Ngram is a Google analytic tool/way to waste lots of time on the internet, a byproduct of Google’s scanning millions of books into its database. In a matter of seconds, Ngram scans words from about 7.5 million books, an estimated 6 percent of all books ever published. Type a word or phrase in the Ngram Viewer search box and in seconds a chart of its yearly frequency will appear. You can also search for a series of words or phrases and the Viewer will provide a color-coded chart comparing frequency of use. More sophisticated searches (e.g., making the search case sensitive, or not) are also possible.

As explained in the New York Times, researchers “have used this system to analyze centuries of word use, examining the spread of scientific concepts, technological innovations, political repression, and even celebrity fame.” Erez Aiden, a computer scientist who helped create the word frequency tool, says he and his co-researcher, Jean-Baptiste Michel, wanted “to create a scientific measuring instrument, something like a telescope, but instead of pointing it at a star, you point it at human culture.” In fact, the title of their new book is Uncharted: Big Data as a Lens on Human Culture. Still, they caution that, like other scientific tools, Ngram’s results can be misinterpreted. An example: the fax machine. If you query that term, it looks as if the fax appears almost instantaneously in the 1980s. In reality, the machine was invented in the 1840s but was then called the “telefax.”

If Ngram can search for scientific concepts, how about unscientific concepts? What might a search of unscientific concepts tell us about our human culture? Let’s find out.

Searching for alternative medicine

Let’s start with the search “alternative medicine, complementary medicine, complementary and alternative medicine, integrative medicine,” with no case sensitivity. But first, some technicalities applicable to all of the Ngram searches in this post. I searched only English-language books and applied a smoothing factor of 3. (Smoothing and other features are explained here.) I chose 3 for the sole reason that 3 is used by Google in its sample Ngram search for “Albert Einstein, Sherlock Holmes, Frankenstein.” (Not sure what conclusion, if any, about human culture is suggested by that search.)

In searching, I wasn’t particularly interested in the absolute frequency with which a word or phrase appeared (as represented on the y axis), but rather how it compared in frequency to other words and phrases, what year each appeared (as represented on the x axis) and its trajectory over time. The database only goes through 2008, so searches have to end there. Also, the searches have to assume that the word or phrase has only one definition, or perhaps one definition that dominates all others. We also have to remember that only books were scanned, not, for example, academic journals or popular magazines. Or blog posts, for that matter. For those of you used to scientific precision and charts offering meticulous measurements, you’ll have to forgive my rough calculations and interpretations. Finally, sorry for the fuzziness of these charts. (If you’d like a clearer picture you can follow along on your computer by performing the same Ngram search.)

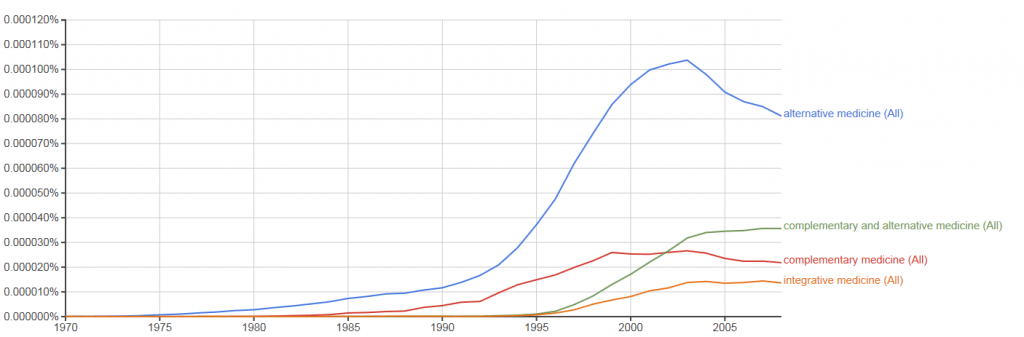

You’ll see that alternative medicine is far more prevalent than the others. It’s barely on the radar in 1970, climbs gradually to 1990, and then shoots off beginning in around 1993, peaking in about 2003 and then declining. Complementary medicine starts to show up in 1980, with a more gradual ascent, peaking earlier, around 1999, then flattening and declining. Complementary and alternative medicine doesn’t take off until full 15 years later, in 1995, peaking in 2004 and flattening, then declining a bit. Integrative medicine appears at about the same time and follows roughly the same trajectory as, but with less frequency than, complementary and alternative medicine. What was going on that might explain, at least in part, these trajectories?

There are some interesting parallels. The predecessor to NCCAM, the Office of Alternative Medicine (OAM), was funded with taxpayer money in 1991, established in 1992, and made part of the National Institutes of Health in 1993, all around the time the term alternative medicine started its steep ascent. The first national survey of alternative medicine use, then referred to as “unconventional medicine,” was published in 1993 as well. The article discussing the survey contained the misleading, but often quoted, claim that one-third of adult Americans used at least one unconventional therapy, a percentage puffed up by rebranding conventional treatments as unconventional.

The OAM became the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine in 1998, about three years after the phrase “complementary and alternative medicine” began its appearance. The first Consortium on Integrative Medicine met in 1999, and the Consortium of Academic Health Centers for Integrative Medicine was formed in 2000. “Trends in Alternative Medicine Use in the United States, 1990-1997,” was published in JAMA in 1998. It used the same questionable methodolgy to reach a conclusion that alternative medicine was increasingly popular. This was followed, in 2002, by “Complementary and Alternative Medicine Use Among Adults: United States, 2002.” Once again, conventional modalities such as diet (including a vegetarian diet) and exercise were counted as CAM. (Note the ever-changing nomenclature, perhaps an indication of confusion over just what it is we are measuring.)

As has been pointed out before, the creation of NCCAM (and its predecessor, the OAM) and the first two articles about CAM use, were the products of Wayne Jonas, David Eisenberg, Tom Harkin and others who want to promote widespread adoption of CAM into American healthcare, evidence be damned. This brings us to a “chicken and egg” question. Which came first? The increasing cultural significance of CAM, as evidenced by Ngram, or its ardent promotion by aficionados? Was increasing cultural significance the result of this PR campaign? (We know, of course, it’s not the evidence of safety or effectiveness that encourages CAM use.)

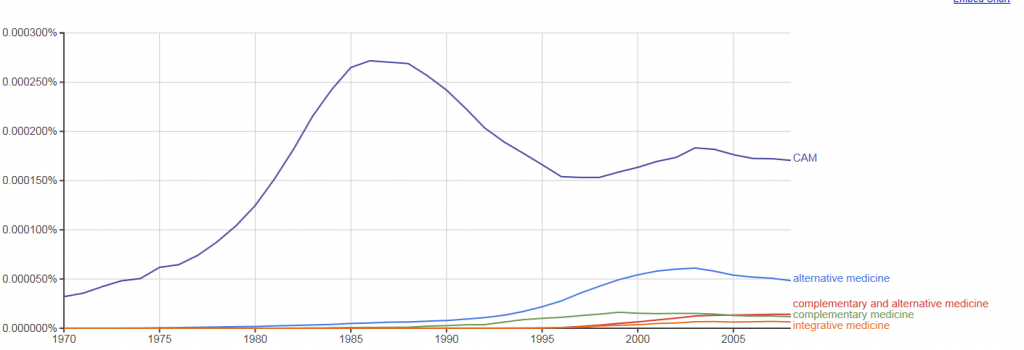

But what about the term “CAM” itself? Here we run into some search issues. In addition to being an acronym for complementary and alternative medicine, it can stand for computer-aided manufacturing, the Construction Association of Michigan, and the Contemporary Art Museum in Raleigh, NC. It is also the NYSE symbol for a company, a person’s name and a machine part. And our search is complicated by the fact that we have to drop the case-insensitivity filter as that would likely pick up more irrelevant uses. Still, here’s what the search looks like, for what it’s worth.

You’ll see that the word “CAM” is already around in 1970, peaks in about 1987, falls and then rises again a bit, only to level off at about the same time as the other terms. Yet it falls as the others are taking off. It is also far more common than the others, although we don’t know how much any of this can be attributed to its different meanings.

CAM practitioners and practices

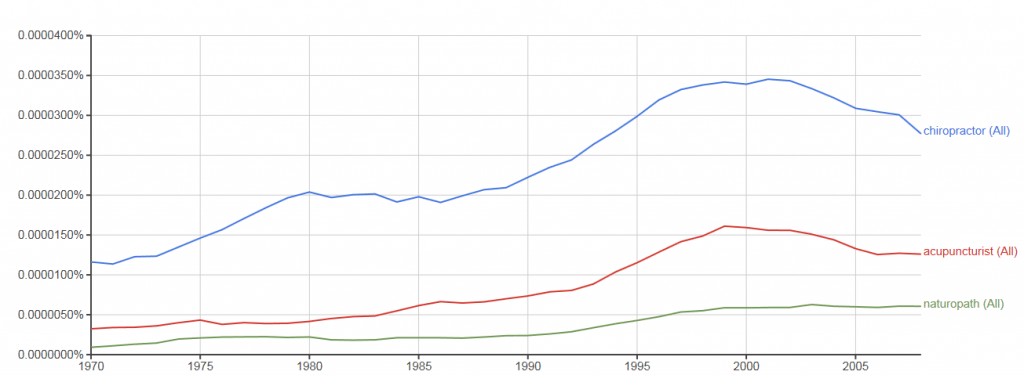

Let’s move on to specific CAM practitioners. First, we compare chiropractor, naturopath and acupuncturist. Since Traditional Chinese Medicine and Oriental Medicine can be both modifiers describing a type of practitioner and nouns designating the practice itself, I excluded them, although we will get to them in the next chart. (Note that we are on an entirely different frequency scale here.)

As would be expected, chiropractor comes in first, followed by acupuncturist, then naturopath. I was surprised that acupuncturist was not used more frequently but perhaps this can be explained by the fact that acupuncturists go by more names than the other two: Traditional Chinese Medicine practitioner, Oriental Medicine practitioner, Doctor of Oriental Medicine, and so forth. What is more intriguing is that chiropractor and acupuncturist both hit a peak about 2000 and then decline. Recall that this was true of some terms on the first chart.

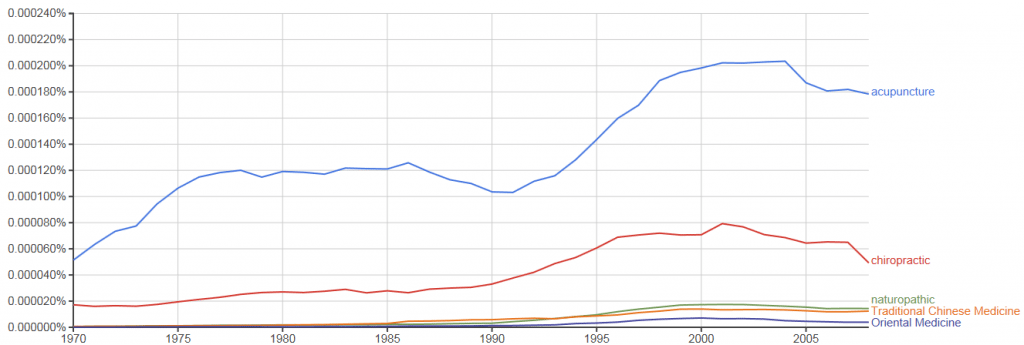

Next, we switch to the practices themselves (again, note the change in frequency scale.) Here’s how chiropractic, acupuncture, naturopathic, Traditional Chinese Medicine, and Oriental Medicine compare.

Note how acupuncture is far ahead of the other terms. Naturopathic, Traditional Chinese Medicine and Oriental Medicine hardly appear before 1990, rise a bit, and then flatten. And notice the upticks starting around 1990, again like the first chart. As with the practitioners, the words “acupuncture” and “chiropractic” have seen a decline in frequency from their peaks.

Homeopathy rules?

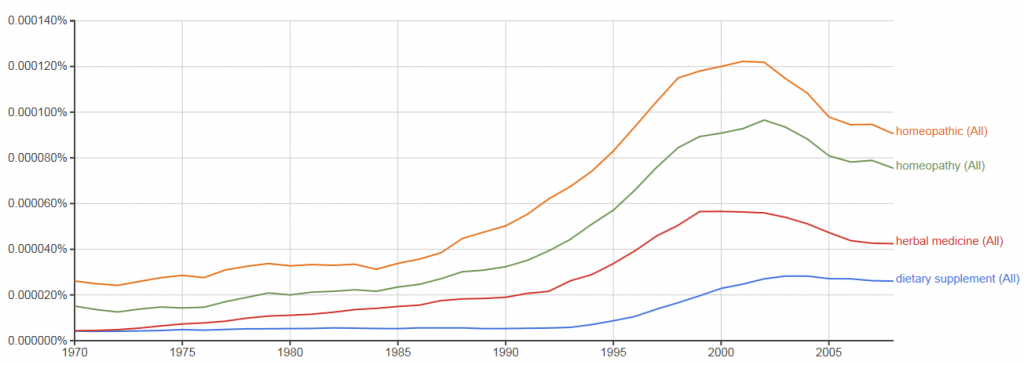

I’ve saved the most surprising for last. Here we compare homeopathic (because the products are often called homeopathic remedies), homeopathy, herbal medicine, and dietary supplement.

I was surprised to see how far homeopathic/homeopathy surpassed dietary supplement, even though far more of the latter is sold each year. Some of this might be explained by the use of “homeopathic” to describe a practitioner as well, although they are generally called homeopaths. Even herbal medicine is more frequent than dietary supplement. Interestingly, all four share a similar trajectory, with the first three falling since 2000-2005, and dietary supplement remaining flat since around 2003. Note that dietary supplement begins to climb around 1994, the same year dietary supplements were deregulated by the Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act (DSHEA).

Conclusion (if there is any)

What have we learned? Well, nothing maybe, but Ngram is an interesting analytic tool. It would take someone with far more expertise than me to cipher this data but here are two tentative conclusions. First, vigorous advocacy by CAM proponents over a short period of time was followed by an increased use of some CAM terms, indicating an increased cultural awareness of CAM. A popular rationale for research funding, inclusion in medical curricula, selective use in integrative medicine, licensing of practitioners and the like is a supposed public demand for CAM. But was demand, at least in part, ginned up by the increased cultural awareness following these advocacy efforts? Did more people try CAM not because of a perceived benefit, but because it was on the cultural radar? Is demand leading or is it following? Second, the frequency of CAM-related terms is decreasing. Perhaps this is temporary, or is an illusion created by the short time span covering the decrease. We can only hope this means a real decrease in the cultural impact of CAM, despite its advocates’ best efforts. Time will tell.