If there’s one thing we emphasize here on the Science-Based Medicine blog, it’s that the best medical care is based on science. In other words, we are far more for science-based medicine, than we are against against so-called “complementary and alternative medicine” (CAM). My perspective on the issue is that treatments not based on science need to be either subjected to scientific scrutiny if they have sufficient prior plausibility or strong clinical data suggesting efficacy or abandoned if they do not.

If there’s one thing we emphasize here on the Science-Based Medicine blog, it’s that the best medical care is based on science. In other words, we are far more for science-based medicine, than we are against against so-called “complementary and alternative medicine” (CAM). My perspective on the issue is that treatments not based on science need to be either subjected to scientific scrutiny if they have sufficient prior plausibility or strong clinical data suggesting efficacy or abandoned if they do not.

Unfortunately, even though the proportion of medical therapies not based on science is far lower than CAM advocates would like you to believe, there are still more treatments in “conventional” medicine that are insufficiently based on science or that have never been validated by proper randomized clinical trials than we as practitioners of science-based medicine would like. This is true for some because there are simply too few patients with a given disease; i.e., the disease is rare. Indeed, for some diseases, there will never be a definitive trial because they are just too uncommon. For others, it’s because of what I like to call medical fads, whereby a treatment appears effective anecdotally or in small uncontrolled trials and, due to the bandwagon effect, becomes widely adopted. Sometimes there is a financial incentive for such treatments to persist; sometimes it’s habit. Indeed, there’s an old saying that, for a treatment truly to disappear, the older generation of physicians has to retire or die off.

That is why I consider it worthwhile to write about a treatment that appears to be on the way to disappearing. At least, I hope that’s what’s going on. It’s also a cautionary tale about how the very same sorts of factors, such as placebo effects, reliance on anecdotal evidence, and regression to the mean, can bedevil those of us dedicated to SBM just as much as it does the investigation of CAM. It should serve as a warning to those of us who might feel a bit too smug about just how dedicated to SBM modern medicine is. Given that the technique in question is an invasive (although not a surgical technique), I also feel that it is my duty as the resident surgeon on SBM to tackle this topic. On the other hand, this case also demonstrates how SBM is, like the science upon which it is based, self-correcting. The question is: What will physicians do with the most recent information from very recently reported clinical trials that clearly show a very favored and lucrative treatment does not work better than a placebo?

Here’s the story that illustrates these issues, fresh from the New York Times this week:

Two new studies cast serious doubt on a widely used and expensive treatment for painful fractures in the spine.

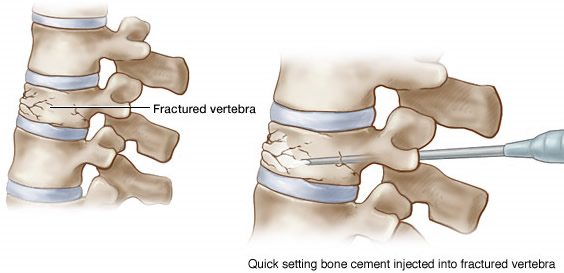

The treatment, vertebroplasty, injects an acrylic cement into bones in the spinal column to ease the pain from cracks caused by osteoporosis, the bone-thinning disorder common in older people. Doctors began performing it in this country in the 1990s, patients swore by it — some reporting immediate relief from terrible pain — and it soon caught on, without any rigorous trials to determine whether it really worked.

The new studies are exactly the kind of research that health policy experts and President Obama have been calling for, to find out if the nation is spending its health care dollars wisely, on treatments that work. A bill passed by Congress this year provides $1.1 billion for such so-called comparative effectiveness research.

The studies of vertebroplasty, being published Thursday in The New England Journal of Medicine, found it no better than a placebo. But it remains to be seen whether the findings will change medical practice, because they defy the common wisdom and challenge a popular treatment that many patients and doctors consider the only hope for a very painful condition.

These are the two studies in question, and they were published in last week’s New England Journal of Medicine. Whenever a journal as prestigious and widely read as the NEJM publishes two studies of the same clinical question in the same issue, as companion studies, it’s trying to send a message. This time, the message is loud and clear:

- Kallmes DF, Comstock BA, Heagerty PJ, Turner JA, Wilson DJ, Diamond TH, Edwards R, Gray LA, Stout L, Owen S, Hollingworth W, Ghdoke B, Annesley-Williams DJ, Ralston SH, Jarvik JG (2009). A randomized trial of vertebroplasty for osteoporotic spinal fractures. New Engl. J. Med. 361:569-579.

- Buchbinder R, Osborne RH, Ebeling PR, Wark JD, Mitchell P, Wriedt C, Graves S, Staples MP, Murphy B (2009). A randomized trial of vertebroplasty for painful osteoporotic vertebral fractures. New Engl. J. Med. 361:557-568.

Before I get into the meat of the studies, let’s take a look at what vertebroplasty is. Vertebral fractures in patients with osteoporosis represent a very difficult problem to deal with. The reason is that they can be extremely painful and, worse, very difficult to get to heal using conventional methods. Indeed, the pain can be so severe that powerful narcotics are the only thing that can control it. Given that it can sometimes take months for such fractures to heal (if they heal at all), “conservative” treatment is not very satisfactory. Not surprisingly, a search for treatments that could decrease the disability, pain, and even death from these fractures was imperative. Years ago, a procedure known as percutaneous vertebroplasty, which involved the injection of polymethylmethacrylate directly into the vertebral compression fracture under the guidance of fluoroscopy, was first reported. Initial anecdotal reports suggested a very rapid and effective relief of pain after the procedure. The other aspect of vertebroplasty that led physicians to believe that it could work to relieve pain from compression fractures is that the technique had some degree of prior plausibility. The concept was that the injection of cement into the fracture would provide rapid stabilization of the fracture and therefore rapid relief of pain. It’s never been proven that that is the mechanism, but, according to the principles of prior plausibility, there was at least a reasonable hypothesis as to how vertebroplasty might stabilize fractures and relieve pain.

Now let’s take a look at the introduction of Buchbinder et al:

Observational studies suggest that there is an immediate and sustained reduction in pain after this procedure is performed,5 but data from high-quality randomized, controlled trials are lacking. The best currently available evidence for the efficacy of vertebroplasty comes from one randomized, open trial involving 34 patients and two quasi-experimental, open, controlled, before–after studies that compared vertebroplasty with conservative treatment. Although each study showed an early benefit of vertebroplasty, methodologic weaknesses cast doubt on the findings. In particular, the lack of blinding and the lack of a true sham control raise concern that the observed benefits reflected a placebo response, an effect that may be magnified with an invasive procedure.

Does this sound familiar? For long-time readers of SBM, it should. I’ve written about it before, as have others, in two contexts. First, consider acupuncture. Time and time again, we have pointed out how acupuncture studies tend to be positive for early, smaller, less rigorously controlled studies but in larger and better-controlled studies the observed treatment effect disappears. This sort of progression is very typical for interventions that don’t produce an effect that is measurably greater than that of a placebo. And it is this sort of progression that appears to have occurred for vertebroplasty. Indeed, look at this New York Times article from four years ago:

No one is sure why it helps, or even if it does. The hot cement may be shoring up the spine or merely destroying the nerve endings that transmit pain. Or the procedure may simply have a placebo effect.

And some research hints that the procedure may be harmful in the long run, because when one vertebra is shored up, adjacent ones may be more likely to break.

But vertebroplasty and a similar procedure, kyphoplasty, are fast becoming the treatments of choice for patients with bones so weak their vertebrae break.

The two procedures are so common, said Dr. Ethel Siris, an osteoporosis researcher at Columbia University, that “if you have osteoporosis and come into an emergency room with back pain from a fractured vertebra, you are unlikely to leave without it.” She said she was concerned about the procedures’ widespread and largely uncritical acceptance.

Sound familiar? If not, consider this quote:

“I struggle with this,” said Dr. Joshua A. Hirsch, director of interventional neuroradiology at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston. He believes in clinical trials, he said, but when it comes to vertebroplasty and kyphoplasty, “I truly believe these procedures work.”

“I adore my patients,” Dr. Hirsch added, “and it hurts me that they suffer, to the point that I come in on my days off to do these procedures.”

Again does this sound familiar? How many times have we heard the same sorts of quotes from CAM practitioners? Dr. Hirsch apparently started with the noblest of motives, wanting to relieve his patients’ unremitting pain from spinal metastases due to cancer or fractures due to osteoporosis. He still believed in 2005 that he was helping; otherwise he would probably have abandoned vertebroplasty. Many CAM practitioners start out similarly, no doubt. They come up with a method or a treatment, see what appears to be a good result, become convinced that it works, and thus become true believers. The difference is that, as an academician Dr. Hirsch at least felt uneasy about advocating this therapy without adequate research or strong objective evidence to show that it really works better than a sham procedure, because doing so goes against his academic training. Nonetheless, Dr. Hirsch convinced himself by personal observation and small pilot studies that the procedure works, even though before the studies I’m about to discuss the evidence supporting vertebroplasty was actually very similar to the state of evidence for acupuncture in that the best evidence for the efficacy of vertebroplasty were two unblinded trials comparing vertebroplasty with medical management. Not surprisingly, they were positive trials showing a benefit for vertebroplasty over medical management. That the the Director of Interventional Neuroradiology at Massachusetts General Hospital could convince himself that an unproven treatment works on the basis of personal observation and small pilot studies simply shows how easy it is to persuade oneself to believe what one wants to believe, no matter how scientific one views oneself.

Then comes hard, cold science.

First up is a multi-institutional study (Kallmer et al) involving five centers in the United States, five centers in the United Kingdom, and one center in Australia, led by David F. Kallmes, M.D. at the Mayo Clinic and Jeffrey G. Jarvik, M.D., M.P.H. at the University of Washington. According to the methods, “sites were selected on the basis of having an established vertebroplasty practice for osteoporotic fractures, an enthusiastic local principal investigator, and an available research coordinator.” The study was designed as a randomized, controlled, study, in which the experimental group underwent standard vertebroplasty, while the control group underwent a sham procedure in which local anaesthesia was infused, and verbal and physical cues, such as pressure on the patient’s back, were given. To complete the sham, the methacrylate monomer normally used to make up the glue was opened to simulate the odor associated with mixing of the cement. However, the vertebroplasty needle, the needle was not placed and the cement was not infused into the frature. Patients with fractures due to bone metastases, bleeding disorders, and a few other criteria were excluded. Overall it was a sound design, but the investigators had trouble recruiting patients to the trial. Indeed, the NYT article from 2005 describes just this for Dr. Jarvik’s trial:

In 2002, a group of researchers received a federal grant for a clinical trial that would be the first to rigorously assess vertebroplasty. But their study is faltering.

Patients in severe pain have proved unwilling to enter such a trial, in which they might be randomly assigned to get a placebo, and their doctors have been reluctant to suggest it. In 18 months, the investigators have been able to persuade just three medical centers to recruit patients, and only three patients have enrolled.

Now the investigators are looking for centers overseas, but they agree that the study’s prospects are dim and that its failure would leave critical questions unanswered.

“Whose responsibility is it to decide that something should be part of medical practice without adequate evidence that it works?” asked Dr. Jeffrey G. Jarvik, an investigator with the study and a neuroradiologist at the University of Washington.

Whose indeed? Once a belief has taken hold that a procedure works, it’s sometimes hard to persuade patients and physicians that a randomized study is ethical. Imagine how hard a sell this study would be to a patient at the apogee of pain from a compression fracture. That’s why there was a crossover design, in which patients, after one month, were allowed to crossover to the other group if they did not have adequate pain relief at one month.

In any case, this study was a resoundingly negative study. There were 131 patients enrolled (68 vertebroplasties and 63 simulated procedures), and the two groups were well matched. Both groups noted immediate and comparable improvement in disability and pain scores immediately after the intervention. At one month, there was no statistically significant difference between the control and vertebroplasty groups. The only hint of a possible effect is that there was a trend towards a higher rate of clinically meaningful reduction in pain in the vertebroplasty group, although, quite frankly, this result strikes me as a bit of the old trick of looking at multiple outcomes, trying to find one that comes out statistically significant. Let’s put it this way. This study is about as “positive” as any of the acupuncture studies we’ve dissected.

The second study (Buchbinder et al) was performed in Australia by a group led by Rachelle Buchbinder, Ph.D. It, too, was a multi-institutional study, with a control group that underwent vertebroplasty. The sham procedure was slightly different for this group, and, in my opinion, more rigorous. They underwent the same procedures as those in the vertebroplasty group up to the insertion of the 13-gauge needle, and to simulate vertebroplasty the vertebral body was gently tapped. As was done for Kallmes et al, the cement was prepared so that its smell permeated the room. Unlike Kallmes et al, there was no crossover was permitted in the design of this study. A total of 78 patients were enrolled and 71 completed the 6-month follow-up.

Buchbinder et al reported results that were just as unimpressive as those reported by Kallmes et al. In fact, they were more so, so much so that I will quote the abstract:

Vertebroplasty did not result in a significant advantage in any measured outcome at any time point. There were significant reductions in overall pain in both study groups at each follow-up assessment.

Can you say “placebo”? Sure, I knew you could.

Like Dr. Jarvik, Dr. Buchbinder crunched the data, looking for any outcome that could be considered even trending towards positive. She found none. This was about as negative a study as you can imagine, even more negative than most studies of homeopathy and acupuncture. This study found zero evidence that vertebroplasty is anything more than an elaborate placebo. Like acupuncture and homeopathy, come to think of it, the only difference being that there was some degree of prior scientific plausibility. Prior plausibility made vertebroplasty worth studying; however, these two trials provide emphatic evidence that it does not work, so much so that it surprised the authors, even though the very reason that the study had been done was because of nagging doubts that reported results seemed too good to be true:

Kallmes did the study because he always though the results reported for vertebroplasty seemed too good to be true–everyone got good results no matter how much cement was injected or what technique was used. And the mechanism through which vertebroplasty provided pain relief was a bit of a mystery. He figured if vertebroplasty was as good as promised, it would be easy to prove. He never expected results as stone cold negative as they were.

This is, of course, quite true. If vertebroplasty worked so well, it shouldn’t have taken much of a randomized trial to show it. If there’s one principle in medicine and clinical trials, it’s that dramatic treatment effects are much easier to demonstrate than weak ones. If vertebroplasty was as potent a treatment as advertised, these two trials should have easily shown its benefits. They did not. Indeed, in last week’s NYT article, there were a couple of more revealing quotes from the lead authors of these two studies:

“I’m going to be the most reviled radiologist on the planet,” said Dr. David F. Kallmes, the first author of one of the studies and a professor of radiology at the Mayo Clinic.

And:

“It does not work,” said Dr. Rachelle Buchbinder, a rheumatologist and epidemiologist at Monash University in Melbourne, Australia, and the leader of the Australian team. Dr. Buchbinder does not perform vertebroplasty and would “absolutely not” recommend it to patients, she said.

Dr. Kallmes, who helped develop vertebroplasty and has been performing it for 15 years, said his team was “shocked at the results.”

Shock is understandable. As had been pointed out in both papers, vertebroplasty had become the standard of care for the treatment of vertebral compression fractures. Medicare and insurance companies had, on the basis of unblinded studies, begun to reimburse for the procedure. Dr. Burbacher put it well:

Despite evidence that is acknowledged to be inadequate as a basis for justifying reimbursement, public institutions have recommended reimbursement for vertebroplasty. A recent position statement from various American radiologic and neurologic surgical societies also recommended funding the procedure.6 These endorsements have resulted in a dramatic increase in the number of vertebroplasties performed. For example, an examination of aggregate fee-for-service data from U.S. Medicare enrollees for the period from 2001 through 2005 showed that the rate of vertebroplasties performed during that time almost doubled, from 45.0 to 86.8 per 100,000 enrollees.14 There are also reports of repeat procedures for unrelieved pain at previously treated vertebral levels16 and of the prophylactic use of vertebroplasty in normal vertebrae that were deemed to be at high risk for fracture.

Not only is the short-term efficacy of vertebroplasty unproven, but there are also several uncontrolled studies suggesting that vertebroplasty may increase the risk of subsequent vertebral fractures, particularly in vertebrae that are adjacent to treated levels, sometimes after cement has leaked into the adjacent disk; controlled studies have shown conflicting results.

In other words, there’s money to be made. A lot of money. Combine that with “personal anecdotal experience” that suggests to both patients and the physicians who do the procedure that vertebroplasty “works,” giving interventional radiologists the feeling that they’re “doing good while doing well,” and you can see why the procedure’s use has taken off.

But what about all the reports of dramatic pain relief from vertebroplasty? They’re testimonials, of course. I’m going to go back to the 2005 NYT article:

Dr. Jensen knows firsthand how powerful such stories can be. In the late 1990’s, when vertebroplasty was new and many doctors were looking askance at it, she gave a talk to a group of doctors in Chicago.

“I could tell by looking at the audience that no one believed me,” she said. When she finished, no one even asked questions.

Finally, a woman in back raised her hand. Her father, she told the group, had severe osteoporosis and had fractured a vertebra. The pain was so severe he needed morphine; that made him demented, landing him in a nursing home.

Then he had vertebroplasty. It had a real Lazarus effect, the woman said: the pain disappeared, the narcotics stopped, and her father could go home.

“That was all it took,” Dr. Jensen said. “Suddenly, people were asking questions. ‘How do we get started?'”

Even after these two studies, there are patients who will not be convinced, as demonstrated in last week’s NYT article:

One patient in the study, Jeanette Offenhauser, 88, said she was convinced that the cement had helped her severe back pain, even after hearing the results.

One thing that people often don’t realize and even physicians sometimes forget is that surgery and invasive procedures provide one of the most powerful placebo effects there is; so it is not surprising that a procedural intervention like vertebroplasty could appear effective at the anecdotal experience level. A lesson in history might be in order here. There was an operation that was popular in the late 1930s through the 1950s for treating angina due to coronary artery disease. It was called pericardial poudrage, and it involved opening the chest and sprinkling sterile talcum powder on the heart. The idea was that the inflammation would cause angiogenesis (the influx of blood vessels into the heart to revascularize it). We know today that the inflammatory reaction thus caused is far too minor to make up for the loss of blood flow from a major coronary artery. Still, patients reported marked improvement of their symptoms. It wasn’t until the 1950s that an actual randomized blinded trial (the patients could be blinded but the surgeons couldn’t) was performed. It found no difference between patients who had poudrage and those who just had their chests opened and closed. (Imagine trying to get that one through the IRB today.) In other words, poudrage was no different than sham surgery.

So it appears to be with vertebroplasty.

Even doctors are having a hard time accepting these results. Even Dr. Kallmes himself argues that patients who want the procedure should still be able to get it, but only under the auspices of a clinical trial. That’s not entirely unreasonable, but Dr. Burbacher disagrees and says that these studies should be enough to abandon vertebroplasty. In an accompanying editorial, Dr. James Weinstein of the Department of Orthopaedics, Dartmouth Medical School, argued:

President Barack Obama has called for more comparative-effectiveness research as part of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act. Although clinical trials are an integral part of such research, from a safety and effectiveness standpoint, data from clinical trials combined with those from registries or other large longitudinal databases are necessary to provide the best evidence. Americans prize advances in technology. However, if in major medical challenges, such as osteoporotic vertebral compression fractures, the alternative is to pay the cost of perpetual uncertainty, we need to support the research necessary to provide sufficient efficacy and safety information for patients to make a truly informed choice. Although the trials by Kallmes et al. and Buchbinder et al. provide the best available scientific evidence for an informed choice, it remains to be seen whether there will be a paradigm shift in the treatment of vertebral compression fractures with vertebroplasty or similar procedures.

That is indeed the question, isn’t it? Here’s the challenge. Given these two rather definitive randomized studies showing in essence no benefit for vertebroplasty over a placebo intervention, what will we as science-based physicians do? Will we abandon a procedure against which the evidence has been accumulating, culminating in two large randomized studies that found no real benefit in terms of pain relief? Unlike homeopathy, for instance, vertebroplasty has a complication rate. It’s low, but it’s there. Harm can be done, and these studies suggest there is no benefit to make the risks worthwhile. Or will we behave as CAM advocates behave and refuse to believe because we know from our own experience that it “works”?

What will we do?

Dr. Weinstein, ironically enough, suggests what may well happen:

In an interview, Dr. Weinstein, who does not perform vertebroplasty, suggested that rather than abandoning the procedure, doctors could let patients decide for themselves, by telling them, “This is a treatment option no better than a placebo, but if you want to consider a placebo because you might benefit from it, you might want to know that.”

A $3,000 placebo? If given the choice between a pricey $3,000 placebo and a CAM placebo like acupuncture, which is likely to cost less than that and not have the potential for complications, I would pick the acupuncture, quite frankly, because the potential for harm is less than sticking needles into vertebrae and injecting cement. Really, if allegedly science-based practitioners make this sort of argument, then why not just offer CAM to patients as a placebo?

Here’s my prediction. These studies will not be enough to change practice, at least not in the short term. Vertebral compression fractures are a serious problem for which other treatment options (bed rest, pain killers, and back braces while the fractures heal) are both slow and not palatable to patients or physicians, who want immediate results. However, unlike CAM practitioners, eventually physicians will yield to the weight of the negative evidence. There may be a few more studies, and it’s even possible that there may be found a subgroup of patients who actually do benefit from vertebroplasty, but eventually the procedure will either be abandoned or scaled back to patients who might actually benefit from it. The process may be far messier than we would like. It may take far longer than we would like. It may even take a turnover to a new generation of physicians for the process to be complete. But, make no mistake, science will win out.

Science-based medicine, in contrast to CAM, is inherently self-correcting. The problem is that we as science-based practitioners are just as prone to the same sort of thinking that causes CAM remedies that are no more effective than placebo persist against all negative scientific evidence. It’s a fact that we can easily forget if we are not careful. If we forget that we are just as prone to being fooled by personal anecdotal experience as any CAM practitioner, then we will be no different than they, the only difference being our choice of placebo-based therapies.