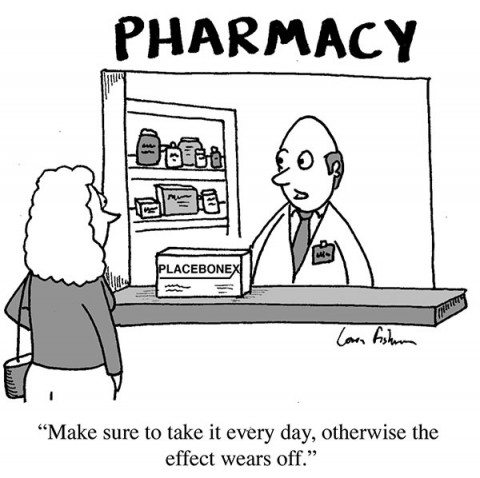

We frequently write about placebo effects here on Science-Based Medicine. The reason is simple. They are an important topic in medicine and, at least as importantly, understanding placebo effects is critical to understanding the exaggerated claims of advocates of “complementary and alternative medicine” (CAM), now more frequently called “integrative medicine” (i.e., integrating pseudoscience with science). Over the years, I (and, of course, others) have documented how CAM advocates have consistently moved the goalposts with respect to the efficacy of their pseudoscientific interventions. As larger and better-designed clinical trials have been done demonstrating that various CAM therapies without a basis in science—I’m distinguishing these from science-based modalities that have been co-opted and “rebranded” as CAM, such as exercise and nutrition—have no specific effects detectable above placebo effects, CAM advocates move the goalposts and claim that CAM works through the “power of placebo” and do their best to claim that “harnessing” that “power of placebo” is a justification to use their treatments. It turns out, however, that when placebo effects are examined rigorously there’s just not a lot of there there, so to speak. Results are underwhelming, and trying to “harness the power of placebo” without an intervention that actually impacts the pathophysiology of disease can even be dangerous. That’s not to say that learning to maximize placebo responses (whatever they are) while administering effective medical treatments isn’t important; rather, it’s to point out that, by themselves, placebo effects are not of much value.

Unfortunately, none of this has stopped what Steve Novella refers to as the “placebo narrative” from insinuating itself into lay discussions of medicine. That narrative proclaims in breathless terms (as Steve put it) the “surprising power of the placebo effect” without putting it into reasonable perspective or even really defining what is meant by “placebo effect.” First, as we have tried to explain time and time again here, there is no single “placebo effect.” There are placebo effects. Second, the only really correct reference to “the placebo response” or “placebo effect” is the outcome measured in the placebo arm of a clinical trial. The problem is that, all too often, discussions of placebo responses conflate the placebo effect measured in a clinical trial with all the other various placebo effects that add up to the response that is measured in that trial. Those effects include reporting biases, researcher biases, regression to the mean, conditioning, and many other components that contribute to what is measured in the outcome of a clinical trial. Another common misconception about placebo effects is that they are somehow “mind over matter,” that we can heal ourselves (or at least reduce our symptoms) through the power of will and mind. This is not true. Placebo effects are not the power of positive thinking.

Unfortunately, over the weekend as I was perusing the New York Times, I saw another article full of the flaws in understanding and argument discussed above, so much so that seeing it made me change my topic from one that I had planned to write about earlier. It’s by Jo Marchant and entitled “A Placebo Treatment for Pain“. You can tell right from the title that it’s going to promote the usual CAM tropes about placebos, and indeed it does. In fact, it reminds me of another article that Marchant wrote back in October that was inexplicably published in Nature, “Consider all the evidence on alternative therapies“.

Before the Nature piece, the name Jo Marchant had been vaguely familiar, but I didn’t really know who she was; I just remembered having heard the name before. At the time, I looked her up and found that she is a freelance journalist specializing in science and history. I also learned that she has written a book entitled Cure: A journey into the science of mind over body that is due to be released in just over a week. Just by reading the blurb, you can see where Marchant is coming from in her two articles:

Cure begins with a simple question: can our minds really heal our bodies?

It is a controversial subject. The idea of ‘healing thoughts’ was long-ago hijacked by new age gurus and spiritual healers. But as this compelling new book shows, serious scientific researchers from a range of fields are now uncovering evidence that our subjective thoughts, emotions and beliefs can have very real benefits for our health, from easing symptoms and influencing immune responses to reducing our risk of getting ill in the first place.

In Cure, the award-winning science writer Jo Marchant travels a wide terrain of ideas – from hypnosis to meditation, from placebos to positive visualisation – rescuing each from the realm of pseudoscience. Drawing on the very latest research Jo discusses the potential – and the limitations – of the mind’s ability to influence our health, and explains how readers can make use of the findings in their own lives.

Calling Harriet! Have I got a book for you to review! (I wonder if they’ll give us a review copy after this article, though.)

I could save Ms. Marchant the trouble and just answer her question with a simple no plus these three posts by me: Does thinking make it so? CAM placebo fantasy versus scientific reality, The rebranding of CAM as “harnessing the power of placebo,” and Placebo effects are not the “power of positive thinking” and leave it at that. But, as Han Solo once said, “Hey, it’s me.” So let’s dig in.

“Hey, It’s me.” Which means I’m about to go off on a several thousand word rant about pseudoscience. It’s what I do. Just like going off to do something incredibly dangerous and reckless is what Han Solo does.

Placebos: The mechanism of CAM?

The first thing I noticed about the NYT article is that, as opposed to using placebo effects as a rationale to “consider all the evidence on alternative therapies” (as if we at SBM haven’t been doing just that for eight years now), her NYT op-ed, “A Placebo Treatment for Pain“, uses the “crisis of painkiller addiction” as its jumping-off point and rationale to sell placebo effects explicitly as something that might be used to treat chronic pain. In essence, she buys into the claims by CAM advocates like Ted Kaptchuk that it’s possible to produce strong placebo effects without lying to patients, something that has not been demonstrated, certainly not by Kaptchuk, although not for lack of trying. In any case, looking in retrospect, Marchant’s Nature article sets up the argument made in her NYT article, the latter of which, in contrast, only briefly mentions alternative medicine.

One thing that’s clear examining Marchant’s output over the last couple of years is that she appears to believe that you can think yourself healthy, at least to some extent. Perhaps she admits that you can’t cure cancer with your mind, although she does seem to think that meditation can actually slow aging, citing Elizabeth Blackburn’s work, which has been ably deconstructed before right here in SBM. (I suppose I should be grateful that she didn’t invoke epigenetics and the mind’s supposed ability to dictate its gene expression, as some CAM apologists do.) In any case, as you will see Marchant’s article is a sterling example of what you do when you advocate therapies that don’t have any specific therapeutic effects above and beyond that of placeboes. You embrace placeboes as real medicine, and claim your quackery exerts its therapeutic effect through placebo.

For example, Marchant declares in her Nature article:

“Insane”, “a joke”, and “exactly the sort of thing the NHS should not be doing!” are a few of the Twitter responses to last week’s news that Britain’s Princess Alexandra Hospital NHS Trust wants to hire a reiki therapist for a hospital in Epping. On a salary of up to £22,236 (US$34,000) a year, the appointed person “will provide Reiki/Spiritual healing to patients to enable them to cope with the emotional, physical and spiritual issues of dealing with their cancer journey”.

Critics of the advert — and there are many — advocate instead what they call “evidence-based” approaches to health care. These critics should look again at the evidence — because it shows that to dismiss the benefits of alternative therapies is simplistic and misguided.

No. Just no. It’s not “simplistic,” although that’s a frequent simplistic trope used by fans of quackery to dismiss criticisms of said quackery based on science. Oh, they will say, in essence, “You silly English SBM kniggits reductionistic Western scientists, you! I fart in your general direction! You do not understand the deep complexities and interrelatedness of our woo. Now, go away, or I shall taunt you a second time!”

I exaggerate, of course, but not by much.

This seems to be the response of CAM apologists any time a skeptic arguing for SBM criticizes their argument that we should somehow “harness the power of placebo.”

Actually, British skeptics and advocates of science-based medicine have every right not to want their precious taxpayer funds wasted, funds that could and should be used to pay for treatments shown to be effective based on science, rather than for rank quackery like reiki. It’s particularly irritating to me that this specific ad was looking for a reiki practitioner to ply his or her quackery on cancer patients, particularly breast cancer patients.

Now, I know the British seem to have a soft spot for homeopathy. After all, there was an NHS-funded homeopathy hospital known as the Royal London Homeopathic Hospital, until a few years ago when the people who run it realized that (1) homeopathy is too easy to attack because it’s so obviously not based in science and (2) they needed to diversify their quackery and get hip to the latest lingo, which is to “integrate” quackery with science-based medicine, the better to give it the appearance of scientific validity. That’s why a few years ago the Royal London Homeopathic Hospital was reborn as the Royal London Hospital for Integrated Medicine. The other thing that Marchant seems utterly unconcerned about is that reiki is among the quackiest of quackeries. Indeed, whenever I would contemplate a ranking of quackery, I used to call homeopathy “The One Quackery to Rule Them All.” (It’s true, just search this blog for that phrase.) Lately, however, I’ve been wondering if that’s true. After all, reiki is basically faith healing that substitutes Eastern mystical claims that its practitioners can channel healing energy from “the universal source” through the practitioner into the patient. Substitute the word “God” for “universal source,” and you’ll see why I refer to reiki as faith healing.

So what’s quackier? Faith healing, or a treatment that claims that water “remembers” the healing substance that it’s been in contact with (conveniently forgetting all the nasty stuff it’s also been in contact with, like urine) and that diluting a substance makes it stronger. I don’t know, to be honest. It’s kind of like asking what stinks more, a sewer or a cesspit. I do know that, when you add all the other nonsense that goes along with reiki, like distance healing, reiki does indeed given homeopathy a run for its money as far as quackery goes.

Of course, Marchant is quick to point out after this that she doesn’t believe in all that mystical mumbo-jumbo. Oh, no. She’s into science, maaaan. Rather, she believes in what I just referred to, namely the power of the magical placebo:

Let’s be clear, I don’t buy into the pseudoscientific claims of reiki and spiritual healers. There is no evidence that they can tap into and manipulate human ‘energy fields’ to clear blockages and heal the body. Like many alternative therapies, these practices perform no better than placebos in clinical trials.

Well, that’s a relief. But… Yes, I can hear the “but…” coming, and so it does right away, instead of taking several paragraphs, as it would if the showrunners of The Walking Dead had been writing this article:

But that does not mean that such treatments have no distinct therapeutic value. To dismiss people’s complex psychological and physiological reactions to serious illness — and how it is treated — as mere placebo effects is not helpful.

Neuroscience studies show that placebo effects can trigger significant physiological responses that are often identical to those created by drugs, ranging from the release of dopamine in the brains of people with Parkinson’s disease to a rush of endorphins for those in pain.

And there you have it. Marchant buys wholeheartedly placebo myth. Sure, she doesn’t go off the deep end, the way that Robert Schiffman did when he cited placebo effects as proof that God exists, but she does buy into the myth. Indeed, she sounds very much like a homeopath who made similar arguments. Anyone remember Heidi Stevenson? Actually, on second thought, maybe not. Heidi Stevenson stated flat out that placebo effects cannot cure, as part of arguing that alternative medicine is more than placebo, while Marchant seems to be arguing, in essence, that placebo effects can cure in certain conditions. Well, not exactly, but close:

The standard ‘evidence-based’ argument is that this is irrelevant. Even if alternative therapies induce a biological response, sceptics argue, patients are still better off receiving trial-proven conventional treatments, because then they benefit from both a placebo effect and the active effect of the drug.

This logic misunderstands the nature of placebo effects. Not all placebos are the same, and alternative therapies can sometimes trigger larger responses than conventional ones do. For example, in one trial, fake acupuncture relieved pain more effectively than a fake pill (T. J. Kaptchuk et al. Br. Med. J. 332, 391–397; 2006); in another, it relieved symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome with fewer side effects than available drugs (T. J. Kaptchuk et al. Br. Med. J. 336, 999–1007; 2008). It is true that if a therapy cannot beat a fake version of itself in trials, it is not working as the therapist claims. But if it triggers a big enough placebo effect, it might still be the best treatment available.

Marchant is actually missing a part of the skeptic argument, which is that placebo effects do not affect “hard” outcomes. For instance, placebo effects have never been shown to increase survival in patients with cancer, (Yes, death is the “hardest” endpoint of all, as it’s (usually) rather indisputable whether a patient is dead or alive.) That is why placebo controls are rarely used in cancer clinical trials any more. Instead, we tend to compare experimental treatment versus standard-of-care or compare adding experimental treatments to the standard of care to the standard of care alone. In addition, placebo effects do not generally affect the physiology behind the disease process. A great example of this is a study of sham acupuncture versus albuterol inhaler in patients with asthma. The results showed that, yes, patients did feel better. They did feel less short of breath. However, the “hard outcome” as measured by spirometry showed absolutely no effect on lung function. So, basically patients felt better but weren’t actually better. In the case of asthma, this could lead to death, as a patient could have the false assurance that, because he doesn’t feel as short of breath, he must be doing better when he could be very close to full decompensation.

So what about the studies cited by Marchant? The first one was only a single-blinded study examining acupuncture and amitriptyline for arm pain versus their respective placebos from repetitive stress injury. The acupuncturists were not blinded to whether they were providing “real” or “sham” acupuncture. It also has an utterly unsurprising result: More invasive placebos, like sham acupuncture, have long been known to produce more placebo effect than less invasive placebos, like pills. This study in no way shows that “alternative therapies can “sometimes trigger larger responses than conventional ones do.” It just provides one more bit of evidence supporting the unremarkable conclusion that invasive interventions produce more placebo effects than non-invasive measures.

The second study was no better. It, too, was single blind, with practitioners not blinded to assignment. It, too, does not show what Marchant thinks it shows. In fact, the study abstract looked very, very familiar. So I searched and found a lovely deconstruction written when it first came out. The CliffsNotes version is that what this study really showed is the importance of practitioner-patient interaction in enhancing placebo effects. I mean, seriously. Did Marchant even read the same study I did? I went back, read the study again. I didn’t recognize her summary in the conclusion.

So, having demonstrated that she has been thoroughly taken in by alt-med propaganda, Marchant happily goes all-in advocating placebo medicine. Pointing out that people tend to look at alternative medicine for problems that don’t have a good treatment available in conventional medicine, she advocates this:

The benefits of therapies such as reiki and acupuncture go beyond what we normally think of as placebo effects, however. Alternative therapists do not get results just because they are particularly good at fooling people into thinking that they will get better. Many elements of the care they provide — from talking to touch — seem to have the power to relieve symptoms and even influence physical outcomes. These elements do not show up when therapies are compared against sham treatments, because they are present in both arms of a trial.

Such benefits can be indirect. For example, tackling patients’ anxiety during invasive procedures such as keyhole surgery can reduce the risk of dangerous fluctuations in heart rate. This results not only from the direct effects on physiology, but also probably from patients needing lower doses of sedatives and painkillers.

Conventional medicine, with its squeezed appointment times and overworked staff, often struggles to provide such human aspects of care. One answer is to hire alternative therapists.

No, no, no, no, a thousand times no! To expand on Ben Goldacre’s famous quip about how problems in the airline industry do not mean that flying carpets work, just because there are problems in medicine does not mean that we should hire quacks like reiki practitioners to fill in the gaps. If physicians and nurses do not have the time or training to provide the “human touch,” then the answer is to change the system so that they do have that time (hiring more science-based practitioners would be a start) and to train them so that they are better at it. The reason is simple, and it’s all the pseudoscientific baggage that comes along with alternative medical practice. It’s a problem that Marchant acknowledges as a “legitimate concern” only to dismiss that same concern thusly:

Critics say that this is dangerous quackery. Endorsing therapies that incorporate unscientific principles such as auras and energy fields encourages magical thinking, they argue, and undermines faith in conventional drugs and vaccines. That is a legitimate concern, but dismissing alternative approaches is not evidence-based either, and leaves patients in need.

Instead of rejecting such approaches wholesale, let’s learn from them. That means going beyond the simplistic practice of jettisoning anything that cannot beat placebo. We must tease out the real active ingredients of these therapies — things such as ritual, mental imagery, empathy, care and hope — so that we can learn how they work and find ways to incorporate them into patient care.

Marchant is actually attacking a rather massive straw man here. Yes, endorsing treatments incorporating unscientific principles does encourage magical thinking. That is true. However, the reason we oppose “integrating” such nonsensical therapies goes beyond just that. Such therapies are rejected because they don’t work. Yes, the criterion used to evaluate them is that horribly “simplistic” standard of doing better than placebo. It’s a single, science-based standard that we advocate, one that applies to potential medicines and treatments, wherever they come from, “conventional” drug development pathways or “alternative” medical traditions. There are only three kinds of medicine: Medicine that has been shown to work scientifically, medicine that hasn’t been shown to work scientifically, and medicine that has been shown not to work. Guess which two categories apply to the vast majority of alternative medicine, if not all of it? Yes, the latter two. Of course, alternative medicine that is shown scientifically to work ceases to be “alternative” and becomes just medicine. Unfortunately, the concept of “integrative medicine” is special pleading, a transparent attempt to bypass the step of scientific validation in going from “alternative” medicine to medicine.

But what about using placebos?

If there’s one thing about Marchant’s message, it’s that it’s consistent. Presumably it’s the same message in her book, given that these articles are clearly intended to promote her forthcoming book. So in her NYT op-ed, after relating the scope of the problem of opioid dependence and abuse, Marchant suggests a solution to the problem. Surprise! It’s very much the same solution she hinted at in her Nature article:

How do we tackle this crisis? We often hear about efforts to clamp down on abuse, for example by regulating pain clinics and monitoring prescription patterns. But these won’t dent the demand for opioids unless we can find better ways to treat the hundred million Americans said to suffer from chronic pain. Simply switching to other drugs isn’t the answer. Few new painkillers are being approved, and existing ones, like Motrin and Tylenol, come with their own risks when used long-term, and some appear to be less effective than we once thought.

Help might instead come from an unexpected corner: the placebo effect.

This phenomenon — in which someone feels better after receiving fake treatment — was once dismissed as an illusion. People who are ill often improve regardless of the treatment they receive. But neuroscientists are discovering that in some conditions, including pain, placebos create biological effects similar to those caused by drugs.

Which leads her to suggest:

Placebo effects in pain are so large, in fact, that drug manufacturers are finding it hard to beat them. Finding ways to minimize placebo effects in trials, for example by screening out those who are most susceptible, is now a big focus for research. But what if instead we seek to harness these effects? Placebos might ruin drug trials, but they also show us a new approach to treating pain.

Sigh. Placebo effects do not “ruin” clinical trials. Rather, they are arguably mostly an artifact of modern clinical trial design, in particular the close observation and reporting. Indeed, the Cochrane review on placebo effects for all interventions notes that placebo effects vary from large to non-existent, even in well-conducted clinical trials and that these variations were partly explained by variations in how trials were conducted, the type of placebo used, and whether patients were informed that the trial involved placebo. The review also noted that it is “difficult to distinguish patient-reported effects of placebo from biased reporting.” Overall, the authors did not find that placebo interventions had important clinical effects in general. Similarly, in 2001, an analysis of clinical trials published in the New England Journal of Medicine comparing placebo with no treatment found “little evidence that placebos have powerful clinical effects” and had “no significant effects on objective or binary outcomes.” Basically, the preponderance of science suggests that placebo effects are probably mostly illusory, artifacts of clinical study design. That’s why I am very hesitant to rely on them for treatment of any clinically significant symptoms and very skeptical of claims like Marchant’s that our minds can heal our bodies through the placebo effect and we should therefore use that effect, apparently even if it means accepting reiki.

Later in the NYT article, Marchant references a study from earlier this year about how placebo effects appeared to be increasing, at least in clinical trials performed in the US. Steve has covered the study and what it showed, concluding that it really raises more questions than it answers. In reality, the central question from that study is not whether it indicates that we should use placebos as treatments but rather whether clinical trials are showing less of a difference between treatment and placebo because they are becoming more rigorous (i.e., older studies produced more false positives) or because they are getting worse and producing more false negatives.

Marchant also brings up again the “honest placebo,” like the one Kaptchuk claimed in a study whose results he characterized as a “placebo without deception,” even though the information given patients stated that “placebo pills, something like sugar pills, have been shown in rigorous clinical testing to produce significant mind-body self-healing processes.” In this case, she referenced a study for migraine:

It is unethical to deceive patients by prescribing fake treatments, of course. But there is evidence that people with some conditions benefit even if they know they are taking placebos. In a 2014 study that followed 459 migraine attacks in 66 patients, honestly labeled placebos provided significantly more pain relief than no treatment, and were nearly half as effective as the painkiller Maxalt. (The study also found that a placebo labeled “placebo” was 60 percent as effective as Maxalt if it was labeled “placebo.” If the placebo was labeled “Maxalt,” it was again 60 percent as effective as the real drug under its real label.)

With placebo responses in pain so high — and the risks of drugs so severe — why not prescribe a course of “honest” placebos for those who wish to try it, before proceeding, if necessary, to an active drug?

I wrote about this very study when it was published. Let’s just say that it doesn’t really show what Marchant (and, truth be told, many science writers) thought that it showed. For instance, there was a bit of priming in the study literature implying—you guessed it!—the power of placebo:

Scripted Information Read to Participants. “You are invited to take part in a research study for the purpose of understanding the effects of repeated administration of Maxalt for the treatment of acute migraine attacks, and why placebo rates are so high in migraine therapy. Our first goal is to understand why Maxalt makes you pain-free in one attack but not in another. Our second goal is to understand why placebo pills can also make you pain-free. Our third goal is to understand why Maxalt works differently when given in double-blind study vs. real-life experience when you take it at home. These goals are scientifically important for developing new therapies for migraine.

As I said at the time and repeat for emphasis: “Our second goal is to understand why placebo pills can also make you pain-free.” Not to understand why placebo pills might be able to make you pain-free or could possibly make you pain free. “Can make you pain free.” To be fair, this isn’t quite as blatant as the Kaptchuk study, in which subjects were told that placeboes could produce “powerful mind-body effects” in the study information. On the other hand, mentioning that “placebo rates are so high in migraine therapy” primes the subjects to expect placeboes to work. Another big flaw in the study (explained in more detail in my post) is that the investigators failed to assess expectancy. In any case, while an intriguing study, it was hardly evidence that it is possible to induce placebo effects without at least some deception.

Why SBM objects to using placebos as primary treatment

Like so many others who have fallen under the spell of CAM, Marchant appears to misunderstand the reasons why advocates of science-based medicine are alarmed by the “integration” of pseudoscience and mystical thinking into medicine in the form of “integrative” medicine. She seems to think it’s just because we “medical skeptics” don’t like them. While it’s true that most of us have a distaste for the utter nonsense behind alternative medicine like homeopathy and reiki, our objection goes beyond mere disgust at what we perceive (correctly) as quackery. There is also the issue of prior plausibility and Bayesian thinking, in which the posterior plausibility that a “positive” result of a clinical trial is really indicative of an effect depends on the prior plausibility. To put it very simply, the lower the prior plausibility, the more likely seemingly “positive” results are real effects are “false positive” results. That is the key difference between evidence-based medicine and science-based medicine: SBM incorporates prior plausibility based on basic science considerations into its assessment of treatments. EBM, in essence, does not, which is why quackery like acupuncture, homeopathy, and even reiki can be touted by some as “evidence-based.”

Finally, contrary to Marchant’s implication otherwise, we already do “tease out the real active ingredients” of placebo effects. Indeed, several of the papers she cited were efforts to do just that! However, as virtually all proponents of “integrative medicine” do, whether they realize it or not, Marchant is advocating a classic false dichotomy: Embrace quackery or abandon patients. It’s a false dichotomy because we don’t have to abandon science and reason to avoid abandoning patients, and problems with the “human touch” in medicine can be don’t require embracing magic to solve.

It’s not as though we haven’t been making these same points again and again and again for as long as I can remember. The problem is that advocates of “integrating” quackery into medicine keep making the same fallacious arguments. Now Jo Marchant is doing the same thing. These same old pseudoscientific arguments regurgitated by her are no more compelling or impressive than they’ve ever been. Now, depending on how popular her book ends up being, we’re likely in for another round of the same ol’ same ol’.

Most importantly, contrary to Marchant’s view, it is not unscientific to reject alternative medicine, nor do critics do so because of their lack of sophistication leading them to embrace “simplistic” ideas. We understand alternative medicine all too well, clearly better than Jo Marchant, who could really use to read this article on integrative oncology. We also understand that, as study after study fails to find effects of various alternative medicine treatments above placebo effects, the narrative about “integrative medicine” is morphing to embrace placebo medicine. It’s what you do when what you have doesn’t have any specific therapeutic effects. You treat placebo effects as though they are some sort of magic, Secret-like way of “healing yourself.”

Unfortunately, contrary to the faith in placebo medicine exhibited by Marchant, Kaptchuk, and others, there is precious little evidence that placebos on their own have any significant clinical value. That’s not to say that it’s not worth studying placebo effects to determine if there are strategies that we can use to maximize the perceived effectiveness of interventions through practitioner-patient interactions (which are incredibly important). Indeed, we advocate studying just that. Just don’t expect these studies to show that using placebo medicine will in any way impact the toll of opioid addiction or chronic pain. That is a promise of CAM believers that is about as likely to be kept as I am to win the record-setting $1.3 billion Powerball jackpot Wednesday night.