Since we hit the 15-year anniversary of this blog, I’ve been thinking more about the overall concept of science-based medicine (SBM) as compared to the evidence-based medicine (EBM) paradigm than I probably have since Steve Novella first invited me to join this blog’s founders in 2007 as he was planning on launching the blog. I remember some epic email exchanges that took place during the weeks leading up to the blog’s launch on January 1, 2008. It is in this light that I will address a proposal made on Friday by Dr. Vinay Prasad and explain why I think it’s a very bad idea—not just a bad idea but a nice jumping-off point to address how EBM fundamentalism has contributed to two major problems in medicine, that of the “integration” of quackery as though it were medicine and COVID-19 minimization and even outright antivaccine attacks on COVID-19 vaccines. The title will likely be a tip-off: Rethinking Medical Education: Evidence First, Biology Later. In the post, Dr. Prasad proposes “placing evidence-based medicine at the fore, right from the get-go,” by teaching EBM first and basic biological sciences after that.

[ADDENDUM: Dr. Prasad now says that his essay was written using Chat GPT. Comments at the end of the post. Let’s just say that it’s not the flex that he thinks it is.]

While one can look at this proposal as just another iteration in the eternal debate over the relative roles of basic and clinical science education in medical school, I look at it a bit differently. Specifically, I look at it through the lens of the criticisms that we at SBM have been making about EBM since the very beginning and, more recently, have been expanding to cover observations that I’ve noticed regarding the tendency of prominent EBM advocates (e.g., John Ioannidis) to embrace questionable ideas about COVID-19 and public health.

SBM vs. EBM

To set the stage, let me briefly quote from Steve Novella’s inaugural post announcing the blog, after which I will begin addressing the problems with Dr. Prasad’s idea and how it fits into the problem with EBM that we at SBM have been pointing out for over 15 years:

Within the practice of medicine there is already a recognition of the need to raise the standards of evidence and the availability of the best evidence to the practitioner and the consumer – formalized in the movement known as evidence-based medicine (EBM). EBM is a vital and positive influence on the practice of medicine, but it has its limitations. Most relevant to this blog is the focus on clinical trial results to the exclusion of scientific plausibility. The focus on trial results (which, in the EBM lexicon, is what is meant by “evidence”) has its utility, but fails to properly deal with medical modalities that lie outside the scientific paradigm, or for which the scientific plausibility ranges from very little to nonexistent.

All of science describes the same reality, and therefore it must (if it is functioning properly) all be mutually compatible. Collectively, science builds one cumulative model of the natural world. This means we can make rational judgments about what is likely to be true based upon what is already well established. This does not necessarily equate to rejecting new ideas out-of-hand, but rather to adjusting the threshold of evidence required to establish a new claim based upon the prior scientific plausibility of the new claim. Failure to do so leads to conclusions and recommendations that are not reliable, and therefore medical practices that are not reliably safe and effective.

This is why the authors of this blog strongly advocate for science-based medicine – the use of the best scientific evidence available, in the light of our cumulative scientific knowledge from all relevant disciplines, in evaluating health claims, practices, and products.

Let me start out by pointing out a commonality that we share with Dr. Prasad, for all our past criticism, which is that the standard of evidence in medicine does need to be raised. Indeed, before the pandemic I once argued that the FDA is too lax in its standards for drug and device approval, rather than too strict, as many libertarians who want to weaken the FDA like to argue. Where we differ is that, while SBM argues for the use of all the best scientific evidence available from all disciplines, Dr. Prasad, like many of what I have come to call “EBM fundamentalists” thinks that the EBM paradigm is the only form of evidence that matters, a phenomenon that I have long been calling “methodolatry,” a term that I discovered in 2009 thanks to a senior epidemiologist and defined as the profane worship of the randomized controlled trial as the only valid form of clinical investigation. Moreover, my discovery of methodolatry was in the context of an earlier pandemic, namely the H1N1 influenza pandemic of 2009-2010 and how EBM fundamentalists did something very similar to what they have been doing during the current COVID-19 pandemic, demanding RCTs for public health interventions for which RCTs are either impractical, too slow, or even unethical.

In 2007, the main concern that had led to the proposal of SBM was the rise of what was then commonly called “complementary and alternative medicine” (CAM) but has since been consciously rebranded by its proponents as “integrative medicine” or “integrative health” in order to remove the word “alternative” (which has a bad connotation) and “complementary” (which implies a lower status than EBM). The basic idea behind integrative medicine is to “integrate” what advocates sometimes call the “best of both worlds”; i.e., to “integrate” various alternative medicine modalities into conventional evidence-based medicine.

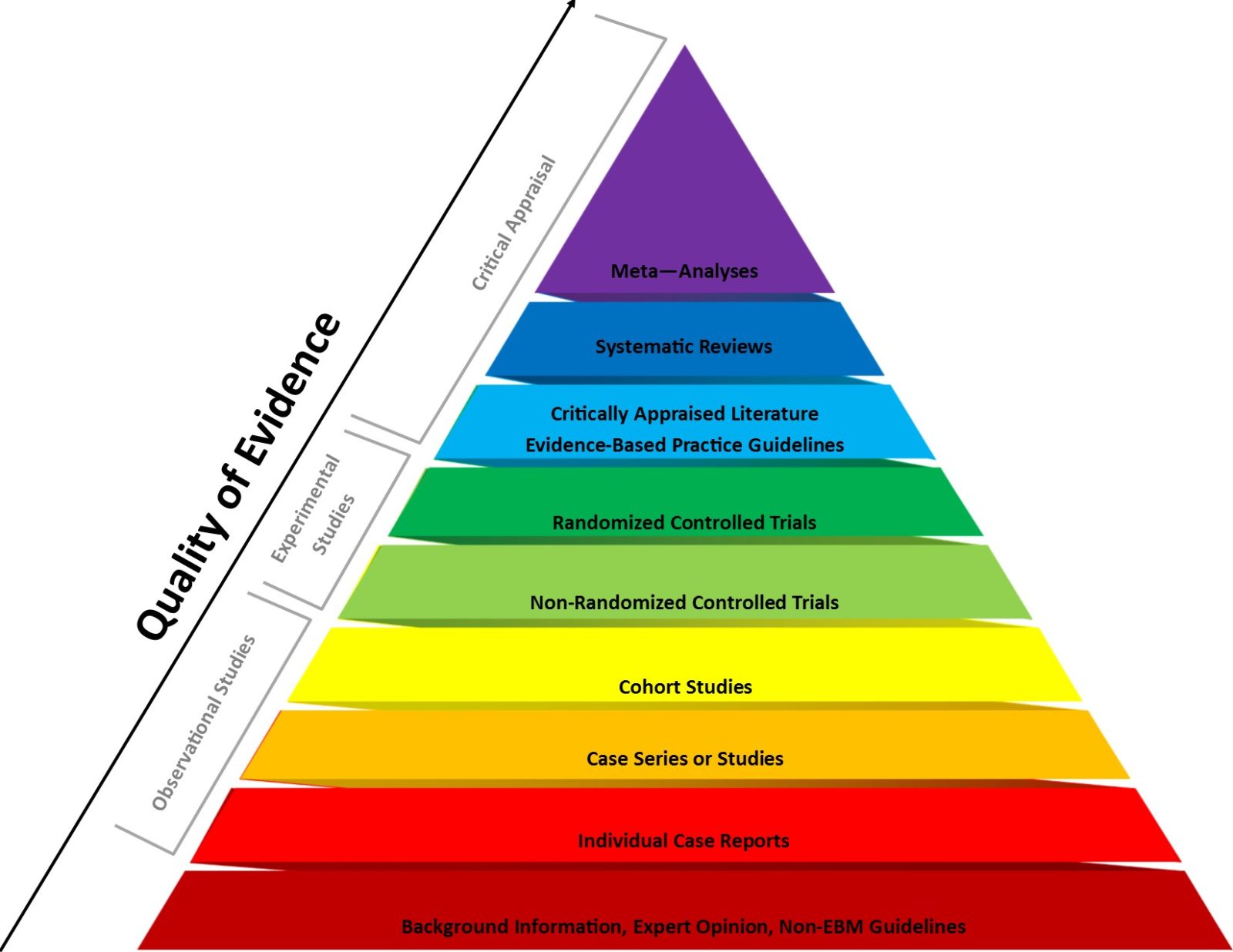

Believe it or not, at the time I wasn’t entirely on-board with the whole concept of SBM and had to be convinced, hence the epic email exchanges. (This was 2007.) The reason was that I could not accept the central premise of SBM, specifically that the EBM paradigm hugely undervalues basic science considerations in considering the evidence for various highly implausible treatments being “integrated” into medicine and that Bayesian prior plausibility should be introduced into EBM to correct that “blind spot.” If you look at the EBM pyramid, you will see that basic science is near the bottom, while RCTs and meta-analyses of RCTs are at the very top.

Let’s just say that I had to be convinced of SBM’s central premise, and it took a lot of convincing to accept that my view of EBM at the time was hopelessly naive in just assuming that surely, EBM pyramid aside, basic science must be a major consideration and that RCTs of “impossible” treatments like homeopathy should not be done.We used to routinely note that basic science considerations are relegated to the very bottom of the pyramid, as “level 5 evidence” consisting of “expert opinion without explicit critical appraisal, or based on physiology, bench research or ‘first principles.'”” This is a model that fails when it comes to addressing alternative medicine treatment modalities that hundreds of years of chemistry, physics, and biology show to be impossible from a basic science standpoint, our favorite example being homeopathy.

Given that I recently discussed this concept in detail, I won’t rehash it (much). Instead I will point to a classic SBM post by Dr. Kimball Atwood asking: Does EBM Undervalue Basic Science and Overvalue RCTs? (Hint: the answer is yes.) He also wondered whether it is a good idea to test highly implausible health claims. (Hint: the answer is usually no, at least not using RCT efficacy trials of the sort placed near the very top of the EBM pyramid of evidence, just under systemic reviews, evidence syntheses, and meta-analyses of RCTs.)

As I like to ask: Which of the following is more likely, that a 30C homeopathic solution of…something…that has been diluted on the order of 1037-fold more than Avogadro’s number and thus is incredibly unlikely to contain even a single molecule of that something has a therapeutic effect or that the RCTs concluding that it does reveal the problems and biases in clinical trials? As I also like to say, given the usual p-value of 0.05 designated for “statistically significant” findings, under ideal circumstances, with perfectly designed and executed RCTs, by random chance alone 5% of these RCTs will be “positive.” Of course, in the real world, RCTs are not perfect, either in design or execution, and the number of “false positives” is therefore likely considerably higher than 5%. Yet, basic science alone tells us that a 30C homeopathic remedy is indistinguishable from the water used to dilute it, which means a placebo-controlled RCT is testing placebo versus placebo and “positive” results show us nothing more than the noise inherent in doing RCTs.

Now, as I did then, I will also add this caution: EBM is correct that “first principles” in basic science cannot tell you whether a treatment works or not—except for scientifically impossible treatment modalities like homeopathy, that is. Aside from testing treatments that violate multiple well-established laws of physics, RCTs are indeed necessary to determine if a treatment is safe and effective. It is also true that history is littered with treatments that appeared effective in preclinical in vitro and animal models but failed to pan out in clinical trials, a point that Dr. Prasad alludes to, as you will see, but using an argument that can backfire. However, in contrast, if very well-established basic science tells you that a treatment modality is impossible and cannot work, that (like homeopathy) and would require that multiple well-established laws and theories of chemistry and physics be not just wrong, but spectacularly wrong, in order for it to “work,” then that should be enough. RCTs should not be necessary. Indeed, they would arguably be unethical, because one of the major ethical requirements for clinical trials is that the treatment being tested be grounded in good science based on what is known at the time of the trial, and clinical trials of many alternative medicine modalities (e.g., homeopathy, reflexology, reiki, and more) violate this precept.

Contrary to straw man attacks against SBM, we only ever intended the idea of considering prior plausibility as a way of ruling out impossible treatments like homeopathy without RCTs, which inevitably produce false positives that advocates of quackery like to cite, and to put RCTs of highly implausible but not necessarily totally impossible treatments (e.g., acupuncture) into context by assessing how likely it is that a positive RCT represents a “true positive.” (Hint: very unlikely.) As we have long argued, medicine does need more science, but unlike what EBM fundamentalists seem to believe, RCTs are not the be-all and end-all of clinical science, particularly for nonpharmaceutical and non-device interventions used in public health, for which RCTs are not infrequently incredibly impractical, expensive, or even—in the middle of a pandemic, for instance—unethical.

So what does this have to do with Dr. Prasad’s proposal?

EBM (and RCTs) über alles

Let’s now see what, exactly, it is that Dr. Prasad proposes and how he justifies it:

Medical education has got it backward. We’re front-loading biology and anatomy, then backfilling with the principles of evidence-based medicine. We need to flip this equation, placing evidence-based medicine at the fore, right from the get-go. Patients don’t care about the biological mechanisms; they care about what helps them get better, regardless of the underlying science. That’s the crux of our argument today.

Let’s take a step back and look at the evolution of medical education over the 20th century. With the boom in biological sciences, our understanding of human anatomy, physiology, and pathology has expanded exponentially. This knowledge has undoubtedly been invaluable, forming the bedrock of our modern approach to diagnosing and treating diseases. There’s a problem, though. By placing biology at the center of medical education, we’ve inadvertently created a situation where we’re missing the forest for the trees.

“Patients don’t care about medical mechanisms, they care about what helps them get better, regardless of the underlying science”? Andrew Weil or David Katz couldn’t have said it better himself. That statement definitely sent up a huge red flag! After all, how many times have critics of SBM said something very similar over the years? In fairness, it is true that patients don’t care so much about the basic science compared to the efficacy and safety of a treatment, but in determining which treatments are likely to work basic science does and should have a major role. We physicians are not patients. We do have to care about basic science. Some of us—such as myself—are even also basic or translational scientists. We’ve been arguing for well over a century, ever since the Flexner report, over how much basic science we as physicians need to know, but the answer has always been that basic science is as important as clinical knowledge in medical education.

Let’s get to the part of Dr. Prasad’s argument that made my jaw drop:

Simultaneously, another revolution was brewing in the medical field during the 20th century: the rise of evidence-based medicine. Randomized clinical trials (RCTs) became the gold standard, the north star guiding our therapeutic decisions. The power of RCTs lies in their objectivity, their ability to tell us, unequivocally, whether an intervention works or not. It’s not about hypotheses or educated guesses; it’s about cold, hard data. Yet, this pillar of modern medicine often plays second fiddle in our educational curriculum.

Here’s the rub: when we instill a deep-seated reverence for biology before introducing the principles of evidence-based medicine, we’re setting up our future doctors for cognitive dissonance. It’s harder to accept that a treatment doesn’t work when it “should” according to biological principles. As a result, evidence that contradicts our understanding of biology is often met with skepticism, even outright rejection. This is a disservice to our patients, who ultimately care about outcomes, not biological plausibility.

This is EBM fundamentalism at its most blatant. Notice how Dr. Prasad equates EBM with RCTs. He doesn’t mention anything else, including epidemiology, which, if you look again at the EBM pyramid above, you will notice to be under RCTs—under nonrandomized clinical trials, actually. When I refer to “methodolatry,” this is exactly what I’m talking about, the assumption, sometimes stated but often unstated, that the RCT is the only valid method of clinical investigation that can produce a definitive answer to a question. My favorite counterexamples to this are both from epidemiology. The first is how it is by epidemiology alone that we discovered that smoking causes lung cancer—and so many other diseases. The second is how it is primarily though epidemiology (along with a few RCTs, admittedly) that we know that vaccines are not associated with an increased risk of autism. It would be completely unethical (and probably impossible) to attempt RCTs addressing the questions of whether smoking causes cancer and vaccines cause autism now. In a more balanced paradigm, we in medicine would use the right scientific tools to address the correct question. RCTs are undoubtedly the right scientific tools for the initial testing of whether a new drug, surgical procedure, or medical device is safe and effective for its intended purpose. After that, it gets more…complicated, particularly when ethical considerations of clinical equipoise start entering into the equation.

Also, RCTs are “objective”? Yes, but only in comparison to other methods and only along a continuum of objectivity. Like any other scientific tool, no RCT is truly completely objective; the idea is to approach objectivity, to minimize bias as much as is feasible and ethical. At their best, RCTs can and do tell us unequivocally whether an intervention works or not and are generally the least bias-prone method of doing so. In an ideal world, they would all accomplish that. However, Dr. Prasad himself before the pandemic routinely used to demonstrate how they often do not. It turns out that RCTs are messier than this idealized version portrayed by Dr. Prasad would indicate. We’ve even discussed this at SBM and elsewhere not just in terms of RCTs of “integrative” medicine interventions but of just…interventions. At times, we’ve even praised Dr. Prasad for his previous work. Unfortunately that was in 2017, and it’s 2023 now. Dr. Prasad has changed.

The “rub” that Dr. Prasad cites is also a red flag. In essence, he is arguing against the very concept of SBM in that he seems to view considering scientific prior plausibility to be a bad thing. Acupuncturists and homeopaths couldn’t have said it better! Let me just flip Dr. Prasad’s assertion that it is “harder to accept that a treatment doesn’t work when it ‘should’ according to biological principles” on its head to show you what I mean: It is easier to dismiss scientific considerations that assess the prior plausibility of an intervention, the prior probability that it will work, as very low or even impossible if basic science considerations don’t matter. In addition, how, precisely, do we decide which clinical interventions to test in Dr. Prasad’s vaunted RCTs if we don’t have some basis upon which to assess the likelihood that they will work? His version of EBM appears to reject completely the current drug and device development paradigm, which starts with basic science interventions, moves to testing the interventions in cell culture and animal models, and then to small scale pilot clinical trials, and finally to the large RCTs that Dr. Prasad presents as the best method to test clinical interventions. Under a paradigm like the one described above, one could justify testing almost anything just on the basis of anecdotal evidence, which is the lowest form of evidence in clinical medicine, including homeopathy. After all, patients (and apparently Dr. Prasad) don’t care about basic science, just efficacy and safety, so why not?

Don’t believe me? Dr. Prasad states it outright near the end:

This brings us to the crux of our argument: the need to revamp the medical curriculum. Let’s start with the history of medicine, the triumphs, and the pitfalls. Next, introduce the principles of clinical trials, the linchpin of evidence-based medicine. Show students examples of medical reversals, such as the Cardiac Arrhythmia Suppression Trial (CAST), where our understanding of biology was turned on its head by clinical trial data. Such an approach will underscore the importance of evidence over theory, preparing our future doctors to prioritize patient outcomes over biological dogma.

First, beware of anyone who uses phrases like “biological dogma.” I can’t count the number of times I’ve seen, for example, homeopaths use this or similar terminology to dismiss basic science considerations that show that homeopathy is scientifically impossible. In fairness, I will also state that it would not be a bad idea to teach a lot more about the history of medicine, in particular of ideas widely accepted that turned out to be wrong, but one does have to remember that there is only a limited amount of time. Adding topics to the curriculum nearly always results in deemphasizing or eliminating other topics. Which topics would Dr. Prasad deemphasize or eliminate?

It is, of course, true that the CAST trial did produce a result in conflict with the scientific understanding of cardiac physiology at the time in which the intervention to decrease arrhythmias after a myocardial infarction (heart attack) unexpectedly resulted in increased mortality. It is difficult not to note, however, that Dr. Prasad doesn’t explain how his approach of dismissing or downplaying biology would have avoided the need to carry out this particular trial given what was known at the time about arrhythmias after heart attacks or how he would have discovered that the routine use of these drugs (class I antiarrhythmic drugs) might increase mortality after acute myocardial infarction without the clinical trial. So why did the trial fail? The reason turned out to be that in the setting of myocardial infection these drugs, rather than decreasing arrhythmias, actually generate arrthymias, some of which can be fatal,. Moreover, contrary to what Dr. Prasad argues, a counterargument can be made that the reason this trial failed because of inadequate consideration of preclinical and basic science suggesting that perhaps these drugs could generate arrhythmias in the context of a myocardial infarction, not adherence to “biological dogma.”

Here’s what I mean, starting with the abstract of a 1994 paper on the trial:

Although active treatment in CAST-I was associated with greater mortality than placebo with respect to almost all baseline variables, the therapeutic hazard was more than expected in patients with non-Q-wave myocardial infarction and (for total mortality) frequent premature VPDs and higher heart rates, suggesting that the adverse effect of encainide or flecainide therapy is greater when ischemic and electrical instability are present. The relative hazard of therapy with moricizine in the sicker CAST-II population was greater in those using diuretics. Thus, although these drugs have the common ability to suppress ventricular ectopy after myocardial infarction, their detrimental effects on survival may be mediated by different mechanisms in different populations, emphasizing the complex, poorly understood hazards associated with antiarrhythmic drug treatment.

Later in the paper, it is noted that in animal models of cardiac ischemia (low blood or blocked blood flow), these drugs increased arrhythmias and death in the experimental animals who received them. I’m not a cardiologist or an expert in cardiac ischemia, but one wonders if the results of these animal studies might have predicted the problem seen in this trial. I don’t claim that they did, but to hold up this trial as an example of a clinical trial whose results radically changed our understanding of biology strikes me as reaching a whole heck of a lot. Maybe my take is incorrect, but I don’t think I’m incorrect to suggest that this is not a great example of our understanding of biology being totally changed by the results of a clinical trial; rather, it sounds like more of a refinement. Cardiologists and/or cardiac physiologists who might be reading can correct me if I’m wrong.

None of this justifies Dr. Prasad’s broad claim:

In essence, we’re arguing for a reordering of priorities in medical education. While the knowledge of biology and anatomy is crucial, it should not overshadow the importance of evidence-based medicine. By introducing students to the principles of evidence-based medicine early on, we can create a generation of doctors who put patient outcomes first, regardless of biological plausibility. It’s not a case of one over the other; it’s about getting the sequence right.

No, clearly to Dr. Prasad it is a case of one over the other, with EBM being more important, or “getting the sequence right,” so much so that Dr. Prasad wants it taught first. Also Dr. Prasad advocates EBM “first, biology and anatomy later,” but how can a student actually approach EBM claims without a knowledge of biology and anatomy? For a simple example, how would one approach a knowledge of the EBM basis for surgical procedures for gallstones and cholecystitis without a knowledge of gallbladder and biliary tree anatomy? How would one approach the EBM basis of chemotherapy for various cancers—or pick just one!—absent a basic science understanding of the molecular basis of the specific cancer being considered and the biological mechanisms of action of the drugs used?

One of Dr. Prasad’s commenters put it well:

I have to say I disagree with Vinay on this one. In order to understand the underlying basis of medicine, you have to know some basics physiology (including neuroscience), anatomy and biochemistry. That provides one with the tools to think critically which is so crucial when it comes to evidence-based medicine and RCTs. That’s especially so when not all RCTs are created equal or done correctly (as indeed Vinay continually points out when it comes to cancer drugs).

Personally, as an advocate of SBM, I tend to agree with this commenter, with one exception, namely that there is no “may” about it:

Vinay may be setting up a false dichotomy. Doctors need to be trained on how to integrate and coordinate their knowledge of biology, pathology, anatomy, etc with their knowledge gained from reading reports of RCTs.

This is almost a statement of what SBM is about! He’s so close. I would say that doctors should be able to integrate their knowledge of basic and preclinical science with RCT results in order to assess the probability that a given RCT has produced an accurate reflection of the efficacy and safety of an intervention—in other words, Bayesian reasoning that takes into account not just RCTs.

Methodolatry versus SBM

Dr. Prasad’s “modest proposal” is at its heart methodolatry writ large. To him EBM is RCTs. (If Dr. Prasad accepts that EBM is and should be more than just RCTs, he gives no hint of it.) Basic science doesn’t matter much, his protestations otherwise that it is just as important (but should be taught only after EBM) notwithstanding. Indeed, it’s hard not to look at his entire proposal as a way to indoctrinate students into a version of EBM that is at its heart methodolatry and then “backfill” (as he puts it) this narrative with basic science that supports it. Whether he realizes it or not, Dr. Prasad is supporting a model that has long been used to misrepresent quackery as potentially effective and put it on steroids. I suppose that I shouldn’t be surprised, as this is a doctor who has long dismissed debunking of quackery and antivax misinformation as a waste of time. Unfortunately, now he has become a poster child for why this debunking is so difficult and necessary, even as he himself complains about criticism of his many dubious pronouncements about the pandemic.

I do think that more training in clinical trial methodology in medical school would be very helpful. Truth be told, three decades ago there wasn’t very much training of this sort in my medical school curriculum, although I am told that there is more now. The problem is that, contrary to what methodolatrists like Dr. Prasad argue, it is impossible to contextualize RCT findings without a solid grounding in basic anatomy, physiology, and biochemistry. Rather than separate the two, I would argue that medical education need more just plain science, including basic and clinical science, plus much more critical thinking. Dr. Prasad, for all his critical thinking about oncology trials in the past, shows that his critical thinking is very selective, and a physician’s clinical thinking about medicine and RCT results should be much broader—as well as based in science.

ADDENDUM May 23, 2023: Yesterday, Dr. Prasad wrote a post for his Substack stating that his entire post had been written by Chat GPT, the AI chatbot that’s been in the news so much lately:

I am actually writing this column. But I did not write a column that appeared last Friday, entitled Rethinking Medical Education. That column was 100% written by Chat GPT.

It all got started with Timothee Olivier. He had a wild idea. He asked Chat GPT to write a column in my style. (Below is his verbatim prompt). He suggested I post it to see the response. He made no edits to it. The column I posted was that.

When I read it the first time, it sounded a lot like something I would say. Because I said something similar 10 years ago. That article was published in academic medicine. Of course, Timothee knows my views on this topic, so he gave some guidance. At the same time, the essay that Chat GPT wrote is different than what I would write. It is drastically different than my 2012 essay.

I have to admit that while reading it, although I thought it was one of Dr. Prasad’s lesser efforts, from both the standpoint of style and argument, it didn’t occur to me that he hadn’t written it. No doubt Dr. Prasad, if he’s seen my post at all, is chuckling at putting one over on me. However, before you think I screwed up, just look at this prompt that was used, as described in his “revelation”:

Hello, ChatGPT, could you write a 1000 words essay, in the style of Vinay Prasad, MD- MPH, writing in the style of his personal substack, punchy as usual. The whole idea of the essay would be that medical training should be shorter, but focused on evidence-based medicine and patient’s care very early on. One paragraph would be about the fact that because biology made great advances during the 20th century, it became central in medical education. The second paragraph should emphasize that the other main pillar of medicine that occured in the 20th century is evidence-based medicine, with randomized clinical trials at its core. Third, we should underline that timing in the curriculum matters : if students are first tought about the primacy of biology, they will later reject evidence-based result based on implausibly biological findings, yet what matters to patients is what is beneficial to them, whatever the biological reason. In a last paragraph, Vinay would argue that the medical curriculum should start with history of medicine, great principles of trials, examples of medical reversal, when biology was later reverse in randomized clinical trials like in CAST, and that medical eduction should stand first on evidence-based principle before teaching basic principles of biology and anatomy. Make more paragraphs than less if necessary. Avoid the term “paradigm shift”. The style has to be easily understandable for lay people also. The first sentences should be short and clear about the whole argument of the essay.

So Olivier and Prasad basically told Chat GPT what to write and how to write it, using a prompt that is, at just under 250 words, one quarter of the word count of the final essay. In fact, the Chat GPT prompt is so long and detailed, that Dr. Prasad might as well have written the damned post himself, as it probably took as much work to come up with that prompt as it would have just to write the post. It also makes it very clear that, even if the actual essay was written by Chat GPT, it is basically Dr. Prasad’s argument. His prompt tells you that it was, as he and Olivier basically laid down very clear instructions for what the chatbot should write and even some phraseology that should be included. I also assume that he wouldn’t have posted it if he had major problems with it. So, ChatGPT or no ChatGPT, this is clearly nothing more than one of Dr. Prasad’s bad arguments.

I’ll also note that I’ve tried the same sort of experiment with Chat GPT and been very much less impressed with the results. (It’s not as though there isn’t a copious amount of verbiage for the chatbot to train on to mimic my style, either.) For instance, I once asked it to write a post in my style about why homeopathy is impossible, and it sounded nothing like me. Maybe I should try again.