The Cultural Revolution

After investigating ‘acupuncture anesthesia’ in the People’s Republic of China in 1973, John Bonica wrote:

From the guarded comments made by several anesthesiologists, I concluded that this disuse [of ‘acupuncture anesthesia,’ after its introduction in 1958 until the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution began in 1966] was the result of disappointing failures in a significant proportion of patients. During the Cultural Revolution this “negative” trend of not using acupuncture was considered the work of revisionists, and subsequently greater emphasis was given to the widespread use of acupuncture in all hospitals.

Similarly, according to Petr Skrabanek,

Those who dared ask such awkward questions [about ‘acupuncture anesthesia’] were branded as “counter-revolutionary revisionists.”

Skrabanek’s reference for that assertion was this 37-page pamphlet:

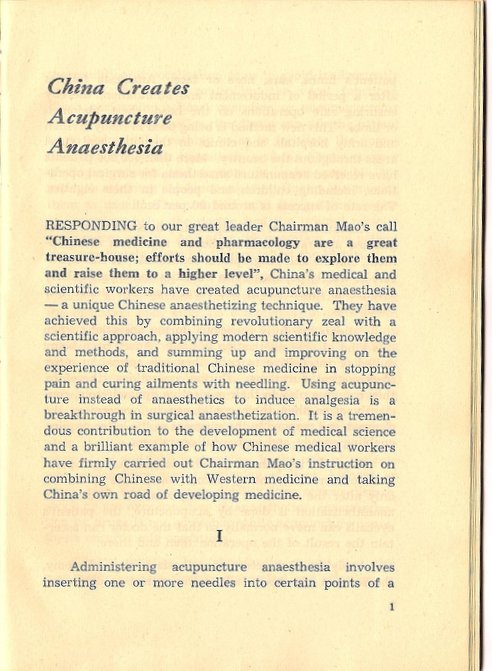

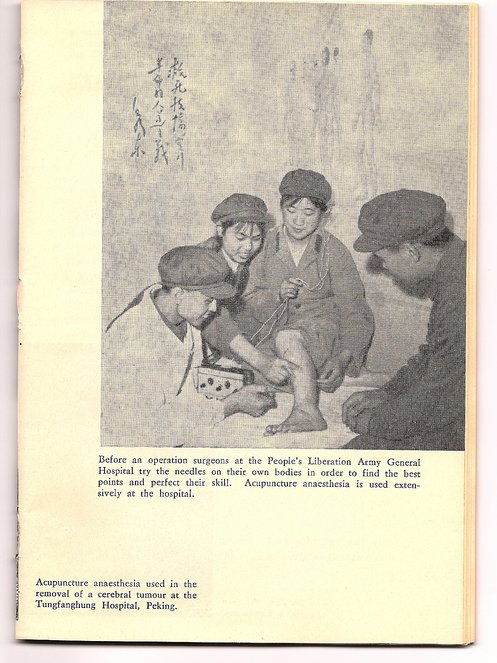

It had been published by the Beijing Foreign Languages Press in 1972, smack in the middle of the Cultural Revolution and only one year after James Reston’s trip to China. It is the epitome of ‘revolutionary’ literature, as these excerpts and photos attest:

The text is filled with extravagant claims for the success and widespread use of acupuncture anesthesia, which we know from Dr. Bonica’s reports are untrue. From Kim Taylor we learned that the ‘science’ underpinning the new TCM is not science in the usual sense, and this pamphlet bears that out. Dialectical materialism and Chairman Mao (who is praised on nearly every page) are credited with providing not only the motivation, but the conceptual basis for the practice:

During the Great Cultural Revolution, medical workers at the P.L.A. Kwangchow Units Central Hospital, the Peking Tuberculosis Research Institute, the No. 1 Tuberculosis Central Hospital in Shanghai and other hospitals conscientiously studied Chairman Mao’s philosophical works to guide their practice. Boldly experimenting on themselves with needles to determine the degree of pain, they eliminated the unnecessary points and, by grasping the main contradiction and bringing into play the role of the main points, succeeded in reducing the needles to a few and sometimes even to one…

Chinese medical and scientific workers are making still greater efforts in studying Marxism-Leninism-Mao Tsetung Thought and are using dialectical materialism to guide their medical work and scientific research. Daring in practice and in breaking new ground, they are bending their efforts to perfect acupuncture anesthesia.

The pamphlet also makes extravagant claims for other uses of acupuncture:

Chinese medical workers have in the last few years discovered many new points and cured many ‘incurable’ diseases. Deep needling of the yamen point, for instance, enables deaf-mutes to hear and speak, and in some cases of infantile paralysis or paraplegia, suitable stimuli from needling certain points can, after a period of treatment, restore the functions of limbs paralysed for years.

Skrabanek’s assertion about “awkward questions” must have been based on this passage (emphasis in the original):

‘New things always have to experience difficulties and setbacks as they grow.‘

No sooner had acupuncture anaesthesia appeared than it was suppressed by Liu Shao-chi‘s counter-revolutionary revisionist line and attacked by bourgeois ‘experts.’ In a vain attempt to nip it in the bud, they raved that it was ‘not scientific,’ ‘without any practical value,’ and a ‘retrogression’ in the history of anaesthesia.

Repeatedly studying Chairman Mao’s teaching ‘We cannot just take the beaten track traversed by other countries in the development of technology and trail behind them at a snail’s pace,’ the medical workers made up their minds to break new ground for anesthesiology. Disregarding ridicule and attacks, they persisted in accumulating experience through clinical practice and constantly raising the efficacy and widening the scope of applying acupuncture anaesthesia in operations.

The Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution swept away the bourgeois trash, and revolutionary medical workers relentlessly criticized Liu Shao-chi’s counter-revolutionary revisionist line in health work and scientific research. This facilitated great development and improvement in acupuncture anaesthesia.

Conclusion: Seeking Truth from Facts

In Part I of this series we saw that in many of the operations witnessed by Westerners in the 1970s, ‘acupuncture anesthesia’ had been supplemented with sedatives, narcotics, and local anesthetics. We also saw that some people seem surpisingly tolerant of surgical procedures performed without anesthesia, and that during the 19th century Western surgeons had been particularly impressed by that capacity in Chinese patients. In Part II we saw abundant, albeit indirect evidence that many patients undergoing surgery with ‘acupuncture anesthesia’ in China during the early 1970s felt substantial pain, but upon questioning denied it. Part II ended with this question:

“Rather than being an important Chinese achievement, was ‘acupuncture anesthesia’ more a form of torture perpetrated by a totalitarian government on its own citizens, with the forced complicity of physicians?”

Historian Paul Unschuld, considering the time of Nixon’s visit to China, observed in 1997:

Attempts to use needles instead of drugs to achieve anesthesia even in major surgical operations have in the meantime slipped into deserved oblivion, just as much as collective management and public self-criticism. It was not until after the ‘Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution’ in 1976 and the opening of China in 1978 that Chinese doctors were able to report, without personal risk, about the pain that patients had been expected to endure through therapy applied in operating theaters not on the basis of scientific knowledge, but in accordance with the ideological precepts of the Communist Party.

Readers who are familiar with the origin of the People’s Republic of China or who have read Part III of this series will recognize the subtitle of this section as a quotation from Chairman Mao. It was also part of the title of an essay written in 1980 by two of the doctors referred to by Paul Unschuld: Keng Hsi-chen and T’ao Nai-huang. An English translation of their essay is printed in another of Unschuld’s books and is intermittently available almost in its entirety here, beginning on p. 360. Here are the essential excerpts:

The pushing of acupuncture anesthesia into large areas of clinical application cannot be separated from the peculiar historical conditions in our country of that time. During the period of the ‘Cultural Revolution,’ acupuncture anesthesia served politically as a standard to judge progress or backwardness, revolution or nonrevolution. Physicians and patients were under the pressure of the political requirements of that time. They had no choice but to have exceptional courage in order to carry out or undergo surgery, especially as the patients who felt pain could not cry out. Some resorted to shouting political slogans during surgery in a loud voice. At one place, the chairman of ophthalmology was enthusiastic about acupuncture anesthesia, and he tried the knife at his own eyelid. Finally he reached the conclusion: the effects are not good, it should not be extended. He wrote a report to higher authorities and as a result he was labeled one with three hats [i.e., an intellectual not interested in practice] and met the criticism of the masses. Under this type of political pressure, not a few people made statements against their will and acted against their conscience. Thus, in some hospitals the rate of acupuncture anesthesia utilization reached 20 percent, but among these, 80 percent were ligation operations. In other hospitals before clinical application of acupuncture anesthesia, the patients were given already sufficient amounts of anesthetic drugs through injection and then, in addition, needles were pierced into their ears pretending acupuncture anesthesia. Only joy was reported but no sorrow; one did not dare to tell the facts. This of course had decisive influence on how the concerned leadership department passed correct decisions regarding the real situation of acupuncture anesthesia.

…

Our opinions expressed here are not taken out of thin air. We, the authors, have in the past, from 1969 through 1977, as part of our work in the hospital, conducted more than thirty thousand surgical operations under acupuncture anesthesia as an exploratory practice in order to warmheartedly promote acupuncture anesthesia. This represents about 1.5% of all cases of surgery under acupuncture anesthesia in our country. This tremendous amount of practice has led us to publish the opinions offered above. Also, these opinions are not really our own original ideas, they are extensively discussed and acknowledged among medical personnel of anesthetics and surgery. It is just that due to the political pressure of the past period, nobody dared to state them openly.

The answer to the question, then, is clear. Most Westerners—Michael DeBakey, John Bonica, and Arthur Taub being exceptions—who observed ‘acupuncture anesthesia’ in China during the Cultural Revolution seem to have failed to recognize what was going on right under their noses. No surprise, then, that many Westerners continued to have an insatiable appetite for the exotic ‘healing’ wares of the Mysterious Orient, and even post-Mao China has been only too willing to accomodate them.

Epilogue: if not Anesthesia, is there Acupuncture Analgesia?

A few years after his trip to China, John Bonica reported his experience using acupuncture to treat patients in his pain clinic:

At the University of Washington Pain Clinic, a self-selected series of 100 patients suffering from chronic pain refractory to other forms of conventional therapy undertook a trial of acupuncture analgesia at weekly intervals. Although the initial results were often spectacularly successful, following the third treatment, long-term benefit from acupuncture analgesia was as disappointing as other forms of therapy for this intractable group of patients. None of the 100 patients showed any continued objective evidence of pain relief, ie, medication intake and functional impairment continued despite claimed subjective relief in a small percentage of the patients. Only three out of the hundred patients claimed long-term (upwards of three months) pain relief from a course of acupuncture at approximately weekly intervals, but they did not, as a result of this claimed relief, decrease analgesic medicines or improve their activity levels.

Similar patterns of response to acupuncture therapy for chronic pain states have been noted by other investigators. In a well-controlled clinical trial, Lee and associates demonstrated that it did not matter if the needles were inserted in traditional meridian points or in “control” points. The results were similar: temporary relief. Only 18% of their 261 patients obtained good relief (15%) beyond four weeks after a series of four acupuncture treatments…

Funny: such findings are remarkably similar to those that continue to be reported more than 30 years later. Is that telling us something?

***

The ‘Acupuncture Anesthesia’ series:

1. “Acupuncture Anesthesia”: A Proclamation from Chairman Mao (Part I)

2. “Acupuncture Anesthesia”: A Proclamation from Chairman Mao (Part II)

3. “Acupuncture Anesthesia”: A Proclamation from Chairman Mao (Part III)

4. “Acupuncture Anesthesia”: A Proclamation from Chairman Mao (Part IV)

5. ‘Acupuncture Anesthesia’ Redux: another Skeptic and an Unfortunate Misportrayal at the NCCAM