The aptly-named “Not Appearing In This Post” turtle of South America.

I’m cheating. No, I’m recycling. ‘Tis the season to have to no time to get anything done. Since I know none of you pay attention to the blog of at the Society for Science-Based Medicine and I have no time with work and the holidays to come up with new material, I am going to collect and expand on the entries on acupuncture I wrote from SfSBM. Anything I write really is worth reading twice. I really need to make my multiple personality disorder work for me, but the Goth cowgirl persona is a luddite at best, so you are stuck with the over -extended ID doctor. Here goes.

Acupuncture: beer goggles or expensive wine?

Painting with a broad brush, I would say that acupuncture doesn’t work. By ‘work’ I would say that it has no effect that would change the underlying physiology or anatomy of the person receiving the acupuncture.

‘Works” is different from having an effect, even a beneficial effect. Positive interactions between a patient and a health care provider, even when offering a pseudo-medicine, will make some patients feel better about their disease. I compare these pseudo-medicines, like acupuncture, to beer goggles. They change perception but not reality.

While changing the perception of disease for the better is of benefit, it is just not ethical to base treatment on the lie that acupuncture ‘works’.

What happens with a process like acupuncture to alter patients’ perception? It doesn’t matter where the needles are placed or even if needles are used; twirled toothpicks are just as effective as ‘real’ acupuncture, what ever that may be. What matters most for efficacy is if the patient thinks they are getting acupuncture and if they believe acupuncture is effective. Then acupuncture will have a salubrious effect on subjective endpoints. That’s it. So what is going on?

Another hint as to the mechanism of acupuncture is found in “When pain is not only pain: Inserting needles into the body evokes distinct reward-related brain responses in the context of a treatment.”

In this study, 24 people received three identical stimuli: tactile, acupuncture, or pain stimuli. There were two groups to receive the three stimuli, an acupuncture treatment (AT) group and an acupuncture stimulation (AS) group. What differed is what they were told before the stimuli:

…participants in the AS group were primed to consider the acupuncture as a painful stimulus, whereas the participants in the AT group were told that the acupuncture was part of therapeutic treatment.

They had an fMRI (who doesn’t) and a questionnaire about their subjective experience:

Behavioral results generally revealed no differences between the AT and AS groups. The questionnaire results confirmed that there were no significant differences in expectancies, fear, or anticipation and subjective pain ratings related to needles being inserted into the body between patients in the AT and AS groups.

They found no analgesic effect in the acupuncture group. But there was a difference in the fMRI (for what that is worth):

We found that reward-related regions (specifically, the ventral striatum) of the brain were activated by acupuncture stimulation and that in response to painful simulation, activity in pain-processing regions(the SII and DLPFC) was decreased only when participants were told that acupuncture needles were a therapeutic tool.

And:

As greater activation of the ventral striatum is generally correlated with more expectations of pleasure and rewards, our results could be interpreted to suggest that acupuncture stimulation was associated with the expectation of a reward – possibly an analgesic effect – for patients experiencing acupuncture in the context of a treatment (AT group).

So depending on the context, people process the same stimulus differently. A needle that is thought to be for therapeutic acupuncture is different than the exact same needle thought to be used for painful stimulation.

Maybe. It is a small study and fMRI’s have issues as we know from dead salmon. But taken in the context of the literature pointing to the predominantly positive subjective effects of pseudo-medicines it is curious finding. Maybe not beer goggles; probably more like making wine taste better by giving it a higher price.

Acupuncture needs belief to work

Well not really acupuncture, at least not as the ancient Chinese did it. I do not think they had electricity to apply to the needles. But this was an interesting study, “Expectancy in Real and Sham Electroacupuncture: Does Believing Make It So?”

They took patients with joint pain due to aromatase inhibitors being used to treat breast cancer. The patients had either sham electroacupuncture (no current applied), electroacupuncture, or a wait-list control group, only about 20 in each group.

No surprise, those who had an intervention, be it sham or electoacupncture, had more pain relief than the wait-list control. An intervention, even if worthless, usually changes the subjective complaint for the better.

But here is where it gets interesting. They used the Acupuncture Expectancy Score (AES), a measure of how much the patient thought acupuncture would help their problem.

Over all, the higher the AES score, the better the pain response:

Each point increase in Baseline expectancy in the SA group is significantly associated with a greater percent pain reduction at Week 8 (regression coefficient = 7.9, SE= 2.8, P = .007).

In the sham group those with a high AES also had a better pain response. What is also interesting is that in the sham group there was no increase in the AES score over time and the decrease in the pain was constant.

Some in the electroacupuncture group increased their AES score with time and with a concomitant decrease in pain. Those who maintained a low AES scores had a pain response that was unchanged over time.

What they do not mention, which is a flaw, is whether blinding was effective. A little current across an acupuncture needle could easily be noticed by some of the patients and might have affected their perception of the intervention.

They say in the discussion:

Expecting a positive outcome (expectancy) at the beginning of the trial was associated with the response to SA. In contrast, patients who responded to EA had increased expectancy over the course of their acupuncture treatment as compared with nonresponders, suggesting that positive responses during the process of EA increased the expectations of positive outcomes. Our findings imply that distinct mechanisms underlie the apparently similar clinical effect of EA and SA. These findings have important implications for acupuncture and pain research as well as for clinical practice.

It may be the responders to electroacupuncture were the ones who noticed a tingling from the current and responded accordingly. Electroacupuncture is just a TENS unit tarted up with Traditional Chinese Pseudo-Medicine and this study has no implications for acupuncture except to reinforce its mechanism as an elaborate placebo.

I will mention here that I had always been taught that TENS was a legitimate form of pain relief. A quick review suggests TENS may be nothing but a placebo as well. Since more elaborate placebos yield better responses, it may be that those with the increased AES score were also those who knew they were getting TENS, a more elaborate placebo.

I wish they had tested for effectiveness of blinding, it would have been a nice addition to understanding what happened in evaluating two different placebos.

The authors say in the introduction that:

Although the response to SA has led skeptics to consider the acupuncture effect no more than placebo

And conclude with:

Our findings suggest that distinct mechanisms exist between SA and EA and challenge the notion that acupuncture is “all placebo.”

Methinks you doth protest too much. I see the study has variations of placebo effect, all placebo and nothing but placebo.

There were four kinds of beer goggles evaluated in this study; sham acupuncture with low or high AES and electroacupuncture with low or high AES with the added potential confounder that some in the high AES group may have known what they were getting TENS. The increasing AES and subsequent improved pain response may be no more than the effects of a more elaborate placebo with a positive feedback loop.

To my mind this is more data to support the notion that the effects of acupuncture, like the effects of all of CAM, is simply the patient deciding they are getting better, the pseudo-medical equivalent of kissing a boo boo to make it feel all better.

Animal torture

Psychology was, I admit, not my strong suit back in my pre-med days, the one class that ruined an otherwise-exemplary report card.

The only thing I took away from my psychology class was the concept of learned helplessness, perhaps because that describes a lot of medical education. To quote the ever-helpful Wikipedia:

Learned helplessness is a behaviour in which an organism forced to endure aversive, painful or otherwise unpleasant stimuli, becomes unable or unwilling to avoid subsequent encounters with those stimuli, even if they are escapable. Presumably, the organism has learned that it cannot control the situation and therefore does not take action to avoid the negative stimulus.

Put a dog in a box, shock it, and it gets depressed and stops looking for an escape. I think of learned helplessness when I see someone abusing an animal by jabbing it with useless needles (aka acupuncture). I know it is projection, but every time I see pictures of animals getting acupuncture, I see a depressed animal with learned helplessness.

Do any of these poor animals look happy with their acupuncture? Not to my eye.

The most recent animal to undergo well intentioned, and we know what the road to hell is paved with, torture, are Spanish owls.

1,200 injured owls are brought every year to a hospital in Spain where, for the last 6 years, then have been tortured with needles once a week for 10 weeks. Although they brag that 70% survive, I wonder if the added stress helped to kill the remaining 30%. Ten weeks of weekly torture cannot be good for wild owls. More likely they are improving in spite of the acupuncture rather than because of the acupuncture and given the lack of gloves with the punctures, I wonder how many died of inadvertent infections.

They give the usual nonsensical reason for using acupuncture and the usual denial of harm:

It stimulates self-curing mechanisms in the organism. It does not cause side-effects…

Don’t you think before you inflict pseudo-medicine on animals you would want to do a study not only to show efficacy, but to prove that you are not killing the animals with the added stress? I would. That is the nice things about animals: they are unable to complain about the numerous complications of acupuncture and so the practitioner can delude themselves as to the safety of their torture.

Poor owls. I am not a PETA kind of guy, but I am sympathetic to all the animals needlessly abused with completely worthless ‘therapeutic’ and experimental acupuncture.

After the fact rebuttal

I spent 5 days wandering the NE: Boston, Newport, Plymouth, back to Boston, Salem and then home. I was invited to give a talk on influenza and participate in a panel discussion about low back pain. The panel consisted predominantly of those who take care of backs for a living and I felt a bit like an Alzheimer’s patient who wandered into the room by mistake.

The panel was asked about using pseudo-medicines and as one of the militant members of the science-based medicine community, I gave my best three-minute summary on which SCAMs are useless. Then one of the members of the audience made a comment that, due to time constraints, I was unable to respond to.

So here is a paraphrase of the comment, and my response.

He started by saying he was a big believer in science-based medicine but…

But. Beware the but. That often means the speaker is about to endorse some bit of pseudo-medicine that he thinks deserves our consideration because, hey, I use it and it works for me. I was not disappointed.

He continued, mentioning that he has treated plantar fasciitis for years, usually with a single needle, often with only one or two treatments and it works more often than not.

This is, I suspect, the greatest reason that pseudo-medicines continue to thrive.

First is relying on experience as a valid criterion for deciding on a therapeutic intervention. Experience makes us better health care workers in so many mays it is virtually impossible for HCWs to recognize that the three most dangerous words in medicine are not “I lack insurance” but “In my experience.” They are a powerful meme for the speaker and totally useless to the listener.

Variations of the concept are found in the ideas that:

the plural of anecdote is anecdotes, not data

And the Richard Feynman quote:

The first principle is that you must not fool yourself–and you are the easiest person to fool. So you have to be very careful about that. After you’ve not fooled yourself, it’s easy not to fool other scientists. You just have to be honest in a conventional way after that.

The problem is that Dunning-Kruger appears to be the default mode for most health care workers, the

cognitive bias in which unskilled people make poor decisions and reach erroneous conclusions, but their incompetence denies them the metacognitive ability to recognize their mistakes.

So to my mind the speaker personified what may be the primary issue with pseudo-medicines in health care: the reliance on experience and the inability to recognize that it is useless.

He concluded with the usual chestnut about not throwing out the baby with the bath water. I hate that cliché.

Me? When it comes to pseudo-medicine I would throw out the baby, the bath water, the tub, the soap, the shampoo, the washcloth and the towel.

Lipstick on a pig?

I was wandering the Oxford English Dictionary and found a new definition for worthless: “Noun. A clinical efficacy trial with no blinding, no placebo, and only subjective endpoints derived from patient self-reporting.”

The OED is a stickler for examples of usage, so they pointed to “Effect of Perineal Self-Acupressure on Constipation: A Randomized Controlled Trial” in the Journal of General Internal Medicine. The study is out of UCLA, Yale and the Southwestern Law School !?!

They compared usual care or perineal acupressure for constipation. Perineal acupressure. Where did perineal acupuncture come from? I don’t know. The introduction has a discussion on the potential benefits of perineal massage and pressure, which can alter perineal muscles, increase rectal tone (wouldn’t that increase constipation?) and perhaps aid in defecation.

Then they jump to testing:

perineal self-acupressure, which consists of a patient repeatedly applying external pressure to the perineum.

Why acupressure? Why the acu? They make no mention of meridians or chi, which suits me fine.

There is an acupoint in the perineum in Traditional Chinese Pseudo-Medicine and it is not used for constipation, but rather it regulates yin:

- For yin deficient headaches

- Cold penis: a condition usually but not always associated with a lack of sexual desire

- Amenorrhoea and irregular menses

- Heat in the chest

- Pain in skin of the body, especially of abdomen and perineum

- Impotence, infertility and sterility, possibly frigidity

- Calms the mind: used for mania but can be used in less extreme conditions

The perineal points have nothing to do with constipation. So why the acu? Because tarting up a lousy study with pseudo-medicine gives the results more cachet and press than it deserves? That is my theory.

This is not an isolated example. A study adds ‘acu’ and now it gets far more attention than one that doesn’t. We saw this with “Dopamine mediates vagal modulation of the immune system by electroacupuncture.”

Virtually anything can get the acu designation if desired, and then more attention. I give antibiotics through acupuncture IV’s. Much cooler than regular IV’s. I can publish a study on my outcomes for cellulitis using acupuncture IV’s. I’ll tell half the patients they are getting acupuncture IV’s and half will get standard IV’s. I predict better satisfaction in the acupuncture IV cohort.

Maybe we jump on the bandwagon as well to get more press: Acu-Science-Acu-Based Acu-Medicine?

Bad studies lead to wasting money

It is amazing how quickly a single study can lead to an analysis as to whether an intervention should be used because it is cost effective.

There is no reason that acupuncture, a complicated magical ritual, should have any specific effect on any pathologic process. However, when I watch videos of acupuncture the process looks quite nice, except, of course, for the whole needles being stuck in the skin with zero attention to infection control. Relaxing in a caring and supportive environment cannot help but make people feel better, as long as they do not get hepatitis B or MRSA.

Like all interventions that do nothing, acupuncture is indicated for virtually everything (except as a form of contraception), at least by their proponents. Depression is on the list of processes that are not effectively treated by acupuncture.

After reviewing thirty, count ’em thirty, studies, with 2,812 patients, the last Cochrane Review:

found insufficient evidence to recommend the use of acupuncture for people with depression.

One would think that when 30 studies demonstrate an intervention with no basis in reality is useless, no self-respecting IRB could ethically approve the 31st study. Nope. In 2013 there was yet another study, “Acupuncture and Counselling for Depression in Primary Care: A Randomised Controlled Trial“, that demonstrated that counseling and acupuncture were associated with the same degree of reduction in depression at three months.

With no wait list and no sham acupuncture control there can be zero conclusions made about whether or not acupuncture per se (as opposed to the magical ritual) was of benefit or whether it was the natural history of the depression in that population.

The authors call it:

A pragmatic trial asks whether the intervention works under real-life conditions.

While I would call the trial a waste of time and money, whose methodological flaws ensure it proves nothing. Again, isn’t part of the ethical and practical considerations of IRB’s to avoid studies that are methodologically garbage? Guess not.

The article states no conflicts of interest, which I am sure is true technically i.e. financially, but when the lead author of a study suggesting magic helps depression is

previously trained as a practitioner of acupuncture and Chinese herbal medicine and subsequently founded the Northern College of Acupuncture

I remember the ever-so-wise words:

Conflicts of interest are very common in biomedical research, and typically they are inadequately and sparsely reported. Prejudice may not necessarily have financial roots. Scientists in a given field may be prejudiced purely because of their belief in a scientific theory or commitment to their own findings.

I will mention as an aside that PLOS does not publish author titles (Lac, ND, MD) in their papers. If a pseudo-medicine is being evaluated it would be nice to know which kind of pseudo-medical provider is doing the evaluation. As the old saying goes, “Go to Midas, get a muffler.”

So we have a preponderance of literature that demonstrates acupuncture is useless for depression and a fatally-flawed study that proposes an efficacy that doesn’t exist. What to do next? Not go to Disneyland.

You are a proponent of acupuncture. You have just finished a methodologically-horrible study that you can spin into demonstrating acupuncture is helpful for depression despite a vast contradictory literature. You note that:

Acupuncture is rarely provided within the UK’s mental health service or primary care, but private provision of acupuncture for depression is not uncommon.

Although what constitutes “not uncommon” from the reference is vague. In a table, 7% of providers use acupuncture for “psychological” disorders and the only mention of depression in the text is:

Anxiety, stress and depression were the three most prevalent psychological complaints and more commonly treated by independent acupuncturists.

In what looks like a manipulation of PLOS as part of a marketing program to increase the use of acupuncture in England, most of the same authors of the original paper hired an economist who found that, hey, acupuncture is cost effective.

If I had a conspiratorial bent, I would point to this as proof that the medical literature is being manipulated to further the financial gain of Big Pseudo-Medicine.

But it is not.

Just another sad example of the failure of peer review when applied to pseudo-medicine.

Bad infection control

In a prior entry I have mentioned my visual Googlewhack: I could find only one picture of gloves being used during acupuncture, and it was not being performed by an acupuncturist but a physical therapist doing dry needling.

I have also discussed the recalcitrance to basic infection control that informs the practice of acupuncture. It gives me the willies to watch acupuncture videos. It often looks as if they are trying to spread contagion with their technique.

Up north in British Columbia an acupuncture clinic was closed because of poor

infection prevention and control standards (that) poses a health hazard to clients.

That defines all the acupuncture I have witnessed.

Based on the investigation of the centre, we are alerting clients of Ms. Hu that they may be at increased risk of exposure to blood-borne infections that can be transmitted by improper and unsanitary acupuncture techniques.

The article alludes to acupuncture as the source of infections as well as:

other treatments involving blood or bodily fluids.

What was going on in the clinic?

How many people were exposed is not certain as:

Murti said Hu did not keep proper records, and it’s difficult to know how many people might have been affected.

But it is more than 1,000 people. Take that, Typhoid Mary. The health department is recommending testing by clients for blood-borne pathogens. Normally I would worry about HIV and Hepatitis B and C, but evidently Hu had even worse technique than I would have thought possible.

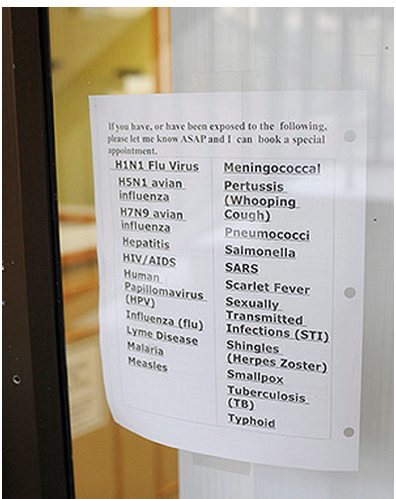

On her door is a list of diseases for which she wants her clients to contact her if they have been exposed to or currently have so she can make a special appointment.

The diseases include smallpox. Smallpox.

Yes, if you have or have been exposed to smallpox, most certainly see Hu for acupuncture, or perhaps other treatments involving blood or bodily fluids.

This list is a further suggestion that infection control is not well understood in the acupuncture world.

Cupping

We only have one big time professional sports team in Portland, the Trailblazers. No football or baseball. We do have professional soccer, but that doesn’t really count. In Portland the Blazers rule.

I had long thought cupping in athletics was a protective device to prevent groin injuries, although it is evidently voluntary in the NBA, as some have learned to their discomfort.

I think protective cupping would be a good idea. Therapeutic? Not so much. Evidently promoted by their Director of Player Health and Performance, cupping is a form of pseudo-scientific nonsense that is being used by the Blazers. I have discussed one form, moxibustion, before. Like most pseudo-medicine, it is an elaborate placebo with no real effects on real disease.

Its alleged mechanism of action is:

the idea is the suction draws fluid out of the area, Kaman explained, allowing tissues to heal more quickly.

And is not based on known processes. It is more akin to the wet sock treatment for stuffy nose, divorced from anatomy and physiology.

I am not surprised the Blazers are using it, since athletes often use pseudo-science. I suspect golfers lead the list. I still had to laugh at one quote:

“It’s scientific stuff,” Kaman said. “I could sit here and talk to you about it, but you wouldn’t know what I was talking about. I’m not calling you dumb it’s just a mixture of Western and Eastern medicines and some people think it works, some people don’t.

It is not scientific stuff, it is pseudo-scientific stuff. That is why no one understands what you are talking about. The theory and practice behind cupping is gibberish. Those who think cupping does not work are probably those who understand reality. As one meta-analysis said:

Although RCTs provide a higher quality of evidence, we included non-RCTs in this study because the limited number of RCTs did not provide convincing evidence.

Demonstrating the usual results of alternative medical studies: it only has effects when the studies are poorly done. The most unreliable form of evidence is the anecdote:

“I find it works pretty good,” Kaman said and “It works,” Batum said.

Well, it doesn’t in any well done study. Any positive results are due to placebo effects, the medical beer goggles.

I wonder if the Blazers will suggest giant magnets (3:52 mark) next for player injuries?