It is so easy to be wrong – and to persist in being wrong – when the costs of being wrong are paid by others.

— Thomas Sowell

We are in unprecedented times. This may come as a shock for those who haven’t interacted with civilization since March, but the pandemic will be around for a while; effective vaccines and treatments are still likely months away. Even in our modern scientific era, our current prevention and mitigation strategies for keeping the SARS-CoV-2 virus at bay are not much better than we employed over a century ago during the 1918 H1N1 pandemic. Self-isolation, social distancing, hand washing (and other personal hygiene measures), and mask wearing are the best weapons we have to slow down the spread of this virus at the moment. The world is watching in suspense as the scientific method is utilized in real-time to safely and expeditiously create the desperately-needed vaccines and therapeutics.

Much has been written about the pandemic and how communities and individuals are navigating the confusing and ever-changing information and recommendations put forth by experts and non-experts alike. In this article, we would like to zero in on some of the factors that affect people in their everyday lives; namely, why masks are important and effective, the psychology behind mask non-compliance, and how to communicate the importance of mask wearing with the public, our friends, and our families.

The science of masks as a covid-19 mitigation effort

There are three ways to manage the spread of infectious diseases from a public health perspective:

- Prevention, largely through wide-spread vaccination to achieve herd immunity, clean water, sanitation measures, etc.

- Effective therapeutics to minimize mortality, shorten disease duration and sustained adverse effects.

- In the absence of a vaccine or effective treatments, the tactic of last resort is behavior modification.

Unfortunately, with the emergence of the SARS-CoV-2 virus that caused the COVID-19 pandemic, the world has been forced to employ option # 3 – behavior modification – until the science catches up and provides us with a vaccine and/or an effective treatment.

At the onset of the pandemic, behavior modification focused on hand hygiene, cough etiquette, and disinfection of surfaces to reduce transmission through fomites (an object or material that can become contaminated and transmit infection). When these proved ineffective in making a substantial impact on viral spread, social isolation and social distancing was deemed necessary, and voluntary compliance was encouraged. The science behind these efforts was largely based upon our knowledge of mitigating transmission of the influenza and other viruses, due to lack of evidence and experience about the novel coronavirus itself.

At that time, masks were not recommended for the general public, in part, to conserve scarce PPE needed for front-line healthcare workers. Moreover, the rationale was that, like influenza, the disease was largely spread through droplets (5-100um) generated through coughing and sneezing. Such large droplets quickly succumb to the effect of gravity, and fall to the ground or other surfaces. Over time, however, it became apparent that the role of aerosols, which are smaller than droplets (<5um), generated through breathing and speaking was greater than initially anticipated. Moreover, we learned that the viral aerosols can spread from pre- or asymptomatic patients. These aerosols can be sustained in the air for several hours, especially in environments that lack robust ventilation. This means that in addition to continued social isolation, something that had been wearing thin on the psyche of the nation, another tactic was necessary. The solution: widespread use of masks.

The effectiveness of masks can be seen in other countries that quickly implemented mask usage. The most rigorous example is Taiwan, where the spread of COVID-19 remained low (411 cases and 7 deaths as of May 21, 2020, with a population of 24 million) in spite of lack of social isolation because universal mask usage was implemented early and comprehensively. This early success has persisted; as of 15 October 2020, the total cases for the country remain low at 531, with still only 7 deaths – quite an impressive public health feat.

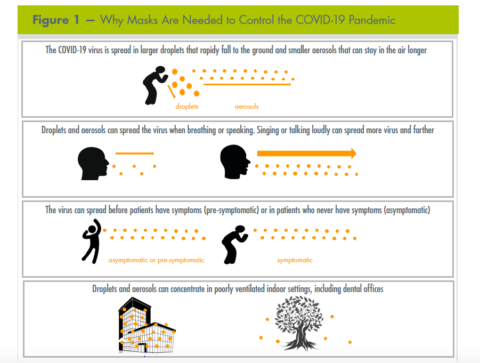

This new knowledge led to the CDC and the WHO recommending widespread mask usage, including homemade cloth masks, as masks can reduce the number of viral particles spread throughout the surroundings with each breath, reduce the likelihood and severity of COVID-19 illness, and protect uninfected individuals from aerosols and droplets. It is particularly important to wear a mask in indoor areas that can accumulate high concentrations of aerosols, including healthcare settings. Figure 1 presents talking points that can be used when addressing the need to wear masks.

FIGURE 1: Why masks are needed to control the covid-19 pandemic

Factors that influence compliance with mask utilization

An individual’s decision to wear – or not wear – a mask during the current pandemic no doubt is also influenced by many complex factors. Among some of the influencing factors are the role of social identity (a social factor), heuristics (a neurological factor), and cognitive dissonance (a psychological factor). Following is a description of these factors and how they may be influencing compliance with mask usage.

Social Identity

As humans evolved, being part of a social group had a great influence on survival and progress. The benefits of being part of a social group were significant, including protection, division of labor, shared resources, bonding, and a sense of belonging. Being alone and isolated was a death sentence, so we have an innate drive to join groups and oppose other groups in times of conflict.

In essence, being part of a group becomes part of one’s identity. In contemporary times, the context of social identity is less about physical proximity and physical protection, but rather is more of a social network and a way of thinking. This can create a bias toward accepting and believing things that are consistent with one’s perceived social group rather than accepting facts supported by evidence. The sense of belonging remains so important – and the costs of isolation so great – that belonging becomes more important than being correct.

The negative consequence of social identity thinking is that it creates an “us” vs “them” mentality, with a natural preference toward “us” rather than “them”, and the costs of becoming excluded or ostracized are great in a social context. Furthermore, in times of conflict, the sense of “us” vs “them” is amplified.

So what does this have to do with mask wearing?

As the COVID-19 pandemic emerged in the US, Shana Gadarian, a political scientist from Syracuse University, conducted a series of surveys using a nationally representative sample to understand levels of compliance with mitigation efforts such as hand washing, staying home, social distancing, and wearing masks. The studies also sought to identify demographic factors that were associated with these behaviors. The most consistent determinant of mask wearing was political partisanship – even trumping (see what we did there?) other factors such as age, zip code, gender, and education. Democrats were more likely to wear masks (73%) than republicans (53%) (the analyses were conducted within the same states so that differences in state mask mandates did not influence the results).

While behaviors such as hand washing and staying home are not as noticeable, mask wearing is. Based on the science as described above, the benefits of these practices are clear. However, when mask usage becomes politicized, the social costs with mask usage (or non-usage) become greater. These costs impact one’s social identity, resulting in a perceived or real social loss when wearing a mask in public. The mask (or lack thereof) becomes a de facto “Scarlet M” branded upon one’s face.

At the onset of the pandemic, the uncertainty level was extremely high largely because this was a novel virus and the public health and medical communities were still learning about the virus and making recommendations based on incomplete information. Now, more than 9 months later, there have been significant strides in knowledge about the virus, but we are still largely in a position of uncertainty. Not having a uniform message from those leading the nation’s pandemic efforts creates a situation where individuals are forced to make a choice on whose viewpoint to value or trust, and the tendency is to place greater value on the messaging from political leaders than the scientific experts (recall the perspective that it is evolutionarily more beneficial to be part of a social group than to be correct). Furthermore, having groups that are polarized to not trust the other side has amplified the politicization of mask wearing. Over time, the mask has become a banner to signal to others which in-group an individual belongs to.

Heuristics

In order to reduce the constant burden of decision making, our brains use heuristics to help us navigate the complicated landscape of everyday life. A heuristic is a “mental shortcut that allows an individual to make a decision, pass judgment, or solve a problem quickly and with minimal mental effort”. Heuristics are necessary tools to prevent “paralysis by analysis”, but there are corresponding liabilities to taking such short cuts, which can result in incorrect judgments, decisions, and actions.

There are several types of heuristics which could come into play when someone makes the choice to wear a mask or not. One is called the “anchoring heuristic“, in which a person places more significance on the first piece of information they receive. This typically occurs with numerical figures, but can also apply to non-numerical data. For example, if a person initially reads a believable article or watches a compelling video about the harms of mask wearing, this will be the “anchor” on which subsequent information is evaluated. If the first quantity of information is accepted as true (even if it isn’t), any new information that contradicts the original data is summarily accepted as false (even if it isn’t), leading to a vicious cycle of confirmation bias (more about that below). The fact that early on in the pandemic public health leaders did not recommend masks contributes to this anchoring heuristic.

Another is called the “representative heuristic”, where information is categorized by what the person generalizes about other, similar information. For example, a person may say “masks aren’t required for everyone during flu season, therefore they aren’t necessary now.”

Motivated reasoning (or motivated cognition) refers to an individual’s propensity to evaluate and accept a claim which favors or confirms a previously held position. This “confirmation bias” can involve the cherry picking of data and information; the individual amplifies information which agrees with his or her belief while minimizing or ignoring data which refutes said beliefs. This explains why a patient may believe a random person on YouTube rather than a consensus of experts on a given topic. For example, because a patient identifies with a “tribal” group that refuses to wear masks, he/she might deny any statistics or data which goes against his/her belief or is conveyed to him/her by a member of a different “tribe”.

Another effect is that of “immediacy”. When someone refuses to wear a mask, the effects of that choice cannot be readily demonstrated. If the individual, for example, is shopping in a public place without a mask, he/she will likely never know if he/she infected anyone. There is no immediate feedback, so any consequence is not registered in that person’s mind. If that same person happened to infect a susceptible individual who subsequently became ill or even died, he/she would never know the devastation caused. With mask wearing (or fluoride or vaccines), the consequences of following or not the scientific guidelines aren’t usually immediately apparent.

Cognitive dissonance

In their book Mistakes Were Made (But Not By Me), Tavris and Aronson discuss the phenomenon of cognitive dissonance, a term coined by social psychologist Leon Festinger in 1957. Called “the engine of self-justification”, cognitive dissonance can be defined as the psychological tension that arises when one acts in a way that is inconsistent with one’s beliefs or knowledge. This tension must be resolved somehow, and our brain will contort itself into all sorts of self-deceptions and rationalizations in order to be at peace with itself. The most common example is smoking: almost all smokers know that what they are doing is unhealthy, yet they continue. How can they rationalize their desire to be healthy (or their image of themselves as a healthy person) while smoking? In this case, the individual might say to herself “Smoking helps me lose weight, which is healthy” or “My aunt smoked a pack a day for 60 years and she’s still fit as a fiddle”. The human brain is capable of impressive feats of cognitive gymnastics.

For those opposed to mask wearing, the tension may take on an internal debate like this: “I am a kind and considerate person. I do not want to endanger anyone, and I may spread disease if I do not wear a mask. How can I justify not wearing one?” Such conversations occur beneath the level of consciousness, but the conflict is real and continuous for many issues within all of us. The resolution for a mask opponent may take the form of “I know I’m not sick, so I’m not going to infect anyone” (conveniently ignoring that asymptomatic spread is common), or “It’s a violation of my rights to force me to wear a mask. If someone doesn’t want to get infected, then they should just stay home”. This self-justification removes individual responsibility and shifts it onto others.

Discussing mask compliance

This article’s irony is that we discuss how information alone isn’t useful in changing behavior while hoping that the reader will change their behavior based on the information we are providing. So can we change behavior? Initiating change requires communication strategies that will be well received. Providing correct information is essential; however, messaging can be more effective when considering the psychological factors addressed above: social identity, heuristics, and cognitive dissonance.

Communication strategies are based on two broad categories:

- Communicating with recipients of COVID-19 scientific misinformation (of which there is no shortage), and

- Engaging with those who refuse to wear a mask based on a belief that such expectations infringe upon their rights.

Regardless of the reason or the circumstance, and despite the apparent wide differences in motives, there are commonalities in the approach one can take.

Perhaps it is best to begin with what not to do. When someone holds an opposing perspective – be it about masks, a favorite sports team, or politics – the first temptation is to consider the other person’s viewpoint is wrong. Calling people out in this manner might feel good and give us a brief feeling of righteous superiority, but it is counterproductive in the long run. As soon as a person feels attacked or disrespected, they become defensive and less receptive to change.

Another approach often employed is listing all the “objective” evidence in support of a position while refuting the others. After all, if everyone just had the facts (we tell ourselves), our correct position would be obvious, right? In fact, quite the opposite is true. Decision-making for most people is influenced by new information using emotion rather than logic. In some cases, presenting good scientific evidence can actually backfire, causing the person to anchor to an erroneous belief even more firmly.

A resource for lessons on effective communication strategies is found in research on vaccine hesitancy. There, investigators found that sharing facts with hesitant parents may not be useful and can be harmful in motivating such an individual to be more steadfast in their beliefs. What researchers did find persuasive was messaging from peers, even more so than from experts. Consequently, showing graphs, charts, and statistics around vaccines – or masks – may make us feel knowledgeable and confident, but it is usually not convincing for doubters.

In order to be persuasive, one must employ the tools of empathy and narrative. Just as a picture is worth a thousand words, a story is worth a thousand graphs. Our recommendation is to start by trying to find common concerns and values to grow the conversation.

For example, in talking to a non-mask wearer, one may start the conversation with “I notice that you aren’t wearing a mask. I realize that is your personal choice, and I know they can be uncomfortable and a hassle” (empathy). “But I’m concerned about my elderly parents and friends that might become infected if we aren’t careful. I read a story about an otherwise healthy 72-year-old who was accidentally infected by her asymptomatic grandchild and spent two weeks on a ventilator “. This provides a narrative with an emotional appeal – something that is more likely to change behavior than scientific evidence.

Conclusion

It would be nice if human beings based their worldviews, attitudes, and behaviors on logic and reason – running complex cognitive algorithms to determine the best course of action in any given situation – but our species is not hard wired that way. There are social, neurological, and psychological reasons that influence many behaviors. Often, emotion supersedes logic and we place a higher value on short-term pleasure or comfort over long-term benefit. Our brains can justify and rationalize just about anything we do or think if it makes us feel better about ourselves, relieves internal psychological tension, or allows us to achieve a goal. Moreover, our brains take cognitive “shortcuts” which allow us to complete tasks and solve problems quickly by rote and repetition. And we are influenced by our peers, and seek to be in compliance with others who are like us. All of these cranial “hacks” are useful – even necessary – in the right situations, but they can make us vulnerable to cognitive errors and mental mistakes.

Even if we could reduce our world to a series of calculations and analyses, the time and energy costs necessary to do so would literally prevent us from living our lives. There is simply too much sensory and informational input bombarding us to continuously perform so many cranial calculations. That is why we humans often make decisions that defy valid scientific information and cause us to behave in ways that are against the best interests of ourselves and society. Some of us smoke against our better judgement. Some of us eat unhealthy foods and don’t exercise as we should. And some of us refuse to wear masks.

Using communication strategies geared toward mask usage that appeal to emotions, rather than facts, and perhaps providing examples promoting use of masks from an opponent’s social community are likely to be more effective in changing behavior. To be effective, find shared values, and use narratives that create emotional responses to motivate positive change in mask-wearing behavior.

This article was originally published in the Journal of the Michigan Dental Association and has been modified for the Science Based Medicine readership and reposted with permission. The lead author of the paper is Dr. Julie Frantsve-Hawley.

Dr. Frantsve-Hawley is the director of analytics and evaluation at the DentaQuest Partnership for Oral Health Advancement. She has extensive experience in evidence-based health care, medical and dental research, analytics, implementation science, scientific publishing, and advocacy. She has served as the Executive Director of the American Association of Public Health Dentistry. She received her PhD from Harvard University’s Biological and Biomedical Sciences program.

The Mask Ask: Understanding and Addressing Mask Resistance

The wearing of masks has become contentious on scientific and ideological grounds. Why is that, and how can we communicate with people who don’t follow the scientific guidelines?