The Science-Based Medicine blog was established way back in 2008. Since that time, contributors to this blog have been sounding the alarm about the harmful effects of pseudoscience and conspiracy theories related to health. Few people in positions of authority heeded these warnings or recognized the severity of the threat over the next decade. Sometimes we as health professionals were even mocked for writing about these topics instead of presumably meatier medicine-related topics. The COVID-19 pandemic was the event that brought widespread awareness among physicians, public health officials, and scientists about the harms of medical misinformation, and demonstrated that there is still a lot of interest (and confusion) about rank pseudoscience.

One of the points that David Gorski likes to make is that “everything old is new again” and the pandemic has demonstrated this, again and again. Pseudoscience we thought we had definitively debunked a decade ago keeps finding a new, larger and seemingly even more accepting audience.

I was thinking of Gorski’s adage when I came across Tim Caulfield’s recent piece expressing bewilderment and frustration with his Canadian province’s apparent interest in moving away from a scientific framework for their healthcare system:

At the event, [Alberta Premier Danielle] Smith was also asked whether Alberta would provide funding for homeopathy. Here, her response was more definitive. “I love what you’re saying. Absolutely,” she said. And then she seemed to suggest homeopathy could be part of a strategy to deal with health in a “preventive way” that would stop ailments from becoming acute and, as Smith put it, “then you end up in the hospital.” Soon after this event, Minister of Health Adriana LaGrange mused about the provincial system covering homeopathy, noting that “a lot of Albertans value the services that they get from homeopaths”—homeopathy, despite the government’s enthusiasm, remains a fringe practice in Alberta. And at the federal level, the Conservatives are suggesting weakening the already weak regulation on natural health products, like “supplements and homeopathic medicines.”

Medical history is full of strange practices and beliefs. As scientific principles have become the framework for determining what works (and what doesn’t) work in medicine, we’ve seen progress towards more science-based, evidence-based care. Yet some unscientific practices still exist, despite evidence that they do not work. Homeopathy is one of these practices. While there is no convincing evidence to demonstrate that homeopathic treatments are more effective than a placebo, many consumers and even some health professionals believe homeopathy is an actual health treatment that provides beneficial effects.

Responding to the perceived consumer demand for these products, governments need to make decisions about how to deal with the practice. It could ignore homeopathy, treating it like we might think of astrology: firmly outside of medicine, and for entertainment purposes only. Or it could choose some form of regulation, targeting the providers (homeopaths) or the product (homeopathy), possibly with the goal of managing its use, or perhaps limiting harms to consumers. The risk of regulating nonsense is the perceived legitimacy that recognition and regulation implies. Governments or insurance programs can go even futher than regulation and even pay for these products and services. To understand why this is a very bad idea, it’s necessary to review what homeopathy is, and is not.

Dilutions of Grandeur

Homeopathy is often misunderstood as a natural remedy, akin to a type of herbalism. The marketing and labeling of these “remedies” encourages this perception, often describing homeopathy as a “gentle” and “natural” system of healing. While it is often described as a type of “alternative medicine”, it’s more accurately described as an alternative to medicine, given homeopathic remedies don’t normally contain medicine or active ingredients.

Samuel Hahnemann invented the homeopathy in the early 1800s. Homeopathy is based on the idea that “like cures like”, in that a small dose of what causes a symptom can actually cure that symptom. Like-cures-like is simply magical thinking, a pre-scientific belief that was first described in 1890 by anthropologist Sir James George Frazer in the book The Golden Bough:

If we analyse the principles of thought on which magic is based, they will probably be found to resolve themselves into two: first, that like produces like, or that an effect resembles its cause; and, second, that things which have once been in contact with each other continue to act on each other at a distance after the physical contact has been severed. The former principle may be called the Law of Similarity, the latter the Law of Contact or Contagion.

The so-called “Law of Contagion” is still very much alive, and is the basis for pseudoscientific ideas such as “detox” and “eating clean“. It is also the entire basis of homeopathy.

Proponents of homeopathy believe that any substance can be an effective remedy if it’s sequentially diluted enough: raccoon fur, the fermented duck liver, even pieces of the Berlin Wall are possible remedies. But while they may have different labels, the final products sold are all essentially the same. In the manufacturing process, remedies are diluted in water so dramatically that there’s mathematically almost zero possibility of even a single molecule of the original ingredient remaining. The 30C “potency” is a common dilution used in homeopathy – that’s a dilution of 10-60. If something has been diluted this much, you would have to give two billion doses per second, to six billion people, for 4 billion years, to deliver a single molecule of the original, pre-diluted material. To advocates, this much dilution is a good thing, as it’s to make the “remedy” more potent, not less. These rules contradict core scientific principles as well as what we know about biology and medicine.

When Hahnemann invented homeopathy, he described it as a separate and more effective form of medicine compared to “conventional” medical practices. Given homeopathy is an elaborate placebo system, homeopathy probably was safer than medical practice at the time, which was still based around the idea of the four humors. Eventually, germ theory emerged, ideas of humors disappeared, and medicine slowly turned towards a scientific model based on objective observations. Homeopathy, on the other hand, has never progressed or evolved based on evidence, because it was never based on science or evidence to begin with. Its practices today are frozen in the same beliefs from the 1800s.

Rigorous clinical trials of homeopathy confirm what basic science predicts: homeopathy’s effects are placebo effects. While there are plenty of clinical trials that show homeopathy is associated with positive clinical effects, they are always small, poorly controlled, and often biased. Two comprehensive reviews of the evidence are the 2010 Evidence Check from the United Kingdom’s House of Commons Science and Technology Committee and the 2014 Australian National Health and Medical Research Council review, which reached the following conclusion:

Based on the assessment of the evidence of effectiveness of homeopathy, NHMRC concludes that there are no health conditions for which there is reliable evidence that homeopathy is effective.

Homeopathy should not be used to treat health conditions that are chronic, serious, or could become serious. People who choose homeopathy may put their health at risk if they reject or delay treatments for which there is good evidence for safety and effectiveness. People who are considering whether to use homeopathy should first get advice from a registered health practitioner. Those who use homeopathy should tell their health practitioner and should keep taking any prescribed treatments. The National Health and Medical Research Council expects that the Australian public will be offered treatments and therapies based on the best available evidence.

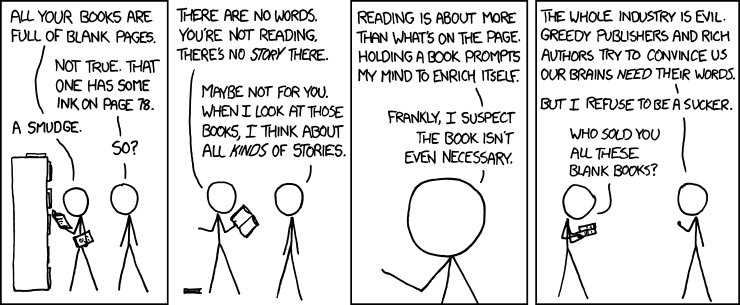

When homeopathic “remedies” are sold commercially, they look like conventional medicine when they’re stocked on pharmacy shelves. The marketing and labeling that is permitted for homeopathic “remedies” in the United States does not draw attention to the lack of active ingredients. Consequently, it would be difficult for the average consumer, who may think of homeopathy as a form of herbalism or natural medicine, to identify that homeopathic remedies are inert. XKCD highlighted the ethical issues with homeopathy in pharmacies several years ago (I have pasted the hover text below):

“I just noticed CVS has started stocking homeopathic pills on the same shelves with–and labeled similarly to–their actual medicine. Telling someone who trusts you that you’re giving them medicine, when you know you’re not, because you want their money, isn’t just lying–it’s like an example you’d make up if you had to illustrate for a child why lying is wrong.”

Real Consequences to Fake Medicine

Using homeopathy in place of real medicine can have fatal consequences. Avoiding actual medicine may be a choice but it can also be a mistake driven by marketing and promotion. Clay Jones noted in a past post how homeopathy contributed to the death of a child:

This case involves the 2017 death of a 7-year-old Italian child whose parents chose to follow recommendations from a local practitioner of homeopathy when their child had an apparent ear infection. Citing their failure to give the child antibiotics, which according to the judge would have prevented the infection from spreading to the brain, the parents were found guilty of aggravated manslaughter and given suspended sentences of three months in prison. The child’s grandfather has defended the convicted couple, stating that they “resorted to homeopathy” only out of concern over the harmful effects of antibiotics and are not anti-medicine in general.

Should Insurance Plans Cover Pseudoscience?

Public health care systems (and governments in general) usually face criticism when they spend money in wasteful ways. With ageing populations and the rising cost of health care there’s more and more scrutiny of what health insurance programs like Medicare and Medicaid play for. Services like homeopathy are not typically paid for by public health insurance because of their lack of evidence.

When public insurance doesn’t pay, private insurance may step in. And private insurance programs, from my observation, tend to be less evidence-based than public programs. They’re often offered as a benefit to employees, and so the occasional massage may be seen as a nice perk, even though it may not be medically necessary.

Australia has a comprehensive public healthcare system which is supplemented by private insurance to cover the cost of treatments and service that are not publicly funded. In 2015 the Australian government completed a review of “natural” treatments, including homeopathy, which were covered by private plans to determine if these therapies were effective, safe, and provided good value for money. While you might wonder why a government would care about what private insurance covers, it’s because the Australian government offers a rebate on insurance premiums, effectively subsidizing their cost.

With respect to homeopathy, the authors of the review looked at the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council report as part of this review. They noted that there is little high-quality evidence, the available evidence is not compelling, and overall fails to demonstrate that homeopathy is an effective treatment for any condition. Subsequently, the Australian government has removed coverage for all 17 therapies studied in the initial review, including homeopathy. What this meant was that while people can still choose to access these therapies, they cannot be offered as benefits under these (subsidized) private insurance programs.

Homeopathy is ineffective

I have written about homeopathy more time that I would like – it’s probably my most frequent topic. Since I started practicing pharmacy I have seen it move from a very fringe product to one that is easy to find in every pharmacy. To be clear, what people want to do with their own money and with full understanding of the facts is entirely their decision. If you’ve never bought it before, homeopathy is not cheap: Its prices are comparable to conventional products that actually have medicine in it. Given the lack of efficacy however, every dollar spent on homeopathy – particularly by insurance programs – is a waste of resources, in that it could otherwise be put to more effective use — for plausible treatments, or anything else, for that matter.