Ever since antivax activist turned independent Presidential candidate Robert F. Kennedy Jr. suspended his Presidential campaign to bend the knee to Donald Trump in return for a high-ranking position in his administration should he win, coining the term “make America healthy again” (MAHA) as a direct riff on Trump’s “make America great again” (MAGA) slogan, we’ve been faced with the consequences the possibility, later becoming the reality, of putting a conspiracy mongering, antivax, alternative medicine crank in charge of all non-military federal medical, public health, and biomedical research programs. Now that RFK Jr. is Secretary of Health and Human Services, we have seen the consequences of letting RFK Jr. “go wild on health,” “go wild on the food,” and “go wild on the medicines,” as Trump promised during the campaign, and it’s not good, particularly for vaccines, as I’ve written about extensively. However, what I haven’t written about so much is how the other vibes-based, unscientific ideas behind MAHA could end up reshaping medicine. For example, leaving aside the extreme antivax views of our HHS Secretary—and, make no mistake, he is antivax to the core and coming for your vaccines—one aspect of MAHA is its embrace of a form of alternative medicine known as “functional medicine” (FM), as embodied in one of RFK Jr.’s key allies in MAHA, previously little-known physician named Dr. Casey Means, who is Donald Trump’s nominee for Surgeon General.

It’s been a long time since I’ve written about functional medicine, which used to be a common topic on this blog back in the pre-MAHA ancient past. However, given that our next Surgeon General is likely to be a functional medicine quack, I thought that now was as good a time as any to revisit the topic of functional medicine, in particular because Means is not the only force that is likely to work to legitimize functional medicine. Before I write about Dr. Casey Means, what functional medicine is, why it’s quackery, and why MAHA likes it so much, let me point to an announcement from last month by the Institute of Functional Medicine (IFM). Here’s part of the press release:

The Institute for Functional Medicine (IFM) today took the next step in the new Functional Medicine Certification Program™ by announcing the formation of the International Board of Functional Medicine Certification (IBFMC)™. Established by a formal resolution of the IFM Governing Board of Directors (BOD), IBFMC™ is the first-ever certifying board for functional medicine and operates autonomously to oversee and set standards for the Functional Medicine Certification Program™ (Certification Program).

“Aligned with IFM’s mission to ensure the widespread adoption of functional medicine, the IFM Governing Board of Directors is proud to establish this autonomous body to lead the new Certification Program,” said Dr. Gail C. Christopher, chair of IFM BOD. “IBFMCTM ensures proper oversight on the assessment of practitioner competencies in functional medicine through their successful completion of the industry-leading Certification Program for the field of functional medicine.”

I always laugh when I read something like this. After all, how does one determine what the core competencies and core knowledge are in a quack specialty? (Imagine the same thing for homeopathy.) Some of you out there might think I’m being unfair and too harsh throwing around the q-word as I’ve been doing, but, as you will see, while FM does include some science- and evidence-based bits (as in some of the stuff about nutrition), these morsels of non-quackery mostly serve as seasoning to disguise the flavor of all the massive overtesting, overtreatment, and embrace of quackery like homeopathy and acupuncture, all in the name of “holistic” medicine. Moreover, as we’ve long documented here at SBM, one of the favored techniques that quacks use to slather on a patina of seeming legitimacy onto an edifice of quackery is the formation of what Dr. Kimball Atwood dubbed way back in 2008 “pseudo-professional organizations,” some of which form pseudo-professional boards in order to grant practitioners of quackery pseudo-certifications in various quack practices. (Naturopathy as a “specialty” has been particularly effective using this technique.) This “board certification” for FM is just the most recent of which I’m aware, and, truth be told, when I learned about the IFM certification, I was rather surprised that the IFM had never done something like before.

I note here, as I do whenever I see one of these “wholistic” or “integrative”-style “board certifications,” that this is not a board certification granted by one of the boards falling under the American Board of Medical Specialties, such as the American Board of Internal Medicine or the American Board of Surgery. It is mainly certifications from boards that fall under the ABMS that are recognized by hospitals, insurance providers, etc. as allowing a physician to be considered “board certified” in a specialty.

Let’s start with who Casey Means is and how she embraced functional medicine before I explain why that is a problem and what her elevation to surgeon general and the MAHA embrace of FM could mean for medicine.

Casey Means, MD: A conversion story

As is the case for many conventional doctors who “go rogue” and embrace “wholistic” medicine that is largely not science- or evidence-based, Dr. Means’ story sounds a lot like a religious conversion story. I find it useful to go to her website and quote it from the horse’s mouth, so to speak. Here is how Dr. Means describes her journey, in which she quit her otolaryngology residency during its final year in order to embrace “wholistic” medicine, when she was just months away from being board-eligible as an otolaryngologist:

After completing four years of surgical residency in Otolaryngology–Head and Neck surgery, Dr. Means resigned from her residency in late 2018 to focus on reforming the “sick care” paradigm in American healthcare. Her work centers on introducing a systems-thinking perspective to clinical medicine, highlighting the interconnected physiological root causes of many of the most common Western chronic diseases. After being awarded a full medical license in Oregon in 2018, she opened a private practice in Oregon in early 2019 focusing on holistic health and functional medicine, called Means Health.

In an aim to scale functional medicine principles and nutritional awareness to a wider population, she co-founded the health company Levels in late 2019, which empowers individuals to monitor and understand their key metabolic biomarkers, aiming to increase awareness of factors that contribute to the most common and preventable diseases in the United States. The company’s stated mission is to “reverse the metabolic disease epidemic,” and since 2022 has undertaken an Institutional Review Board-approved research study of over 10,000 participants to characterize glucose patterns in a non-diabetic population to better understand the transition from healthy glucose levels to overt metabolic dysfunction.

I can’t help but cringe at some of the language, which should be very familiar to readers of this blog. As you will see, FM docs love to claim that they are engaging in “systems-level thinking” (as opposed, obviously, to those of us who supposedly engage in that horrible “reductionist” scientific thinking) and addressing the “interconnected physiological root causes of many of the most common Western chronic diseases” (as opposed to those of us who supposedly only treat the symptoms and not the “root cause” of diseases). It’s a false dichotomy that I’ve long detested: The alternative medicine claim that one must embrace woo in order to practice “wholistic” medicine. True, she doesn’t say this (exactly) in this passage, but the attitude is there. Unlike the unimaginative and boring doctors trying to apply evidence-based medicine to patients, she is the bold maverick embracing a much more complex and “systems-level” way of thinking. In her bio, she brags repeatedly at her scientific accomplishments, and, I must admit, they are indeed impressive for a young investigator. However, as is almost always the case with “brave maverick” doctors like Means, pretty much all of these impressive accomplishments took place before she left conventional medicine to embrace FM.

In addition, in her book Good Energy, Means recounts the story of her mother’s death from pancreatic cancer, as described in this New Yorker article:

The second was the death of Gayle Means, in January, 2021, at the age of seventy-one, from what Casey calls a “preventable metabolic condition,” also known as pancreatic cancer. Casey depicts her mother as active and watchful of her health: she got her preventive tests at the Mayo Clinic, saw doctors at Stanford, ate mindfully, and exercised regularly. But she was also a former smoker, and, like many seniors, took metformin to manage her blood sugar and a statin for cholesterol. On the eve of the pandemic, mother and daughter visited Sedona, the New Age destination in Arizona, for what Casey describes as “‘Dr. Casey’s Bootcamp’ of proven actions to improve metabolic health: extended fasting, cold plunging, exercise, morning sunrise hikes.” Gayle, her daughter says proudly, “was actually very much on the same page about, sort of, holistic health as me.”

About a year later, according to Casey, her mother felt fatigue and stomach pain while on her daily hike. After getting blood work and a CT scan, she received a diagnosis of Stage IV pancreatic cancer, via text message. Casey got a FaceTime call from her mother, she writes, in which “she told me that she was dying, that she had to leave me, and that she would not meet my future children.” She had “softball-sized tumors all throughout her belly.” Thirteen days later, Gayle Means died. In “Good Energy,” Casey rues the fact that her mother “didn’t have the resources to make sense of her biomarkers.” Still, her final days, Casey said in 2022, added up to “a very beautiful, transformational experience”—a “spectacular two weeks” for the Means family, in which Gayle experienced “pure joy.”

A physician should know that, alas, there are no reliable “biomarkers” that will allow pancreatic cancer to be diagnosed early. Sadly, the majority of pancreatic cancer patients present late, like Casey’s mother Gayle. However, in the story you can see the regret, the very real human physician’s belief that if only she had done something different maybe her mother would still be alive. I myself have experienced that same feeling thinking back over the death of my father this year and the ongoing deterioration of my mother’s health. Again, the above stories are the sorts of stories we hear frequently from physicians who convert to alternative medicine and quackery, that “something” led them to see all that is supposedly wrong with evidence-based medicine, a realization that led them to convert to something that they saw as better, more “holistic,” more able to take care of patients. Here is how she further characterizes her “conversion” to FM:

As her residency progressed, however, Means grew increasingly disillusioned with the reactive “sick care” model she encountered in her clinical practice. This shift in perspective led her to take time away from her surgical training to explore the intersection of holistic health and surgery. Extensive documents and emails from this period show a prolonged effort to merge her surgical work with a holistic and “root cause” approach, securing meetings with the Chief Wellness Officer at Cleveland Clinic, faculty from National University of Natural Medicine, the Casey Health Institute (which has developed an integrated approach to healthcare blending complementary and conventional therapies), and many other experts for guidance on opportunities to design and foster a more proactive and holistic practice within the surgical ecosystem. Ultimately, she felt so disillusioned with the practice and incentives of surgical care that she chose to resign and work on reform from outside the “system.”

She summarizes this in her book Good Energy,

I deeply respect doctors, but I want to be very clear on something: at every hospital in the United States, many doctors are doing the wrong things, pushing pills and interventions when an ultra-aggressive stance on diet and behavior would do far more for the patient in front of them. Suicide and burnout rates are astronomical in health care, with approximately four hundred doctors per year killing themselves. (That’s equivalent to about four medical school graduating classes just dropping dead every year by their own hand.) Doctors have twice the rate of suicide as the general population. Based on my own experience as a young surgeon, I think a contributor to this phenomenon is an insidious spiritual crisis about the efficacy of our work and a sense of being trapped in a system that is not working but seems too big to change or escape.Two weeks after resigning from residency, Means participated in a business retreat for physicians with Dr. Pamela Wible focused on designing an “Ideal Medical Practice,” beginning on October 14th, 2018. In December 2018, she obtained her unrestricted medical license with the state of Oregon, and incorporated her medical practice, “Means Health,” in January 2019, to implement a holistic and functional medicine approach in clinical practice. She began training with the Institute for Functional Medicine (IFM), completing the foundational “Applying Functional Medicine in Clinical Practice” on March 8th, 2019 and completing further coursework with IFM, and started giving talks on Functional Medicine and “food as medicine” in Portland, Oregon.

In other words, she had come to a “revelation” that somehow what she was doing in her surgical residency were the “wrong” things and that, instead of surgery and medications, she should be pushing an “ultra-aggressive stance on diet and behavior,” justifying her conversion by citing statistics showing that physicians and other health care professionals have a higher rate of death by suicide than average and attributing it to an “insidious spiritual crisis.” Whenever I see that sort of language coming from a surgeon, I always wonder: What did you expect going into a surgical specialty? Surgery is only sometimes preventative. It’s most frequently a treatment for something that’s already gone wrong, sometimes catastrophically wrong, that can best be fixed by removing or rearranging pieces of human anatomy. If a doctor is interested in holism and prevention, she should go into primary care or internal medicine rather than into a surgical subspecialty.

Unsurprisingly, reporters who have looked into what actually happened in 2018 that led Dr. Means to abandon her surgical residency so close to finishing have found that the story is…more complex…than what Means relates on her website and in her interviews. There’s an excellent report in Vanity Fair by Katherine Eban entitled “She Was Tearful About It”: The Nuances of Casey Means’s Medical Exit and Antiestablishment Origins, in which Eban interviewed fellow residents and her department chair about what had happened to lead Means to abandon her residency so close to the finish line. Remember, although there is attrition among surgical residents, it’s very uncommon for a surgical resident to quit in her last year, other than for health challenges or switching specialties, and even then the vast majority of attrition happens in the first couple of years.

There does, however, appear to be a grain of truth in Means’ characterization of her departure. Remember that part about suicides among physicians? According to the Vanity Fair article and an LA Times article, the reason that Means departed was largely due to stress and anxiety.

From the LA Times:

Dr. Paul Flint, a former chair of Otolaryngology/Head and Neck Surgery at Oregon Health and Science University, said Means resigned from the residency because of anxiety.

After four years of training, Means came to him and Dr. Mark Wax, the residency program director, and said she wasn’t sure it was the right job for her.

“She wasn’t even sure she wanted to be in medicine,” Flint said. “She wanted to do something different. She wanted to resign.”

Flint and Wax urged Means to think about it more and offered her three months paid time off.

“She was under so much stress,” he said. “She did that, came back and decided she wanted to leave the program. She did not like that level of stress.”

Flint said Means was competent, a good resident. “But there was a lot of anxiety around this,” he said of the role of the surgeon. “You become much more responsible the more senior you get.”

Don’t I know it! That’s also one very understanding department chair, to offer her three month’s paid leave to “think about” her decision, although in her book Means also says that she took the leave also to deal with neck pain.

From the Vanity Fair report:

Two former residents she served alongside offer a version of her departure from the program that matches with Flint’s. They say that contrary to Means’s oft-told version of events, she exited due to her inability to handle the admittedly high pressure. They describe her as being deeply unhappy and fearful of harming patients, and say she took a leave of absence before departing altogether. The former residents also tell VF that they do not recognize the version of events laid out in the book. In their view, Means misrepresented her residency training and proclaimed a medical conspiracy against good health that simply doesn’t exist. (Both former residents have asked not to be named because they fear retaliation from the Trump administration.)

Another resident, who was one year ahead of Means in the program and has asked not to have his name used due to restrictions imposed by his current employer, says, “I thought she handled the stress of the program exceedingly well, and that’s one of the reasons why people wanted her to stay and see it through.” He adds, “The way she explained it to me at the time, she felt it wasn’t the best fit for her, the residency in general and otolaryngology in particular. It wasn’t as fulfilling or rewarding as she expected.”

I’m about to do something a bit unexpected here and express some empathy with Means about this. I myself came very close to quitting my general surgery residency during my third year due to the stress. I even went so far as to investigate what it would take to transfer, for instance, into the pathology residency program at the hospital where I was training. With the help of an understanding chair and residency director, I didn’t resign and managed to finish my residency with good marks, but I fully understand the stress, maybe even more so, given that I trained in the era before resident work hour restrictions. It does take guts to realize so close to the finish line that you had made a mistake in your specialty choice and then actually do something about it. If Means had just said that she had changed gears because she was stressed out and unhappy with practicing otolaryngology, I’d be fine with that; I might even admire her for her choice, other than that she chose FM as her specialty.

Unfortunately, according to the Vanity Fair article:

After she left, the two former residents grew increasingly skeptical of her public claims. “I did not witness a spiritual awakening,” the former junior resident says. “It felt more and more like she was preying on the less educated and using the MD she had to tout these pseudoscience things.”

The other former resident observes, “She’s a good person and does care for people and wants what’s best. But it feels disingenuous, demonizing your training. She didn’t make it through.” The former resident adds, “By trying to question our entire field and sowing distrust in medicine, it’s hard to ignore that she may benefit from that.”

Indeed. However, sowing distrust in medicine and “reinventing” one’s “journey” to sound a lot more altruistic than it actually was are key components of any “brave maverick” doctor’s journey, as regular readers know. As you will see, that first junior resident quoted sounds pretty spot-on. For one thing, Means’ actual functional medicine practice didn’t last very long. It wasn’t long at all before she pivoted to sales of products to treat “metabolic health” and raising venture capital to do so. Since then, she has bragged about appearing on Joe Rogan’s and Tucker Carlson’s podcasts to promote her viewpoint that the chronic disease epidemic is “metabolic” and that diet and lifestyle are the answer. Part of that evangelism (and business) involves her forming a company that markets, among other questionable products, continuous glucose monitoring devices to everyone, not just people with diabetes or pre-diabetes, as a near-panacea for monitoring diet. (More on that later.)

Finally, like a lot of other “brave mavericks,” Means’ reaction to criticism, as included in her bio on her website, is very much of the “poor, poor persecuted me” variety, just like “brave mavericks,” COVID contrarians, and any others who portray valid science-based criticism as an attempt to “silence” or “cancel” them:

Responses to this widespread backlash from legacy media included articles criticizing mainstream media for their biased framing of her work, including “Rise of the “Woo-Woo” Woman: The Witch Hunt for Dr. Casey Means” by Lauren Lee, which stated that “the backlash against Trump’s pick for Surgeon General isn’t about science — it’s about a country terrified to confront its own spiritual collapse.”

Means is considered controversial because her work challenges the economic and cultural foundations of U.S. healthcare, agriculture, and food systems. She criticizes “sick care” medicine for profiting from disease management, calls for reform of the Farm Bill, pharmaceutical incentives, food culture, and industrial agriculture, and integrates spirituality, ecology, and patient empowerment into her philosophy—departures from conventional frameworks that have led some outlets to label her “unscientific.” Legacy media critics often dismiss her credibility because her message exposes institutional failures and calls for disruption, and her career trajectory has included periods without direct one-to-one patient care while pursuing work in preventative health that has reached tens of millions. Some critics cite her work as an entrepreneur and health-technology co-founder as incompatible with public health leadership, overlooking Levels’ large-scale research collaborations with academic institutions and the complex management and operational skills required to build a high-growth company. Others argue she oversimplifies chronic disease and places too much responsibility on individuals, failing to recognize that her approach explicitly advocates for both bottom-up empowerment—equipping individuals with the knowledge to understand their own bodies—and top-down systemic reform that makes healthy choices affordable, accessible, and the cultural default. Finally, her stances on medications and emerging therapies such as vaccines, oral contraceptives, and psychedelic therapies have drawn intense scrutiny, though her consistent position on each of these therapies has strongly emphasized informed consent, medical freedom, and ending corporate liability shields and conflicts of interests that often distort research findings and prioritize profit over patient well-being.

You get the idea. Like so many quacks, she portrays criticism of her as not being about the science but being because she, brave maverick that she is, “challenges the economic and cultural foundations” of medicine, “criticizes “sick care,” and “integrates spirituality, ecology, and patient empowerment into her philosophy.” I’m also amused by how she is clearly stung by criticisms of MAHA, which are quite justified, that it undermines public health and ignores the social determinants of health in favor of a model in which health is entirely a matter of one’s personal choices, where good health is a consequence of “virtue”; i.e., eating the “right” diet, engaging in the “correct” behaviors, and the like. Then, of course, she’s not anti-medicine or antivaccine; she’s just for ending “corporate conflicts of interest” and for “informed consent” and “medical freedom.” In fairness, I’m not yet sure if she’s antivaccine, if only because of some of the highly negative reaction of some prominent antivaxxers to her nomination, although a recent Washington Post article by Lauren Weber and Rachel Ruben notes that she has started questioning “the cumulation of the childhood vaccine schedule and the hepatitis B vaccine” and has asked on Joe Rogan’s podcast, ““I bet that one vaccine probably isn’t causing autism, but what about the 20 that they are getting before 18 months?”

Yes, she’ll come the rest of the way over to RFK Jr.’s antivax views soon enough.

It occurs to me right here that advocating continuous glucose monitoring devices for almost everyone as a means of improving health is so very, very functional medicine. Indeed, the entire program offered by her company Levels, is very much the epitome of functional medicine quackery. (Let’s just say that the highest “Level” program, costing $1,499 a year, involves twice a year measurements of “100+ health markers,” two months of continuous glucose monitoring, and a lot more.

On to functional medicine.

Functional medicine: The worst of conventional and alternative medicine

Over the years, I’ve frequently referred to the kludge that is known as “functional medicine” as the “ultimate misnomer” in medicine and “worst of both worlds.” What I mean by that is that FM combines the worst elements of conventional medicine, overtesting and overtreatment involving reams of questionable lab tests and imaging studies (many not reimbursed by health insurance), with the worst elements of alternative medicine, specifically embracing quackery like naturopathy and acupuncture and “integrating” them with medicine. Indeed, I’ve often riffed a major punchline in a famous Mitchell & Webb comedy sketch about homeopathy and referred to FM as “reams of useless tests in one hand, a huge invoice in the other.” Even if you don’t know anything about FM, you can get the feeling that overtesting is a key component of it just from realizing that Means’ plan offers to look at 100+ biomarkers drawn twice a year. Unsurprisingly (to anyone who knows anything about FM) this sounds very similar to a panel of 100+ tests offered by one of the longtime gurus of FM, Dr. Mark Hyman, who himself was (prepandemic, at least) a frequent topic of this blog. Unsurprisingly, Dr. Hyman is himself tight with RFK Jr., a longtime buddy, and promoting FM as part of MAHA.

But what is functional medicine itself? It is a “specialty” that was “pioneered”—actually more or less made up of whole cloth—by Dr. Jeffrey Bland, who co-founded IFM, and then championed by people like Dr. Mark Hyman, who is quoted as characterizing FM thusly:

Dr Hyman, a medical doctor, says FM is “a rigorous system for assessing chronic illness using new advances in systems biology and systems thinking”.

“Functional Medicine is not about a test or a supplement or a particular protocol,” he adds. “It’s really a new paradigm of disease and how it arises and how to restore health. Within it there are many approaches that are effective, it’s not exclusive, it doesn’t exclude traditional medications, it includes all modalities depending on what’s right for that patient.”

We’ve asked (and tried to answer) the question of what FM is many times on this blog going way, way back to Wally Sampson’s posts explaining why FM is quackery. (Even 17 years later, I like his characterization of FM as an “indecipherable babble and descriptive word salad.“) Basically, FM invokes “systems” thinking in order to make it seem as though it is more “holistic” than conventional medicine. Oddly enough, however, when Dr. Hyman used to discuss the systems biology of autism, he made no sense and mangled the science; ditto for cancer.

Is that too harsh? I don’t think so. I’ll explain why by first taking a look at the “functional medicine model.” Hopefully longtime readers will forgive me if this is a bit repetitive of what I’ve written before, but I do feel the need every so often to reiterate our objections to functional medicine without forcing you to click on multiple links. In other words, every few years I like to lay out why FM is quackery in another post. Looking over the IFM website, I can’t help but note that a lot of what used to be public information is now either restricted content on members-only pages or otherwise unfindable. A lot of it seems to have been incorporated into a series of courses, some free, most paid. So I will use Archive.org when needed, for example, to refer to this page What Is Functional Medicine? First, here are FM’s main principles:

Functional medicine is personalized medicine that deals with primary prevention and underlying causes instead of symptoms for serious chronic disease. It is a science-based field of health care that is grounded in the following principles:

- Biochemical individuality describes the importance of individual variations in metabolic function that derive from genetic and environmental differences among individuals.

- Patient-centered medicine emphasizes “patient care” rather than “disease care,” following Sir William Osler’s admonition that “It is more important to know what patient has the disease than to know what disease the patient has.”

- Dynamic balance of internal and external factors.

- Web-like interconnections of physiological factors – an abundance of research now supports the view that the human body functions as an orchestrated network of interconnected systems, rather than individual systems functioning autonomously and without effect on each other. For example, we now know that immunological dysfunctions can promote cardiovascular disease, that dietary imbalances can cause hormonal disturbances, and that environmental exposures can precipitate neurologic syndromes such as Parkinson’s disease.

- Health as a positive vitality – not merely the absence of disease.

- Promotion of organ reserve as the means to enhance health span.

In pretty much every post about functional medicine that I’ve ever written, I feel compelled to remind our readers that the very first principle is, in essence, functional medicine’s “get out of jail free” card for basically anything its practitioners want to do. FM docs can always find reasons, whether science-based or not, to justify any form of treatment, be it science-based or quackery, simply by invoking the “biochemical individuality” of the human being they are treating. I feel compelledto remind my readers yet again of my favorite retort to this claim: Yes, human beings are individuals, and each human being is unique. However, we’re not so unique that our bodies don’t all work pretty similarly. In other words, in terms of biology, physiology, and yes, systems biology, we human beings are far more alike than we are different. If that weren’t the case, modern medicine, developed before we had the tools to probe our genetic, metabolic, and biochemical individuality, wouldn’t work as well as it does.

FM fetishizes “biochemical individuality,” not so much because humans are so incredibly different that each one absolutely has to employ a totally different treatment for a given disease or condition in any given individual. We’re not. Nor am I arguing that the insights scientists have derived from genomics, metabolomics, and proteomics, which have revealed different system-level biochemical and metabolic pathways in physiology, don’t matter. They do. We’re just not as radically “individuals” on a biochemical basis as FM docs try to argue. In essence, FM fetishizes biochemical “individuality” because emphasizing such “individuality” distinguishes functional medicine as a brand distinct from conventional science- and evidence-based medicine and, I suspect, because it makes its practitioners feel good, like “total” doctors who are never at a loss for an explanation for a patient’s symptoms or clinical condition and can always think of more tests to figure out a problem. It also patients feel special and that their every bit of “individuality” is being catered to. As for the last bit about FM being a “science-using” profession, FM “uses” science more as a means of justifying whatever its practitioners do rather than guiding them to scientifically-proven treatments.

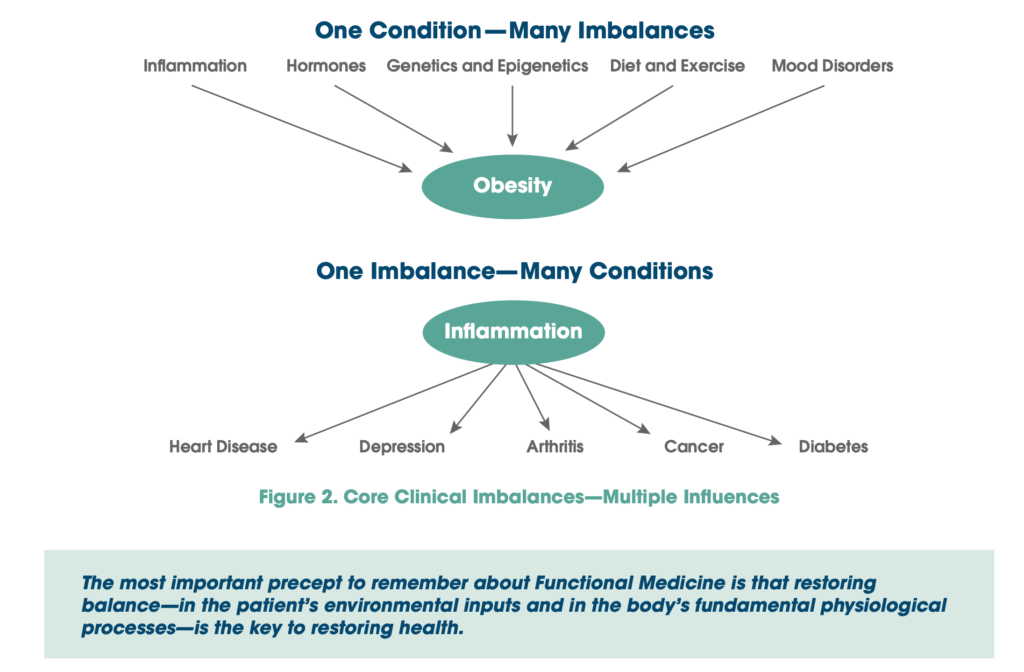

Also, functional medicine is all about the “imbalances”:

Functional medicine is anchored by an examination of the core clinical imbalances that underlie various disease conditions. Those imbalances arise as environmental inputs such as diet, nutrients (including air and water), exercise, and trauma are processed by one’s body, mind, and spirit through a unique set of genetic predispositions, attitudes, and beliefs. The fundamental physiological processes include communication, both outside and inside the cell; bioenergetics, or the transformation of food into energy; replication, repair, and maintenance of structural integrity, from the cellular to the whole body level; elimination of waste; protection and defense; and transport and circulation. The core clinical imbalancesthat arise from malfunctions within this complex system include:

- Hormonal and neurotransmitter imbalances

- Oxidation-reduction imbalances and mitochondropathy

- Detoxification and biotransformational imbalances

- Immune imbalances

- Inflammatory imbalances

- Digestive, absorptive, and microbiological imbalances

- Structural imbalances from cellular membrane function to the musculoskeletal system

Imbalances such as these are the precursors to the signs and symptoms by which we detect and label (diagnose) organ system disease. Improving balance – in the patient’s environmental inputs and in the body’s fundamental physiological processes – is the precursor to restoring health and it involves much more than treating the symptoms. Functional medicine is dedicated to improving the management of complex, chronic disease by intervening at multiple levels to address these core clinical imbalances and to restore each patient’s functionality and health. Functional medicine is not a unique and separate body of knowledge. It is grounded in scientific principles and information widely available in medicine today, combining research from various disciplines into highly detailed yet clinically relevant models of disease pathogenesis and effective clinical management.

Functional medicine emphasizes a definable and teachable process of integrating multiple knowledge bases within a pragmatic intellectual matrix that focuses on functionality at many levels, rather than a single treatment for a single diagnosis. Functional medicine uses the patient’s story as a key tool for integrating diagnosis, signs and symptoms, and evidence of clinical imbalances into a comprehensive approach to improve both the patient’s environmental inputs and his or her physiological function. It is a clinician’s discipline, and it directly addresses the need to transform the practice of primary care.

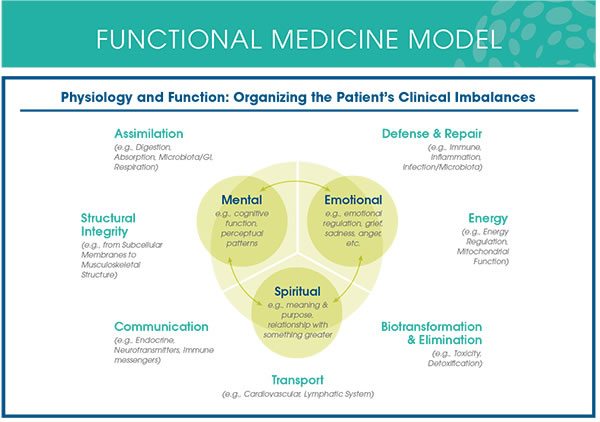

No. It is not a clinician’s discipline, and it does not address the “need to transform the practice of primary care.” Also, does the focus on “imbalances” remind you of anything? How about “imbalances” in the four humors? Or “imbalances” in the Five Elements in traditional Chinese medicine. Basically, functional medicine also fetishizes “balance” in a way that sounds very much like both ancient Asian and European medicine. Indeed, if you read much about FM from its advocates, you’ll soon find images like this one:

diagram actually means something.

Or this one:

Can you see why I sometimes compare FM to the four humors in humoral medicine or the Five Elements in traditional Chinese medicine?

In fairness, here I generally mention that there are some things that functional medicine (sort of) gets right, although these things tend to be no different than the sorts of things every primary care doctor should be getting right anyway, such as emphasizing healthy lifestyles, good nutrition, enough exercise, adequate sleep, cessation of habits known to be deleterious to health (e.g., smoking and being sedentary). Functional medicine also claims to emphasize prevention, which is a good thing as far as it goes, but again something that good primary care doctors do anyway. Moreover, the functional version of “prevention” isn’t always in line with the SBM version of prevention. Where functional medicine doctors go so very wrong is in what Grant Ritchey once described as a major unstated premise. That premise is that functional really does address the root causes of disease better than conventional medicine. (It does not.) Worse, FM also encompasses a lot of quackery, such as acupuncture, chiropractic adjustments, naturopathy, and especially “detoxification” programs. FM medicine also includes a slew of fake diagnoses, like adrenal fatigue, chronic Lyme disease, and “heavy metal toxicity.”

Basically, FM is a triumph of marketing over science, which is why it seems so appealing on the surface. Means, like Hyman before her and Bland before him, portrays FM as a new paradigm in medicine, tossing around catchphrases and buzzwords like “systems-level,” “biochemical individuality,” the body’s “operating system,” “empowerment,” and the like, all while demonizing conventional medicine. Unfortunately, the marketing has paid off, with Hyman having founded a functional medicine institute at The Cleveland Clinic, and FM finding its way into “integrative medicine” programs at academic medical centers.

Casey Means and functional medicine

Now that you know a bit about FM, I hope you can see why continuous glucose monitoring for even non-diabetics is the ultimate in the FM paradigm. It provides reams and reams of measurements of blood glucose that might or might not mean anything or be actionable to improve health. Basically, Means’ Levels program is FM on steroids. It includes a panel of over 100 biomarkers that includes standard labs (e.g., electrolytes and complete blood counts) plus a raft of tests that are normally only ordered when a condition is suspected. Then it adds the continuous glucose monitoring to measure basal glucose, glucose variability, and post-meal glucose dynamics. This is all fed into an artificial intelligence program that supposedly provides actionable “advanced AI insights” by way of a proprietary smartphone app.

As you might imagine, there is evidence that continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) can be beneficial in patients with type 1 and type 2 diabetes, as well as in patients with prediabetes. When it comes to the use of this technology (which is not cheap) in nondiabetics, as you might imagine, the evidence is a lot more mixed, confusing, and far from compelling, despite Means’s selling it thusly:

Over the past few years, however, interest has grown in the use of CGM among people without diabetes, driven by a desire to avoid prediabetes and Type 2 diabetes (conditions of high blood sugar), as well as to gain insights about how diet, sleep, and activity influence blood sugar levels.

For people without diabetes, a CGM offers real-time feedback on how foods and other lifestyle factors affect your glucose levels. This information can help you aim for more stable blood sugar to boost energy, improve focus, aid weight loss, prevent and manage chronic disease, and even foster longevity. Here, we explain what a CGM is, how it works, why people without diabetes might want one, and how you can get one.

“Even foster longevity”? Sounds awesome, right? But is there any good evidence for these claims for the use of CGM in healthy nondiabetics? The answer, in brief, is: Not really, with the possible exception of people at high risk for diabetes and prediabetes. The American Diabetic Association, for instance, explicitly states that there is insufficient evidence to support the use of CGM for screening or diagnosis of prediabetes or diabetes, and that FPG, HbA1c, and OGTT remain the standard of care for these purposes. Even in patients with prediabetes and metabolic syndrome, evidence is mixed, as this recent systematic review of personalized nutrition strategies points out. There is also some scattered evidence that CGM can improve cardiovascular outcomes in nondiabetics by guiding lifestyle and dietary interventions, but, again, as the ADA points out in its recommendations, CGM is a lot more expensive than the standard screening blood tests. For a discussion of CGM targeted at the lay audience, I recommend this article in NPR, which notes some of the promise of CGM while also cautioning:

Many people find the data confusing and unhelpful.

“Many people come to me and say, ‘I have been using the device for three or even 12 months, and I have all this data, but I don’t know what it means. I don’t know how to lower my blood sugar or improve it,'” Kennedy says.

People really need to be educated about what the data means, Popp agrees. But that education will go only so far because at this point, some of the data is still mysterious to scientists and doctors.

If you’re staying within a normal range, say about 70 mg/dL to 140 mg/dL, scientists still don’t understand what the peaks and troughs mean.

“There’s no real standard guidelines about what’s a good peak or a bad peak in nondiabetics,” Popp says.

Emphasis mine.

Perhaps I should write a more detailed post about CGM in the future, as this post is already long and CGM is not the main topic, but rather an indication of Means’ proclivities for FM and FM-adjacent overtesting. It is these proclivities that will, if she is confirmed—which is not entirely certain at this point, given that Sen. Bill Cassidy, who so woefully failed as a physician and a legislator by voting twice in favor of RFK Jr., once to send his nomination out of committee and to the full Senate and then voting to confirm him, seems leery—give her the strongest voice yet to promote FM quackery as the answer to all of America’s problems in public health, chronic disease, and diet, while supporting the faux legitimization of FM as a specialty by the IFM’s pseudo-board certification.

And so the process of “integrating” quackery into medicine that began nearly 35 years ago will continue apace, only turbocharged by President Trump, MAHA, RFK Jr., and, yes, Casey Means. Her conversion is, as I have described above, every bit a religious one, and, like many converts, particularly “medical apostates,” Means appears to revel in being seen as a “heretic.” Again, note her frequent characterization of standard evidence-based medicine as more of another religious sect than anything else. This is incredibly common language used in these spaces by advocates of FM, naturopathy, homeopathy, acupuncture, and lots of other forms of alternative medicine, as is the citation of a “spiritual crisis” as a reason for abandoning evidence- and science-based medicine. They don’t call it that, of course. Means, as does MAHA in general, seems to think that she’s following “gold standard science.” Means’ medical worldview is also largely based on fear, as so aptly described by Jessica Winter in the same New Yorker article that described Means’ reaction to her mother’s death:

The health-care system, she has claimed, is rife with “fear-based thinking,” and doctors “weaponize fear of death” in order to force harmful drugs and procedures on patients. A flawless commitment to diet, exercise, and sleep hygiene means nothing, she writes in “Good Energy,” if stress and anxiety are present, because a “cell living in a body experiencing chronic fear is a cell that cannot fully thrive.”

And yet, for long stretches of “Good Energy,” the prescription appears to be fear. Fear of Smartfood popcorn and Ben & Jerry’s ice cream. Fear of progestin pills and dryer sheets and unfiltered shower water. Fear of your glucose levels, or of not knowing what your glucose levels are at any given moment. Fear of your mother’s sub-optimized mitochondria, which she passed down to you. Fear of the takeout dinners and late nights that Gayle Means enjoyed as a twentysomething living in the West Village half a century ago. (Casey cites these youthful habits as possible causes of her mother’s “metabolic abnormalities.”) The Good Energy message, in the main, is that if you’re afraid of everything you have nothing to fear. You cannot eat your way out of death, but you should follow the Calvinist urge to try.

Any religious conversion has to include a devil that the religion will protect you against. Unfortunately, we’re probably about to find out how much she can proselytize as Surgeon General, as well as the extreme limitations in how much FM can protect one against the demons that drive Dr. Means’ fears.