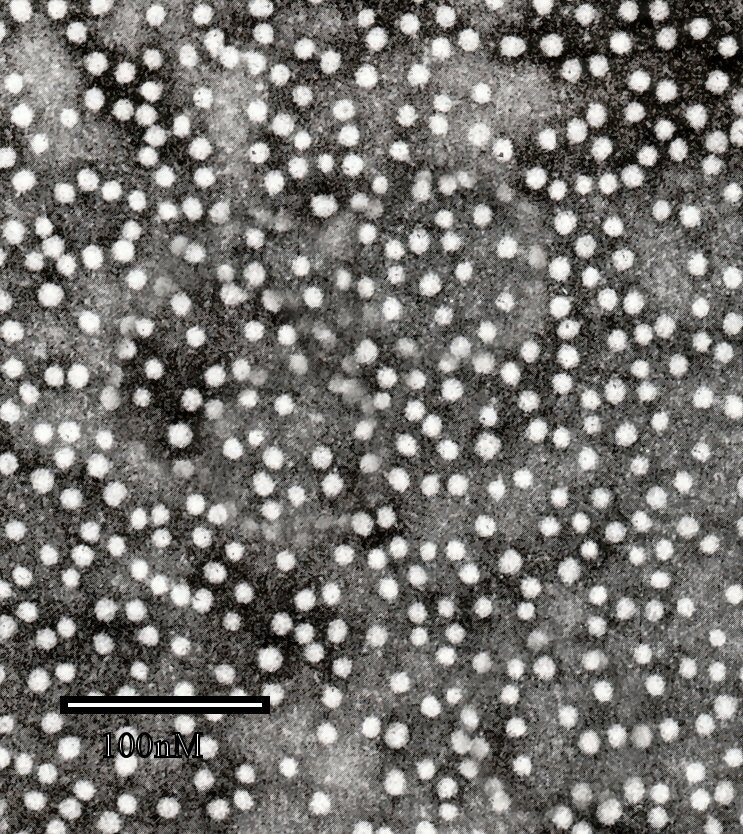

Hepatitis B virus surface antigens

I am just a parent with some questions about vaccine safety and was happy to find your website. I have noticed that the Scandinavian countries do not routinely recommend HepB vaccination unless the mother is a known carrier. I did not see this addressed anywhere on your website and I hope you or one of your colleagues might consider discussing the reasons that some advanced countries are not routinely giving this particular vaccine. Thank you.”

Vaccination is a complicated and at times confusing topic that generates a large number of quite reasonable questions by parents like the one above. At the same time, the ever-wandering aim of the anti-vaccinationist movement appears once again to be falling on the vaccine against Hepatitis B, and I’ve heard them pose this very question with the intent of sowing doubt in the current vaccination schedule. Regardless of the source, this question is clearly on the mind of some parents, and I am happy to answer it.

As usual, this question has quite a bit to parse out. I think it may be most helpful to examine why we vaccinate against Hepatitis B the way we do in the US, how most countries in the world approach the problem, and finally examine the reason why eight European countries do not universally vaccinate against HBV. First things first though: what is Hepatitis B?

Hepatitis B

Hepatitis B (HBV) is a double stranded DNA virus found in the bodily fluids of infected people including their blood, semen, and saliva, and can be transmitted through sexual contact, exposure of infected fluid to mucous membranes, or through injection.

As the name suggests, infection causes damage primarily to the liver, though the spectrum of disease experienced by any one person can be quite broad. In adults, 50-70% of infections are asymptomatic or mild enough to not come to medical attention. The remaining adults experience a range of hepatitis lasting weeks to months, with ~1% of these being a fulminant, life-threatening infection. Adults are relatively efficient in their ability to clear the virus after the initial infection, and only ~10% become chronicly infected carriers.

Children, on the other hand, present a very different pattern of disease. Though ~90% of infected children are initially asymptomatic, they are rarely able to clear the virus. 90% of infants and 25-50% of those 1-5 years old will become lifelong carriers.

Chronic Hepatitis B infection is a serious problem. Beyond the ability of most chronic carriers to spread the virus throughout their lives, ~ 20% of people with chronic Hepatitis B develop cirrhosis, a condition where the liver cells are lost and the liver becomes progressively more fibrotic and dysfunctional.

Cirrhosis isn’t the only life-limiting problem to result directly from chronic Hepatitis B infection. Hepatocellular carcinoma, a primary cancer of the liver, is in the top 10 cancers in both sexes in the US, and 60-80% of all cases are cause by Hepatitis B. All told, around 25 % of people who become chronically infected with Hepatitis B will die from its complications.

Hepatitis B is a major cause of worldwide morbidity and mortality. More than 1/3 of the world’s population has been infected with Hepatitis B and 5% are chronic carriers. That totals up to around 350,000,000 people chronically infected, and around 620,000 deaths from HBV yearly.

As in many health care related issues, the worldwide epidemiology of HBV infection does not necessarily reflect that of the United States. Even so, the picture isn’t particularly pretty. Around 5% of the US population has been infected with Hepatitis B, and 0.3 are chronic carriers. Most HBV infections occur in those aged 25-44 (4/100,000), with the lowest rates of infection in those under 15 (0.1/100,000). In 2007 4,519 new cases in the US were reported to the CDC, though this represents a fraction of the total number of infections.

These numbers are significant. To put this in perspective, the mortality from HBV in the US was 5 times higher than Haemophilus influenza type B and 10 times greater than measles before vaccination was introduced.

The hepatitis B vaccine

HBV is a relatively stable virus posing a serious public health threat with humans as the only known reservoir, and as such is a prime target for prevention, and theoretically eradication, through vaccination. The first vaccine against HBV became available in 1981, and the current recombinant vaccine has been in use since 1986. As a recombinant vaccine it contains proteins normally made by HBV, but does not have the virus itself, and therefore carries no risk of HBV infection.

As far as efficacy is concerned, the HBV vaccine has a very high response rate, inducing an appropriate antibody response in more than 95% of people from birth to 30 years of age, and decreasing but still significant response rates in older age groups. Immunity from the vaccine lasts at least 20 years in healthy individuals.

The HBV vaccine has an excellent safety record. The most common side effects are pain and swelling at the injection site in ~3% of people, and fever in ~1%. The only serious confirmed reaction is anaphylaxis that occurs in 1/600,000 injections with no deaths reported in over 20 years of use. Concerns regarding the HBV vaccine’s association with demyelinating diseases, the use of thimerosal in its formulation in the past or aluminum at the present have all been investigated and found to be without support; I will give such allegations no further time in this post.

Strategies of hepatitis B vaccine use

There are a number of viable strategies available to countries seeking to address the spread of HBV in their populations, and variants on each. When deciding which strategy is best for any given country, there are multiple factors to consider, including disease severity, the availability and efficacy of treatments, the risk and cost of infection, the risk, efficacy and cost of vaccination, etc.

The first option is to vaccinate people at high risk of infection. In situations where the risk of infection is very low this makes good sense. For instance, in the US the risk of contracting Yellow Fever is essentially zero at baseline without vaccination. No risk or cost of vaccination, no matter how small, is small enough to offset zero risk of disease, therefore we do not routinely vaccinate against it. However, if you were to travel to an area where Yellow Fever is endemic, your personal risk can suddenly become significant, and easily justify the minimal cost and risk of vaccinating you as a person at high risk.

Since the majority of people infected with HBV have identifiable risk factors, this approach makes some sense. However, it has several major drawbacks. It requires all individuals in a high-risk group to have health care, be identified, and to acquire the vaccine before they are infected. This is labor and cost intensive, and extremely unlikely to capture the entire target population. Well executed, this approach can protect a majority of people at high risk, but in the case of HBV it will not immunize a large enough population to generate a herd immunity effect. The greatest flaw of this approach lies in the 1/3 of HBV infections that occur in people with zero known risk factors who, by definition, are unable to further reduce their risk, and are left unprotected by a vaccine. These shortcomings guarantee this strategy will fail to fully control the spread of HBV in the community.

The second approach is to vaccinate the entire population as they enter into the age of greatest incidence of infection, adolescence and early adulthood. This addresses one of the shortcomings of the first strategy, namely the need to identify people at high risk. It also takes advantage of the fact that children more reliably have health-maintenance office visits than do adults, and are more likely to be given vaccinations as part of a universal schedule.

Though this captures a large majority of the total number of infections, it too has a flaw; it fails to address the people infected in early childhood. Though this is a relatively small number of people (4% of HBV infections), remember that children are far more likely to become lifelong carriers, and thus make up a disproportionate number of the infected at any one point in time (24% of chronic carriers). While more effective at reducing the prevalence of HBV in the population than only vaccinating high-risk groups, this strategy too has little hope of eliminating HBV.

The third possible strategy is to vaccinate people at the time of birth. This strategy addresses the problem of perinatal infection, prevents the acquisition of HBV by people during early childhood when the risk of chronic infection is highest, and since the immunity it induces lasts for decades it covers the entire population during the highest risk times of their lives. Universal vaccination with HepB vaccine at birth, even in regions with a low prevalence of chronic carriers like the US, could reduce mortality by an additional 10-20% compared to early childhood vaccination.

Even this strategy has a drawback, however, and that is time. Beginning an immunization program with only infants would take a few decades to generate a maximum reduction in HBV in the population.

The US vaccination strategy

Though the burden of disease from HBV in the US is relatively low compared to say, heart disease, it remains a significant public health threat only partially addressed through screening, education, and preventative measures, and with limited treatment options. This makes it an ideal target for vaccination.

From 1981 through 1991 the US vaccinated only people with identified risk factors. Predictably, this campaign had an underwhelming effect on HBV infections seen during this time period.

In 1991, the strategy was reworked to better address the various methods of HBV transmission in an attempt to eliminate HBV spread in the US. The new strategy is an amalgam of all three strategies described earlier. In addition to vaccination of high risk groups, we began universal vaccination of all infants at birth, vaccination of adolescents, and prenatal screening of pregnant women to identify children who would require not only vaccination at birth but also Hep B immunoglobulin (HBIG).

Since its launch in 1991, we have seen a steady decrease in Hepatitis B infections. Hep B incidence in the US fell from 10.7/100,000 in 1983 to 2.1 per 100,000 in 2004. (25,916 total cases down to 6212 cases). Though it’s true other factors have been contributing to HBV’s decline, most notably the public education campaign aimed at curbing the spread of HIV, this doesn’t account for the pattern of HBV decline across age groups. There has been a 95% drop in HBV in people under 15 years of age, 87% in ages 15-24, 71% from 25-44, and 51% decrease in people over 45 years old. This is precisely what you would expect from a pediatric vaccination campaign.

Using a cost effective and exceptionally low-risk intervention of universal Hep B vaccination the US is well on its way to control, if not elimination, of HBV.

The northern European vaccination strategy

The strategy taken by the US is typical of most developed nations, even those with a relatively low incidence of HBV. In 1992 the WHO recommended the inclusion of HBV vaccination in nearly all national vaccination programs. Since that time, the vast majority of countries (177/193 countries) have adopted infant HBV vaccination into their childhood schedules as can be seen here. This graphic also illustrates the few countries that have instead opted to vaccinate only high-risk individuals, primarily those in Northern Europe, including Scandinavia.

The reason these countries have not adopted universal vaccination against HBV is the exceptionally low level of HBV in their population and the associated costs of prevention. Sweden, for instance, has one of the lowest prevalences of HBV in the world at 0.05%. This is 6 times lower than what we have in the US, with the majority of cases occurring in those engaged in high-risk activities or in immigrant populations that tend to have minimal contact with the indigenous population. The public health organizations of these Northern European countries consider HBV to be a minor public health problem best addressed by targeted vaccination. The cost of instituting universal vaccination would not offset the benefit of further reduction in HBV prevalence in their countries.

It is interesting to note that though these countries have low baseline rates of HBV infection, they have not generated the same relative decrease in rates that countries, like the US, have been able to produce with universal HBV vaccination. This fact, in combination with high immigration rates to these countries from areas of heavy HBV, makes it likely that the cost/benefit ratios of the Northern European countries will sway even more strongly in favor of universal HBV vaccination over the next several years.

It is also worth noting that of the many factors being weighed by the medical community and public health officials of these Northern European nations, serious concerns of the Hepatitis B vaccine’s efficacy or safety are not among them.

Conclusion

We will continue to make progress in medicine by never being satisfied the care we provide is good enough; the ongoing debate about how best to apply the Hepatitis B vaccine is an excellent example of this concept. The inconsistency between these nations’ vaccination policies is little more than physicians and health care officials seeking the most efficient and effective use of the vaccine within the unique conditions inside their borders.