There’s a misconception that I frequently hear about evidence-based medicine (EBM), which can equally apply to science-based medicine (SBM). Actually, there are several, but they are related. These misconceptions include the idea that EBM/SBM guidelines are a straightjacket, that they are “cookbook medicine,” and that EBM/SBM should be the be-all and end-all of how to practice clinical medicine. New readers might not be familiar with the difference between EBM and SBM, and here is not the place to explain the difference in detail because this post isn’t primarily about that difference. However, for interested readers, a fuller explanation can be found here, here, here, and here. The CliffsNote version is that EBM fetishizes the randomized clinical trial above all other forms of medical investigation, a system that makes sense if the treatments being tested in RCTs have a reasonably high prior probability of translating to human therapies based on basic science mechanisms, experimental evidence in cell culture, and animal experiments. Using Bayesian considerations, when the prior probability is very low (as is the case for, for example, homeopathy), there will be a lot of false positive trials. Such is how EBM was blindsided by the pseudoscience of “complementary and alternative medicine” (CAM) or, as it is called now, “integrative medicine.”

However, for purposes of this post, SBM and EBM can be considered more or less equivalent, because we are not going to be discussing CAM, but rather widely accepted treatment guidelines based on science, both basic and clinical trial science. I merely mention this difference for completeness and for new readers who might not be familiar with the topics routinely discussed here. For purposes of this post, I’m talking evidence-based guidelines from major medical societies. More specifically, I want to address the disconnect between what patients often want and what our current guidelines state. It’s not just patients either, but doctors; however, for purposes of this post I’m going to focus more on patients. It’s a topic I’ve addressed before, in particular when it comes to breast cancer, where I’ve discussed changes in the mammography screening guidelines and Choosing Wisely guidelines for breast cancer. There are many other examples that I haven’t discussed.

What got me thinking about this again was an article by Don S. Dizon, MD, FACP, Associate Professor of Gynecologic Oncology at Harvard Medical School, appearing in the ASCO Post entitled “Evidence Should Inform Guidelines, Not Be Used as a Mandate.” While I agree with a lot of what Dr. Dizon writes, I also have a couple of nits to pick as well, but first let’s see what he wrote.

Early detection of cancer recurrence: Evidence versus patient wishes

While cancer patients are understandably overjoyed when their treatment successfully puts them into remission, they are equally understandably frightened as well. What terrifies them, of course, is the fear that their cancer will recur to claim their lives. It’s not an unreasonable fear, either, because even for early stage invasive breast cancer, which is highly successfully treated, long term survival is well over 90%, which means that 5-10% will still recur in their lifetimes despite the best efforts and maximal therapy. For higher stages of breast cancer and other cancers, the risk is higher. As the years go by and patients pass the five year mark, that fear will tend to recede, but it never goes away, particularly for hormone receptor-positive breast cancer (for example), which is notorious for recurring late, sometimes as late as 20 years later. Here’s where patient wishes frequently clash with EBM/SBM. Patients naturally want to be monitored frequently and aggressively for recurrence. However, for many cancers oncologists know that, paradoxically, early detection of recurrence does not impact survival.

This is true, for example, for ovarian cancer, and Dr. Dizon, being a gynecologic oncologist, begins with one of his patients, whom he calls “Jody.” Jody was treated two years ago for a rare form of ovarian cancer. At surgery, fortunately it was confined to the pelvis and had not spread to the abdomen. She then underwent chemotherapy, and her CA-125 levels fell with each cycle until her CA-125 was within the normal range. CA-125 is a tumor marker frequently elevated in ovarian cancer and useful for following response to therapy. If therapy doesn’t drop CA-125 to normal, chances are that there’s residual disease. Also, frequently, a rising CA-125 level is the first indication of recurrence, which made it very attractive for oncologists to follow CA-125 levels after successful treatment of ovarian cancer.

With that background in place, Dr. Dizon continues:

At her first post-chemotherapy visit, I relayed the results of her CA-125 and CT. “Based on both, you are now in remission.”

“Wow,” she said. “I am so relieved this is over. What comes next, though?”

At that point I discussed her follow-up. “Your risk of recurring will be greatest in the next 3 years,” I said. “As such, I’d like you to be seen here every 3 months for a physical exam that will include a pelvic. I really wouldn’t recommend anything more.”

“Wait—no blood tests? What about imaging?” she asked.

These are, of course, perfectly reasonable questions, questions that virtually every cancer patient asks when confronted with a post-therapy screening regimen that strikes them as insufficiently aggressive. After all, intuitively, it seems “obvious” to most people that early detection of a recurrence should lead to better outcomes, just as it is intuitively “obvious” to most people that early detection of cancer in a healthy population should lead to better survival and better outcomes. Yet, as any longtime reader of SBM knows, that is often not the case. Thanks to overdiagnosis (the diagnosis of subclinical disease that would never progress to harm the patient), lead time bias (how screening can give the false appearance of prolonging life even in the absence of effective treatment), and length bias (the bias in screening towards picking up indolent, slowly progressing disease), the relationship between early detection and prognosis is not nearly as clear as “intuition” leads us to believe. In other words, more is not necessarily better, the assumption of even doctors that failure to screen kills their patients. The reality is that screening for cancer (or any disease) in asymptomatic people can help, but it can also harm. Most patients (and, unfortunately, a lot of doctors) don’t understand that.

Many of these considerations come into play in screening a cancer patient for recurrence after she has been successfully treated to bring her cancer into remission, although the difference is that the incidence of recurrence will be much higher in such patients than the incidence of the disease is in asymptomic patients never before diagnosed with cancer. It’s also why, for most cancers, evidence-based guidelines no longer recommend intensive screening for recurrence after successful treatment, as is the case for ovarian cancer, which Dr. Dizon tried to explain to his patient:

“Well,” I answered, “the data suggest that nothing else will be very helpful. I know we measured your CA-125 during treatment, but it was to help me guide the impact of chemotherapy. After treatment, a large randomized trial done in the United Kingdom showed that routinely measuring CA-125 isn’t helpful. In that trial, women entering remission agreed to have their CA-125 levels checked but the results were masked. If their CA-125 rose above twice the upper limit of normal, patients were randomly assigned to one group who were told their CA-125 and asked to start chemotherapy as soon as possible (called the “early” chemotherapy group) or to another group who were not told their CA-125 and only started chemotherapy when clinical or symptomatic relapse was diagnosed (called the “delayed” chemotherapy group). The upshot is that overall survival was no different between either group. The only impact was that women in the early chemotherapy group experienced worsening of their perceived health sooner than those treated in the delayed group.”

“Therefore,” I concluded, “on the basis of pretty good data, it would be very reasonable not to follow your CA-125 if you are feeling well. However, if you develop any symptoms at all, or if you are worried at some point, we could certainly check it. As for imaging, I wouldn’t subject you to CT scans at regular intervals if you feel well. If we do a scan, it should be because there’s a question or a concern.”

This is the study to which Dr. Dizon was referring. There were 1,442 patients in the study, and its conclusions were about as unequivocal as one can get in a study:

Our findings showed no evidence of a survival benefit with early treatment of relapse on the basis of a raised CA125 concentration alone, and therefore the value of routine measurement of CA125 in the follow-up of patients with ovarian cancer who attain a complete response after first-line treatment is not proven.

To repeat: The only effect of screening CA-125 and treating early based on a biochemical increase in the level of the tumor marker was more treatment with chemotherapy and a longer period of time with a recurrence before death.

Ovarian cancer is not alone

It’s not just ovarian cancer for which intensive screening is not recommended after curative treatment has successfully resulted in cancer remission. In fact, after a period of time a couple of decades ago when we were routinely screening patients for recurrence, we’ve learned again that more is not necessarily better and that less can be more. Consider Choosing Wisely, a program initiated by the American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM) Foundation that challenged medical professional societies to identify and publicize medical practices that are not evidence-based but nonetheless common. (Given my tendencies, I can’t help but contrast Choosing Wisely to how practitioners of CAM pretty much never urge their members to abandon practices that aren’t evidence-based, but I digress, if only slightly.) Among these first five guidelines was this:

Don’t perform surveillance testing (biomarkers) or imaging (PET, CT, and radionuclide bone scans) for asymptomatic individuals who have been treated for breast cancer with curative intent.

- Surveillance testing with serum tumor markers or imaging has been shown to have clinical value for certain cancers (e.g., colorectal). However for breast cancer that has been treated with curative intent, several studies have shown there is no benefit from routine imaging or serial measurement of serum tumor markers in asymptomatic patients.

- False-positive tests can lead to harm through unnecessary invasive procedures, over-treatment, unnecessary radiation exposure, and misdiagnosis.

That was 2012. What about now? Well, ASCO has doubled down, recently extending the recommendation to basically all cancers, at least as far as advanced imaging, such as CT and PET scans go:

Avoid using PET or PET-CT scanning as part of routine follow-up care to monitor for a cancer recurrence in asymptomatic patients who have finished initial treatment to eliminate the cancer unless there is high-level evidence that such imaging will change the outcome.

- PET and PET-CT are used to diagnose, stage and monitor how well treatment is working. Available evidence from clinical studies suggests that using these tests to monitor for recurrence does not improve outcomes and therefore generally is not recommended for this purpose.

- False positive tests can lead to unnecessary and invasive procedures, overtreatment, unnecessary radiation exposure and incorrect diagnoses.

- Until high level evidence demonstrates that routine surveillance with PET or PET-CT scans helps prolong life or promote well-being after treatment for a specific type of cancer, this practice should not be done.

There are exceptions, one of which, at least, leads to some disagreement with the ASCO Choosing Wisely guideline above. For example, for colorectal cancer, for high risk patients with colorectal cancer (stage II or III) treated with curative intent, there is high level evidence that intensive surveillance can be beneficial for high risk patients (stages II and III) treated for cure with normal CEA levels and no evidence of disease on scans—although that even has its caveats. For example, the authors of the guidelines for surveillance after treatment of colorectal cancer caution:

Seven meta-analyses have addressed the relationship between intensive surveillance and survival following re- section of colorectal cancer2,23–28 (table 2) including an updated Cochrane analyses.28 All meta-analyses report increased curative resections and improved survival in patients undergoing more intensive surveillance. One meta-analysis,2 which included the largest number of cases (n = 2923), reported that more intense follow-up was associated with increased curative resection rate (24.3% vs 9.9%) and improved survival (78.2% vs 74.3%). In the most recent Cochrane analysis, improved chance of curative surgery for recurrence was associated with higher intensity of surveillance (OR, 2.41; 95% Ci, 1.64–3.54).28 however, there are difficulties with evaluating these studies because testing modalities and the definitions of “intense follow-up” vary. When evaluating the RCT and meta-analyses data in total, it appears that curative resection for recurrence uniformly increases with increased surveillance, whereas the survival advantage is more variable, and likely modest at best.

Another exception: Surveillance colonoscopy is recommended every year for five years for patients with colorectal cancer treated with curative resection.

I could go on with multiple other examples, but the point remains. For the vast majority of cancers, intensive screening after curative treatment does not result in prolong survival, and, even when there is evidence that it does, such as in colorectal cancer, the survival benefit reported is variable and at best very modest. That means that the overall message to oncologists for most cancers is: Don’t be ordering CT scans every six months or following tumor markers every three months. It’s a viewpoint that oncologists have resisted but are finally coming around to. It’s also a viewpoint that is not popular with patients, as you will see.

Dr. Dizon’s patient reacts

Consistent with what I’ve been saying, Dr. Dizon’s patient was not—shall we say?—enthusiastic about his recommendation:

She had looked at me then, not quite sure what to make of this. “Okay, but if I want my CA-125 checked every 3 months you’d do it?”

“Yes, I would,” I said. “I just wanted to make sure you had all the information you needed to make that decision.”

“Fine,” she continued. “I would really prefer we checked my CA-125 when I came in for my exams. It just doesn’t make sense to me that it wouldn’t be helpful.”

See what I mean by these new data being counterintuitive? Most patients react that way, and it often requires a fair amount of explaining and cajoling to reassure the patient that doing a bunch of expensive tests (or even a relatively inexpensive blood test many times) will not benefit the patient, at least not in terms of overall survival, and is likely to negatively impact her quality of life. On the other hand, anxiety is a powerful motivator, and, if it is intense enough, can rub off on even the most experienced clinician armed with piles of evidence from well-designed clinical trials to support his recommendations.

Here’s what happened next at a later visit by the patient for followup after her having persuaded Dr. Dizon to do regular CA-125 levels:

Unfortunately, her CA-125 result came back markedly elevated. I called her and gave her the results, recommending that we get a CT scan. She agreed.

Jody returned to my office the following week. Her CT showed new growth in her abdomen, consistent with peritoneal disease. I started to review options for treatment, but she stopped me. “I just need you to know that I am angry,” she said. “Thank God I asked to have my CA-125 followed—it’s how we picked up this disease. I can’t even imagine where I’d be had I taken your advice and didn’t do bloodwork and just waited for symptoms. Who on earth would follow such advice? It’s like you had asked me to put my head in the sand and ignore what was going on around me. I’m sorry, but I could never do that—and it turns out, I was right.”

I wasn’t prepared for her anger, especially about a conversation we had had years earlier, but I also knew that rehashing the data would serve no purpose. So, instead of going through the data once more, I did what I thought was best. I apologized:

“Jody, I am sorry that you had felt like I was imposing a recommendation on you. It was not my intent. I had hoped to let you know of your options, so that, together, we could choose a surveillance strategy that made sense to you. To do it, I wanted to make sure you knew that there was data available. If it came across any other way, then I take responsibility.”

Whether this was the right course of action or not, I’m not sure. One could certainly argue that that visit wasn’t the right time for Dr. Dizon to point out that he had done nothing wrong and in fact did everything right. As physicians, it is our job to present the best evidence-based treatment recommendations that we can, personalizing them to the patient. Indeed, my main quibble with him is that, at least as he told the story, Dr. Dizon gave in too easily to agreeing to do something that he himself knew not to be purely evidence-based. Personally, although I agree in general with Dr. Dizon’s conclusion, I wasn’t sure, as I read his article, whether Jody was the best example to use to illustrate the principle:

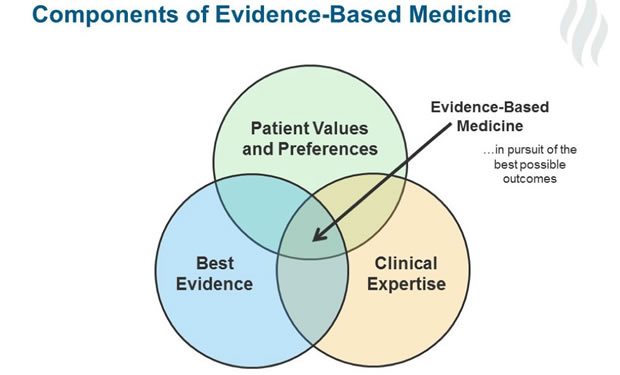

But Jody reminded me once more that evidence has its place, but it’s not gospel. In the end, the data need to be interpreted by our patients, in the context of their own preferences and values, and each person will reach a different conclusion. In the end, evidence should inform our guidance, but it should not be used to enforce mandates.

On the other hand, if the survival outcome is the same regardless of whether one checks CA-125 levels every three months after curative treatment of ovarian cancer or not, one can argue that there wouldn’t be a lot of harm in acceding to the wishes of patients like Jody. Going against that conclusion is evidence that diagnostic tests with a low pretest probability of disease to rule out conditions and reassure the patient actually do little to reassure patients or decrease their anxiety. Indeed, there is actually evidence that more testing increases patient anxiety and certainly leads to higher costs.

Be that as it may, I myself have not infrequently said that a patient’s values matter, using this example. Some patients want to do everything; others value quality of life over quantity. Our job is to give the best evidence-based recommendation that will fit in with the patient’s values. However, in this age where we cannot just ignore cost, a very uncomfortable question always rears its ugly head: How much more are we willing to pay to deviate from evidence-based guidelines to accommodate a patient’s values? If physicians and patients together don’t answer that question, we can be sure that third party payers will.