A couple of weeks ago, in a review of the Mayo Clinic Book of Home Remedies, Harriet Hall expressed relief that she hadn’t found any “questionable recommendations for complementary & alternative medicine (CAM) treatments” in that book:

Since “quackademic” medicine is infiltrating our best institutions and organizations, I wasn’t sure I could trust even the prestigious Mayo Clinic.

The Home Remedies book may be free of woo, but Dr. Hall was right to wonder if she could trust the Mayo Clinic. About a year ago I was asked to comment on an article in the American Journal of Hematology (AJH), in which investigators from the Mayo Clinic reported that among a cohort of lymphoma patients who were “CAM” users,

There was a general lack of knowledge about forms of CAM, and about potential risks associated with specific types of CAM…

This suggests the need to improve access to evidence-based information regarding CAM to all patients with lymphoma.

No surprise, that, but I couldn’t help calling attention to the paradox of one hand of the Mayo Clinic having issued that report even as the other was contributing to such ignorance:

The Mayo Clinic Book of Alternative Medicine details dozens of natural therapies that have worked safely for many patients in treating 20 top health issues. You may be surprised that Mayo Clinic now urges you and your doctor to consider yoga, garlic, acupuncture, dietary supplements and other natural therapies. Yet the record is clear. Many of these alternative therapies can help you achieve reduced arthritis pain, healthier coronary arteries, improved diabetes management, better memory function and more.

Nor could such a paradox be explained by the right hand not having known what the left was doing: Brent Bauer, MD, the Director of the Mayo Clinic Complementary and Integrative Medicine Program, is both the medical editor of the Book of Alternative Medicine (MCBAM) and a co-author of the article in the AJH.

As chance would have it, I had picked up a copy of the latest (2011) edition of the MCBAM only a couple of days before Dr. Hall’s post. Does it live up to its promises? Do its “straight answers from the world’s leading medical experts” respond to “the need to improve access to evidence-based information regarding CAM?” Let’s find out. In some cases I’ll state the implied questions and provide the straight answers.

The Introduction

In the Introduction, Dr. Bauer asserts that “an opportunity has risen that may hold the promise of a new paradigm for better health.” He makes several, implicit or explicit assertions that are repeated throughout the book:

The best way to manage an illness is to prevent it from happening in the first place…It’s in this environment—one in which Americans are seeking greater control of their health—that we’ve seen explosive growth in the field of alternative medicine. People are looking for more “natural” or “holistic” ways to maintain good health…

The implied question: Should people be looking for such things? Is there anything useful in “alternative” (or “natural” or “holistic” or “integrative”) medicine, different from what modern medicine and public health have learned by rational inquiry, for preventing an illness?

The straight answer: No.

Dr. Bauer goes on:

By combining the best of complementary and conventional health care practices to meet your individual needs, you’ll be practicing integrative medicine.

The implied question: Do the world’s leading medical experts know which are the “best complementary” practices, or even if any of them work?

The straight answer: No. Most “alternative” or “complementary” practices are known not to work or are vanishingly unlikely to work. Exceptions are a few botanical medicines, but these are overhyped and are disadvantageous compared to purified, precisely dosed, well-studied pharmaceuticals. Other claimed exceptions, such as rational diets, exercise, manual techniques for musculoskeletal complaints, and relaxation techniques, are not “alternative” at all.

Dr. Bauer again:

…an increasing number of treatments once considered “on the fringe” are slowly being incorporated into conventional medicine.

The implied question: If this is true, is it because those treatments have been shown to be effective?

The straight answer: No. Over the past several years, an increasing number of treatments once considered promising by naïve “alternative medicine” proponents have been tested in clinical trials and shown to be ineffective. R. Barker Bausell, the former Director of Research at the University of Maryland Complementary Medicine Program, reviewed this literature for his 2007 book, Snake Oil Science; the Truth About Complementary and Alternative Medicine:

Because of its emphasis upon high-quality scientific evidence, this book could not have been written in April 1999…Now, however, enough evidence has accumulated to permit the first scientific evaluation of complementary and alternative medicine. [p. xv]

And what did Bausell’s evaluation reveal?

There is no compelling, credible scientific evidence to suggest that any CAM therapy benefits any medical condition or reduces any symptom (pain or otherwise) better than a placebo. [p. 254]

Edzard Ernst, the most prolific “CAM” researcher of the past 20 years, offered similar conclusions in his 2008 book, co-authored with Simon Singh, Trick or Treatment: the Undeniable Facts about Alternative Medicine:

The bottom line is that none of the above treatments (herbal medicine, chiropractic, acupuncture, homeopathy) is backed by the kind of evidence that would be considered impressive by the current standards of medical research. Those benefits that might exist are simply too small, too inconsistent and too contentious. Moreover, none of these alternative treatments (apart from a few herbal medicines) compare well against the conventional options for the same conditions. This dismal pattern is repeated [for] many more alternative therapies. [pp. 238-9]

Back to the Mayo Clinic’s Bauer:

…what’s considered alternative today may be conventional tomorrow. In addition, using a particular therapy to treat one condition may be an accepted medical practice, but using it to treat another condition may not. A case in point is chiropractic care. There are numerous studies to back up the effectiveness of chiropractic therapy for low back pain. However, use of chiropractic techniques to treat high blood pressure would still be considered an alternative practice by many because there’s not sufficient evidence that it’s effective.

The implied question: Does this mean that there is likely to be sufficient evidence in the future? In other words, is there any anatomic or physiologic basis for predicting that chiropractic “care” might treat high blood pressure?

The straight answer: No. The idea is so implausible (and dangerous, in the case of neck manipulation) that it would be unethical to perform trials.

In the introduction, Bauer also makes these promises:

The purpose of Mayo Clinic Guide to Alternative Medicine 2011 isn’t only to inform you about various products and practices, but to guide you as to which appear to be of benefit and may help treat or prevent disease and which are of no benefit and could even be dangerous.

Let’s see whether those promises are fulfilled as we move on to a few specific treatments.

“Our Top 10”

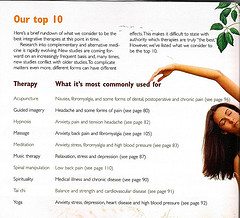

Sorry that the picture below didn’t come out sharply enough, but here are the two paragraphs at its top—a weasel wordfest similar to the book as a whole:

Here’s a brief rundown of what we consider to be the best integrative therapies at this point in time.

Research into complementary and alternative medicine is rapidly evolving. New studies are coming forward on an increasingly frequent basis and, many times, new studies conflict with older studies. To complicate matters even more, different forms can have different effects. This makes it difficult to state with authority which therapies are truly “the best.” However, we’ve listed what we consider to be the top 10.

Notice that the list is in alphabetical order, so we’re not told which of these ‘therapies’ the Mayo Clinic really likes. Notice, also, that the column on the right has to do with popularity, not validity. Most of the Top 10 are not “CAM” at all, as long as they’re used for rational purposes: guided imagery, hypnosis, meditation, music therapy, spirituality and yoga for “stress” or pain, spinal manipulation for low back pain, massage for pain, and Tai chi for “balance and strength.”

On the other hand, aren’t most people expecting more for their “CAM” dollars? Can’t guided imagery, for example, recruit lymphocytes to fight cancer? Doesn’t massage remove toxins and “increase cytotoxic capacity“? Can’t intercessary prayer improve outcomes of serious diseases? Isn’t spinal manipulation also for health maintenance and for treating ADHD, asthma, infantile colic, otitis media, and many other problems? The Mayo Clinic Book of Alternative Medicine offers no straight answers—if it offers answers at all—to such questions.

The book has a system of “stop-lights” to let readers know whether it considers various methods to be “generally safe for most people to use, and studies show it to be effective” (green), “use the therapy with caution” (yellow), or “not to use the treatment or to use it very carefully and only under a doctor’s supervision” (red). The last recommendation is repeated throughout the book:

Even when a green light is present, it’s still important that you discuss the treatment with your doctor and use it appropriately.

Hmmm. Readers are also told in this book that “a naturopathic physician is a primary health care provider trained in a broad scope of naturopathic practices in addition to a standard medical curriculum” (the straight answer: No), and will have been assured elsewhere that “The proper title for a doctor of chiropractic is ‘doctor’ as they are considered physicians under Medicare and in the overwhelming majority of states.”

Let’s briefly look at the book’s discussions of a few methods.

Acupuncture

The book gives this Top Tenner a “shining green light”:

Our Take

Acupuncture has been used at the Mayo Clinic since the 1970s. Mayo Clinic has licensed acupuncturists on staff. When performed properly by trained practitioners using sterile needles, acupuncture has proved to be a safe and effective therapy. A review of acupuncture by the World Health Organization found it was an effective treatment for 28 conditions and there was evidence to suggest it may be effective for several more.

The straight answer: No.

Chiropractic

The “Hands-on Therapies” chapter was written by Ralph Gay, MD, DC. Here is his entire description of the conceptual basis of chiropractic:

Chiropractic treatment is based on the concept that restricted movement in the spine may lead to pain and reduced function. Spinal adjustment (manipulation) is one form of therapy chiropractors use to treat restricted spinal mobility. The goal is to restore spinal movement and, as a result, improve function and decrease back pain.

Dr. Gay has somehow omitted any mention of the central dogma of chiropractic: the subluxation. He is aware of it, of course; elsewhere he calls it “a good theory.”

Here, Dr. Gay comments on reflexology:

Among most conventional doctors, the theory behind reflexology is a little difficult to grasp.

Uh, no kidding, but that doesn’t stop him from asserting that “preliminary evidence” for reflexology reducing menopause symptoms requires “further research.” What the hay, asks Dr. Gay, “Why does any form of treatment work?”

Energy Therapies

Nurse Susanne Cutshall informs us that

Energy based therapies may be among the most controversial practices because of the difficulty in convincingly using any biophysical means to measure the effects of some therapies. However, active investigations are being conducted at academic medical centers, including Mayo Clinic, and energy medicine, in general, is gradually gaining popularity.

Ah, the magical effects of the euphemism (“difficulty”), the pseudoscientifc (“biophysical means”), the weasel words (“convincingly,” “some”), and the bait-and-switch (“active investigations” begets “popularity”). You won’t learn, in this discussion, of the diffculty in convincingly using any human means to measure the effects of some therapies.

Homeopathy

Rheumatologist Nisha Manek discusses “other approaches”: Ayurveda, homeopathy, naturopathy, and Traditional Chinese Medicine:

Treatments that comprise alternative medical systems focus on prevention and on achieving a healthy ‘balance.’ They promote diet, exercise, sleep, and daily routines to maintain wellness and encourage healing.

Jeez, there musta been something other than their alternative medical systems to explain why China and India have suffered from terrible plagues and other ills, even within the last few decades. Not to put too fine a point on it.

What about those medical systems that we honkies can call our own? We’ve already heard from the Mayo regarding naturopaths. Homeopathy gets a “yellow light” (how responsibly cautious!):

Homeopathic medicine is popular. However, it lacks good studies to prove its effectiveness. Studies that have been done have generally been small and have produced conflicting results. In general, the scientific community also finds the theories on which homeopathic medicine is based questionable and difficult to accept. These factors have kept it from being widely accepted into mainstream medicine.

Phew. Such language—with its suggestion that it is the lack of good studies that holds homeopathy down, its implicit call for more studies, its coy suggestion that it isn’t so much that the “theories are questionable” but that the scientific community is, well, too closed-minded to accept them—is so prevalent in this book that it makes me weary, so let’s quickly wrap this up. The straight answer: No.

The Need to Obfuscate

I should mention that not every method discussed in this book is given a green or even a yellow light. I can imagine that proponents are accusing me of selective quoting, and that’s true to an extent. It is a justifiable extent, however, because what I’ve discussed is more than sufficient to disqualify the Mayo Clinic authors from any claim to responsible reporting.

What’s most noticeable about the tone of the book is it’s ponderous, ditzy blandness (if there is any hope that woo-philic readers will tire when they finally realize that they are being treated like small children, this book will be invaluable). Such blandness, of course, is common to apologetic, quackademic expositions. So are the misleading language devices mentioned above (and more: chiropractic becomes “chiropractic care”; homeopathy becomes “homeopathic medicine,” which “seeks to stimulate the body’s ability to heal itself by giving small doses of highly diluted substances [that] are derived from natural substances,” and so forth).

“Today’s New Medicine,” as the Mayo book also calls it, is thus new because, well, it’s promoters call it “new“. No surprise that the authors tout the Bravewell Collaborative’s Consortium of Academic Health Centers for Integrative Medicine, a great wellspring of Quackademic Newspeak. But we’ve known that the Mayo Clinic has been in bed with Bravewell for years.