care that’s normally not part of standard of care but is related to the trial (such as additional scans or tests). Presumably, that’s how Stemedica’s trials work north of the border. Admittedly, this method leaves a big hole. Patients who don’t have health insurance will often have a huge difficulty paying for their care not related to the clinical trial and thus will have difficulties accessing cutting-edge clinical trials because they can’t pay for their own regular care. Yay, USA!

But what about the trial itself?

First, according to the document supplied to me, this trial underwent IRB approval on September 28. It is summarized thusly:

This is a pilot study in which a group of 30 volunteer subjects, with motor aphasia due to stroke will receive 90 x 106 of NSC intrathecally and an intravenous infusion of 90 x 106 of MSC. Leaving a window of 24 hours in between therapies. The subject follow up will continue for six months to verify safety, tolerance and to evaluate preliminary efficacy over speech, neurological function and quality of life.

This is roughly the same number of stem cells used in the Stemedica trial (one million per kg), but given intrathecal (into the cerebrospinal fluid) and intravenously. Here is a diagram of the study:

It’s a fairly basic design, with these inclusion criteria:

- Age 45 years or older

- Motor aphasia based on the neuropsychological evaluation.

- Evidence of ischemic lesion on MRI.

- Capacity to understand and sign the informed consent based on the neuropsychological evaluation.

- Commitment to continue with medical evaluations and follow up.

- Adequate functioning of diverse organs defined by a number of common laboratory values.

Regarding #4, it is known that Gordie Howe suffers from significant dementia. It is thus highly unlikely that he was able to understand and sign the informed consent, but I suppose I could be wrong about this, given that I don’t know the result of his neuropsychiatric evaluation. There’s no mention that the family can give consent for the patient; so I assume that, strictly following the protocol, they can’t. In fact, the exclusion criteria are:

- Global aphasia based on neuropsychological evaluation.

- Cognitive deterioration based on neuropsychological evaluation.

- History of cancer during the past 5 years.

- Subjects with oral steroids.

- Positive or reactive to HBV, HCV, VDRL or HIV.

- IMC ≥ 35.

- Pregnant women.

- Psychiatric abnormalities or abnormalities in the analysis based on the investigators criteria that might jeopardize the patient safety.

- History of alcohol or drug abuse and/ or smoking.

- Blood thinners seven days prior to the therapy.

This study is a not-unreasonable phase I study, although it lacks a dose escalation component, in which doses are ramped up in order to estimate the maximum safe and tolerated dose, and some important inclusion criteria (more later). Also, its endpoints aren’t well described. It’s also highly unlikely to detect any statistically-significant evidence of neurologic improvement, given that there is not a strong attempt to make the group being tested more homogeneous by, for instance, setting limits on various scores. I also wonder how Novastem defines the ability to understand and sign the informed consent. There’s also the issue of how cognitive deterioration is defined. Given the news reports, it could well be that Howe’s cognition was deteriorating, but, equally importantly, it could well be that he was getting a bit better. That’s where the Stemedica trial is actually better. It includes criteria requiring neurologic stability; without that, so soon after a stroke, it’s almost impossible to tell if improvement is likely due to the treatment or if it’s just improvement that was occurring as a normal part of recovery.

There’s another issue. In Fikes’ story, Dr. Murray Howe gives the following rationale for wanting to get his father on the Novastem trial ASAP, based on his having “one foot in the grave”:

However, the [Stemedica] trial requires participants to have had the stroke at least six months ago. So Howe wouldn’t qualify until late May.

Even more to the point, there was substantial doubt whether the elder Howe would survive for six months, or even until Christmas, said Murray Howe. Howe enjoys physical activity, and if unable to move he would lose his will to live.

I totally understand the Howe family’s desire to throw a “hail Mary” pass to try to save their dad (or at least make him more functional and improve his quality of life). My wife and I looked for the same thing when her mother was dying from metastatic breast cancer, which is why we had her evaluated by the phase I group at my cancer center. I’ve been on both sides. However, in designing and carrying out a clinical trial it’s critical to be very careful not to feed into the normal desires of family to do something. It’s equally important to remember that, no matter how much you repeat that “there are no guarantees” or that “this probably won’t work,” the family will latch on to the chance that it will work. That’s part of the reason why “patient-funded” clinical trials, as Mr. Carrillo describes them, are inherently prone to becoming exploitative. Just look at Stanislaw Burzynski, if you don’t believe me.

If Gordie Howe really was deteriorating so rapidly four weeks ago that there was substantial doubt about whether he would survive until the end of the year, then he probably should not have been a candidate for any clinical trial for stroke. Indeed, most clinical trials for chronic conditions like stroke (and even cancer) exclude patients who are deteriorating so rapidly because they are incredibly unlikely to benefit and they make it hard to detect a real benefit if there is one. Indeed, notice how the Stemedica trial has an inclusion criteria of “life expectancy greater than 12 months.” In marked contrast, there is no equivalent inclusion criterion in the Novastem trial, which is a huge gap.

Finally, the Novastem clinical trial is designed to examine the effects of stem cells on aphasia. A man who suffers from, if news reports are to be believed, significant dementia and, if Murray Howe’s account of his father’s condition in early December is accurate (and I have no reason to doubt it), Gordie Howe truly had “one foot in the grave” to the point where his son Murray didn’t think he could wait “even 30 days for a Compassionate IND treatment in the United States,” then he was not a good candidate for a clinical trial—any clinical trial, although an expanded use IND might still have been appropriate, particularly given that reports in early December from Howe’s other son Mark described him as “doing better overall than he was several weeks ago when he had a massive stroke” and that he had “improved enough in the past 24 hours to where we expect him to be out of the hospital and in his own bed at home before the night is over.”

Hope vs science vs exploitation

In clinical trials of new therapies, particularly for conditions that are either currently irreversible and result in a greatly diminished quality of life (like a stroke) or that will ultimately kill the patient (like certain cancers), it is always difficult to balance rigorous science versus hope and wanting to help as many patients as possible. After all, hope is part of why such patients enroll in clinical trials; that cannot be denied, and good clinical trialists are acutely aware of this. However, the ethical researcher tempers that hope and tries to keep it from being unrealistic. Moreover, as the example of my own experience with my mother-in-law’s stage IV breast cancer and the writings of Dr. Murray Howe about his father show, being a physician does not inoculate one from unrealistic hope and human cognitive shortcomings like confirmation bias. As physicians, we find this hard to admit to ourselves, but it’s true.

Similarly, it is potentially exploitative to require patients to pay to be on a clinical trial. That’s why legitimate trials in the US don’t require it, except in very uncommon, highly defined situations, and even then it is generally frowned upon. It is also highly unethical to treat patients on clinical trials differently based on their status. Ideally, none should pay to be on a trial, but if patients are being made to pay then it is, in my opinion, breathtakingly unethical to excuse one patient from paying just because he is a famous sports icon. It’s more unethical when that patient is used for publicity, as Gordie Howe has been. Such a special financial arrangement is inherently unfair to other subjects on the trial. Worse, it also smacks of paying a clinical trial subject for an endorsement and is thus potentially coercive. It is profoundly disappointing to me that neither Mr. Carrillo, Dr. Maynard Howe, nor Dr. Murray Howe appears to grasp this. Indeed, Murray Howe dismisses such concerns by writing that there were “no strings attached to [Stemedica and Novastem’s] offer” and that they “never have asked us to share Mr. Hockey’s amazing response.” Assuming that’s so, unfortunately the lack of explicit “strings attached” or explicit requests to publicly share Howe’s response don’t make the arrangement any less unethical or potentially coercive. Indeed, Howe points out that he shared his father’s response out of a sense of obligation, which is exactly what such arrangements engender and why they are unethical!

The saga of Gordie Howe’s stroke and his treatment at Novastem is a textbook example of why clinics like Clinica Santa Clarita are a major problem. Accountability is minimal to zero, and patients pay for experimental treatments. Unlike the case with Dr. Burzynski, I actually think that the leadership of Stemedica and Novastem believes in the Stemedica stem cell treatment. However, it is very difficult now, knowing what I know, not to walk away with the impression that Novastem was a tempting way for Stemedica to sidestep the regulations of the US and that Stemedica, its leadership apparently believing in a stem cell miracle, yielded to that temptation. Meanwhile, Mr. Carrillo seems to want to do the right thing but appears not to understand what the right thing is—or to have any clinical trialists working for him who can tell him what the right thing is.

Perhaps the saddest thing to me is that Dr. Murray Howe feels sorry for “anyone who finds this miracle ‘troubling.'” Presumably he means skeptics like Dr. Knoepfler and myself who have publicly questioned the news reports. I can assure Dr. Howe that I do not find Mr. Hockey’s progress and recovery “troubling.” No one, least of all myself, begrudges the Howe family hope. Indeed, I really do hope that Howe is doing better. I even hope it was the stem cells! After all, I’m not as young as I used to be. Cardiovascular disease runs in my family. I could easily find myself in Howe’s situation 20 or 30 years from now. I would love it if there was an effective treatment for brain damage due to stroke, and I do believe that stem cells have great potential to treat conditions that were previously untreatable.

Unfortunately, it’s everything else about his story that I find troubling, particularly how it was announced in the media, leading to numerous credulous reports portraying Stemedica’s stem cell treatments as some sort of miracle cure for Mr. Hockey and how Howe’s story as related by his family came across as very much of a piece with alternative medicine cancer cures and cures for other conditions. There is a right way and a wrong way to test treatments like this. Novastem looks as though it is taking the wrong way, whatever the motives of its president. Stemedica, too, is doing it the wrong way by trying to have it both ways, running legitimate clinical trials in the US while selling its product to be used however Novastem and Clinica Santa Clarita see fit. I feel obligated to point these things out not because I find Mr. Hockey’s reported recovery “troubling” but because not every stroke patient is Gordie Howe.