Well, actually it both amuses me and appalls me. The amusement comes from just how utterly ridiculous the concepts behind homeopathy are. Think about it. It is nothing but pure magical thinking. Indeed, at the very core of homeopathy is a concept that can only be considered to be magic. In homeopathy, the main principles are that “like heals like” and that dilution increases potency. Thus, in homeopathy, to cure an illness, you pick something that causes symptoms similar to those of that illness and then dilute it from 20C to 30C, where each “C” represents a 1:100 dilution. Given that such levels of dilution exceed Avagaddro’s number by many orders of magnitude, even if any sort of active medicine was used, there is no active ingredient left after a series of homeopathic dilutions. Indeed, this was known as far back as the mid-1800’s. Of course, this doesn’t stop homeopaths, who argue that water somehow retains the “essence” of whatever homeopathic remedy it has been in contact with, and that’s how homeopathy “works.” Add to that the mystical need to “succuss” (vigorously shake) the homeopathic remedy at each dilution (I’ve been told by homeopaths, with all seriousness, that if each dilution isn’t properly succussed then the homeopathic remedy will not attain its potency), and it’s magic all the way down, just as creationism has been described as “turtles all the way down.” Even more amusing are the contortions of science and logic that are used by otherwise intelligent people to make arguments for homeopathy. For example, just read some of Lionel Milgrom‘s inappropriate invocations of quantum theory at the macroscopic level for some of the most amazing woo you’ve ever seen, or Rustum Roy‘s claims for the “memory of water.” Indeed, if you want to find out just how scientifically bankrupt everything about homepathy is, my co-blogger Dr. Kimball Atwood started his tenure on Science-Based Medicine with a five part series on homeopathy.

At the same time, homeopathy appalls me. There are many reasons for this, not the least of which is how anyone claiming to have a rational or scientific viewpoint can fall so far as to twist science brutally to justify magic. Worse, homepaths and physicians sucked into belief into the sorcery that his homeopathy are driven by their belief to carry out unethical clinical trials in Third World countries, even on children. Meanwhile, time, resources, and precious cash are wasted chasing after pixie dust by our own government through the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM). So while I laugh at the antics of homeopaths going on and on about the “memory of water” or quantum gyroscopic models” in order to justify homeopathy as anything more than an elaborate placebo, I’m crying a little inside as I watch.

The Lancet, meta-analysis, and homeopathy

If there’s one thing that homepaths hate–I mean really, really, really hate–it’s a meta-analysis of high quality homeopathy trials published by Professor Matthias Egger in the Department of Social and Preventative Medicine at the University of Berne in Switzerland, entitled Are the clinical effects of homoeopathy placebo effects? Comparative study of placebo-controlled trials of homoeopathy and allopathy.

What Shang et al did in this study was very simple and very obvious. They applied the methods of meta-analysis to trials of homeopathy and allopathy. (I really hate that they used the term “allopathy” to distinguish scientific medicine from homeopathy, although I can understand why they might have chosen to do that for simple convenience’s sake. Still, it grates.) In any case, they did a comprehensive literature search for placebo-controlled trials of homeopathy and then randomly selected trials of allopathy matched for disorder and therapeutic outcome. Criteria used for both were controlled trials with a randomized parallel design and a placebo control with sufficient data presented in the published report to allow the calculation of an odds ratio. These studies were assessed for quality using measures of internal validity, including: randomization, blinding or masking, and data analysis by intention to treat or other. Standard measures of how good the randomization and blinding techniques used in each study are. To boil down the results, the lower the quality of the trial and the smaller the numbers, the more likely a trial of homeopathy was to report an odds ratio less than one (the lower the number the more “positive”–i.e., therapeutic–the effect). The higher the quality of the study and the greater the number of subjects, the closer to 1.0 its odds ratio tended to be. The same was true for trials of allopathy as well, not surprisingly. However, analysis of the highest quality trials showed a range of odds ratios with a 95% confidence interval that overlapped 1.0, which means that there was no statistically significant difference between them and 1.0; i.e., there was not detectable effect. For the very highest quality trials of allopathy, however, there was still an odds ratio less than 1.0 whose confidence level did not include 1.0. The authors concluded:

We acknowledge that to prove a negative is impossible, but we have shown that the effects seen in placebocontrolled trials of homoeopathy are compatible with the placebo hypothesis. By contrast, with identical methods, we found that the benefits of conventional medicine are unlikely to be explained by unspecific effects.

The problems with meta-analysis notwithstanding, as an exercise in literature analysis, Shang et al was a beautiful demonstration that whatever effects due to homeopathy “detected” in clinical trials are nonspecific and not detectably different from placebo effects, exactly as one would anticipate based on the basic science showing that homeopathy cannot work unless huge swaths of our current understanding of physics and chemistry are seriously in error. After all, homeopathic dilutions greater than 12C or so are indistinguishable from water. It’s thus not surprising that homeopaths have been attacking Shang et al beginning the moment it was first published. Indeed, they’ve attacked Dr. Egger as biased and even tried to twist the results to claiming that homepathy research is higher quality than allopathy research. Shang et al may not be perfect, but it’s pretty compelling evidence strongly suggesting that homeopathy is no better than placebo, and the interpretation that, just because more of homeopathy studies identified in the study were of higher quality does not mean that homeopathic research is in general of higher quality than scientific medical research.

Shang et al “blown out of the water”?

Recently, a certain well-known homeopath who’s appeared not only on this blog to defend homeopathy but on numerous blogs has reappeared. His name is Dana Ullman, and he’s recently reappeared on this blog to comment in a post that is several months old and happens to be about homeopathy trials in Third World countries. Indeed, I sometimes think that periodically Mr. Ullman gets bored and decides to start doing blog searches on homeopathy, the better to harass bloggers who criticize his favored form of pseudoscience. No doubt he will appear here as a result of this post, mainly because he’s lately been crowing about another study that he believes to show that Shang et al has been “blown out of the water,” as he puts it.

That’s actually a rather funny metaphor coming from a homeopath, given that homeopathy is nothing more than water. Suffice it to say that our poor overwrought Mr. Ullman is becoming a bit overheated, as is his wont. The guy could really use some propranolol to settle his heartrate down a bit. In any case, the study to which he refers, entitled The conclusions on the effectiveness of homeopathy highly depend on the set of analyzed trials and coming from a clearly pro-homeopathy source, Dr. Rutten of the Association of Dutch Homeopathic Physicians, it’s hot off the presses (the electronic presses, that is, given that this is an E-pub ahead of print) in the October issue of the Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. Suffice it to say that, as always, Mr. Ullman is reading far more into the study than it, in fact, actually says.

The first thing that anyone who’s ever read or done a meta-analysis will already know is that the title of this study by Lüdtke and Rutten is about as close to a “Well, duh!” title as there is. Of course, the conclusions of a meta-analysis depend on the choice of trials used for the analyzed set. That’s exactly the reason why the criteria for choosing trials to include in a meta-analysis are so important and need to be stringently decided upon prospectively, before the study is done. If they aren’t, then investigators can cherry pick studies as they see fit.. That’s also exactly why the critieria need to be designed to include the highest quality studies possible. In fact, I’d be shocked if a reanalysis of a meta-analysis didn’t conclude that the results are influenced by the choice of studies. That being said, the results of Lüdtke and Rutten do not in any way invalidate Shang et al.

One thing that’s very clear reading Lüdtke and Rutten is that this study was clearly done to try to refute or invalidate Shang et al. It’s so obvious. Indeed, no one reanalyzes the data from a study unless they think the original conclusions from it were wrong. No one. There’s no motivation otherwise. Otherwise, why bother to go through all the work necessary? Indeed, Lüdtke and Rutten show this right from the beginning:

Shang’s analysis has been criticized to be prone to selection bias, especially when the set of 21 high quality trials was reduced to those eight trials with large patient numbers. In a letter to the Lancet, Fisher et al. posed the question: ‘‘to what extend the meta-analysis results depend on how the threshold for ‘large’ studies was defined [3]. The present article addresses this question. We aim to investigate how Shang’s results would have changed if other thresholds had been applied. Moreover, we extend our analyses to other meaningful subsets of the 21 high quality trials to investigate other sources of heterogeneity, an approach that is generally recommended to be a valuable tool for meta-analyses.

Again, this is a “Well, duh!” observation, but it’s interesting to see what Lüdtke and Rutten did with their analysis, because it more or less reinforces Shang et al‘s conclusions, even though Lüdtke and Rutten try very hard not to admit it. What Lüdtke and Rutten did was to take the 21 high quality homeopathy studies analyzed by Shang et al. First off, they took the odds ratios from the studies and did a funnel plot of odds ratio versus standard error, which is, of course, dependent on trial size. The funnel plot showed an assymetry, which was mainly due to three trials, two of which showed high treatment effects and one of which was more consistent with placebo effect. In any case, however, for the eight highest quality trials, no assymetry was found.

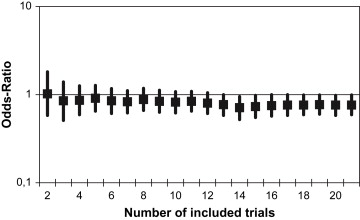

What will likely be harped on by homeopaths is that for all 21 of the “high quality” homeopathy trials, the pooled odds ratio from random effect meta-analysis was 0.76 (confidence interval 0.59-0.99. p=0.039). This is completely underwhelming, of course. Even if real, it would likely represent a clinically irrelevant result. What makes me think it’s not clinically relevant is what Lüdtke and Rutten do next. Specifically, they start with the two largest high quality studies of homeopathy and then serially add studies, from those with the highest numbers of patients to those with the lowest. At each stage they calculated the pooled odds ratio. At two studies, the odds ratio remained at very close to 1.0. After 14 trials, the odds ratio became and remained “significantly” less than 1.0 (except when 17 studies were added). The graph:

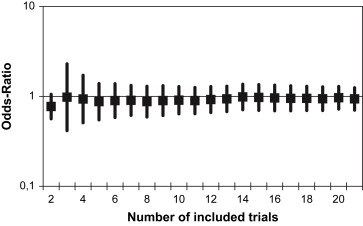

However, when the authors used meta-regression, a different form of analysis, it didn’t matter how many studies were included. The confidence interval always spanned 1.0, meaning a result indistinguishable statistically from an odds ratio of 1.0:

In other words, if a random effect meta-analysis is used, one can torture marginally significant odds ratios out of the data; if a meta-regression is used, one can’t even manage that! In other words, this study actually shows tht it doesn’t really matter too much which high quality studies are involved, other than that adding lower quality studies to higher quality studies starts to skew the results to seemingly positive values.

Exactly as one who knows anything about meta-analysis would predict.

The amazing thing about Lüdtke and Rutten’s study, though, is just how much handwaving is involved to try to make this result sound like a near-refutation of Shang et al. For example, they start their discussion out thusly:

In our study, we performed a large number of meta-analyses and meta-regressions in 21 high quality trials comparing homeopathic medicines with placebo. In general, the overall ORs did not vary substantially according to which subset was analyzed, but P-values did.

That is, in essence, what was found, and the entire discussion is nothing more than an attempt to handwave, obfuscate, and try to convince readers that there is some problem with Shang et al that render its conclusions much less convincing than they in fact are. Indeed, I fear very much for them. They’ll get carpal tunnel syndrome with all that handwaving. We’re talking cherry picking subset analysis until they can find a subset that shows an “effect.” More amusingly, though, even after doing all of that, this is the best they can come up with:

Our results do neither prove that homeopathic medicines are superior to placebo nor do they prove the opposite. This, of course, was never our intention, this article was only about how the overall resultsdand the conclusions drawn from themdchange depending on which subset of homeopathic trials is analyzed. As heterogeneity between trials makes the results of a meta-analysis less reliable, it occurs that Shang’s conclusions are not so definite as they have been reported and discussed.

I find this particularly amusing, given that Shang et al bent over backwards not to oversell their results or to make more of them than they show. For example, this is what they said about their results:

We emphasise that our study, and the trials we examined, exclusively addressed the narrow question of whether homoeopathic remedies have specific effects. Context effects can influence the effects of interventions, and the relationship between patient and carer might be an important pathway mediating such effects.28,29 Practitioners of homoeopathy can form powerful alliances with their patients, because patients and carers commonly share strong beliefs about the treatment’s effectiveness, and other cultural beliefs, which might be both empowering and restorative.30 For some people, therefore, homoeopathy could be another tool that complements conventional medicine, whereas others might see it as purposeful and antiscientific deception of patients, which has no place in modern health care. Clearly, rather than doing further placebo-controlled trials of homoeopathy, future research efforts should focus on the nature of context effects and on the place of homoeopathy in health-care systems.

This is nothing more than a long way of saying that homeopathy is a placebo. However, all the qualifications, discussions of “alliances with patients, and reference to cultural beliefs represent an excellent way to say that homeopathy is a placebo nicely rather than in the combative way that I (not to mention Dr. Atwood) like to affect. One thing I can say for sure, though, is that whatever it is that Lüdtke and Rutten conclude in their study (and, quite frankly, as I read their paper I couldn’t help but think at many points that it’s not always entirely clear just what the heck they are trying to show), it is not that Shang et al is invalid, nor is it evidence that homeopathy works.

Indeed, the very title is misleading in that what the study really does is nothing more than to reinforce the results of Shang et al, looking at them in a different way. Indeed, the whole conclusion of Lüdtke and Rutten seems to be that Shang et al isn’t as hot as everyone thinks, except that they exaggerate how hot everyone thought Shang et al was in order to make that point. That’s about all they could do, after all, as they were about as successful at shooting down Shang et al through reanalysis of the original data as DeSoto and Hitlan were when they “reanalyzed” the dataset used by Ip et al to show no correlation between the presence of autism and elevated hair and blood mercury levels and then got in a bit of a blog fight over it. Again, whenever one investigator “reanalyzes” the dataset of another investigator, they virtually always have an axe to grind. That doesn’t mean it isn’t worthwhile for them to do such reanalyses or that they won’t find serious deficiencies from time to time, but you should always remember that the investigators doing the reanalysis wouldn’t bother to do it if they didn’t disagree with the conclusions and weren’t looking for chinks in the armor to blast open so that they can prove the study’s conclusions wrong. In this, Lüdtke and Rutten failed.

The inadvertent usefulness of homeopathy trials to science-based medicine

Viewing the big picture, I suppose I can say that there is one useful function that trials of homeopathy serve, and that is to illuminate the deficiencies of evidence-based medicine and how our clinical trial system works. Again, the reason is that homeopathy is nothing more than water and thus an entirely inert placebo treatment. Consequently, any positive effects reported for or any positive correlations attributed to homeopathy must be the result of chance, bias, or fraud. Personally, I’m an optimist and as such tend to believe that fraud is uncommon, which leaves chance or bias. Given the known publication bias in which positive studies are more likely to be published and, if published, more likely to be published in better journals, I feel quite safe in attributing the vast majority of “positive” homeopathy trials either to bias or random chance. After all, under the best circumstances, at least 5% of even the best designed clinical trials of a placebo like homeopathy will be seemingly “positive” by random chance alone. But it’s worse than that Dr. John Ioannidis’ groundbreaking research tells us is that the number of false positive trials is considerably higher than 5%. Indeed, lower the prior probability that a trial will show a positive result, the greater the odds of a false positive trial become. That’s the real significance of Ioannidis’ work. Indeed, a commenter on Hawk/Handsaw put described very well how homeopathy studies illuminate the weaknesses of clinical trial design, only not in the way that homeopaths tell us:

…I see all the homeopathy trials as making up a kind of “model organism” for studying the way science and scientific publishing works. Given that homeopathic remedies are known to be completely inert, any positive conclusions or even suggestions of positive conclusions that homeopathy researchers come up with must be either chance findings, mistakes, or fraud.

So homeopathy lets us look at how a community of researchers can generate a body of published papers and even meta-analyze and re-meta-analyze them in great detail, in the absence of any actual phenomenon at all. It’s a bit like growing bacteria in a petri dish in which you know there is nothing but agar.

The rather sad conclusion I’ve come to is that it’s very easy for intelligent, thoughtful scientists to see signals in random noise. I fear that an awful lot of published work in sensible fields of medicine and biology is probably just that as well. Homeopathy proves that it can happen. (the problem is that we don’t know what’s nonsense and what’s not within any given field.) It’s a warning to scientists everywhere.

Indeed it is, and it applies to meta-analysis just as much as any study, given that meta-analysis pools such stucies. It’s also one more reason why we here at Science-Based Medicine emphasize science rather than just evidence. Moreover, failure to take into account prior probability based on science is exactly what we find lacking in the current paradigm of evidence-based medicine. We do not just include trials of “complementary and alternative medicine” (CAM) in this critique, either. However, trials of homeopathy are about as perfect an example as we can imagine to drive home just how easy it is to produce false positives in clinical trials when empiric evidence is valued more than the totality of scientific evidence. There may be other examples of CAM modalities that have specific effects above and beyond that of a placebo (herbal remedies for example, given that they are drugs). There may be. But to an incredibly high degree of certainty, homeopathy is not among them. Homeopathic remedies are, after all, nothing but water, and their efficacy only exists in the minds of homeopaths, who are, whether they realize it or not, masters of magical thinking, or users of homeopathy, who are experiencing the placebo effect first hand. Studies of homeopathy demonstrate why, in the evidence-based medicine paradigm, there will always be seemingly positive studies to which homeopaths can point, even though homeopathic remedies are water.

REFERENCES:

1. A SHANG, K HUWILERMUNTENER, L NARTEY, P JUNI, S DORIG, J STERNE, D PEWSNER, M EGGER (2005). Are the clinical effects of homoeopathy placebo effects? Comparative study of placebo-controlled trials of homoeopathy and allopathy The Lancet, 366 (9487), 726-732 DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67177-2

2. R LUDTKE, A RUTTEN (2008). The conclusions on the effectiveness of homeopathy highly depend on the set of analyzed trials Journal of Clinical Epidemiology DOI: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2008.06.015