For $8,000 a liter, $12,000 for two, a company called Ambrosia Health will pump you full of plasma from young (typically, 16-25 years of age) donors, a treatment aimed at . . . well, they can’t tell you that because it might get them into trouble with the FDA. However, according to the company’s website, Ambrosia Health “is interested in” parabiosis, which (hint, hint) “has been shown in mice to reverse aging”.

So interested, in fact, that Ambrosia’s founder, Jesse Karmazin, was willing to extrapolate all sorts of health benefits from the results of experiments on mice and conduct a clinical trial of young blood plasma infusions on human subjects, who paid thousands of dollars each for their treatments. Despite Karmazin’s repeated promises, and his glowing reports of benefits, the trial results have never been published, or made public in any form for that matter. All of this has earned Karmazin rebukes from the scientific community and the FDA’s notice, but has not stopped Ambrosia from currently offering “young blood” (as they are often called, although it’s actually blood plasma) infusions at two U.S. locations.

According to an excellent news report published in HuffPost late last year, Karmazin, a 2014 Stanford med school graduate, left his Brigham & Women’s Hospital residency program in 2016 to pursue his interest in aging as a “treatable condition.” (He does not have a license to practice medicine in any state.) He got the idea for infusions of plasma from young blood donors from mouse studies showing improvements in older mice’s health when they were surgically joined to younger mice, thereby mixing the older and younger mice’s blood.

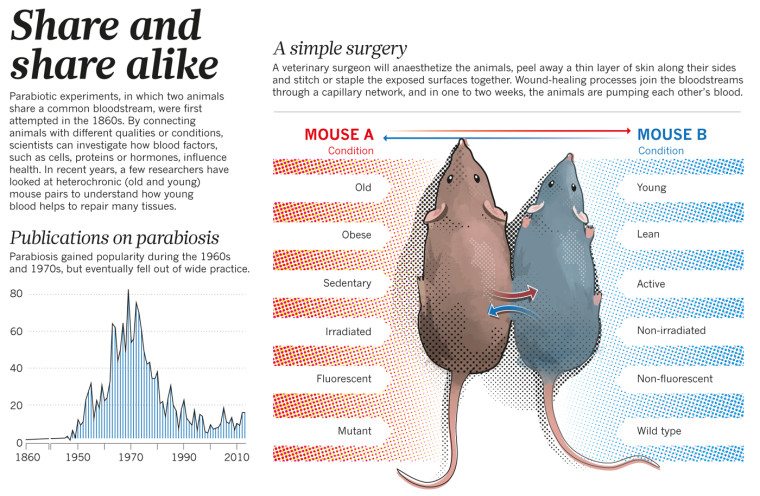

As SBM’s Dr. Steve Novella explained, the technique of surgically joining mice so that they share the same circulatory system, called parabiosis, was used in physiology studies to determine if blood factors affected some physiological property (e.g., the effects of hormones). In the 1950s, researchers discovered that biomarkers of youth returned in old mice connected to young mice and the old mice lived longer and experienced rejuvenating effects. (The younger mice didn’t fare so well; they had shorter life spans.) What we don’t know is why this happened:

does this benefit come from specific factors in the blood or from the fact that they are sharing their entire circulatory system? In other words, are the younger mouse’s kidneys, livers, and lungs just supporting the older mouse’s organs by doing the heavy lifting of cleaning and oxygenating the blood? This is probably a factor, but the other option is that there are proteins in the young mouse blood that exist in smaller amounts in the older blood.

In any event, by the 1970s, parabiosis experiments had run their course because researchers had learned what they could and more stringent regulation of animal experiments made the research more difficult.

The significance of findings from parabiosis experiments has been called into question by scientists, according to the HuffPost report, including Irina Conboy, who researches aging and rejuvenation at Berkeley:

Maybe there are secret sources [for human rejuvenation] in young blood . . . But there is no scientific evidence for that.

The indecisive results of mouse studies and total lack of evidence of benefit in humans apparently didn’t dissuade Karmazin, who, in 2016, announced a clinical trial of young blood infusions, for which participants age 35 and older would pay $8,000 for about 2 liters of young plasma infused over one to two days. Institutional Review Board oversight was provided through The Institute for Regenerative and Cellular Medicine, whose official defended the trial on the ground that, although controversial, she told HuffPost “there’s a lot worse being done”.

The trial was clouded by questionable ethics and criticisms from experts. One of the physicians involved in the study had been charged by the Medical Board of California with unprofessional conduct, including an allegation that he diagnosed a patient with “chronic Lyme” and treated the patient with daily antibiotic infusions, leading to significant side effects. Per an agreement with the Board, the physician was reprimanded but did not admit wrongdoing and was allowed to continue practicing.

Another issue was sourcing some 80 gallons of young blood plasma from blood banks that, as the HuffPost points out, usually don’t separate blood out by donor age and sell it to rejuvenate older people. Rather, “their primary mission is to provide donated blood for hospital patients and save lives”. Eventually, Karmazin found two blood banks to supply his trial, although one no longer does business with him after the HuffPost revealed some unpleasant facts about a blood drive specifically directed at millennials, who were called upon (with incentives like movie and amusement park passes) to “step up and donate” to save lives. The blood bank wouldn’t tell reporters whether young blood plasma from its “Generation Give” drive was sold to Karmazin and denied any connection between the reporters’ inquiry and its decision to terminate the relationship with Ambrosia.

The trial’s informed consent process was questioned as well:

Ambrosia told trial participants that “abundant data” from mice studies suggested young plasma infusions could help with “rejuvenation,” but the company said it couldn’t guarantee participants any specific results, such as the treatment of a disease. Rather, it noted in its informed consent form that there are “no known improvements” directly related to young plasma infusions. In fact, the form contained “an appalling lack of detailed explanation of what the actual effects of this intervention are supposed to be,” said Alta Charo, a professor of law and bioethics at the University of Wisconsin-Madison who reviewed Ambrosia’s form at HuffPost’s request.

The lack of benefit versus the risk, which can include hives, lung injury and deadly infections, also worried scientists. The director of transfusion medicine at Michigan, Robertson Davenport, told reporters that a transfusion for anti-aging purposes is “not scientifically or medically justified and exposes patients to risk of harm”. Dobri Kiprov, chief of the immunotherapy division at California Pacific Medical Center, told MIT Technology Review that he tries to dissuade patients from young blood transfusions: “To expose people to danger unnecessarily – in my mind, that is really horrible”.

Finally, the significance of the trial’s object – to measure the effect of young blood plasma on about 100 biomarkers – was called into question. According to Irina Conboy, the biomarker results will be meaningless because there is no control arm and, in any event, blood biomarkers change for many reasons: “If you eat a meal, leptin changes”. Another expert noted that changes in biomarkers aren’t necessarily indicative of a change in actual health status.

Ambrosia’s clinical trial ended in January 2018. Despite the lack of published results, Karmazin and an Ambrosia official who has since left the company touted the trial as “a great success,” claiming to various media outlets that an Alzheimer’s patient showed improvements after one treatment, grey hair turned darker for a person in their 60’s, there was a 10% reduction in patients’ blood cholesterol levels and a 20% fall in the level of amyloids, erections resumed in a patient with depleted testosterone levels, “really dramatic improvements to biomarkers for inflammation,” as well as improvements in a tremor for a Parkinson’s patient, arthritis symptoms, sleep, memory, focus, appearance, muscle tone, and energy levels. A patient with chronic fatigue syndrome “feels healthy for the first time” and “looks younger”.

In other words, just the type of placebo effects you’d expect from patients with variable symptoms who received an expensive, elaborate, time-consuming treatment based on pre-existing expectations of benefit, plus a few random improvements in biomarkers that cannot be reliably attributed to the treatment and may be clinically meaningless.

The FDA takes note

Ambrosia operated five U.S. clinics at one time but ceased treatments following a sternly-worded advisory from the FDA and statement from the FDA Commissioner “cautioning consumers against receiving young donor plasma infusions that are promoted as unproven treatment for varying conditions”, both issued in February of this year. The agency, which regulates blood products, made clear that it was watching and not liking what it was seeing.

Without naming Ambrosia or any other company, then-Commissioner Gottlieb condemned “unscrupulous” and “bad actors” who were charging thousands of dollars and preying upon patients, touting young plasma as a remedy for conditions as diverse as “normal aging and memory loss to serious diseases like dementia, Parkinson’s disease, multiple sclerosis, Alzheimer’s disease, heart disease or post-traumatic stress disorder”, uses for which plasma is not FDA-recognized or approved.

Our concerns regarding treatments using plasma from young donors are heightened by the fact that there is no compelling clinical evidence on its efficacy, nor is there information on appropriate dosing for treatment of the conditions for which these products are being advertised. . . . Moreover, reports we’re seeing indicate that the dosing of these infusions can involve administration of large volumes of plasma that can be associated with significant risks including infectious, allergic, respiratory and cardiovascular risks, among others.

Commissioner Gottlieb said the FDA would consider taking regulatory and enforcement actions against companies who risk patients’ health with “uncontrolled manufacturing conditions” or by “promoting so-called ‘treatments’ that haven’t been proven safe for effective for any use”. The FDA urged patients and physicians to report adverse events from young blood treatments to the agency.

The effect of the FDA’s threat on Karmazin wore off fairly quickly. Ambrosia recently reentered the young blood biz with locations in Tampa and San Francisco and a bare-bones website only hinting at the putative age-defying effects of its product. And:

Plasma is an off-label treatment, so we cannot make any claims about its effectiveness. There may be risks to this treatment and your doctor will advise you on these risks.

“Your doctor?” That term gives me pause. If a physician’s only encounter with a patient consists of signing off on a blood transfusion, is he really “your doctor,” especially where there is, presumably, no referral from the physician who is actually following the patient for the particular condition he or she seeks to remedy with the transfusion? Can you call a physician who operates wholly outside the patient’s care team “your doctor”? While it is true that a physician-patient relationship is established, such that the patient could sue the physician for malpractice, calling the physician “your doctor” implies a familiar relationship with the patient that is belied by the facts. I would argue that “a physician” is a more suitable reference to this person hired by the company to oversee what may be a single encounter.

Considering the negative information that comes up in a Google search of “young blood” infusions in general and Ambrosia Health in particular, it’s hard to imagine anyone shelling out thousands of dollars for these unproven and potentially risky treatments. Unfortunately, as we’ve seen time and again here at SBM, good science doesn’t stop people from making bad health decisions about vaccination, autism treatments, CAM for cancer and other serious diseases, stem cell treatments, homeopathy, naturopathy, chiropractic, integrative medicine, functional medicine, dietary supplements, or acupuncture. Sadly, it’s unlikely “young blood” infusions will be any different.