There are certain topics in Science-Based Medicine (or, in this case, considering the difference between SBM and quackery) that keep recurring over and over. One of these, which is of particular interest to me because I am a cancer surgeon specializing in breast cancer, is the issue of alternative medicine use for cancer therapy. Yesterday, I posted a link to an interview that I did for Uprising Radio that aired on KPFK 90.7 Los Angeles. My original intent was to do a followup post about how that interview came about and to discuss the Gerson therapy, a particularly pernicious and persistent form of quackery. However, it occurred to me as I began to write the article that it would be better to wait a week. The reason is that part of how this interview came about involved three movies, one of which I’ve seen and reviewed before, two of which I have not. In other words, there appears to be a concerted effort to promote the Gerson therapy more than ever before, and it seems to be bearing fruit. In order to give you, our readers, the best discussion possible, I felt it was essential to watch the other two movies. So discussion of the Gerson protocol will have to wait a week or two.

In the meantime, there’s something else that’s been eating me. Whether it’s confirmation bias or something else, whenever something’s been bugging me it’s usually not long before I find a paper or online source to discuss it. In this case, it’s the issue of why scientific studies are reported so badly in the press. It’s a common theme, one that’s popped upon SBM time and time again. Why are medical and scientific studies reported so badly in the lay press? Some would argue that it has something to do with the decline of old-fashioned dead tree media. With content all moving online and newspapers, magazines, and other media are struggling to find a way to provide content (which Internet users have come to expect to be free online) and still make a profit. The result has been the decline of specialized journalists, such as science and medical writers. That’s too easy of an answer, though. As is usually the case, things are a bit more complicated. More importantly, we in academia need to take our share of the blame. A few months ago, Lisa Schwartz and colleagues (the same Lisa Schwartz who with Steven Woloshin at Dartmouth University co-authored an editorial criticizing the Susan G. Komen Foundation for having used an inappropriate measure in one of its ads) actually attempted to look at how much we as an academic community might be responsible for bad reporting of new scientific findings by examining the relationship between the quality of press releases issued by medical journals to describe research findings by their physicians and scientists and the subsequent media reports of those very same findings. The CliffsNotes version of their findings is that we have a problem in academia, and our hands are not entirely clean of the taint of misleading and exaggerated reporting. The version as reported by Schwartz et al in their article published in BMJ entitled Influence of medical journal press releases on the quality of associated newspaper coverage: retrospective cohort study. It’s an article I can’t believe I missed when it came out earlier this year.

Until fairly recently (i.e., since I first started blogging nearly eight years ago), I didn’t pay much attention to press releases from medical journals and universities promoting published research to the media. If anything, the very existence of medical journal press releases about such studies puzzled me, striking me as unnecessary and unseemly self-promotion. (Yes, I was that naive, as amazing as it sounds to me now.) In fact, although I could sort of understand why universities would issue press releases when one of their investigators published a paper that might be of high interest or that appeared in a high impact journal, I wondered why on earth journals would even bother. After all, the quality and impact of science shouldn’t depend upon how many news stories are published about it in the lay press, should it? However, back in the late 1990s, research from investigators in Spain found that journal press releases work; journal press releases are associated with subsequent publication of news stories about the journal article(s) featured in the press release. Other studies suggest the same effect, although a subsequent study suggested that it’s not entirely clear whether this is correlation or causation. The reason is that journal press releases tend to be associated with “medical information that is topical, stratifies risk based on demographic and lifestyle variables, and has lifestyle rather than medical implications.” The authors concluded that medical journals “issue press releases for articles that possess the characteristics journalists are looking for, thereby further highlighting their importance.” Although I can’t prove it, intuitively this rings true, and it’s a finding that is reinforced by a survey of science and health journalists, who reported the “potential for public impact” (which studies that stratifies risk based on demographic and lifestyle variables almost always have) and “new information or development” as their major criteria for newsworthiness, followed by the “ability to provide a human angle” and “ability to provide a local angle.”

It’s hard not to note that these characteristics are pretty much completely unrelated to scientific rigor or importance.

Whatever criteria journals use to choose specific articles to issue press releases about and how large the effect journal and university press releases have on whether the media pick up on a study and report it, there’s a paucity of research out there that looks at how journal press releases influence the actual quality of the reporting on the articles touted by the journals. Therein lies the value of Schwartz et al, because it suggests that we as an academic community are at least as much to blame as reporters and the media companies for which they work. A surgery attending under whom I trained back in the early 1990s used to have a most apt saying whenever we had a patient transferred in: What they tell you the patient has and what the patient actually has are related only by coincidence. In the case of press releases, it sometimes seems that what the press release says and what the study says are related only by coincidence. As a result, since many news articles are based largely on the press release, that means that what the news reports of a study say and what the study itself says are often related only by coincidence.

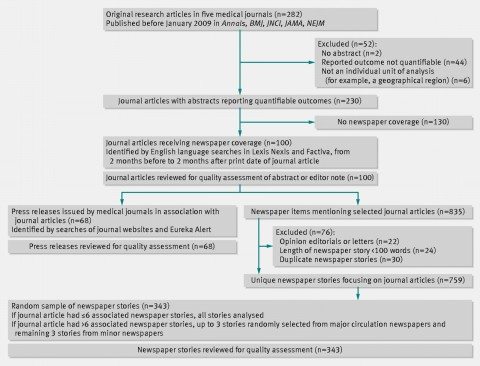

What Schwartz et al did was to review consecutive issues (going backwards from January 2009) of five major medical journals (Annals of Internal Medicine, BMJ, Journal of the National Cancer Institute, JAMA, and New England Journal of Medicine) to identify the first 100 original research articles with quantifiable outcomes and that had generated any newspaper coverage. These journals were chosen because their articles frequently receive news coverage but they have widely differing editorial practices. For instance, Annals and JNCI routinely include editor notes and editorials highlighting the significance and limitations of the studies featured, while the other journals do not. The NEJM doesn’t issue press releases. Here is how they chose their articles and press releases to study:

Their methodology is described further:

To rate newspaper stories on how they quantified results, we included only journal articles with straightforward quantifiable outcomes (that is, we excluded qualitative studies, case reports, biological mechanism studies, and studies not using an individual unit of analysis). To identify associated newspaper stories, we searched Lexis Nexis and Factiva (news article databases) for stories that included the medical journal name (the time frame for the search extended from two months before the journal article’s print date, to two months after).

The authors then did content analysis on the press releases and the news stories using the following criteria:

- Basic study facts. These include factors such as study size, funding source(s), identification of randomized trials, longitudinal study time frames, survey response rates, and accurate description (compared with the abstract) of study exposure and outcome.

- Main result. This included asking several questions, including: “Was the main result quantified? If so, was it quantified with any absolute risks (including proportions, means, or medians)? Were numbers used correctly (for example, did the numbers reported correspond to those in the abstract in terms of magnitude and time frame, or were odds or odds ratios misinterpreted as risks or risk ratios? The odds ratio issue was included under the category of numbers used correctly rather than as a separate measure.”

- Harms. These included questions such as (for studies of interventions claiming to be beneficial): Were harms mentioned (or a statement asserting there were no harms)? Were harms quantified? If so, were they quantified with any absolute risks?

- Study limitations. The authors asked if major limitations of the study were correctly described (or described at all) and considered “limitations noted in either the journal abstract or editor note, or on a design specific list that we created (web appendix) that includes limitations inherent in various study designs: small study size, inferences about causation, selection bias, representativeness of sample, confounding, clinical relevance of surrogate outcomes, clinical meaning of scores or surrogate outcomes, hypothetical nature of decision models, applicability of animal studies to humans, clinical relevance of gene association studies, uncontrolled studies, studies stopped early because of benefit, and multifactorial dietary or behavioural interventions.”

So what were the findings? To those of us in the science/medicine blogging biz, the findings are depressing but not surprising. For instance, although nearly all stories reported the exposure and outcome accurately, most stories were missing critically important information. For instance, only 23% quantified the main result using absolute risks (which actually surprised me; I would have guess the number to be lower, but perhaps there was a sampling difference between what I read and what Schwartz et al picked to study). Meanwhile, only 41% mentioned harms associated with interventions reported as beneficial (which, I admit, is lower than I would have guessed), and only 29% mentioned any study limitation (which is about what I would have guessed).

So now that we know that the medical reporting in the sample studied in this article was not so hot, what is the correlation between the press release and the news reporting:

For all 13 quality measures, newspaper stories were more likely to report the measure if the relevant information appeared in a press release (that is, a high quality press release) than if the information was missing (P=0.0002, sign test; fig 2⇓). This association was significant in separate comparisons for nine quality measures (fig 2). For example, when the press release did not quantify the main result with absolute risks, 9% of the 168 newspaper stories provided these numbers. By contrast, when the press release did provide absolute risks, 53% of the 77 newspaper stories provided these numbers (relative risk 6.0, 95% confidence interval 2.3 to 15.4). Because the accessibility of absolute risks varies with study design, we repeated this analysis for randomised trials only, in which absolute risks are always easily accessible. For the 140 newspaper stories reporting on randomised trials, the influence of press releases reporting absolute risks was the same as the main analysis (relative risk 5.8, 95% confidence interval 2.2 to 15.5).

It also turns out that the presence or absence of a quality measure in the press release had more influence than the presence or absence of the quality measure in the journal article abstract on whether that measure ended up being included in subsequently reported news stories:

Presence of a quality measure in the press release had a stronger influence on the quality of associated newspaper stories than its presence in the abstract (table 3⇓). The association between information in the press release and in the story was significant for seven of the 12 quality measures that could be compared (table 3). The corresponding association between information in the abstract and in the story was significant for two of the 12 measures. In absolute terms, the independent effect of information in the press release was larger than the effect of information in the abstract for eight of 12 measures. The only measure for which the absolute effect of the abstract was greater than that of the press release was for quantifying the main result (although press releases were substantially more influential for quantifying the main result with absolute risks).

Interestingly, the existence of a press release of high quality had little effect on reporting compared to reporting on articles that had had no press release issued at all for the basic study facts. High quality press releases did, however, positively influence reporting of quantification using absolute risks, mentioning harms, and discussing limitations of the study. More disturbingly, Schwartz et al suggests that poor quality press releases are worse than no press release at all in that important caveats and fundamental information were less likely to be reported in news stories if they weren’t included in the press release than if there was no press release at all. This, however, was a trend, because Schwartz et al point out that these latter findings were not statistically significant. The wag in me can’t resist asking why Schwartz et al even mentioned this last finding, even though it seems to make intuitive sense.

It’s not just medical journals, of course. Universities and academic medical centers have press offices, and these press offices frequently issue press releases touting the research of their investigators, sometimes in parallel with journals when a new article is published, sometimes independently, and, I can’t help but note, sometimes even before a researcher’s work has even passed muster in the peer review process. It turns out that Woloshin et al (including Dr. Schwartz) looked at this issue three years ago in a study published in the Annals of Internal Medicine entitled Press Releases by Academic Medical Centers: Not So Academic? They didn’t try to determine the influence of university press releases on subsequent media coverage (although I’d be shocked if such a study weren’t in the works as a followup to this one), but they did look at the quality of university press releases.

Because the investigators used similar methodology in their 2009 paper as they did in their 2012 paper, I’m not going to slog through this paper’s details as much as I did for the previous one. Its key findings are probably enough. Specifically, the results support the hypothesis that university press offices are prone to exaggeration, particularly with respect to animal studies and their relevance to human health and disease, although press releases about human studies exaggerated 18% of the time compared to 41% of the time for animal studies. Again, this seems to make intuitive sense, because in order to “sell” animal research results it is necessary to sell its relevance to human disease. Most lay people aren’t that interested in novel and fascinating biological findings in basic science that can’t be readily translated into humans; so it’s not surprising that university press offices might stretch a bit to draw relevance where there is little or none. In addition, a Woloshin et al observed a tendency for universities to hype preliminary research and to fail to provide necessary context:

Press releases issued by 20 academic medical centers frequently promoted preliminary research or inherently limited human studies without providing basic details or cautions needed to judge the meaning, relevance, or validity of the science. Our findings are consistent with those of other analyses of pharmaceutical industry (12) and medical journal (13) press releases, which also revealed a tendency to overstate the importance and downplay (or ignore) the limitations of research.

It’s well-known that industry press releases tend to do all of these things, which is the main reason I’m not harping on them so much in this post. It’s just expected that big pharma exaggerates because the evidence that it does is so overwhelming. In contrast, however, such exaggeration is usually not expected from universities. At least, it wasn’t in the past. Apparently today is a new day.

In human studies, the problem appears to be different. There’s another saying in medicine that statistical significance doesn’t necessarily mean that a finding will be clinically significant. In other words, we find small differences in treatment effect or associations between various biomarkers and various diseases that are statistically significant all the time. However, they are often too small to be clinically significant. Is, for example, an allele whose presence means a risk of a certain condition that is increased by 5% clinically significant? It might be if the risk in the population is less than 5%, but if the risk in the population is 50%, much less so. We ask this question all the time in oncology when considering whether or not a “positive” finding in a clinical trial of adjuvant chemotherapy is clinically relevant. For example, if chemotherapy increases the five year survival by 2% in a tumor that has a high likelihood of survival after surgery clinically relevant? Or is an elevated lab value that is associated with a 5% increase in the risk of a condition clinically relevant? Yes, it’s a bit of a value judgment, but small benefits that are statistically significant aren’t always clinically relevant.

Now here’s the kicker that suggests that investigators are part of the problem. Nearly all of the press releases included investigator quotes. This is not in itself surprising; investigator quotes would seem to be a prerequisite for even a halfway decent press release. What is surprising is that 26% of these investigator quotes were deemed to be overstating the importance of the research, a number that is strikingly similar to the percentage of press releases judged to be exaggerating the importance of the research (29%). Indeed, at one point Woloshin et al characterize the tone of many of these investigator quotes as “overly enthusiastic.” This suggests that it is the investigators, at least as much as their universities, who drive the exaggeration of the importance of their research findings. Our culpability as scientists in distorting our own science is even more glaring in light of the additional finding that all 20 major universities studied said that investigators routinely request press releases and are regularly involved in editing and approving them. In addition:

Only 2 centers routinely involve independent reviewers. On average, centers employed 5 press release writers (the highest-ranked centers had more writers than lower-ranked centers [mean, 6.6 vs. 3.7]). Three centers said that they trained writers in research methods and results presentation, but most expected writers to already have these skills and hone them on the job. All 20 centers said that media coverage is an important measure of their success, and most report the number of “media hits” garnered to the administration.

Five press release writers can churn out a heck of a lot of press releases in a year! Also, lack of outside evaluation can very easily lead to a hive mentality in which nothing is questioned.

There were several potential actions listed in the papers I’ve just discussed that universities and medical journals can take to lessen the problem, although it’s improbable that the problem of bad press releases will ever go away. Perhaps the most important (and most unlikely to be implemented) is for universities and medical journals to stop hyping preliminary research so heavily. It’s noted that 40% of meeting abstracts and 25% of abstracts that garner media attention are never subsequently published as full articles in the peer-reviewed literature. Unfortunately, universities are highly unlikely to show such restraint to any great degree, because the rewards of not showing restraint are too great. After all, it is the preliminary research that is often the most exciting to the public and—let’s face it—to scientists. It’s the sort of research that gets an institution (or journal) noticed. There’s a reason why journals like Nature, Cell, Science, and the NEJM like to publish preliminary, provocative studies. Unfortunately, it is just such research that is likely to be subsequently shown to be incorrect. Another thing universities could do is to to be sure to include as many of the quality indicators for each study as is appropriate, including absolute effects, study limitations, warnings that surrogate outcomes don’t always translate into clinical outcomes, and the like.

Perhaps most importantly, we scientists have to do two things. First, we have to avoid the temptation to oversell and overhype our results in press releases or when talking to the press. It’s a very strong temptation, as I’ve become aware, because we want to look good and we want to please our employers by making them look good too. We also want to justify the press release. Too many caveats and cautions make our work sound less important (or, more accurately, less certain) to a lay audience, and if it’s one thing that’s hard to explain to a lay audience it’s the inherent uncertainty in science. We can’t avoid that; we have to embrace it and work to explain it to the public.

Finally, I don’t want to leave you with the impression that reporters are off the hook. Nothing could be further from the truth. While some reporters definitely “get it” (Trine Tsouderos of the Chicago Tribune and Marilyn Marchione of the Associated Press come to mind), many do not. However, we as an academic community—investigators, universities, and medical journals—can greatly decrease the chances that reporters will produce grossly exaggerated or incorrect reporting if we make sure that their sources are scientifically accurate and don’t fall prey to the sins enumerated in the studies discussed here. That’s part of our job as scientists, every bit as much as making sure our science is rigorous and obtaining funding for our labs.