When my son was very young, like many children, he had a terrible time sleeping at night. Some nights I had to crawl out of his bedroom on my hands and knees so he wouldn’t sense me leaving and wake up. If I was lucky there was an hour of two of respite, before the cycle began again. Sleepless nights left us all cranky and exhausted. It got better, but it seemed to take years. Parents who deal with sleeplessness in children understandably worried about the causes and consequences of what they feel is persistent or atypical insomnia. While there are lots of folk remedies and tips, many are understandably apprehensive about “medicating” their child to help them sleep. Tell someone there’s a “natural product” for sleep, and you can expect a lot of interest. That’s what’s happened with melatonin, a hormone that is sold without a prescription in the United States, and other countries. Stores have shelves of melatonin, many in dosage forms designed for just for children, like gummies.

When my son was very young, like many children, he had a terrible time sleeping at night. Some nights I had to crawl out of his bedroom on my hands and knees so he wouldn’t sense me leaving and wake up. If I was lucky there was an hour of two of respite, before the cycle began again. Sleepless nights left us all cranky and exhausted. It got better, but it seemed to take years. Parents who deal with sleeplessness in children understandably worried about the causes and consequences of what they feel is persistent or atypical insomnia. While there are lots of folk remedies and tips, many are understandably apprehensive about “medicating” their child to help them sleep. Tell someone there’s a “natural product” for sleep, and you can expect a lot of interest. That’s what’s happened with melatonin, a hormone that is sold without a prescription in the United States, and other countries. Stores have shelves of melatonin, many in dosage forms designed for just for children, like gummies.

Natural, but not really

In the early 1900s it was observed that the pineal gland secreted a substance with physiologic effects, and the hormone itself was named in 1958. Receptors for the hormone have been identified in the hypothalamus, the pituitary, and in other organs in the body. And it’s definitely a natural substance: melatonin is found in vertebrates, invertebrates, animals, bacteria, fungi, algae and plants. In humans and other mammals, melatonin secretion by the pineal gland follows the light cycle, being low during daylight hours, surging in the evening and peaking in the middle of the night. This secretion starts in infancy and continues through adulthood, followed by a decline as we age. As a therapeutic drug, melatonin has been explored in clinical trials mainly for the prevention and treatment of sleep disorders like insomnia and jet lag. The evidence overall suggests melatonin is modestly effective. It seems to be most effective for sleep-onset insomnia, and may give a slight increase in total sleep time. In children, melatonin may be recommended for long-term use in autism spectrum disorder and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder.

The regulation of melatonin varies around the world. In some countries, it’s regulated like a drug, and manufacturing is held to the same quality standards. Melatonin supplements in the United States are not subject to prescription drug manufacturing standards. This is despite the fact that most commercial melatonin supplements contain a laboratory-synthesized active ingredient. The Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act of 1994 (DSHEA) established the regulatory framework for dietary supplements. It effectively excludes manufacturers of these products from virtually all regulations that are in place for prescription and over-the-counter drugs. Under DSHEA, the FDA may not approve dietary supplements for safety and effectiveness before they are marketed. The FDA can only intervene to pull products off the market, after they are marketed, and only if they are adulterated or misbranded.

Earlier this year, I described one of the apparent effects of this regulation: A variety of melatonin “gummies” were analyzed. In a sample of 25 different brands, one product contained no melatonin at all but contained 31.3mg of CBD. Among the remaining products, the actual quantity of melatonin ranged from 74% to 347% of the labelled content. Overall, 88% of the products where inaccurately labelled. Only 3 products contained melatonin that was +/- 10% of the labelled content. Inconsistent product quality means it isn’t possible for parents to know what dose of melatonin they’re actually giving to their children.

The unreliable manufacturing standards along with growing usage may be contributing factors in the observation that poisonings in children are increasing. In 2020, melatonin also became the most frequently-reported pediatric poisoning reported. Between 2012–2021, the annual number of pediatric ingestions of melatonin increased by 530%. While most poisonings had few or no harms, some did have very serious outcomes, including hospitalization and death.

Use in children and adolescents

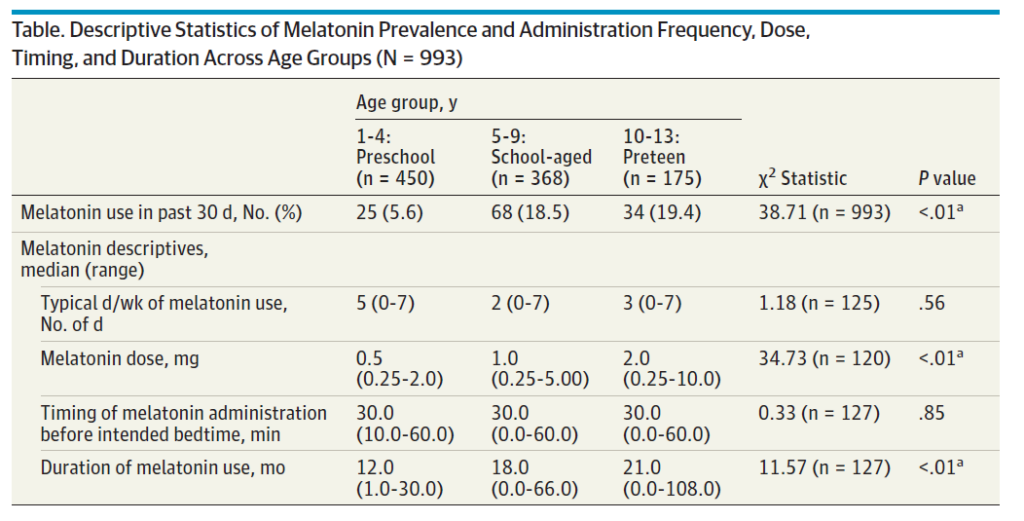

A new paper by Lauren Hartstein and colleagues at the University of Colorado Boulder was published last week in JAMA Pediatrics. It describes the results of a survey of parents of children aged 1-14 which queried sleep practices and melatonin use in the past 30 days. Data was collected over three months in early 2023. Data was collected for 933 children and adolescents, 53% femail with a mean age of 6. The main results were as follows:

Almost one in five children aged 5-9 had been given melatonin in the past 30 days. What’s also interesting is that children in all age groups are receiving melatonin, some continuously (7 days per week). The melatonin dosage increased across age groups, ranging from a median of 0.5mg in preschool children to 2 mg in preteens. Among preschool children who had taken melatonin in the past 30 days, the median duration of usage was 12 months. This duration extended to 18 months for school-aged children and 21 months for preteens. In terms of the preferred form of melatonin, across all age groups, the majority used gummies (64.3%), followed by chewable tablets (27.0%), pills (6.3%), and liquid (2.4%).

The survey results suggest widespread use of melatonin among children and adolescents in the United States, with some parents using it in very young children. The popularity of child-friendly melatonin forms, such as gummies, may be contributing to the increased usage. Moreover, parents may administer melatonin for an extended duration, often exceeding 12 months.

What do we know about the safety of melatonin in children and adolescents?

According to the Natural Medicines Database, melatonin in children is considered possibly safe when taken orally in low doses for a short duration. It has been studied in clinical studies with doses up to 12 mg per day. Concerns have been raised regarding the potential impact of melatonin on gonadal development in children, although evidence supporting this is limited and primarily based on three small observational studies with inadequate follow-up and imprecise measures of pubertal timing. Pediatric overdoses are rare but possible, emphasizing the need for careful use. Overall, melatonin is recommended to be reserved for children with a specific medical indication and not employed to induce sleep in otherwise healthy children. There is a lack of information on the long-term safety of melatonin use in children.

Conclusion

Melatonin is widely considered innocuous, safe, and effective, and its use has exploded. This survey provides more information on the use of melatonin in children. Some of that usage appears prolonged. Considering the manufacturing and quality issues with melatonin supplements, and the lack of long-term safety information, this paper raises additional concerns about the popularity of melatonin. More information is needed, especially in children.