There’s been a lot of discussion, both in the scientific literature and online, about recent pertussis outbreaks, which are the worst outbreaks in the US in the last 50 years. How could this possibly be, it is asked, when vaccine uptake for the pertussis vaccine remains high? True, there are pockets of vaccine resistance, where uptake of the vaccine is low, but it’s becoming increasingly clear that, unlike the case of measles outbreaks, low uptake of the pertussis vaccine does not appear to be nearly enough to explain the frequency and magnitude of the outbreaks. Given that it’s been a while since any of us has discussed the recent pertussis outbreak here on SBM, I thought that it would be a good time for me to do so, particularly because there have been some new studies and new developments since April, including a paper hot off the presses last Thursday in the New England Journal of Medicine. As a result, those of you who read me at my not-so-super-secret other blogging location might find some of the material in this post familiar, but given the new NEJM paper, I thought that now would be a good time to synthesize and update what I’ve discussed before in different forums in a more comprehensive way, even at the risk of some repetition of previous material I’ve published elsewhere. Hopefully, it will also provide materials for skeptics and supporters of SBM to counter the antivaccine movement, which has pounced on the recent pertussis outbreaks as evidence that the “vaccine doesn’t work.”

Without a doubt (to me, at least), the biggest difference between science-based doctors and quacks is a very simple one. When a treatment or preventative measure isn’t working as well as it should, we science-based physicians ask why. We try to find out what is not working optimally and why. Then we try to figure out how to make things better. So it is with the acellular pertussis vaccine. This vaccine protects against whooping cough, which is caused by Bordetella pertussis, and is administered to children in the form of a combination vaccine, the DTaP (diphtheria/tetanus/acellular pertussis). Five doses are recommended for children, the first at age 2 months, and then at ages 4 months, 6 months, 15-18 months, and 4-6 years. There is also the newer formulation, the Tdap (tetanus, diphtheria, and acellular pertussis), which is recommended for people between the ages of 11 and 64. The Tdap is now usually administered first at age 11-12, with additional recommendations for a Tdap booster in adolescents and adults summarized here, here, and here. Unfortunately, although the vaccine works, recent outbreaks have suggested that we need to change our approach to pertussis vaccination. Let’s see why.

The resurgence of pertussis

It’s no secret that recent outbreaks have been notable for a large contingent of vaccinated children being affected, as has been pointed out in three recent studies. All three indicate that there appears to be a hole in the vaccination schedule that leaves children in the 9-12 year age range inadequately protected against pertussis. Two of these studies suggest that in that age group the attack rate during the recent outbreak in California the attack rate among vaccinated children approached that of unvaccinated children. Antivaccinationists love to cite these studies as smoking gun “proof” that the acellular pertussis vaccine “doesn’t work” and that “natural immunity is better,” but what they always leave out are the findings that the acellular pertussis vaccine in DTaP is quite effective in protecting younger children and in protecting teens who have received the recommended Tdap booster at age 11 or 12. The problem, it appears, is mostly in the range between the last DTaP dose, usually administered around age five or so, and the Tdap booster dose recommended for preadolescents.

First up, let’s look at a study study published last March examining the California pertussis outbreak by David J. Witt and colleagues at Kaiser Permanente. This study found a shorter-than-expected duration of immunity due to the the acellular pertussis vaccine. Basically, as I mentioned before, this study found that the vaccine was highly effective in children between 6 months and five years of age but that its effectiveness waned. The most disturbing part of the study was that it found that that vaccinated children between 10 and 12 were almost as likely to develop pertussis during the outbreak as unvaccinated children:

Among the 58 cases of pertussis in children aged 10-12, 55 (95%) had received five or more doses of pertussis vaccination. Eight of these 58 (14%) children had received their sixth booster-dose prior to onset of disease. In the 13-18 year age group and in the entire cohort of those 2-18 years of age, there was a highly significant increase in cases in unvaccinated children (p = 0.009 and 0.01 respectively). See table 1.

It should be noted that in all age groups, the attack rate in the unvaccinated and undervaccinated groups were higher than in the fully vaccinated group, but that this difference only reached statistical significance in the 13-18 year group, where the attack rate was nearly five times higher in the unvaccinated/undervaccinated group. Moreover, when taken as a whole, the attack rate was also statistically significantly higher in unvaccinated/undervaccinated children from ages 2 to 18. In other words, the vaccine works, but there is a period (age 10-12) during which there appears to be a hole in the coverage, such that waning immunity after the last dose results in decreased protection, protection that is reactivated by the booster dose at 12 years. Indeed, there was a very strong correlation between the interval between onset of pertussis and last acellular pertussis vaccine dose, with the interval peaking at 11 years. The authors conclude:

In the case of the recent California epidemic, it appears that the effectiveness of the current vaccine schedule, when paired with the imperfect vaccination rate, may be insufficient to prevent an epidemic. Earlier vaccine booster doses may be required to provide adequate herd immunity, absent an increase in vaccination rate, efficacy, or durability. Earlier booster doses could prevent immunity from waning, and address disease in the 8-12 age group.

In other words, this study doesn’t show that the vaccine doesn’t work. Rather, it suggests that immunity from the vaccine wanes sooner than expected, that this region of California doesn’t have a high enough vaccine uptake rate to prevent epidemics, and that the vaccination schedule should probably be changed to provide earlier boosters in order to protect older children and teenagers. Indeed, an accompanying editorial by Dr. Alfred DeMaria, Jr. agrees:

Continued widespread outbreaks of pertussis in the United States, with disruption of school and work, as well as with the significant threat to infants, begs the question of more effective use of Tdap on a population level. Experience with Tdap vaccine has diminished concerns about adverse events [12], but the duration of protection with Tdap is not yet known. Reasonable consideration should be given to the suggestion of earlier, more frequent booster doses, as well as the replacement of Td by Tdap as the routine adult “tetanus shot” [13, 14]. With US adolescent Tdap coverage of 69% [15], there is still more to do to achieve full implementation of current recommendations.

Indeed, the second study I mentioned, a study by Winter et al published in July in the Journal of Pediatrics more or less agrees. Basically, it found similar results, specifically a stepwise increase in pertussis among children aged 7-10 years who had completed the DTaP series but who had not yet received the Tdap booster recommended at age 11-12 years, along with a stepwise decrease in cases among adolescents from ages 11 to 14. The authors concluded that preadolescents are susceptible to waning immunity with the current schedule and that the adolescent Tdap dose is effective in protecting younger adolescents.

Again, the conclusion is not that the vaccine doesn’t work, but rather that, given the limited duration of immunity from the acellular pertussis vaccine, our current vaccination schedule is probably not aggressive enough, particularly in children aged 6 to 10, where another booster would likely be a good idea. Moreover, what antivaccinationists tend to completely ignore are observations that, although vaccinated children can still be susceptible to pertussis, they are less infectious, have milder symptoms and shorter illness duration, and are at reduced risk for severe outcomes, such as requiring hospitalization.

Finally, hot off the presses in the current issue of the NEJM is a third study, also out of Kaiser Permanente, that starkly quantifies the waning immunity due to acellular pertussis vaccination. It was a case-control study, in which the authors examined Kaiser Permanente Northern California members who received a pertussis PCR test between January 2006 and June 2011, a time period that includes the last pertussis outbreak in California in 2010. Cases included children who were positive for pertussis and negative for parapertussis by PCR during the study period who also received a fifth dose of DTaP between the ages of 47 and 84 months. These cases were compared to two control groups. The first group consisted of “children who were PCR-negative for both pertussis and parapertussis and who received a fifth dose of DTaP before receiving a negative test result (the PCR-negative controls),” and the second group consisted of “health-plan members who were matched to each PCR-positive child (the matched controls).” Basically, to boil it down to its essence, children diagnosed with pertussis and who had pertussis confirmed by PCR were compared to children who were negative for pertussis on PCR and then to the general population of health plan members. This was a highly vaccinated population (99%), which did not differ between cases and controls. Overall, the study population ended up consisting of 277 children between the ages of 4 and 12 years who were PCR-positive for pertussis, 3,318 PCR-negative controls, and 6,086 matched controls.

One of the big advantages of an health care organization like Kaiser Permanente is that it’s very large (3.2 million members in just Northern California alone) and its databases provide a complete electronic medical record that includes vaccinations and laboratory tests, as well as inpatient, emergency department, and outpatient diagnoses. All of this allows for analyses that would be difficult to carry out otherwise, also because it’s all one health system with standardized care guidelines, which reduces heterogeneity in delivery of care. This is thus about as good as it can get doing epidemiological studies. Also, Kaiser’s members exhibited incidences of pertussis among the various age ranges whose pattern mirrors the patterns observed in the previous two studies I discussed:

During the period from January 2010 through June 2011, when 95% of the cases of pertussis in the study population were diagnosed, the incidence of pertussis was 115 cases per 100,000 person-years among members younger than 1 year of age, decreasing to 29 cases per 100,000 person-years at 5 years of age, sharply increasing to 226 cases per 100,000 person-years at 10 and 11 years of age, sharply decreasing until 15 years of age, and remaining low in persons 15 years of age or older (Figure 1).

In other words, there’s a higher incidence among babies under one year old that decreases through age five but then increases again, peaking at age 10 and 11, before decreasing again. Again, this is consistent with waning immunity of the last DTaP dose at around age 5 or 6. It was a waning of immunity that the authors could quantify:

In the primary analysis comparing PCR-positive children with PCR-negative controls, with adjustment for calendar time, age, sex, race or ethnic group, and medical service area, the odds ratio for pertussis was 1.42 per year (95% CI, 1.21 to 1.66), indicating that each year after the fifth dose of DTaP was associated with a 42% increased odds of acquiring pertussis. A secondary analysis comparing PCR-positive cases with matched controls yielded similar results (Table 2).

What this means is:

In this study, the risk of pertussis increased by 42% each year after the fifth DTaP dose. If DTaP effectiveness is initially 95%, so that the risk of pertussis in vaccinated children is only 5% that of unvaccinated children, then the risk would increase after 5 years by a factor of 1.425 to 29% that of unvaccinated children. The corresponding decrease in DTaP effectiveness would be from 95% to 71%. The amount of protection remaining after 5 years depends heavily on the initial effectiveness. If the initial effectiveness of DTaP was 90%, it would decrease to 42% after 5 years. Regardless of the initial effectiveness, the protection from disease afforded by the fifth dose of DTaP among fully vaccinated children who had exclusively received DTaP vaccines waned substantially during the 5 years after vaccination.

So, basically, what these three studies indicate is that we have a problem with the pertussis vaccine. The question then becomes: What to do about it?

Putting it all together

With respect to vaccines, antivaccinationists frequently willfully invoke the fallacy of the perfect solution (also known as the Nirvana fallacy), which I like to liken to an old sketch Mike Myers back when he was on Saturday Night Live in which he played a Scotsman who would loudly say, “If it’s not Scottish it’s crap.” Basically, under this fallacy, antivaccinationists will argue, in essence, that if a vaccine doesn’t work perfectly 100% of the time, it’s crap. If it isn’t absolutely, positively, 100% safe, it’s crap. If it fails, even just once, to protect against the disease it’s designed to protect against, it’s crap. Never mind that nothing in medicine is 100% effective and safe and that the only certainty in medicine (and life) is that all of us will one day die.

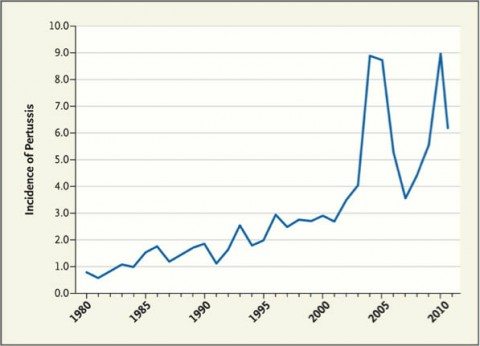

None of this is to say that we shouldn’t strive to improve the acellular pertussis vaccine or improve the vaccine schedule, and that was the topic of a recent paper in the New England Journal of Medicine by Dr. James D. Cherry, a pediatrician at the David Geffen School of Medicine, University of California at Los Angeles, Los Angeles entitled Epidemic Pertussis in 2012 — The Resurgence of a Vaccine-Preventable Disease. He begins by noting that in the U.S. we are currently experiencing what may turn out to be the largest outbreak of pertussis in 50 years, asking the question: Why has this vaccine-preventable disease been on the upswing in recent years? Several answers are forthcoming, but here’s a graph of pertussis versus time:

Cherry first points out that whooping cough is a cyclical disease, with major epidemics every two to five years in the pre-vaccine era. Although vaccination was wildly successful in reducing the incidence from 157 per 100,000 in the 1940s to 1 per 100,000 in 1973, infection does not, contrary to the claims of antivaccinationists that “natural immunity” is permanent, produce lifelong immunity; neither does the vaccine. Cherry notes that this is in marked contrast to, for example, measles, for which immunity due to the vaccine lasts much longer. So now, even though there isn’t as high an incidence of whooping cough, the causative organism, Bordetella pertussis is still circulating in a manner similar to the way it did in the pre-vaccine era. Until recently, it just wasn’t causing epidemics the way that it did before.

Cherry tells us that there are actually two relevant issues to consider: The epidemiology of reported pertussis cases and the epidemiology of pertussis infection. He notes that existing studies suggest that 13 to 20% of prolonged coughs in adolescents and adults are likely due to B. pertussis infection, and studies examining antibody titers suggested an infection rate between 1% and 6%. In other words, there’s a lot of mildly symptomatic pertussis out there, which leads Cherry to ask:

So what are the causes of today’s high prevalence of pertussis? First, the timing of the initial resurgence of reported cases (see graph) suggests that the main reason for it was actually increased awareness. What with the media attention on vaccine safety in the 1970s and 1980s, the studies of DTaP vaccine in the 1980s, and the efficacy trials of the 1990s comparing DTP vaccines with DTaP vaccines, literally hundreds of articles about pertussis were published. Although this information largely escaped physicians who care for adults, some pediatricians, public health officials, and the public became more aware of pertussis, and reporting therefore improved.

Antivaccinationists will no doubt scoff at this suggestion the same way that they scoff at any suggestion that the increased prevalence of autism over the last 20 years could possibly be due to greater awareness and intensive screening programs, but as I’ve pointed out before, it’s a truism in medicine that whenever you look for a disease or condition more carefully you will always find more of it than you did before—sometimes a lot more, particularly if you use more sensitive tests or broaden the diagnostic criteria (the latter of which was done for autism in the early 1990s). As I discussed in the link above, examples abound in medicine in which screening campaigns and more sensitive diagnostic tests have resulted in an apparent increase in prevalence in diseases and conditions without any evidence of a “real” change in their prevalence, as asymptomatic and less symptomatic cases were picked up.

Cherry suggests that one factor behind the rise in pertussis lately is similar:

Moreover, during the past decade, polymerase-chain-reaction (PCR) assays have begun to be used for diagnosis, and a major contributor to the difference in the reported sizes of the 2005 and 2010 epidemics in California may well have been the more widespread use of PCR in 2010. Indeed, when serologic tests that require only a single serum sample and use methods with good specificity become more routinely available, we will see a substantial increase in the diagnosis of cases in adults.

One notes that the last study I cited used the PCR test exclusively to confirm a diagnosis of pertussis infection. Be that as it may, some of what’s going on here might just be overdiagnosis, in which mildly symptomatic cases or cases that aren’t that serious are picked up that once might have been dismissed as a persistent “crud.” Clearly, though, that’s not the only thing going on. Two other issues are likely also contributing. The first is what the three studies I just discussed document, namely waning immunity from the acellular pertussis vaccine. Cherry cites five studies showing that the old DTP (the whole cell pertussis vaccine combination with the tetanus and diphtheria vaccine) was more efficacious than the DTaP (the acellular pertussis vaccine combination), as well as two of the studies above.

Ironically, it is important to remember that the switch from the DTP combination vaccine (nowadays frequently abbreviated DTwP, to denote the whole cell pertussis vaccine) to the DTaP vaccine was largely driven by concerns about the safety of the DTP back in the 1980s stoked by a deceptive bit of muckraking in the form of a documentary written and produced by Lea Thompson entitled DPT: Vaccine Roulette, which first aired on a local NBC affiliate in Washington DC on April 19, 1982, and then ultimately was aired nationally on The Today Show. The documentary linked the whole cell pertussis component of the DTwP to encephalopathy through a series of horrific anecdotes of children who developed severe neurological issues after the DTP. Later, Harris Coulter and Barbara Loe Fisher (yes, that Barbara Loe Fisher, who also around the same time founded the antivaccine group the National Vaccine Information Center) wrote a book, DPT: A Shot in the Dark, further inflamed fears about the DPT vaccine being linked to encephalopathy that later studies failed to confirm, as Steve Novella described. So, in essence, a highly effective vaccine was traded in for a vaccine that’s also effective, but doesn’t provide immunity that is as long lasting, all because of fears of reactions that turned out not to be a risk of the original whole cell pertussis vaccine. To be fair, it’s clear that the DTwP caused more fevers and other side effects, but current evidence doesn’t support the link between the DTwP and really severe neurological complications, such as encephalopathy.

Finally, there’s this:

Finally, we should consider the potential contribution of genetic changes in circulating strains of B. pertussis.4 It is clear that genetic changes have occurred over time in three B. pertussis antigens — pertussis toxin, pertactin, and fimbriae. In fact, changes in fimbrial agglutinogens related to vaccine use were noted about 50 years ago. Studies in the Netherlands and Australia have suggested that genetic changes have led to vaccine failures, but many people question these findings. If genetic changes had increased the rates of vaccine failure, one would expect to see those effects first in Denmark, which has for the past 15 years used a vaccine with a single pertussis antigen (pertussis toxin toxoid). To date, however, there is no evidence of increased vaccine failure in Denmark.

These are the observations behind the claims by cranks like Mercola that vaccines are “causing dangerous mutations.” While it is possible that the B. pertussis bacteria is developing “resistance” to the vaccine through natural selection, the evidence that it is doing so strikes me as rather weak and preliminary. Even if it were, the answer would be to change the vaccine in order to include the evolved antigens. After all, do we decide that antibiotics as a class of drugs don’t work when bacteria evolve resistance or that chemotherapy as a class of drugs doesn’t work when tumors manage to do the same? That’s a rhetorical question, of course. Some segments of the alt-med world do, indeed, do just that, but reasonable scientists and physicians do not. They work to overcome that resistance.

Leaving aside that hypothetical problem that might be contributing to pertussis epidemics in the era of the acellular vaccine, what can be done to bring these epidemics under control? First, Cherry notes that the purpose of vaccination against B. pertussis is not to eliminate all disease. It’s to prevent serious disease (whooping cough) with its potentially horrific complications, up to and including death, particularly among young infants. One possible approach to deal with the issue of waning immunity of the DTaP vaccine would be to start it at a younger age with shorter intervals between doses. Another strategy might be to immunize pregnant women in order to reduce the risk that the mother will acquire pertussis around the time of delivery, with the added bonus that it would give the infant some protection for a month or two through maternal antibodies.

The point of course is that these recent epidemics, while they point to problems with the current vaccination schedule, do not by any means demonstrate that the vaccine doesn’t work or that it’s failed. Commenting on the current pertussis outbreak in Washington, the CDC put it in a recent MMWR:

The ongoing pertussis epidemic in Washington reflects the evolving epidemiology of pertussis in the United States. Although acellular pertussis vaccines provide excellent short-term protection, early waning of immunity might be contributing to increasing population-level susceptibility. Nevertheless, vaccination continues to be the single most effective strategy to reduce morbidity and mortality caused by pertussis. Vaccination of pregnant women and contacts of infants is recommended to protect infants too young to be vaccinated. In light of the increased incidence of pertussis in Washington and elsewhere, efforts should focus on full implementation of DTaP and Tdap recommendations to prevent infection and protect infants.

I also have one final point. While the evidence that pockets of unvaccinated children are the nidus for measles outbreaks is compelling, these latest pertussis outbreaks do not appear to be correlated with pockets of unvaccinated children. Certainly, none of the studies I’ve cited indicate that unvaccinated children are a major cause of these outbreaks, although common sense suggests that the existence of pockets of unvaccinated children can’t be helping and is unlikely even to be neutral. Unvaccinated children are, after all, at a 23-fold increased risk of catching whooping cough, which allows for the degradation of herd immunity at the very least as well as providing a reservoir for the offending bug, and the first two studies I discussed indicate that for most age ranges unvaccinated and undervaccinated children are at a significantly increased risk of catching pertussis than fully vaccinated children; the problem is primarily at one age range where waning immunity from the DTaP leaves a gap in immunity. However, in this case, as far as I’ve been able to tell, unvaccinated children do not appear to be the primary drivers of these most recent pertussis epidemics, as they are for measles outbreaks. We as science-based supporters of vaccination have to be careful not to overstate our case and blame antivaccinationists for these pertussis epidemics without adequate evidence. That only provides antivaccinationists ammunition to use against science-based vaccine policies.

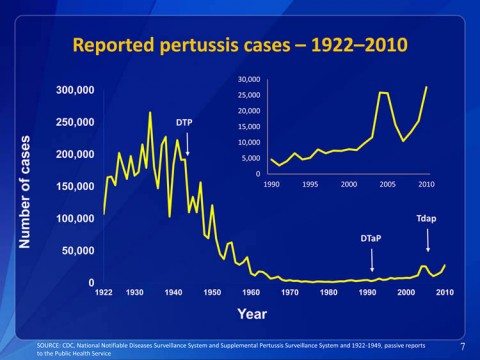

It would be nice if antivaccinationists would do the same and not overstate their case. It would be even nicer if they wouldn’t use outright misinformation to argue their case. Of course, if they were to do so, then they wouldn’t be antivaccinationists anymore. The difference between science-based supporters of vaccination and antivaccinationists is simple. We face reality. Evidence and science matter to us. When vaccines do not function as well as we would like and try to fix it. Even with the problems with waning immunity due to acellular pertussis vaccine and even with these recent epidemics of pertussis, as Cherry reminds us, today’s incidence of pertussis is still about one twenty-third of what it was during a typical epidemic year in the 1930s. Don’t believe me? Then take a look at this presentation by Thomas Clark, MD, MPH about pertussis epidemiology and vaccination. This slide set includes a slide that puts the graph above from Cherry’s paper into proper context:

That rather puts the antivaccinationists’ attacks on the acellular pertussis vaccine into perspective, doesn’t it? Indeed, I can’t help but note that the graph above shows the total number of cases. Because the U.S. population has grown considerably over the last 90 years, if it were graphed by incidence, the effect of the vaccine would likely be even more striking. In any case, this graph illustrates quite clearly that the pertussis epidemics over the last few years are mere blips on the curve compared to what was observed in the past, before there was a vaccine available to combat pertussis. In other words, even with the recent epidemics in the US, this is not the bad old days, when up to 270,000 cases of pertussis could be diagnosed in a year, with as many as 10,000 deaths, mostly among infants. Still, although this is good, it is not nearly good enough. We can do better. Contrary to what antivaccinationists tell us, recent outbreaks of pertussis do not mean that vaccines don’t work. They do, however, mean that we probably need to develop a new vaccine that overcomes the shortcomings of the existing DTaP. In the meantime, it also suggests that we need to use the vaccine we have better, perhaps through earlier and more frequent doses, until we have a new vaccine.