Since the COVID-19 pandemic arrived in 2020, my posts on or about New Years Day each year started to consist of my ruminations about various trends and tactics in science and medicine denial that I had noticed during the prior year. For instance, as the first year of the pandemic was shambling to a close, I noted how 2020 had been the year of so many physicians behaving badly in terms of promoting COVID-19 misinformation and outright quackery. Then, as the second year of the pandemic lumbered into the third, I pointed out how 2021 had become the year when the weaponization of the VAERS database to portray COVID-19 vaccines as deadly, something that antivaxxers had been doing for a long time prior to the pandemic to falsely portray childhood vaccines as a cause of autism and a number of other health complications they do not cause, had become mainstream, thanks to the pandemic. As 2022 faded into 2023, I then pointed out how in 2022 antivaxxers and other anti-public health activists had decided to claim that the public was being “gaslighted” about COVID-19. Of course, all of these trends were nothing new, because, as I repeat—at times ad nauseam—when it comes to quackery, science denial, and conspiracy theories, there is nothing new under the sun and everything old is new again. The pandemic just supercharged tactics that cranks, quacks, and antivaxxers had been using for years, if not decades, and, as newbies discovered them and started using them to build influencer audiences and/or promote a certain political orientation, migrated alarmingly to the mainstream.

As difficult as it is to believe now, March will usher in the fourth anniversary of the World Health Organization’s (WHO) declaration that the outbreak due to the novel coronavirus that had been given the name COVID-19 was officially a pandemic, meaning that we will soon be entering the pandemic’s fifth year. So what trend did I notice in 2023, the fourth year of the pandemic? The title of this post, of course, gives away the answer. Increasingly, a simplistic use of the evidence-based medicine (EBM) paradigm has been weaponized against not just pandemic-era public health nonpharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) like masks and social distancing to give a false impression that there is no evidence that any of these things work to slow the spread of COVID-19 or even just against COVID-19 vaccines. No, increasingly, misuse of the EBM paradigm to spread fear, uncertainty, and doubt has spread from the antivax crankosphere to seemingly “respectable” EBM mavens. Some of them (for instance—cough, cough—Vinay Prasad) have even started parroting a narrative “pioneered” by Aaron Siri, the lawyer for one of the granddaddies of the 21st century antivax movement, Robert F. Kennedy, Jr. (RFK Jr.), in particular his claim that existing childhood vaccines have not been properly tested in randomized double-blind saline placebo-controlled clinical trials. Worse, supposedly “respectable” physicians parroting this sort of message have been influencing medical students, one of whom seems to think that there is an elite RCT strike force out there able to do randomized clinical trials to answer every question about a fast-moving pandemic.

Of course, the reason presented for appealing to the EBM paradigm and RCTs (and, of course, meta-analyses of RCTs) as the highest form of clinical evidence in the EBM paradigm is presented as a value that everyone in science and medicine claims to prize: Raising the standard of evidence. After all, who could possibly argue with wanting more and higher quality evidence to support what we do in public health and medicine? Isn’t this entire blog dedicated to the very concept that the bar needs to be raised for the standard of evidence, that more science is needed? Absolutely! There’s just one problem (well, more than one actually). What I’ve increasingly been calling EBM fundamentalists argue is that raising the bar of evidence necessarily requires RCTs for practically everything, because the EBM paradigm tells them that RCTs are the highest, most rigorous form of clinical evidence. There is good reason to question that assumption at the heart of physicians casting doubt on public health interventions because there haven’t been RCTs that they view as adequately powered and rigorous testing the efficacy of these interventions and even better reason to question the —or even sometimes outright argument—that no intervention should be used until it has been validated in large RCTs, almost regardless of the practicality or ethics of doing such trials.

Long ago, as another pandemic (H1N1) bore down upon us, I learned a great term: Methodolatry. The term describes a phenomenon when the method matters more than the outcome and was sarcastically defined by a very senior epidemiologist and blogger who wrote under the pseudonym “revere” as “the profane worship of the randomized clinical trial as the only valid method of investigation.” For my part, I sometimes define EBM methodolatry by referencing an old Mike Myers sketch on Saturday Night Live about a Scotsman who frequently said, “If it’s not Scottish, it’s crap!” (There was always a huge emphasis on the word “crap.”) In doing impressions of these EBM methodolatrists, I would just substitute “an RCT” for “Scottish,” because it gives the general idea behind the misuse of the EBM paradigm, which promotes the idea that if it’s not an RCT it’s not evidence—or at least it’s not evidence not sufficiently rigorous to be even worthy of consideration in coming to a decision about how to deal with a medical or public health issue. Going back over revere’s old post, I noticed this comment about the article by Cochrane Collaboration scientist and physician Tom Jefferson—who is these days using similar tactics to cast doubt on masks and COVID-19 vaccines—casting doubt on the efficacy of the flu vaccine that had provoked revere’s ire:

My specific point is that we have here a concrete example of the misuse of EBM that is having real world effects, perhaps to the point that one or more people will die from novel H1N1 because this article convinced them the benefit of getting inoculated is so low it doesn’t outweigh the perceived risks.

Sound familiar? Let me just mention that the post that I am citing was published over 14 years ago. Indeed, you could take a number of articles citing the lack of RCTs about this NPI or for COVID-19 boosters or for a number of issues that have come up during the pandemic and change the words “novel H1N1” to “novel coronavirus” or “COVID-19,” and the point is just as valid today as it was in 2009. The only difference today is that far more EBM gurus seem to be promoting the same simplistic and misleading message that Tom Jefferson was back then; worse, the same idea is metastasizing from COVID-19 to the childhood vaccination schedule. Moreover, I would argue that this common pandemic-era misuse of the EBM paradigm is very much related to the “blind spot” for alternative medicine quackery that we’ve discussed here going back to the very beginning of this blog that allows quackery like homeopathy to be “integrated” into medicine in what used to be called complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) but is now more commonly called “integrative medicine” or “integrative health” and, more recently, the widespread promotion of ineffective drugs for COVID-19 like ivermectin and hydroxychloroquine that led me to liken ivermectin to acupuncture.

So let’s dive in deeper. First, of course, rather than just linking to prior posts or other sources, I will briefly recount what the EBM paradigm is, because you need to understand that before I can explain how some have twisted the EBM paradigm into methodolatry in order to spread the message that there is “no evidence”—yes, some of them use the term—that, for example, masks work.

The EBM paradigm

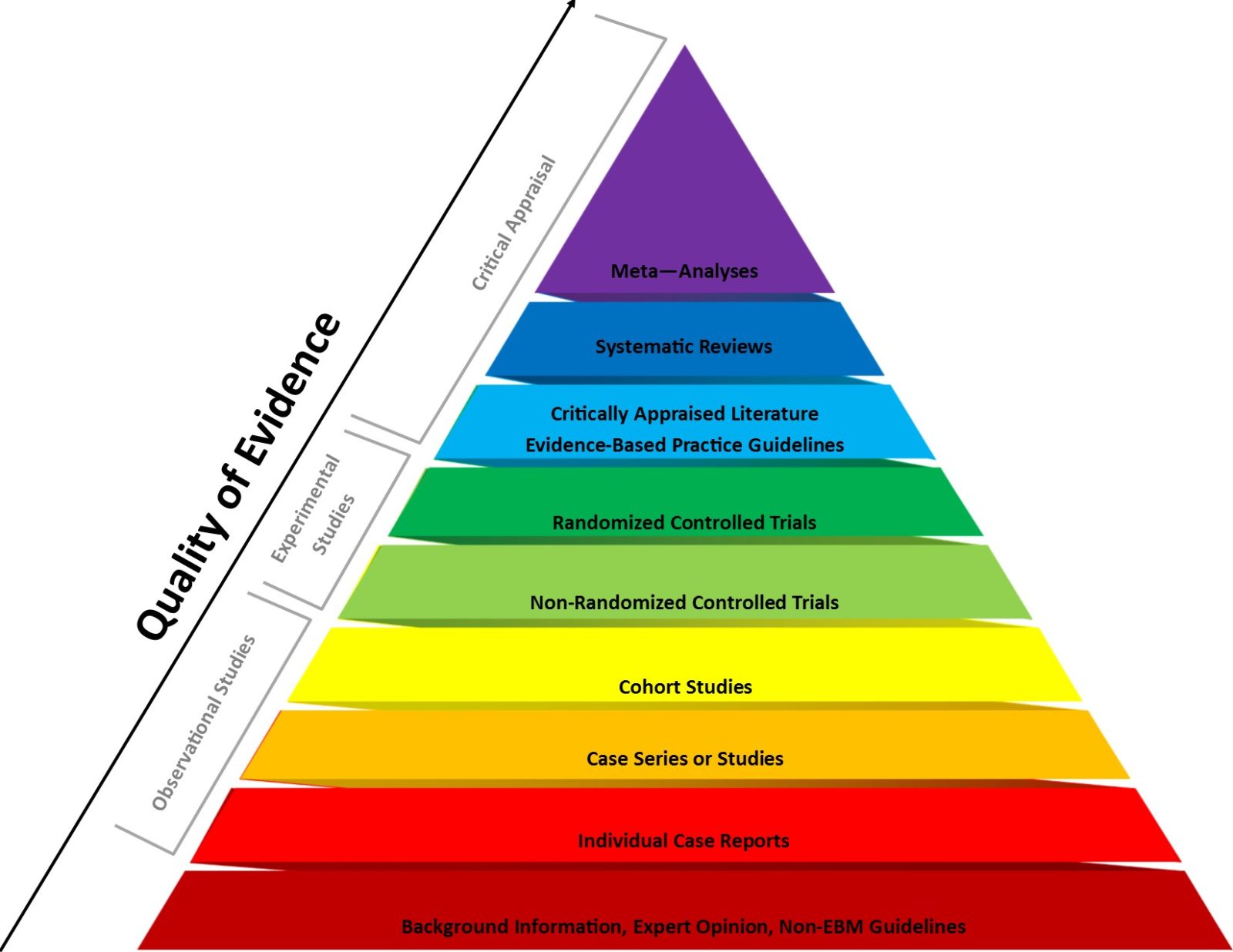

The EBM paradigm is often described in terms of the “evidence pyramid,” in which types of scientific evidence applied to medicine are ranked thusly:

The “classical” way of looking at levels of evidence from clinical studies not involving the synthesis of comes in the form of levels of evidence, as originally proposed by D. L. Sackett:

| Level | Type of evidence |

|---|---|

| I | Large RCTs with clear cut results |

| II | Small RCTs with unclear results |

| III | Cohort and case-control studies |

| IV | Historical cohort or case-control studies |

| V | Case series, studies with no controls |

Randomized controlled clinical trials are just that: clinical trials in which subjects are randomized to receive either the intervention or a control (such as a saline placebo) and then followed to determine which group has better outcomes, which are prespecified in the clinical trial protocol. The reason for randomization is to ensure that the two groups being compared resemble each other as closely as possible in characteristics relevant to the outcomes being tested. For example, if you’re testing a drug to treat hypertension, you would want the groups to be matched as closely as possible for, among other characteristics, age, race, sex, severity of hypertension, and relevant risk factors for poor outcomes. Ideally, these RCTs are then double-blinded, so that neither the subjects nor the doctors or medical personnel administering the drugs and assessing outcomes know which group any given subject is in. Double blinding is especially important in clinical trials with more subjective outcomes such as pain, for which placebo effects can be strong, but it’s also important even in trials with “hard” outcomes like tumor progression because it could affect how clinicians interpret tests and radiology studies if they know which group a given patient is in. Moreover, such clinical trials have strict inclusion and exclusion criteria, which ensure that those being treated actually have the disease, do not belong to a group that might be harmed by the drug, and are subjects who are likely to benefit if the drug does have efficacy; i.e., does work.

As you can see in the image above, in the EBM paradigm RCTs are ranked near the top of the pyramid for strength of evidence. Actually, as far as original clinical go, they are at the top. It is true that systematic reviews and meta-analyses of RCTs are ranked higher (i.e., as more rigorous), but remember that these are syntheses of existing RCTs, not original experimental clinical studies in which one intervention is tested against placebo or another intervention. Moreover, it is also true that, for certain questions, RCTs truly are the gold standard, as an RCT is the design that best minimizes bias, thanks to randomization and careful matching of the experimental versus the control group, plus blinding, which when done properly minimizes bias due to observation. None of us at SBM has ever denied that RCTs are indeed usually the most rigorous method for determining if a treatment works, and far be it from us to advocate for a lower standard of evidence. However, we have pointed out problems with the EBM paradigm.

Let me discuss one specific example. One problem with the EBM paradigm is that, because it values RCTs above all else, including huge quantities of epidemiological evidence, any evidence not from RCTs will automatically be relegated to a lower rung of certainty, no matter how copious the evidence is, how plausible from a basic science standpoint, or from how many disparate sources the evidence comes, all coming to the same conclusion. For example, let’s take a look at what the gurus of EBM at Cochrane have to say about the question of whether the MMR or MMRV vaccine causes autism. (Hint: Neither of them does.) Its review is Does the measles, mumps, rubella and varicella (MMRV) vaccine protect children, and does it cause harmful effects? Let’s see what it says.

While the review does conclude that there is “no evidence” that the MMR or MMRV combination vaccine causes encephalitis or autism, it does say:

Our certainty (confidence) in the evidence is slightly limited by the design of most of the studies. Nonetheless, we judged the certainty of the evidence for the effectiveness of the MMR vaccine to be moderate, and that for the varicella vaccine to be high. Our certainty in the evidence for autism and febrile seizures was also moderate.

Regular readers of SBM likely already know that in reality the evidence base of studies examining the question of whether vaccines cause autism is very large and has failed to find even hint of a whiff of an association between MMR (or MMRV) and autism. Yet, because the bulk of these studies consists of epidemiology, including one that encompassed 537,303 children representing 2,129,864 person-years of study, the certainty of the evidence behind Cochrane’s conclusion that MMR does not cause autism can never be more than “moderate” because by the very definition of the EBM paradigm and its ranking of sources of evidence, epidemiological studies always rank below RCTs. Note that it will never be possible to do an RCT to answer the question of whether vaccines like MMR increase the risk of autism because such a trial would be inherently unethical, as it would require randomizing a large number of children to the placebo control group, leaving them unprotected against a disease, a vaccine against which is considered standard-of-care for prevention of this disease; in other words, randomizing them to a group where we know that they would suffer harm. Moreover, such an RCT would require inordinately large numbers of subjects followed for such a long time as to be utterly impractical, as defenders of science-based vaccine requirements were explaining 15 years ago.

Another way to look at this is to examine the more recent version of the levels of evidence published by the Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine:

Levels of Evidence for Therapeutic Studies*

| Level | Type of evidence |

|---|---|

| 1A | Systematic review (with homogeneity) of RCTs |

| 1B | Individual RCT (with narrow confidence intervals) |

| 1C | All or none study |

| 2A | Systematic review (with homogeneity) of cohort studies |

| 2B | Individual Cohort study (including low quality RCT, e.g. <80% follow-up) |

| 2C | “Outcomes” research; Ecological studies |

| 3A | Systematic review (with homogeneity) of case-control studies |

| 3B | Individual Case-control study |

| 4 | Case series (and poor quality cohort and case-control study |

| 5 | Expert opinion without explicit critical appraisal or based on physiology bench research or “first principles” |

Under this paradigm, even systematic reviews of epidemiological studies are automatically at best level 2 evidence, at least when it comes to therapeutic studies. I do realize that there are other evidence rankings that put epidemiological evidence higher when it comes to questions of etiology or association. For example, it is noted here:

Since the introduction of levels of evidence, several other organizations and journals have adopted variation of the classification system. Diverse specialties are often asking different questions and it was recognized that the type and level of evidence needed to be modified accordingly. Research questions are divided into the categories: treatment, prognosis, diagnosis, and economic/decision analysis

Also:

In the absence of a current, well designed systematic review is not available, practitioners turn to the primary studies to answer their questions. The best research design depends on the question type. The table below lists optimal study methodologies for common types of clinical questions.

With a summary chart:

| Question Type | Optimal Study Methodology |

|

Treatment (Therapy) & Prevention |

|

| Diagnosis |

|

| Prognosis (Natural History) |

|

| Etiology or Harm (Causation) |

|

I note that EBM fundamentalists frequently ignore the precept that “if RCTs are impractical or unethical,” then cohort and case control studies must do. However, notice how, even the assessment of what is the optimal study design for each type of question only accepts non-RCTs for questions of etiology or harm (causation). In reality, questions of public health during the pandemic involve interventions, treatments, and/or preventatives, such as masking, social distancing, and vaccines.

The bottom line is that the EBM paradigm being applied to COVID-19 interventions was designed for a fairly narrow purpose: To rank the evidence primarily dealing with pharmaceutical drugs used for specific indications, in particular fairly simple, straightforward indications. Where the paradigm struggles is when it is applied to more complex, multifactorial conditions and questions. In particular, it struggles when applied to public health. Worse, it can be misused, and, unfortunately, a lot of EBM “gurus” seem predisposed to fall into the trap of doing so.

EBM misused a tool to attack public health interventions

Although I had been mulling the idea of how EBM had been weaponized against public health interventions and had started to write this article, I knew I had to complete it when I saw that Dr. Vinay Prasad had decided to finish 2023 with an article entitled Hospitals that reinstate universal masking with flimsy surgical masks are anti-science. And why is that? Because not “even one hospital is running a cluster randomized trial.” It’s a rather short rant (for Dr. Prasad) that concludes with:

Masking has made a fool of most scientists. They love bioplausible stories, but have failed to conduct even the most basic efficacy trials. Masking in hospitals is unlikely to slow the juggernaut of respiratory viruses— both iatrogenic and the more relevant q of across the community. Implanting the policy year over year— and running 0 cluster randomized trials— is embarrassing for medicine. We might as well open up a Vitamin C infusion center and pray to the sun god.

Actually, as I’ve argued before, insisting on RCTs for everything, regardless of whether RCTs are the most appropriate method to investigate a question or of how impractical or, in some cases unethical, an RCT might be has made a fool of fundamentalist EBM methodolatrists like Dr. Prasad and Dr. Tom Jefferson of Cochrane. While it is true that cloth masks are not great for this purpose, we do know from various reviews (and even reviews of systematic reviews) of what Dr. Prasad would consider “inferior” studies that N95 masks are effective in reducing transmission among healthcare workers and that masks in general can decrease transmission. It is not “antiscience” to say that, nor is it “antiscience” to question whether doing RCTs on masks of the type that Dr. Prasad is even ethical anymore given the current body of “lesser” evidence.

I will admit that Dr. Prasad’s little sarcastic dig at vitamin C infusions and praying to the sun god did lead me to chuckle, but not for the reason that Dr. Prasad no doubt intended. Remember before the pandemic, when Dr. Prasad was making fun of those of us who had spent so much time deconstructing quackery like homeopathy as having wasted our time and intellects fighting misinformation that, to him, was so obviously ridiculous that it was a waste of time compared to doing what he did? He even characterized it as “dunking on a 7′ hoop.” Yet, he clearly doesn’t understand that refuting the misinformation about, for instance, vitamin C infusions as a treatment for cancer is not at all straightforward.

If you want to get an idea of just how much EBM fundamentalism and methodology have polluted Dr. Prasad’s mind, remember that he was partially down with a favorite antivax trope that has been promoted by Robert F. Kennedy, Jr. and the lawyer for his antivaccine organization Children’s Health Defense, Aaron Sir, namely the claim that most of the vaccines in the CDC’s recommended childhood vaccine schedule had never been tested in an RCT versus saline placebo, the implication being that their safety and efficacy were in doubt. Indeed, let’s take a look at him falling for the “no saline placebo” RCT gambit:

Yet on hepatitis B vaccination, RFK Jr makes a fair point that we could target higher risk populations. At least that could be the central question of a randomized control trial. He’s also fair to ask if the particular timing of doses is optimized, or if it could be given it a later date. That could also be a randomized trial. I think this century will see the pediatric childhood immunization schedule the subject to a multi-arm, factorial RCT. It is better to launch that effort now before public distrust gets too out of control.

As I pointed out, this is a longstanding antivax trope to call for RCTs of the childhood vaccination schedule, despite the expense and the impracticality of such an effort. Dr. Prasad’s suggestion was nothing new, other than making the call into a “multi-arm, factorial RCT.” Indeed, at the time I challenged Dr. Prasad to design such a “multi-arm factorial RCT” of the childhood vaccination schedule that would be (1) feasible; (2) not require hundreds of thousands or millions of participants; and (3) ethical. Remember, any placebo-controlled RCT would require leaving one group unprotected against potentially deadly infectious diseases. I also pointed out how the antivax hatred of the birth dose of the hepatitis B vaccine is based more on moral outrage that leads them to rage that, because my baby or child isn’t at risk because my child doesn’t have premarital sex, share needles, or engage in what I consider morally dubious high risk behavior, my child shouldn’t need the birth dose of hepatitis B vaccines (or the vaccine at all). The subtext, of course, behind saying that the “high risk” groups should be targeted is that those “dirty vaccines” should be reserved for people who need them because they are dirty too, just as the call for only “high risk” people to be vaccinated against COVID-19 was based on the false believe that those who “lived right” and are “healthy” don’t need protection against the disease.

After having played footsie with RFK Jr.’s bonkers antivax conspiracy theories about the childhood vaccination schedule, Dr. Prasad didn’t take long to double down by writing The only real solution to vaccine skepticism: We need more randomized trials and a new phase IV safety system. Its blurb even led me to facepalm: “The way to address concerns about vaccines and other medical products is to hear what people are saying.” I discussed in detail how, in the name of winning back “trust,” Dr. Prasad doubled down on EBM fundamentalism and demanded RCTs of practically everything vaccine-related and how he was parroting old antivax tropes, but let’s just look at this one example here:

Trials of vaccine should contain at least 2 control arms. One a placebo arm of salt water, and another placebo arm perhaps containing adjuvant/ preservative/ or a different vaccine. Each control arm has different strengths and weaknesses. One allows accurate assessment of safety; the other preserves blinding, and or downstream behavioral change (think about it for a while).

Here we go again. Dr. Prasad is echoing yet another antivaccine talking point, namely the “no true saline placebo control RCTs” trope about vaccines. First of all, ethics, how does that work? As I discussed the other day, while it is appropriate to insist on a placebo-controlled RCT for a new vaccine against a disease for which there is currently no safe and effective vaccine licensed and available, it is completely unethical to do such a trial for a new vaccine against a disease for which there already exist safe and effective vaccines that are the standard of care. You cannot ethically randomize subjects to an arm where they receive less than standard, accepted medical care, such as randomizing a child to an arm where, for example, he doesn’t receive MMR because you want to test a new combination measles vaccine. The ethical thing to do is to test a new next generation vaccine against the existing standard-of-care previous generation vaccine for the same disease. This is methodolatry on top of methodolatry in that, not only is the RCT the only acceptable method of clinical investigation to Dr. Prasad, but it has to be a specific kind of RCT with a specific kind of placebo, clinical trial ethics and Helsinki declaration be damned!

But Dr. Prasad should know this. He’s an oncologist, and oncology trials were the type of RCTs that I used as an example to illustrate why placebo controls are often not ethical. Ethical RCT design is why most new chemotherapy agents used in oncology are either tested in an add-on design (standard of care + new drug versus standard-of-care + placebo) or a design that uses an active comparator (new drug vs. standard-of-care), so as not to require the randomization of subjects to an arm in which they receive no treatment for their cancer. Again, I’ve discussed this a number of times before. Again, saline placebo control is not the only appropriate placebo comparator. Adding it as a third arm in an RCT using a more appropriate comparator when that comparator has a long, well-established history of safety, with well-known and well-characterized potential adverse events, would do nothing but add expense and complexity to the clinical trial, as well as necessitate larger numbers of subjects in the phase 3 trials, all for no real benefit. Does Dr. Prasad honestly think that retesting existing vaccines in new RCTs in which there is a saline placebo control arm would reestablish “trust.” If he does, he doesn’t know the antivaccine movement, which would simply shift to another of its many talking points and/or find reasons to discount the new trials.

I could pick on Dr. Prasad for much longer, but unfortunately he’s not the only EBM fundamentalist up to such shenanigans. For example, Peter Götzsche has been abusing the interpretation of RCTs to portray COVID-19 vaccines as harmful, adding to his history of having invoked the “no saline placebo control” gambit before the pandemic to try to do the same about HPV vaccines. (Indeed, even before the pandemic Gøtzsche played footsie with antivaxxers so much that he only backed out of a speaking engagement for an antivax physicians’ group at the last minute because of embarrassment.) Indeed, such methodolatry seems to be a characteristic of EBM fundamentalists. Another example includes Tom Jefferson, who invoked similar gambits to claim that the entire childhood vaccination schedule is unscientific and unproven.

Worse, as Dr. Jonathan Howard has pointed out, there is now a whole cadre of physicians demanding RCTs for every COVID-19 intervention, regardless of whether such RCTs are practical or even ethical to carry out. Not coincidentally, he also noticed that the same physicians were often content to cite non-RCT evidence for purported harms of vaccines and COVID-19 interventions, a clear double standard. For example, Dr. Prasad might be well-known for demanding ever more rigorous data for various medical interventions, such as masking to slow the spread of COVID-19, but on the topic of myocarditis and COVID-19 vaccines, he’s long seemed quite happy with a low-quality study that misused the VAERS database. He also seemed quite happy doing a commentary about “obsessive criticism” of him and his buddy Prof. Ioannidis social media based on even lower quality analyses. Worse, this misuse of EBM seems to be influencing trainees, such as medical students.

Indeed, calling for a bunch of RCTs that can’t be done is the point, as the goal is not, as claimed, to advocate for a higher standard of evidence but rather to cite the existence of impossible studies not meant to be taken seriously as a tactic to cast doubt on the evidence base for interventions against COVID-19 that they don’t like, such as masks and vaccine mandates. If you doubt me, just consider how Dr. Prasad has embraced the antivax message of “do not comply” to any intervention (especially vaccines) that he considers to have insufficient evidence, meaning (by EBM definition) insufficient or no RCT evidence. I once asked whether EBM fundamentalism contributed to COVID-19 contrarianism. I’m forced to conclude reluctantly that the answer is yes.

What do I mean by fundamentalism? This concluding paragraph of a rant by Dr. Prasad about how nobody seems to follow EBM anymore sounds almost religious in its fervor:

Evidence based medicine is delicate, vulnerable, but also profoundly beautiful and rational. It alone is the logical way to implement and pursue costly, invasive, intrusive, and disputed medical and public health interventions. As such, it is a forced move in human development. Even if it withers and dies in the next few years— and it is well on its way to demise— it will be reborn and rekindled in a future moment. It the telos of progress in science. If only the stars could see that.

I mean, seriously? EBM dying and rising again? Get a grip on yourself. EBM is just a tool, a framework to evaluate evidence, and like any other tool or framework it has strengths and weaknesses. In its current form, EBM’s key strength, where it performs the best, is in the evaluation of pharmaceutical drug treatments for well-characterized medical conditions and diseases, in particular as a tool to determine if a new drug is sufficiently effective and safe to be licensed by regulatory agencies for sale. No one, least of all I, would propose replacing EBM with something else for this purpose. However, when it comes to whole swaths of medicine, particularly the “integration” of alternative medicine into medicine as CAM or “integrative medicine,” it has serious deficiencies. That was the whole reason that Steve Novella and colleagues proposed SBM instead and started this blog 16 years ago. It is the reason why I pointed out how SBM could have prevented one waste of resources with respect to ivermectin as a treatment for COVID-19 when EBM demanded more and more RCTs before it would conclude that ivermectin doesn’t work. Now it’s being used to undermine confidence in what has long been considered as close to settled science as there can be, childhood vaccines.

The problem is that, like all fundamentalism, EBM fundamentalism refuses to acknowledge the serious shortcomings of its god that need to be addressed and fixed. Sure, methodolatrists like Dr. Prasad will concede some relatively minor shortcomings, but for him these shortcomings can only be fixed by the ever more zealous application of EBM principles—but only when it comes to addressing questions whose answers thus far he doesn’t like. How is that any different from the ideology that EBM fundamentalists accuse critics of? Remember, an accusation like that is very often a confession. Again, EBM is a tool, and it is not “antiscience” to point out where it falls short or suggest ways in which it might be improved.