Early in the pandemic, and in the absence of any convincing evidence, hydroxychloroquine and later ivermectin were promoted as potential cures for COVID-19 infections. Despite multiple statements from FDA and other organizations, there was a significant increase in the demand for these products and also their prescription rates. A drug which is clinically ineffective, but has side effects, is arguably harmful, and both ivermectin and hydroxychloroquine met these conditions. Their use consequently contributed to worse outcomes and unnecessary expense for users.

Given the negative consequences of non-evidence-based treatments during a pandemic, Roy Perlis and associates sought to quantify both the prevalence of the use of these treatments, and the relationship with endorsement of misinformation, or of lack in trust in scientists and physicians. If health professionals and public health organizations want to improve their messaging and help connect people with good health information, we need to understand what drives people to use treatments that are ineffective. The paper was published on September 29, 2023 in JAMA Health Forum, and reveals some interesting relationships about the characteristics of those that used these treatments.

The Study

This analysis pulled data from December 2022 through January 2023 from the COVID States Project, a consortium that has conducted a 50-state internet survey every 4-8 weeks since spring 2020. Survey respondents were 18 years or older and resided in the USA. The survey sought to meet representative representation for race, ethnicity, age and gender.

Participants were asked if they had been diagnosed with COVID-19, or believed they had previously been infected. The primary analysis included all of those that answered “yes”. Participants were then asked if they had taken hydroxychloroquine, ivermectin, or an FDA-approved antiviral medication. Political affiliation was determined by asking “Generally speaking, do you think of yourself as a…” with Republican, Democrat, Independent, or other as choices. Finally, COVID-19 vaccine–related misinformation was assessed by by presenting respondents with statements about the vaccine; and whether they agreed, disagreed, or were not sure about the statement:

Below are some statements about the COVID-19 vaccines that are currently being distributed. To the best of your knowledge, are those statements accurate or inaccurate?

The COVID-19 vaccines [accurate/inaccurate/not sure]:

- will alter people’s DNA.

- contain microchips that could track people.

- contain the lung tissue of aborted fetuses.

- can cause infertility, making it more difficult to get pregnant.

- contain a bioluminescent marker used to trace people.

Trust in institutions was evaluated by asking how much respondents trusted a given group to do the right thing:

How much do you trust the following people and organizations to do what is right? [a lot/some/not too much/not at all]:

- Donald Trump

- Hospitals and doctors

- Pharmaceutical companies

- Scientists and researchers

- The news media

- Social media companies

The researchers measured conspiracy-mindedness via the 4-item American Conspiracy Thinking Scale:

How much do you agree or disagree with the following statements? [strongly agree/somewhat agree/neither agree or disagree/somewhat disagree/strongly disagree]

- Even though we live in a democracy, a few people will always run things anyway.

- The people who really ‘run’ the country are not known to the voters.

- Big events like wars, the current recession, and the outcomes of elections are controlled by small groups of people who are working in secret against the rest of us.

- Much of our lives are being controlled by plots hatched in secret places.

Finally, the researchers examined sources of news by asking whether individuals had received any news about COVID-19 in the prior 24 hours from a list of sources including Facebook, CNN, Fox News, MSNBC, and Newsmax.

The Results

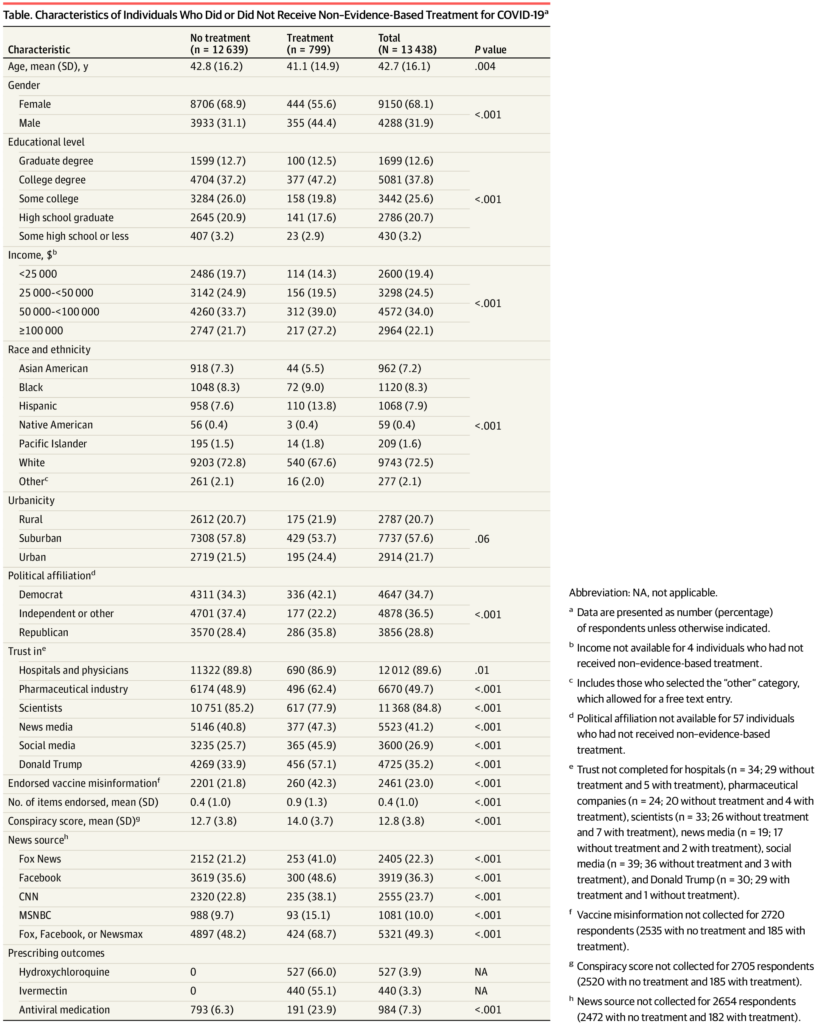

Here are the characteristics of those that did or did not use non-evidence-based-treatments. Overall, 799 (5.9%) reported the use of at least one non-evidence-based treatment, compared to 7.3% that reported uses of an FDA-approved treatment. Interestingly but perhaps not surprisingly given the “horse paste” comments and photos that circulated at the time, as many as 30% of individuals using ivermectin and 14% of individuals using hydroxychloroquine reported that they did not receive these interventions from a medical professional.

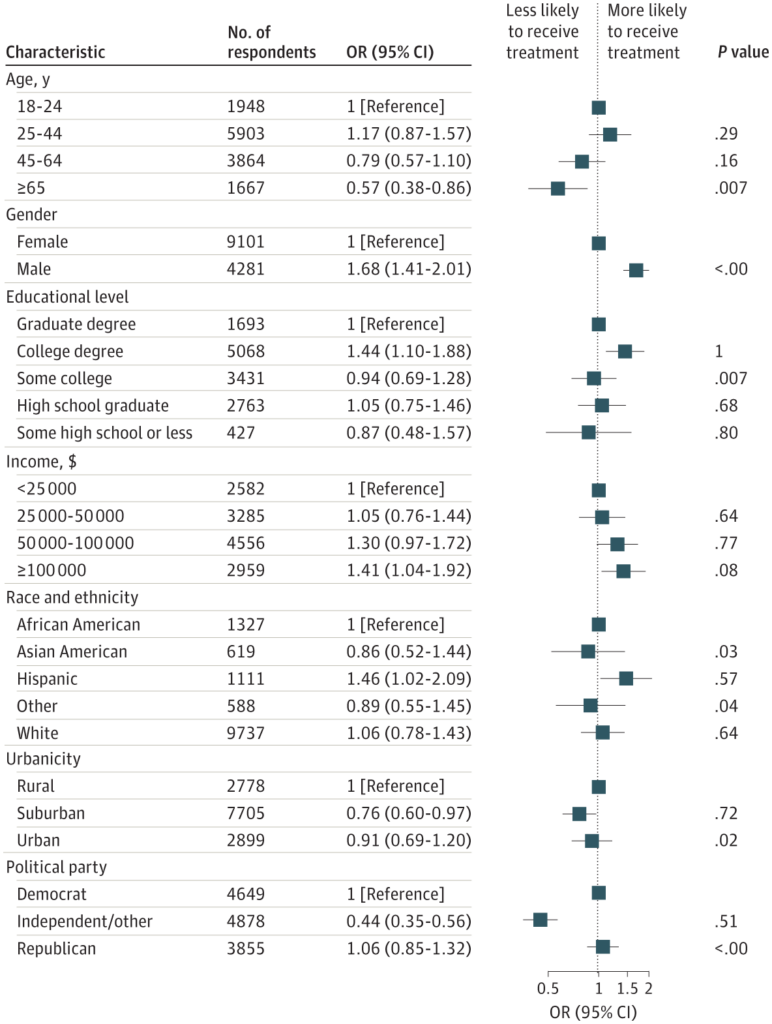

The table shows that those that used these treatments were more likely to be male and more likely to have a higher income. More education seems to bias towards treatment. Both Democrats and Republicans were more likely to use these treatments vs. independents. Users also tended to be heavier consumers all the media sources reported, compared to non-users.

With respect to the connection between endorsing misinformation related to vaccines and the use of non-evidence-based medications, 2,461 out of 10,718 individuals (23.0%) expressed their support for at least one aspect of vaccine-related misinformation. In survey-weighted regression models, this endorsement was linked to a notably higher likelihood of having used non-evidence-based treatments. In adjusted models, but not in unadjusted ones, misinformation was modestly but significantly linked to the receipt of prescription antiviral treatments.

With respect to the connection between endorsing misinformation related to vaccines and the use of non-evidence-based medications, 2,461 out of 10,718 individuals (23.0%) expressed their support for at least one aspect of vaccine-related misinformation. In survey-weighted regression models, this endorsement was linked to a notably higher likelihood of having used non-evidence-based treatments. In adjusted models, but not in unadjusted ones, misinformation was modestly but significantly linked to the receipt of prescription antiviral treatments.

Users reported substantially more trust in social media and Donald Trump, but also in the pharmaceutical industry, with less trust in scientists. Trust in hospitals and physicians was linked to a reduced likelihood of using non-evidence-based treatments, but an increased likelihood of receiving antiviral treatment. A similar trend was observed with trust in scientists, where greater trust was associated with a reduced likelihood of using non-evidence-based treatments and an increased likelihood of receiving antiviral treatment. Interestingly, the presence of trust was connected to a higher likelihood of using either non-evidence-based or antiviral treatments, although the magnitude of these effects varied considerably.

Not just political persuasion driving use

The findings from this research align with other research that examined prescription data for ivermectin and hydroxychloroquine, showing an increase in use during the early stages of the pandemic. Notably, this paper identified a significant proportion of these treatments were obtained without a prescription from a medical professional, emphasizing the limitations of relying solely on prescription data to estimate use.

Other studies using county-level data have linked higher support for Donald Trump with a greater prevalence of non-evidence-based COVID-19 prescriptions. Similarly, research has also suggested that more politically conservative physicians were more inclined to prescribe them. Importantly, this study shows that use was not simply a matter of political affiliation. Drivers of use included the endorsement of vaccine-related misinformation, a lack of trust in healthcare institutions and scientists, and a tendency towards conspiratorial thinking related to politics.

Disappointingly, almost one quarter of the American population believes inaccurate information related to COVID-19, with specific subgroups being more inclined to do so. Embracing COVID-19-related misinformation may reduce the willingness to be vaccinated, an intervention which has been shown to reduce the likelihood of harms from COVID-19 infections. False information is predominantly disseminated online and regrettably during the pandemic, by political figures and media outlets. Interestingly, watching cable news (regardless of that channel’s perspective) were associated with increased odds for treatment: both evidence-based and non-evidence based.

The authors conclude that misinformation may not only reduce the likelihood of vaccination but may drive the use of ineffective and possibly harmful treatments like hydroxychloroquine or ivermectin. How we get to a better place, from a public health perspective, is less clear. Refuting misinformation feels more challenging than ever before, and we need better strategies – to manage the ongoing harms of this pandemic, and to prepare for the next one.