A few years ago, an Ocala, Florida, pediatrician, as part of a routine visit, asked a patient’s mother whether she kept firearms in the home. She refused to answer, feeling the question constituted an invasion of her right to privacy. The pediatrician then terminated the relationship and told the mother she had 30 days to find a new doctor for her child. In another incident, a mother reported she was separated from her children while medical staff asked them whether their mother owned firearms. And, according to a Florida legislator, he was told to remove firearms from the home during an appointment with his daughter’s pediatrician.

A few years ago, an Ocala, Florida, pediatrician, as part of a routine visit, asked a patient’s mother whether she kept firearms in the home. She refused to answer, feeling the question constituted an invasion of her right to privacy. The pediatrician then terminated the relationship and told the mother she had 30 days to find a new doctor for her child. In another incident, a mother reported she was separated from her children while medical staff asked them whether their mother owned firearms. And, according to a Florida legislator, he was told to remove firearms from the home during an appointment with his daughter’s pediatrician.

Complaints to Florida legislators about these and similar incidents prompted the introduction of a bill that would have, among other things, criminalized any

verbal or written inquiry by a . . . physician, nurse, or other medical staff person regarding the ownership of a firearm by a patient or the family of a patient or the presence of a firearm in a private home . . .

As finally passed by the legislature and signed by Governor Rick Scott, the 2011 Firearm Owners Privacy Act subjects physicians to disciplinary action for making “verbal or written inquiry” into a patient’s firearm ownership when the physician does not “in good faith believe” such inquiries are “relevant to the patient’s medical care or safety of others.” The Act included amendments to the Florida Patient’s Bill of Rights and Responsibilities, adding similar provisions. (The Act also applies to health care facilities, but here we will discuss only its effect on physicians and their patients.) Physicians may not enter any information regarding firearm ownership into the patient’s medical record if they know this information is not “relevant to the patient’s medical care or safety, or the safety of others.” They may not “discriminate” against a patient “based solely on the patient’s Second Amendment right to own firearms or ammunition.” Finally, physicians must refrain from “unnecessarily harassing” a patient regarding firearm ownership during an examination.

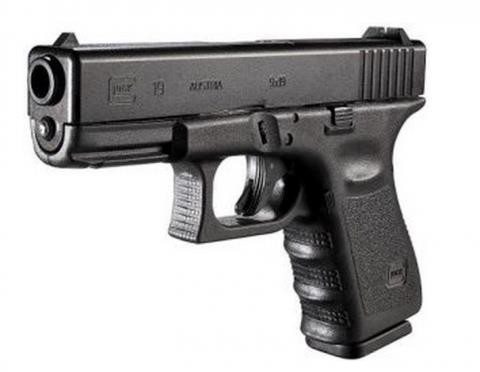

Shortly after Gov. Scott signed the Act into law, several physicians filed suit in federal district court challenging its constitutionality (Wollschlaeger v. Governor of Florida). The controversy was dubbed “Docs v. Glocks,” a term widely adopted by the media. Similar legislation has been introduced in at least 12 other states.

The Act, the physicians said, was an unconstitutional infringement on their First Amendment right to freedom of speech and was unconstitutionally vague because they were not fairly put on notice as to what they were expected to do to comply with the Act. (We’ll mostly focus here on the First Amendment issues.)

According to their complaint, the new law had caused them to change their practices in several ways. Previously, and in accordance with the American Medical Association’s policy guide’s suggestion that such questions were important to child safety and public health, these physicians had variously inquired about gun ownership as part of routine patient questionnaires, asked patients whether they owned firearms if there were other risk factors present (e.g., depression), and discussed firearms as part of routine preventive counseling. (The American Academy of Pediatrics, the American Academy of Family Physicians, and the American College of Physicians all recommend providing counseling and guidance on firearm safety as well.) All of these activities were viewed by the physicians as consistent with good medical practice.

After the Act, these physicians stopped asking firearm-related questions, in questionnaires or orally, either routinely or when the patient seemed upset by the inquiry, or stopped discussing firearm safety altogether, although some continued to do this by framing the inquiry in hypothetical terms not specific to the patient’s circumstances.

The U.S. District Court for the Southern District of Florida agreed with the physicians and prohibited enforcement of the law. The state appealed. In three separate opinions, all citing different grounds for its decision, a three-judge panel of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 11th Circuit upheld the Act over the vigorous dissent by one of the panel’s judges. We’ll return to those decisions shortly.

Government limitations on physicians’ speech

Over the past several years, federal appellate courts have addressed similar First Amendment challenges to laws that restrict physicians’ speaking to patients, either by forbidding them from discussing certain subjects or by compelling physicians to give patients legislatively-scripted information. In both situations, physicians may find the legislature’s requirements medically questionable. A key issue in these cases is the degree of deference the courts give to the states in deciding if the state’s restrictions violate the physician’s First Amendment right to free speech.

When the government tries to regulate the content of a person’s speech, as opposed to regulating the time or place where it occurs, the law is subject to strict scrutiny by the courts in determining its constitutionality. Under strict scrutiny, the court will find the government’s regulation invalid unless the state can demonstrate that it is justified by a compelling government interest and is narrowly drawn to serve that interest. This is the most demanding standard of review and courts rarely find content-based restrictions constitutional. Restrictions aimed at particular speakers or particular viewpoints are also highly disfavored by the courts.

Some types of speech are entitled to less protection, such as commerical speech, which is protected as long as it is truthful. Courts apply an intermediate level of scrutiny in these situations and content-related speech restrictions will be upheld only if the state can show the law directly advances a substantial government interest and that the law is drafted in a way that will achieve that interest.

Note that none of these categories of speech are actually mentioned in the First Amendment nor are the standards for court review. All of this is case law developed by the courts because, the U.S. Supreme Court decided long ago, the courts are the final authority in determining the constitutionality of government actions. Note also that the parameters of each level of scrutiny are stated in very broad terms, leaving plenty of room for interpretation. Of course, all of these cases present particular facts, and it would be impossible to fashion some bright-line test of constitutionality.

The appellate courts have been all over the board in deciding challenges to physician-patient communications, sometimes referred to more broadly as “professional speech.” The Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals upheld a California law banning so-called “sexual orientation conversion therapy” (SOCT) by finding that the therapy, although spoken, was simply a form of treatment, not unlike surgery. Thus, the therapy was really conduct, not speech at all, and therefore unprotected by the First Amendment. The Third Circuit also upheld a New Jersey law banning SOCT. The court decided the physician’s speech, in the form of therapy, was entitled to some level of First Amendment protection, but found that the ban was a permissible restriction on professional communication between a physician and patient, applying an intermediate scrutiny standard.

The Fourth Circuit also found intermediate scrutiny of professional speech appropriate and struck down a state law forcing physicians to display ultrasounds to patients seeking abortions, as well as to convey certain scripted information those patients. Conversely, the Fifth and Eighth Circuits upheld similar laws passed in Texas and South Dakota, respectively, reasoning that limitations on physician speech are part and parcel of the state’s power to regulate medicine and that restrictions are valid as long as they are “truthful, relevant and non-misleading,” applying the same standard used to review commercial advertising. The Texas law requires a physician to perform an ultrasound on a patient seeking an abortion so she can hear the fetal heartbeat and to explain the ultrasound’s results. Even though none of this is medically necessary, the court found it meets the “truthful, relevant and non-misleading” test. On the same grounds, the Eighth Circuit let stand a South Dakota law requiring physicians to tell a patient seeking abortion that she

has an existing relationship with that unborn human being and that the relationship enjoys protection under the United States Constitution . . . [and] that by having an abortion, her existing relationship and her existing constitutional rights with regards to that relationship will be terminated.

Again, medically unnecessary, but truthful, relevant and not misleading, and therefore constitutional.

I imagine your agreement, or lack thereof, with these decisions may be influenced by how you feel about gun control, abortion rights and SOPT. That is a natural response. However, any decision by an appellate court is binding precedent for all district courts within its circuit, and for that appellate court’s later decisions (unless overturned). Thus, it is important to keep in mind that the same rationale is going to apply to a later case where you may have an entirely different view of the issue under consideration.

The “Docs v. Glocks” case

Remarkably, the 11th Circuit, presented with the physicians’ challenge to Florida’s law, issued three separate opinions based on three different standards of review. (Again, this was a two-judge majority of a three-judge panel, over a vigorous dissent by the third judge.)

There was notable firepower on both sides of the argument in the form of amicus briefs. (These are briefs filed by non-parties who are interested in the outcome of the case.) On the physicians’ side is the AMA, the American Academy of Pediatrics, numerous other physician groups, the American Public Health Association, the ACLU, suicide-prevention groups and Children’s Healthcare is a Legal Duty. The American Bar Association is among these as well, because of the implications for state attempts to restrict another form of professional speech: attorney-client communications. The National Rifle Association is the heavy hitter on the other side, filing a brief in support of the state.

In the first opinion, Wollschlaeger v. Governor of Florida I, decided in 2014, the court found that, because the law restricts only speech by a physician in the context of the physician-patient relationship, but irrelevant (at least in the court’s view) to medical care, it was totally exempt from First Amendment protection. As the dissent pointed out, Florida’s ban silenced doctors on a single topic to prevent them from communicating a message unpopular with the legislature to their patients, thereby scoring a home run of sorts by putting aside not only the courts’ traditional hostility toward content-based restrictions on speech, but also toward restrictions aimed at particular speakers and particular viewpoints.

The physician-appellees petition for rehearing, and, in the second opinion, Wollschlaeger II, issued in July, 2015, the court held that the First Amendment was implicated after all. But, finding that the law survived the intermediate scrutiny standard required for restrictions on professional speech, the court upheld the law again.

The court then asked the parties to file new briefs discussing the implications of a recently-decided Supreme Court case. Although the case wasn’t directly on point, the court thought it might possibly require a less forgiving standard than intermediate scrutiny. Upon further consideration, but without deciding that strict scrutiny was indeed required, the court found that, if it were, the law’s restrictions on physician speech were nevertheless constitutional. This decision, Wollschlaeger III, was issued in December.

The physicians have filed a petition for rehearing by the full 11th Circuit. Whether the full court hears the case or not, the U.S. Supreme Court may eventually agree to consider the matter because of the conflicting decisions among the appellate courts.

Criticism of Wollschlaeger

One commentator, constitutional law professor Eugene Volokh, posting on the Volokh Conspiracy blog (carried by the Washington Post), disagrees with the court’s analysis, calling it “quite wrong.” This is of some significance because Volokh is an avid supporter of the Second Amendment. I imagine his is an early exemplar of what will become widespread criticism of the case from across the spectrum. (He also criticized the first two opinions, as did others in legal academia: Duke, Case Western, Harvard, Cardozo, and the University of Pittsburgh all have critical articles in their legal literature.)

Prof. Volokh provides a helpful summary of just how much the Docs v. Glocks law, as interpreted by the 11th Circuit, impinges on physician-patient communications.

- A doctor can’t ask all patients whether they own guns, “even if the doctor believes that this information would indeed be useful in giving general advice about safe gun storage, the supposed dangers of any gun ownership, and the like.”

- “[A]sking patients about gun ownership and entering that information into the medical record requires that the information be ‘relevant to the patient’s medical care or safety, or the safety of others.’ And, according to the panel majority, ‘relevant’ here [and in situations described below] means relevant based on ‘some particularized information about the individual patient, for example, that the patient is suicidal or has violent tendencies.'”

- Doctors can “turn away patients for refusing to answer questions about guns” so long as the questions are “relevant” but can’t “turn away patients for answering the questions with ‘yes, I own a gun.'”

- Doctors are banned “from unnecessarily harassing a patient about firearm ownership during an examination.” This means “that a doctor ‘should not disparage firearm-owning patients, and should not persist in attempting to speak to the patient about firearm ownership when the subject is not relevant . . . to medical care or safety.'”

So how are these restrictions justified by a compelling state interest narrowly tailored to its purpose? Volokh finds they aren’t. I agree.

The first “compelling” reason is protection of the Second Amendment right to keep and bear arms. But wait, as Prof. Volokh points out, stating the obvious, the Second Amendment, like the First, Third, Fourth, and so on, is a restriction on the government, not private individuals. And even if it did apply to private action, the physician can’t do anything to interfere with the patient’s constitutional right to keep and bear arms, no matter how annoying her questions might be.

The court’s rationale for this restriction on a private citizen’s speech is the “imbalance of power” between physician and patient. That, the court says, means the patient could be dissuaded from exercising his constitutional rights. But, as Prof. Volokh says, persuasion and dissuasion are exactly the sort of activity that is protected by the First Amendment. He finds equally unconvincing the court’s view that the restrictions are permissible because the patient is a “captive audience.”

And what’s next? He asks: Can the Florida legislature now prohibit questions that implicate other constitutionally protected rights?

“Are you sexually active?” “Are you using contraceptives?” “What kinds of contraceptives are you using?” “Do you want to have children at some point?” “Have you ever been pregnant?” “How many sexual partners have you had in the past year?” “Are you engaging in anal sex?” “How much television do your children watch?” “Do your children play violent videogames?”

Prof. Volokh concludes by echoing a point I made earlier. The 11th Circuit’s opinion, he says,

can apply to a wide range of situations where the government can claim some supposed tension (however indirect) between constitutional rights, some “power imbalance” between speaker and listener, or some “vulnerability” or “captivity” of the listener. If not reversed, it will set a dangerous precedent for speech far outside the gun debate.

Closer to the SBM home, my concern about legislative bodies making medical judgments is reinforced by state laws promoting politically-favored messages not necessarily consistent with evidence-based medical practice. (I do not include the SOCT bans in this category. There the legislature’s judgment was medically sound.) As we’ve discussed a number of times on SBM, legislators sometimes wander far outside the boundaries of science in making decisions affecting healthcare: Legislative Alchemy, the 21st Century Cures Act, non-medical vaccination exemptions, and “Right to Try” statutes. Physician questioning about gun ownership is, in my view, based on a reasonable judgment that discussing it is, at least arguably, a medically sound preventive medicine practice. Yet, the court, in requiring “relevancy” to a specific patient’s medical care based on a “‘some particularized information about the individual patient” effectively overrules the physician’s judgment. The same is true of state laws requiring physicians to make scripted speeches containing medically irrelevant information. Perhaps we need a constitutional “right to science” to protect the public against scientifically unsound legislative decisions.