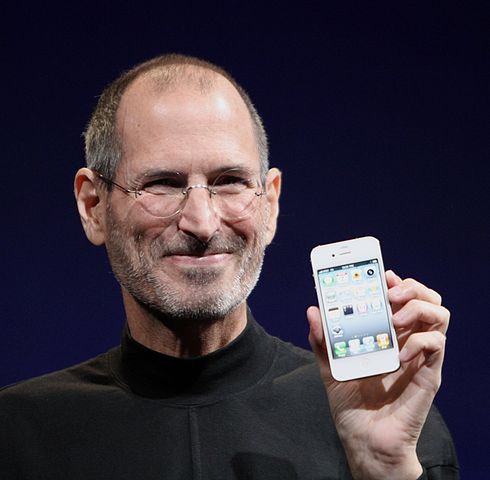

Steve Jobs in 2010

I’ve written quite a bit about Steve Jobs in the wake of his death nearly four weeks ago. The reason, of course, is that the course of his cancer was of intense interest after it became public knowledge that he had cancer. In particular, what I most considered to be worth discussing was whether the nine month delay between Jobs’ diagnosis and his undergoing surgery for his pancreatic insulinoma might have been what did him in. I’ve made my position very clear on the issue, namely that, although Jobs certainly did himself no favors in delaying his surgery, it’s impossible to know whether and by how much he might have decreased his chances of surviving his cancer through his flirtation with woo. However much his medical reality distortion field might have mirrored his tech reality distortion field, my best guess was that Jobs probably only modestly decreased his chances of survival, if that. I also pointed out that, if more information came in that necessitated it I’d certainly reconsider my conclusions.

The other issue that’s irritated me is that the quackery apologists and quacks have been coming out of the woodwork, each claiming that if only Steve Jobs had subjected himself to this woo or taken this supplement, he’d still be alive today. Nicholas Gonzalez was first out of the gate with that particularly nasty, unfalsifiable form of fake sadness, but he wasn’t the only one. Recently Bill Sardi claimed that there are all sorts of “natural therapies” that could have helped Jobs, while Dr. Robert Wascher, MD, a surgical oncologist from California (who really should know better but apparently does not) claims that tumeric spice could have prevented or cured Steve Jobs’ cancer, although in all fairness he also pointed out that radical surgery is currently the only cure. Unfortunately, he also used the failure of chemotherapy to cure this kind of cancer as an excuse to call for being more “open-minded” to alternative therapies. Even Andrew Weil, apparently stung by the speculation that Jobs’ delay in surgery to pursue quackery might have contributed to his death, to tout how great he thinks integrative cancer care is.

Last week, Amazon.com finally delivered my copy of Walter Isaacson’s biography of Steve Jobs. I haven’t had a chance to read the whole thing yet, but, because of the intense interest in Jobs’ medical history, not to mention a desire on my part to see (1) if there were any new information there that would allow me to assess how accurate my previous commentary was and (2) information that would allow me to fill in the gaps in the story from the intense media coverage. So I couldn’t help myself. I skipped ahead to the chapters on his illness, of which there are three, entitled Round One, Round Two, and Round Three. Round One covers the initial diagnosis. Round Two deals with the recurrence of Jobs’ cancer and his liver transplant. Finally, Round Three deals with the final recurrence of Jobs’ cancer, his decline, and death.

Before I start, a warning: I’m going to discuss these issues in a fair amount of detail. If you want “medical spoilers,” don’t read any further. On the other hand, one spoiler I will mention is that there was surprisingly little here that wasn’t reported before; the only difference is that there is more detail. However, the details are informative.

Round One

If there’s one thing I wanted the most information about from this biography, it was more details about Jobs’ initial presentation. After all, I had put my name on the line by arguing that his delay in surgical therapy probably didn’t make that much of a difference, and I was very curious to find out whether there was more information that would allow me to assess whether I should change my initial assessment. I was also interested in whether there was more information about what specific kinds of pseudoscience Jobs had pursued.

I was disappointed on both counts, but that’s not to say that this chapter didn’t provide me with some useful information.

The first thing I learned was the reason Jobs was getting CT scans. Remember, the diagnosis of his cancer was actually serendipitous. It was, as we like to call it, an incidentaloma in that it was an incidental finding on a scan done for a different purpose. In this case, the purpose of the CT scan was to examine his kidneys and ureter, as he had developed recurrent kidney stones beginning in the late 1990s. Jobs attributed them to his working too hard running both Apple and Pixar. In any case, in October 2003, Jobs just happened to run into his urologist, who pointed out that he hadn’t had a CT scan of his urinary system in five years and suggested that he get one. He did, and there was a suspicious lesion on his pancreas. His doctors urged Jobs to get a special CT scan known as a pancreatic scan, which basically provides a lot more detail in the region of the pancreas. He didn’t; it took a lot of urging before he did it, and when he did at first his doctors thought he had standard pancreatic adenocarcinoma, the deadly kind that few survive. As has been reported before, though, Jobs underwent a transduodenal biopsy, and the diagnosis of neuroendocrine tumor was made.

Unfortunately, no further information is provided that we didn’t already know about regarding what Jobs did during the nine months he tried “alternative” therapies. He kept to a strict vegan diet that included large quantities of fresh carrot and fruit juices. (Shades of the Orange Man!) In addition:

To that regimen, he added acupuncture, a variety of herbal remedies, and occasionally a few other treatments he found on the internet or by consulting people around the country, including a psychic. For a while, he was under the sway of a doctor who operated a natural healing clinic in southern California that stressed the use of organic herbs, juice fasts, frequent bowel cleanings, hydrotherapy, and the expression of all negative feelings.

Unfortunately, the natural healing clinic wasn’t identified. I did a bit of searching, but I couldn’t narrow down the possibilities. There’s a lot of woo in southern California. Even so, as much as many of us here would like to condemn Dean Ornish, who was Jobs’ friend, apparently Ornish did try to do right by him:

Even the diet doctor Dean Ornish, a pioneer in alternative and nutritional methods of treating diseases, took a long walk with Jobs and insisted that sometimes traditional methods were the right option. “You really need surgery,” Ornish told him.

Ornish appears for once to have been right.

There’s still more in this chapter. For example, the book states that on a followup CT scan showed that the tumor “had grown and possibly spread.” In addition, the operation that Jobs underwent was described as not being a “full Whipple procedure” but rather a “less radical approach, a modified Whipple that removed only part of the pancreas.” I can only speculate what Isaacson meant by that. A Whipple, standard or not, by definition removes part of the pancreas, specifically the head. Because of the anatomic constraints of the pancreas, the head of the pancreas usually can’t really be removed without removing a significant portion of the duodenum and the common bile duct, and often some small intestine. That’s why, by definition, a Whipple operation includes removing the duodenum and part of the intestine; if those are not removed, then it’s not a Whipple procedure. I suspect that what Isaacson probably meant was a pylorus-sparing Whipple, as I discussed before. In this operation, part of the duodenum is still removed, but not part of the stomach, as in a standard Whipple. The advantage is that a pylorus-sparing Whipple can often alleviate many of the digestive complications of a Whipple operation, such as the “dumping syndrome,” because the pylorus is preserved.

Finally, it is revealed:

During the operation the doctors found three liver metastases. Had they operated nine months earlier, they might have caught it before it spread, although they would never know for sure.

Or, on the other hand, chances are very good that those liver metastases were there nine months before. Insulinomas tend not to grow so fast that they can progress from micrometastases to metastases visible to the surgeons in that short a period of time. So, while on the surface this revelation would seem to the average lay person to indicate that Jobs’ delay very well might have killed him, in reality, thanks to lead time bias, it probably means that his fate was sealed by the time he was diagnosed. Certainly, it means that claims such as the one made by Dr. Robert Wascher are not based in science and in fact are irresponsible:

In a recent interview with Newsmax Health Wascher explained how the simple act of consuming turmeric, a natural spice popular in Asian and Indian food, may be enough to prevent and cure the type of pancreatic cancer that afflicted former Apple CEO Steve Jobs, as well as other forms.

The same goes for Nicholas Gonzalez’s claims that he could have saved Jobs.

Round Two

What’s primarily interesting in the new information in this chapter are the details about Jobs’ being listed for liver transplant and how he ended up getting a liver in Tennessee. There has been a lot of speculation that somehow Jobs used his great wealth to “jump the queue” and get a liver more rapidly than he was entitled. As I’ve argued before, he did not, as you will soon see.

One thing I learned that I was right about is that a significant reason for Job’s emaciation in the wake of his surgery was what I had speculated: Complications from his Whipple procedure combined with his obsessive vegan diet. That is, that was the cause before his cancer recurrence. Isaacson described how, even after he had married and had children, he continued to have dubious eating habits. For example, he would spend weeks eating the same thing and then suddenly change his mind and stop eating it. He’d go on fasts. His wife tried to get him to diversify his protein sources and eat more fish, but largely failed. His wife hired a cook who tried to cater to Jobs’ strange eating habits. Indeed, Jobs lost 40 lbs. just during the spring of 2008. Another thing I learned was just how sick Jobs was at this point. His liver metastases had led to excessive secretion of glucagon; he was in a lot of pain and taking narcotics, his liver apparently full of metastases.

It turns out that Jobs was listed for liver transplant in both California and Tennessee, as approximately 3% of transplant recipients manage to list themselves in two different states. Isaacson describes:

There is no legal way for a patient, even one as wealthy as Jobs, to jump the queue, and he didn’t. Recipients are chosen based on their MELD score (Model for End-stage Liver Disease), which uses lab tests of hormone levels to determine how urgently a transplant is needed and on the length of time they have been waiting. Every donation is closely audited, data are available on public websites (optn.transplant.hrsa.gov), and you can monitor your status on the wait list at any time.

Regarding the multiple listing in California and Tennessee:

Such multiple listing is not discouraged by policy, even though critics say it favors the rich, but it is difficult. There were two major requirements: The potential recipient had to be able to get to the chosen hospital within eight hours, which Jobs could do thanks to his plane, and the doctors from that hospital had to evaluate the patient in person before adding him to the list.

Isaacson also reveals that it was a fairly close call. Jobs’ condition was deteriorating rapidly. If he hadn’t been listed in Tennessee, he very likely would have died before a liver became available to him in California. As it was, it wasn’t clear that he wouldn’t die before a liver became available to him in Tennessee. It might seem a bit ghoulish, but it’s the sort of thinking that everyone who’s ever undergone a liver transplant has a hard time avoiding. Isaacson reports that by March 2009 Jobs’ condition was poor and getting worse, but that there was hope among his friends that, because St. Patrick’s Day was coming up and because Memphis was a regional site for March Madness, there was a high likelihood of a spike in automobile crashes due to all the revelry and drinking associated with those events. We even learn that the donor was a young man in his mid-twenties who was killed in a car crash on March 21. It also turns out that Jobs had complications after his surgery. From what I can gather from Isaacson’s account (it wasn’t entirely clear to me) Jobs refused a nasogastric tube when he needed it and as a result aspirated gastric contents when he was sedated, developing a severe postoperative aspiration pneumonia from which at that point “they thought he might die.” Worse, although the transplant was a success, his old liver was riddled with metastases throughout, and surgeons noted “spots on his peritoneum.” Whether these “spots” were metastatic tumor deposits, Isaacson does not say, but it’s a good bet that they probably were.

Assuming Isaacson’s report is accurate and if those “spots” on the peritoneum were indeed metastatic insulinoma, this new information leads me to question more strongly than I did in the past (actually, I didn’t question the decision much at all) whether a liver transplant was a reasonable course of action in Jobs’ case, given that Jobs’ tumor burden in his liver seems to have been much higher than previously reported. If the spots were not cancer, then the transplant, although not contraindicated, was still high risk. In retrospect, it is not surprising that Jobs’ tumor recurred fairly quickly, less than two years after his transplant. Even Isaacson notes that by characterizing Jobs’ transplant as “a success, but not reassuring.” That’s because extrahepatic disease (disease outside of the liver, which peritoneal implants qualify as) is usually an absolute or near-absolute contraindication for liver transplant for cancer, at least in the case of hepatocellular cancer, because the chance of recurrence is so high. I make the analogy to adenocarcinoma of the pancreas, the much more lethal pancreatic cancer that is far more common than the insulinoma that Steve Jobs had. Often, surgeons will perform laparoscopy before attempting a curative resection (the aforementioned Whipple operation). If nodules are noted on the peritoneum, they are biopsied, and if the frozen section comes back as adenocarcinoma, the attempt at curative resection is aborted. The same is true when undertaking a curative resection for liver metastases from colorectal cancer, which can result in long term survival 30-40% of the time, but not if there’s even a hint of a whiff of extrahepatic disease. Although evidence is sketchy for insulinomas, because they’re such rare tumors, it’s hard not to conclude that the same is likely true for them and that extrahepatic disease is a contraindication to liver transplant.

Round Three

This chapter was, as you might imagine, a depressing read. In actuality, there wasn’t much new there or even much in the way of medical details that add much to what we know about Jobs’ course, aside from one revelation that I’ll discuss. First, to begin, in late 2010 Jobs started to feel sick again. Isaacson describes it thusly:

The cancer always sent signals as it reappeared. Jobs had learned that. He would lose his appetite and begin to feel pains throughout his body. His doctors would do tests, detect nothing, and reassure him that he still seemed clear. But he knew better. The cancer had its signaling pathways, and a few months after he felt the signs the doctors would discover that it was indeed no longer in remission.

Another such downturn began in early November 2010. He was in pain, stopped eating, and had to be fed intravenously by a nurse who came to the house. The doctors found no sign of more tumors, and they assumed that this was just another of his perioic cycles of fighting infections and digestive maladies.

In early 2011, doctors detected the recurrence that was causing these symptoms. Ultimately, he developed liver, bone, and other metastases and was in a lot of pain before the end.

The other issue discussed in this final chapter that is of interest to SBM readers is that Jobs was one of the first twenty people in the world to have all the genes of his cancer and his normal DNA sequenced. At the time, it cost $100,000 to do. This sequencing was done by a collaboration consisting of teams at Stanford, Johns Hopkins, and the Broad Institute at MIT. Scientists and oncologists looked at this information and used it to choose various targeted therapies for Jobs throughout the remainder of his life. Whether these targeted therapies actually prolonged Jobs’ life longer than standard chemotherapy would have is unknown, particularly given that Jobs underwent standard chemotherapy as well. It is rather interesting to read the account, however, of how Jobs met with all his doctors and researchers from the three institutions working on the DNA from his cancer at the Four Seasons Hotel in Palo Alto to discuss the genetic signatures found in Jobs’ cancer and how best to target them. Isaacson reports:

By the end of the meeting, Jobs and his team had gone through all of the molecular data, assessed the rationales for each of the potential therapies, and come up with a list of tests to help them better prioritize these.

The results of this meeting were sequential regimens of targeted drug therapies designed to “stay one step ahead of the cancer.” Unfortunately, as is all too often the case, the cancer ultimately caught up and passed anything that even the most cutting edge oncologic medicine could do. It’s always been the problem with targeted therapy; cancers evolve resistance, as Jobs’ cancer ultimately did.

What can we learn?

Even now, nearly four weeks later, there remains considerable discussion of Jobs’ cancer and, in particular, his choices regarding delaying surgery. Just yesterday, a pediatrician named Michele Berman speculating How alternative medicine may have killed Jobs. The article basically consists of many of the same oncologically unsophisticated arguments that I complained about right after Jobs’ death, some of which are included in another blog post on Celebrity Diagnosis. Clearly, an education in lead time bias is required. Does any of this mean that it was a good idea (or even just not a bad idea) for Jobs to have delayed having surgery for nine months? Of course not. Again, surgery was his only hope for long term survival. However, as I’ve pointed out before, chances are that surgery right after his diagnosis probably wouldn’t have saved Jobs, but there was no way to be able to come to that conclusion except in retrospect, and even then the conclusion is uncertain.

Although it’s no doubt counterintuitive to most readers (and obviously to Dr. Berman as well), finding liver metastases at the time of Jobs’ first operation strongly suggests this conclusion because it indicates that those metastases were almost certainly present nine months before. Had he been operated on then, would most likely would have happened is that Jobs’ apparent survival would have been nine months longer but the end result would probably have been the same. None of this absolves the alternative medicine that Jobs tried or suggests that waiting to undergo surgery wasn’t harmful, only that in hindsight we can conclude that it probably didn’t make a difference. At the time of his diagnosis and during the nine months afterward during which he tried woo instead of medicine, it was entirely reasonable to be concerned that the delay was endangering his life, because it might have been. It was impossible to know until later—and, quite frankly, not even then—whether Jobs’ delaying surgery contributed to his death. Even though what I have learned suggests that this delay probably didn’t contribute to Jobs’ death, it might have. Even though I’m more sure than I was before, I can never be 100% sure. Trust me when I say yet again that I really, really wish I could join with the skeptics and doctors proclaiming that “alternative medicine killed Steve Jobs,” but I can’t, at least not based on the facts as I have been able to learn them.

More interesting to me is part of the book where Isaacson reports on what was, in essence, Jobs’ indictment of a flaw in the medical system that he perceived after his second recurrence:

He [Jobs] realized that he was facing the type of problem that he never permitted at Apple. His treatment was fragmented rather than integrated. Each of his myraid maladies was being treated by different specialists—oncologists, pain specialists, nutritionists, hepatologists, and hematologists—but they were not being coordinated in a cohesive approach, the way James Eason had done in Memphis. “One of the big issues in the health care industry is the lack of caseworkers or advocates that are the quarterback of each team,” Powell said.

Isaacson contrasts the fragmented approach to Jobs’ care at Stanford to what is described as a far more integrated approach at Methodist Hospital in Memphis, where Jobs underwent his transplant and where Dr. James Eason was portrayed as having “managed Steve and forced him to do things…that were good for him.” Although it is certainly possible that the difference could be accounted for more by the lack of a person at Stanford with a strong enough personality to tell Jobs what he needed to do and get him to do it, compared to Dr. Eason, who clearly had a personality as strong as Jobs’, the description of fragmented care rings true to me, as I’ve seen this problem myself at various times during my career. One wonders if there is a way to infuse healthcare with some Apple-like integration of care, to build it into the DNA of the system itself as it is built into Apple’s DNA, without having to rely on personalities as strong as Dr. Eason’s apparently was.

Steve Jobs’ eight year battle with his illness is remarkable not so much because he had a rare tumor or because he flirted with alternative medicine for several months before undergoing surgery. Rather, I see Jobs’ case as providing multiple lessons in the complexity of cancer, the difficulty of the decisions that go into cancer care, and how being wealthy or famous can distort those choices. I’ve said it before, but now is as good a time as any to say it again: In cancer, biology is still king. Perhaps one day, when we know how to decode and interpret genomic information of the sort provided when Jobs’ had his tumors sequenced and use that information to target cancers more accurately, we will be able to dethrone that king more than just part of the time and only in certain tumors.

ADDENDUM: Finally, someone seems to agree with me!