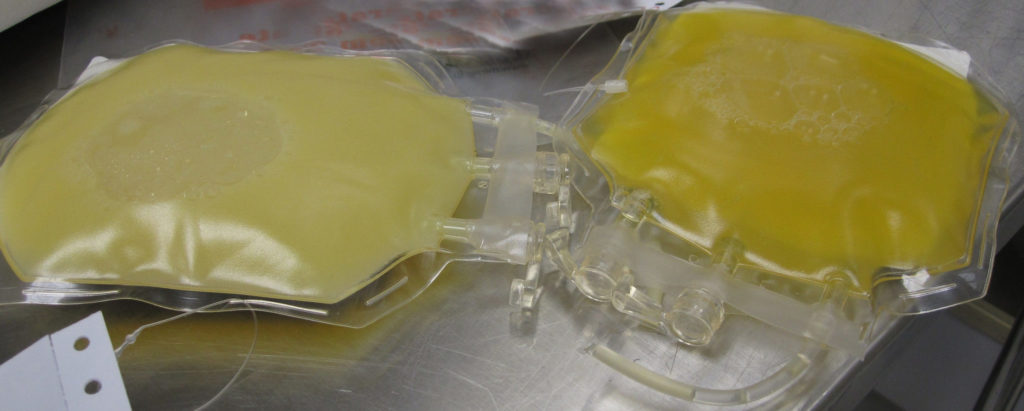

Two bags of fresh frozen plasma. The bag on the left was obtained from a patient with hypercholesterolemia, and is cloudy with undissolved cholesterol particles.

A recent article in The Guardian raised an interesting question. Is cholesterol denialism a valid form of skepticism or pseudoscience? Is there valid debate surrounding the benefit of cholesterol medication or is the evidence and the scientific consensus clearly on one side of the issue?

It is true that we argue about cholesterol far more than the other cardiovascular risk factors. It is hard today to find anyone who doubts the harmful effects of smoking, diabetes, hypertension or the lack of exercise. So why is there a cholesterol controversy but unanimity on other risk factors?

First off, we should acknowledge that there in fact has been a controversy on almost all these issues at some point. Ronald A. Fisher was famously resistant to the idea that cigarette smoking was harmful. Also, up until fairly recently, high blood pressure was seen as necessary to push blood through the narrowed arteries of people with atherosclerosis. Some of the more amusing quotes regarding high blood pressure are worth quoting verbatim:

Get it out of your heads, if possible, that high pressure is…the feature to treat.

– William Osler, 1912 address to Glasgow Southern Medical Society

Hypertension may be an important compensatory mechanism which should not be tampered with, even were it certain that we could control it.

– Dr. Paul Dudley White, 1937

The greatest danger to a man with high blood pressure lies in its discovery, because then some fool is certain to try and reduce it.

– JH Hay, British Medical Journal 1931

The fact is that controversies are not new. We simply tend to forget that they happened.

The early history of cholesterol research

The cholesterol controversy is a recent phenomenon because our understanding of cholesterol is relatively new. Diabetes has been described since antiquity and blood pressure measurements first occurred in the 18th century, but our understanding of cholesterol only dates to the beginning of the 20th century.

One of the earliest researchers in cholesterol was Nikolay Anichkov who in 1913 reported that rabbits fed pure cholesterol dissolved in sunflower oil developed atherosclerotic lesions, whereas the control rabbits fed just sunflower oil did not. At the time, this research had little impact and its importance was only recognized in retrospect. As Daniel Steinberg states:

If the full significance of his findings had been appreciated at the time, we might have saved more than 30 years in the long struggle to settle the cholesterol controversy and [Anichkov] might have won a Nobel Prize. Instead, his findings were largely rejected or at least not followed up. Serious research on the role of cholesterol in human atherosclerosis did not really get under way until the 1940s.

Laboratories that tried to reproduce Anichkov’s results using dogs or rats failed to show that a cholesterol rich diet caused atherosclerosis. This likely occurred because dogs and other carnivores handle cholesterol differently from rabbits and other herbivores This led many to dismiss Anichkov’s results on the grounds that rabbits were not a good a good model for human physiology and that his research was likely irrelevant to humans.

The criticism leveled against his research was not entirely unfounded. We have seen countless times how animal research does not translate into humans and to accept the “lipid hypothesis” based purely on Anichkov’s work would have been premature. It should have been an invitation for others to pursue this new line of inquiry. Eventually in the 1950s John Gofman would begin his research in lipoproteins and determine that there were different types of cholesterol. Today of course we acknowledge that low-density particles like LDL are atherogenic whereas high-density particles like HDL are not. Gofman demonstrated this in the 1956 Cooperative Study of Lipoproteins and Atherosclerosis although the distinction of LDL and HDL would only come later.

There was a fair bit of controversy surrounding the study at the time. The study actually had two discussion sections, one penned by Gofman’s group and the other by the other three collaborating laboratories in the study. The schism seems to have occurred over a technical point of cholesterol measurement with the others concluding that Gofman’s Atherogenic Index had “no advantage over the simpler measurement of cholesterol.” They also maintained, “lipoprotein measurements are so complex that it cannot be reasonably expected that they could be done reliably in hospital laboratories.” Fortunately, our technical mastery of cholesterol measurement has improved considerably and people were soon able to conduct large-scale epidemiologic studies to determine if measuring someone’s cholesterol provided insight into their cardiovascular risk.

The epidemiology studies

Despite the controversy that surrounded the Cooperative Study of Lipoproteins and Atherosclerosis, there was evidence that cholesterol (regardless how you measured it) was correlated with coronary disease. The work of Carl Muller studying patients with familial hypercholesterolemia was also largely supportive of this link. The work of Brown and Goldstein and their isolation of the LDL receptor would prove the genetic cause of this disease and win the Nobel Prize, but this work was still decades off. However, it could be argued, with some validity, that individuals with a genetic cause for their high cholesterol were not representative of the general population. Nevertheless, by the mid-1950s there was enough interest in this new potential risk factor that large-scale epidemiologic studies were launched.

The Seven Countries Study has certainly been one of the most notorious studies of the period and its originator, Ancel Keys, has become a popular target for attack. The main thrust of the attack is that he cherry picked the data in order to obfuscate the truth that saturated fats are unrelated to heart disease. The reality is slightly more nuanced and a detailed review of the Seven Countries Study highlighting its strengths and limitations can be found here for anyone who is interested. Suffice it to say, the main argument that can be leveled against the attempt to deny the role of cholesterol in heart disease is to point out that other studies have shown similar results.

Studies like the Ni-Hon-San study and the Honolulu Heart Study examined the rate of heart disease in Japanese men living in Japan, Hawaii and San Francisco. They found that compared to the men living in Japan, Japanese men who had migrated to Hawaii had higher cholesterol levels and higher rates of heart disease. Japanese men who migrated to San Francisco had still higher rates. The not-unreasonable conclusion was that the increase in heart disease was environmentally mediated and that as these Japanese men adopted the diet and lifestyle of their adopted country, their cardiovascular risk rose accordingly.

Finally, we cannot forget the impact of the Framingham Heart Study. Begun in 1948 and still ongoing, this project has provided many insights into the causes of heart diseases. It established that risk factors like cholesterol, hypertension, smoking, lack of exercise, and obesity all affected the risk of cardiovascular diseases. In fact, it coined the term “risk factor”.

Suffice it to say, whatever criticisms one wants to level against the Seven Countries Study, there was plenty of other data suggesting a link between cholesterol and heart diseases. Not unsurprisingly, researchers eventually resolved to try and do something about it.

The era of the diet studies

Although there was fairly good epidemiologic evidence linking cholesterol to heart disease risk, definitive proof would require demonstrating causation, not simply an association from population studies. Given that medications to lower cholesterol were still some years off, the only available tool at this point was a dietary intervention.

Importantly, many of these studies were not studies of a low fat diet. The dietary intervention under study was usually replacing a diet high in saturated fat (i.e. fat from animal sources) with polyunsaturated fats (i.e. fat from plant sources) with the goal of lowering blood cholesterol levels.

The Oslo Diet-Heart Study was one of the first such studies and recruited 412 men for 5 years of follow-up. Those randomized to the intervention group of vegetable oil did in fact see a drop in their cholesterol level as well as a decrease in cardiovascular mortality (79 vs. 94 deaths in the control group). The difference in all-cause mortality (101 vs. 108) was not statistically significant. The Wadsworth Veterans Administration Domiciliary Hospital Study was a similar trial. They had the advantage of a resident population that could be randomized to one dining hall or the other thereby ensuring good compliance with the study allocation. The 846 men in the study were studied for 5 years. Here too there was a reduction in major cardiovascular events (48 vs. 70 events in the control group). Another study in Finland randomized two mental health hospitals, assigning one to serve a diet high in saturated fat and the other to a diet of unsaturated fat. As part of its cross over design, after 6 years the hospital assignments were switched. It significantly included both men and women and demonstrated a reduction in cardiovascular mortality.

Unfortunately, not every study of the time was positive. A study done by the British Medical Research Council found no benefit to soya-bean oil. Serum cholesterol did fall in the intervention group, although the difference between intervention and control groups lessened with time, likely because of waning compliance. The number of cardiovascular events was lower in the intervention group (62 vs. 74) but the difference was not statistically significant. Another study testing corn oil found no significant change in the incidence of cardiovascular events, and one of the few studies to test an actual low fat diet found no benefit to cardiovascular disease.

All in all, the diet studies from this period suggested that lowering serum cholesterol levels could reduce cardiovascular events. However, someone could justifiably say that the evidence to date was inconsistent. In truth, the negative studies tended to be smaller and were probably underpowered. Also, the positive results tended to occur in studies where the change in serum cholesterol was greatest. For example, the low-fat diet study showed no cardiovascular benefit but also had little impact on cholesterol levels, which likely explains why it was negative. Still, the mixed bag of trials from this period instilled in many a doubt about the value of cholesterol lowering. Unfortunately, many failed to appreciate a subtle point. A dietary intervention can fail to produce a benefit (especially if compliance is poor). But the failure of dietary intervention does not mean that serum cholesterol is unrelated to cardiovascular risk.

The era of the early drug trials

By the late 1970’s, there were pronounced criticisms by some regarding dietary interventions for cholesterol lowering, regardless of whether those criticisms were deserved. But research into cholesterol metabolism was providing new medications that might potentially lower cholesterol levels and reduce cardiovascular risk.

The first candidate drug was clofibrate. In one of the first international randomized trials, 15,000 men with no history of heart disease were randomized to clofibrate or placebo. At 5 years there was a decrease in cholesterol and a 25% relative risk reduction in non-fatal infarcts. It was overall a positive study and gave further proof to the idea that lowering cholesterol prevents heart attacks. There were however two problems. There was no difference in cardiovascular mortality and all-cause mortality was slightly worse in the clofibrate group (162 vs. 127 deaths). This increased number of deaths was likely the result of random chance, but the idea that lowering your cholesterol could be dangerous has never really left us since.

The results of the Coronary Primary Prevention Trial were more encouraging. This double blind trial of cholestyramine demonstrated an 8.5% reduction in cholesterol, a 12.6% reduction in LDL and a 19% reduction in cardiovascular endpoints. In absolute terms, the reduction was from 8.6% to 7%. Once again, the trial showed that lowering cholesterol resulted in less cardiovascular events. Cardiovascular mortality was lower with cholestyramine too, but not statistically significant. There was, however, one bizarre finding to the trial. Although all-cause mortality was marginally lower in the cholestyramine group, there were a greater number of violent or accidental deaths (homicides, suicides, and car accidents) in those who got the drug (11 vs. 4 deaths).

These results once again caused some concern that cholesterol lowering was dangerous. Some worried that lowering cholesterol could impair brain function and lead to accidents or suicides (although how exactly it would make you the victim of a murder was never entirely made clear). The idea that cholesterol lowering can impair brain function keeps resurfacing. It is a common claim that statins can cause memory loss, even though the weight of the evidence suggests statins have no strong effect on memory one way or the other.

With two large trials done, in 1984 the NIH convened a Consensus Conference to review the evidence and establish guidelines. Their conclusions were that:

Elevated blood cholesterol level is a major cause of coronary artery disease. It has been established beyond a reasonable doubt that lowering definitely elevated blood cholesterol levels (specifically blood levels of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol) will reduce the risk of heart attacks due to coronary heart disease.

The media was less favorable in their critique. The Atlantic famously run a cover story on “The Cholesterol Myth” claiming, “lowering your cholesterol is next to impossible with diet, and often dangerous with drugs – and it won’t make you live any longer.”

There was of course something to this criticism. If not “impossible” to lower your cholesterol with diet, it is very difficult. In many of the more successful diet trials from the 1960’s, the research subjects were residents in hospitals or other institutions, which made controlling their diet fairly easy. Compliance in the community is of course harder. That it was dangerous to lower your cholesterol with drugs was perhaps overstating the point. That it won’t make you live any longer was technically true in that all-cause mortality was not statistically different. But it did prevent heart attacks and other cardiovascular events. Clearly they would improve quality of life if not quantity of life. Despite these nuances, skepticism about the benefit of lowering cholesterol remained fairly wide spread.

The statin era

When Akiro Endo developed the first statin, I don’t think anyone could have predicted how it would change the debate regarding cholesterol. Mevastatin, or compactin, never made it to market but similar drugs like simvastatin soon would. The Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study (4S) would demonstrate how effective statins would be at lowering cholesterol and reducing cardiovascular risk. If you compare the 4S study to the Coronary Primary Prevention Trial with cholestyramine mentioned above:

| CPPT trial 1984 | 4S trial 1994 | |

| Drug used | Cholestyramine | Simvastatin |

| Population | Only men | Men and women |

| Total cholesterol | 13.4% lower | 25% lower |

| LDL | 20% lower | 35% lower |

| Reduced CV events | 19% reduction | n/a |

| CV mortality | 24% lower | RR 0.58 (95%CI 0.46-0.73) |

| All cause mortality | n/a | RR 0.70 (95%CI 0.58-0.85) |

The 4S trial demonstrated not only greater cholesterol reductions but also greater reductions in cardiovascular and all-cause mortality. The benefits were also significant in women and patients over age 60.

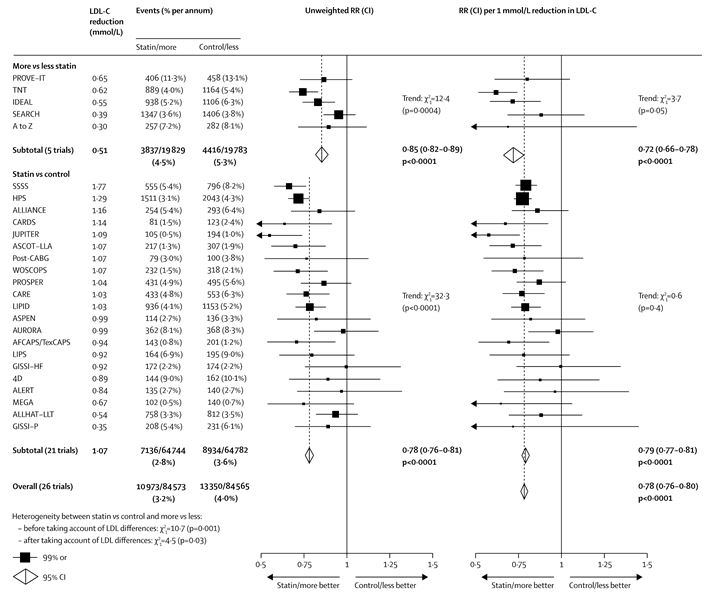

Twenty-six randomized trials later, we can draw some pretty firm conclusions about the benefits of statins. There are many meta-analyses summarizing the data on statins and some are better than others. Judging the value of a meta-analysis is difficult, although I do not hold with the old joke that the meta-analysis is to analysis, what meta-physics is to physics. There is value to a meta-analysis when done properly. A 2010 meta-analysis summarized the data and had the advantage of using individual patient data, which generally speaking greatly improves the value of the analysis. Also, their findings are largely in agreement with the US Preventive Services Task force. Their summary showed that LDL lowering with statins reduced not just heart attacks and strokes, but also all-cause mortality (RR 0·90, 95% CI 0·87–0·93; p<0·0001) for every 1.0 mmol/L reduction in LDL.

Figure 1 from: The effects of lowering LDL cholesterol with statin therapy in people at low risk of vascular disease: meta-analysis of individual data from 27 randomised trials. Lancet 2010; 376: 1670–81. Click to embiggen.

The controversy continues

The preponderance of the data from the statin trials was hard to reconcile if you wanted to maintain that cholesterol had no role in cardiovascular risk prevention. There was of course one possible position you could take. Maybe the benefit seen with statins had nothing to do with their ability to lower LDL cholesterol. Maybe statins had pleiotropic effects that acted independently of their cholesterol effects. For example, maybe statins had anti-inflammatory properties and this was why they prevented heart attacks.

There are two main counter-arguments against statin pleiotropy. The first is that when you re-examine the randomized trial data, the benefits to statin therapy appear quite linear. In other words, statins that lower LDL cholesterol the most have the greatest cardiovascular benefit. Our group found similar results. Using statistical techniques usually used in the field of genetic epidemiology, we were able to re-analyze the data from the statin trials and determine that pleiotropic effects were probably negligible. As I pithily pointed out to a friend of mine once our paper came out, we spent a great deal of time and effort trying to prove that cholesterol medications work by lowering your cholesterol.

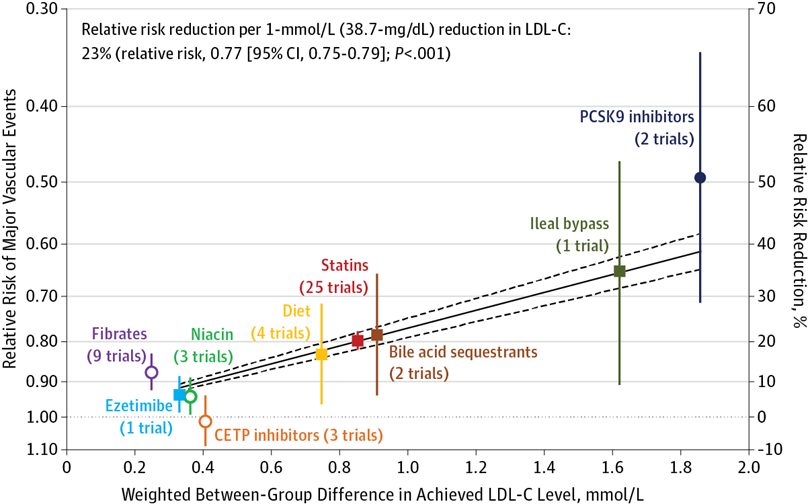

The second argument is perhaps more intuitively obvious to understand. After statins were developed two new classes of medications came onto the market. Ezetimibe blocks cholesterol absorption from the intestine and PCSK9 inhibitors act via the LDL receptor. Both medications lower LDL and both prevent cardiovascular events (although the benefit of ezetimibe is relatively small). Importantly though, they act via completely different mechanisms from statins. When statins were the only medications on the market, you could maybe entertain the idea that their benefit had nothing to do with cholesterol. But when you have multiple medications that lower cholesterol via different mechanisms all showing a consistent and proportional cardiovascular benefit, that argument becomes extremely untenable. The figure below demonstrates the point quite clearly. The cardiovascular benefit of different cholesterol lowering interventions is directly proportion to their ability to lower LDL.

Figure 3 from: Association Between Lowering LDL-C and Cardiovascular Risk Reduction Among Different Therapeutic Interventions A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis JAMA. 2016;316(12):1289-1297.

The common criticisms

It would be tempting to think that the wealth of data has ended the cholesterol controversy but it continues to this day. Common criticisms leveled against this hypothesis usually follow predictable patterns.

Argument 1: Carbs are the real enemy

The criticism against Ancel Keys, and the low fat diet in general, usually get extrapolated to mean that cholesterol is good for you. It is worth remembering that the diet trials of the 1960s were about substituting saturated animal fats with polyunsaturated vegetable fats. They were not tests of low-calorie vs. low fat diets.

Also, before going down the rabbit hole that is dietary epidemiology and the problems with interpreting the plethora of contradictory research on any subject regarding food, it is worth saying again the real issue is not the cholesterol in your diet but the cholesterol in your blood stream. Lifestyle factors like diet and exercise certainly have a role in cardiovascular risk reduction, but we now have medications that can accomplish degrees of cholesterol reduction substantially greater than what you can achieve with lifestyle changes alone. No one is debating that eating lots of candy is bad for you. What we are talking about here is treating hypercholesterolemia. That should be non-controversial treatment strategy.

Argument 2: Doctors over prescribe statins, lifestyle changes are best

The argument that we overprescribe statins and that people should just eat better is a fairly prevalent one. It is actually in direct opposition to Argument 1 and fails to acknowledge that the dietary trials of the 1960s were only modestly and inconsistently effective at lowering cholesterol and preventing heart attacks. Also, it is worth pointing out that lifestyle changes and medications are not mutually exclusive. You can do both simultaneous and you probably should.

Also, an increasing amount of evidence suggests that we should be pushing cholesterol levels even lower than we currently are. The concern that your cholesterol can be too low has been with us since the CPPT trial, including the concern that lowering your cholesterol could affect brain function. The data though suggests that lowering cholesterol below current targets of 1.8 mmol/L or 70 mg/dl provides a benefit with no trade-off in risk.

Argument 3: Statins have not been shown to be effective in women or the elderly

This is often repeated but not true. Early trials were done exclusively in men, and women have been historically under-represented in clinical trials. But starting with the 4S trial, thousands of women have been enrolled in statin trials and sub-group analyses show their effects to be similar to men. Similar sub-group analyses for people over age 75 also show a benefit.

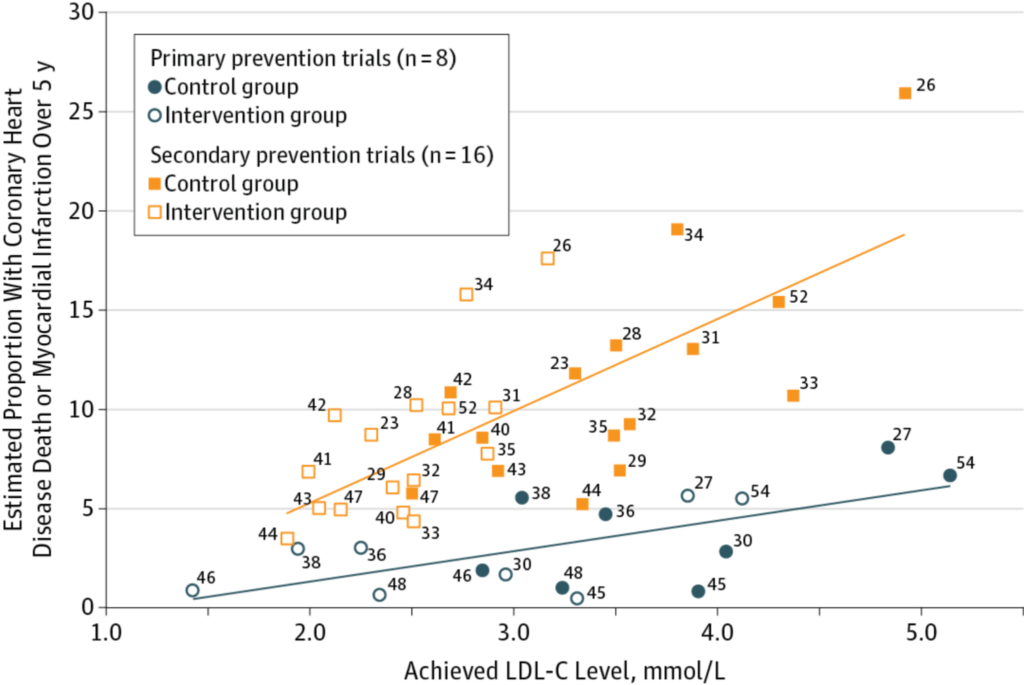

Argument 4: Statins don’t work for primary prevention

The US Preventive Services Task Force disagrees with this point. There have actually been many studies looking at statins in primary prevention (people who do not have established cardiovascular disease). The benefit in primary prevention is certainly less than in secondary prevention, but the benefit is still there.

Figure 4 from: Association Between Lowering LDL-C and Cardiovascular Risk Reduction Among Different Therapeutic Interventions A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis JAMA. 2016;316(12):1289-1297. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.13985

As the above graph shows, even in primary prevention, if you lower LDL, you lower cardiovascular risk. The magnitude of that benefit is smaller than in secondary prevention, and you might decide that benefit is too small to justify starting a new medication. As always, higher risk patients benefit most from medications. But the claim that statins have no benefit whatsoever is incorrect.

Argument 5: Statins are too expensive

Statins are generic now, which has largely eliminated the sting from that argument. Whether they are cost effective is a separate, but interesting, question. They certainly become more cost effective as prices drop. There is some debate about whether the benefit justifies the cost, although they are probably cost effective using the general definition of that term. It should be pointed out that cost effectiveness analyses depend quite a bit on the price of medications, and the cost assigned to side effects and outcomes. These can vary quite a bit from study-to-study and region-to-region, and different groups can come to different conclusions. An important point though, is that we are not debating whether cholesterol lowering works; we are debating whether it is worth the money.

Argument 6: Most people who have heart attacks have normal cholesterol

First off, as mentioned above, it is quite possible that “normal” cholesterol is much lower than we think it is. Blood pressures between 150 and 180mmHg, which now cause great stress and anxiety in patients and sometimes bring them to the emergency room, used to be considered as mild hypertension and treating it was of debatable value. Just as blood pressure targets were systematically adjusted downwards over the years, so have cholesterol targets.

Nevertheless there are some people who suggest that when you have a heart attack, having high cholesterol is protective. This observation is usually due to index event bias. Much like obesity can seem to be protective in heart failure, so too cholesterol can seem to be protective in patients after a heart attack. The unfortunate truth though is that neither is good for you. Anybody particularly interested in index event bias can read an editorial about it that we penned in the Canadian Journal of Cardiology.

Finally, if someone argues that most people with heart attacks have normal cholesterol, you can respond that most people with heart attacks are non-smokers, but smoking is still bad for you. The fact that a risk factor is rare doesn’t make it beneficial.

I also doubt the fact that most people with a heart attack have low cholesterol, but after searching I could not find good data one way or the other. Empirically though, my personal experience suggests this is untrue.

Argument 7: Statins have too many side effects

Statins do have side effects, like every other drug. We cannot deny that this is the case but we do not need to guard against hyperbole. People will sometimes claim that the rate of side effects with statins is nearly 20%, but this actually false and usually reflects a mis-quoting of the data. Complaints of myopathy are higher in observational studies than randomized trials and few randomized trials specifically looked at muscle-related outcomes. The one trial that did, STOMP, found statins did not decrease muscle strength or exercise performance but there were more complaints of muscle pain compared to placebo (9.3 vs. 4.6%). So, statins likely do cause some muscle problems although the risk of serious muscle or liver damage is very low. There is also appears to be a nocebo effect at play.

It is important to point out that being intolerant to statins does not imply that cholesterol is unimportant. When statins were the only feasible option the market for cholesterol lowering, the challenge of treating statin-intolerant patients was difficult. But now the problem is easier. A statin-intolerant patient, who cannot tolerate even a low dose or a different statin, can be switched to an alternative medication with a different mechanism of action. Over the years, much cholesterol denialism has been focused on statins specifically but with the advent of new and different drugs, this will become a much harder argument to carry forward. We should be cautious though, because new medications like PCSK9 are substantially more expensive than statins, and overstating the side effects of statins will only push more patients to more expensive medications. Also, there was a worrisome report that suggested that negative news stories about statins were associated with more statin discontinuation and a rise in heart attacks. While other factors likely also played a role, it should remind us that there are real world implications for patients who take these medications. Misstating the evidence has serious negative side effects.

Conclusion: Cholesterol is a risk factor for heart disease

Over the better part of a century, cholesterol has been examined as a possible risk factor for heart disease. There have been many criticisms along the way. Some were justified, some less so. Animal studies in rabbits cannot be applied to humans, diet studies are often ineffective, early drug trials were done exclusive in men, treatment did not translate into a mortality benefit, statins might have had a different mechanism of action, and statins are too expensive.

But all these criticisms belong to a different time. There are studies in humans. We have moved past diet studies for lowering cholesterol. Women are included in studies. There is a mortality benefit. Statins (and other medications) do work by lowering LDL. Statins are now generic. There are alternative to statins if you have side effects. The thing about the cholesterol controversy is that most of it has been settled.

Some issues remain. Maybe it is better to measure to non-HDL cholesterol or ApoB cholesterol instead of LDL cholesterol. But this is a subtle point, and finding a better way to measure something does not negate the underlying truth that high cholesterol increases the risk of heart disease.

There was a time when someone could be skeptical about the role of cholesterol in cardiac risk reduction. That time has now passed.