One of the common tropes of the anti-vaccine movement is that vaccine-preventable diseases are not all that bad. Perhaps the most direct manifestation of this is the self-published children’s book, Melanie’s Marvelous Measles, by Australian author and anti-vaccine activist Stephanie Messenger. Throughout the book Messenger claims that measles is nothing to be frightened of and in fact makes the body stronger.

This is an absurd and counterfactual claim, resulting, it seems, from a desire for a simple, clean narrative. People are born lawyers – we pick a side and defend it jealously. So, if you believe vaccines are dangerous you must also believe they are useless and the diseases they prevent benign. All the facts have to align in one direction.

The evidence strongly supports the conclusion that vaccines are safe (although not risk free), that they work (although are not 100% effective), and the diseases they prevent can sometimes cause serious complications.

Measles is Not Marvelous

Worldwide, measles is a leading cause of death in young children, and is the most preventable cause of death. The World Health Organization Statistics tell a very clear story:

In 2014, there were 114 900 measles deaths globally – about 314 deaths every day or 13 deaths every hour.

Measles vaccination resulted in a 79% drop in measles deaths between 2000 and 2014 worldwide.

In 2014, about 85% of the world’s children received one dose of measles vaccine by their first birthday through routine health services – up from 73% in 2000.

During 2000-2014, measles vaccination prevented an estimated 17.1 million deaths making measles vaccine one of the best buys in public health.

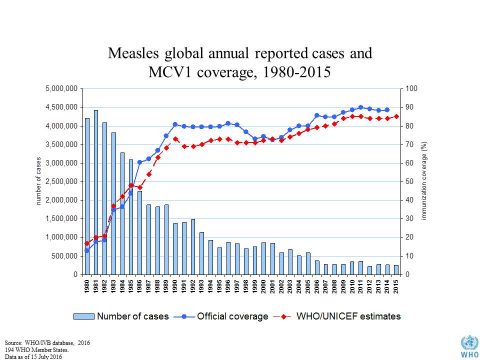

The MMR vaccine is also clearly effective, as the graph indicates. Deniers will likely point out that correlation does not prove causation, but it is certainly evidence for causation, and in this case very strong evidence. Around the world, MMR vaccination rates highly correlate with a decrease in measles cases and deaths.

We should not, however, focus only on deaths, because even children that survive may have serious complications. The two most common serious complications of measles are pneumonia and encephalitis, which is inflammation of the brain. About one in 20 children with measles develop pneumonia, which is the leading cause of death from measles.

Encephalitis is less common, affecting about one in 1,000 children with measles. This may also be fatal, but children who survive are likely to have epilepsy or intellectual impairment. Cases of measles encephalitis may be underestimated as there are reported cases of measles encephalitis without the characteristic rash, which means it will only be properly diagnosed if the virus is specifically looked for.

And these outcomes don’t even include possible indirect harms caused by the broader impact of measles on the immune system.

Subacute sclerosing panencephalitis

A serious late complication of measles infection is subacute sclerosing panencephalitis (SSPE). In some people with measles the virus is not eliminated, but rather travels to the brain where it sits dormant. Dormant viruses can reactivate in the future, often for reasons that are unclear. In the case of the measles virus, the virus can reactivate on average 7-10 years following the measles infection, causing SSPE, or severe brain inflammation. SSPE causes widespread damage to the brain. It usually starts subtly with changes in behavior, problems at school, difficulty walking, and muscle twitching. As the disease progresses it causes seizures of increasing frequency and severity and progressive dementia. Eventually the disease leads to coma and death, on average 1-2 years from onset of symptoms. The disease is universally fatal and without any cure.

In the developed world SSPE is a vanishing disease, specifically because of vaccinations against measles. World-wide the rate of SSPE is decreasing along with decreasing measles and increasing vaccination.

The risk of developing SSPE following measles has been estimated at about 1 in 100,000 children. However, this may be a huge underestimation.

A recent study, not yet published but presented at the infectious disease conference, IDWeek 2016, examines this. As reported in Scientific American:

But the new analysis suggests that kids who get the measles before age 5 have a one in 1,387 chance of developing SSPE, and kids who get the measles before age 1 have a one in 609 chance.

The authors looked for all cases of SSPE in California between 1998 and 2015, identifying 17 cases, resulting in the odds detailed above.

The data also reinforce the need for herd immunity. The risk of SSPE is greatest for children who contract measles prior to age one. However, the first dose of the MMR vaccine is not given until 12 months, which means that children less than one need to be protected from measles by herd immunity.

None of this, by the way, is marvelous.

Conclusion: The reality is, measles is extremely dangerous

While this study is just one piece of epidemiological data, it is a good opportunity to review the scientific reality of measles and the importance of vaccination.

In the case of measles we have a highly contagious virus that is a leading cause of death and disability in young children. Fortunately, it is also completely preventable with a simple and effective vaccine. As the WHO points out – this is one of the most cost effective and highest benefit-to-risk ratio health interventions that humans have devised. The world-wide vaccine campaign has saved an estimated 17.1 million children deaths from measles in the last 14 years.

Denial of these facts, and fear-mongering about vaccines, directly results in the death of children.