The ongoing upward trend in obesity in America.

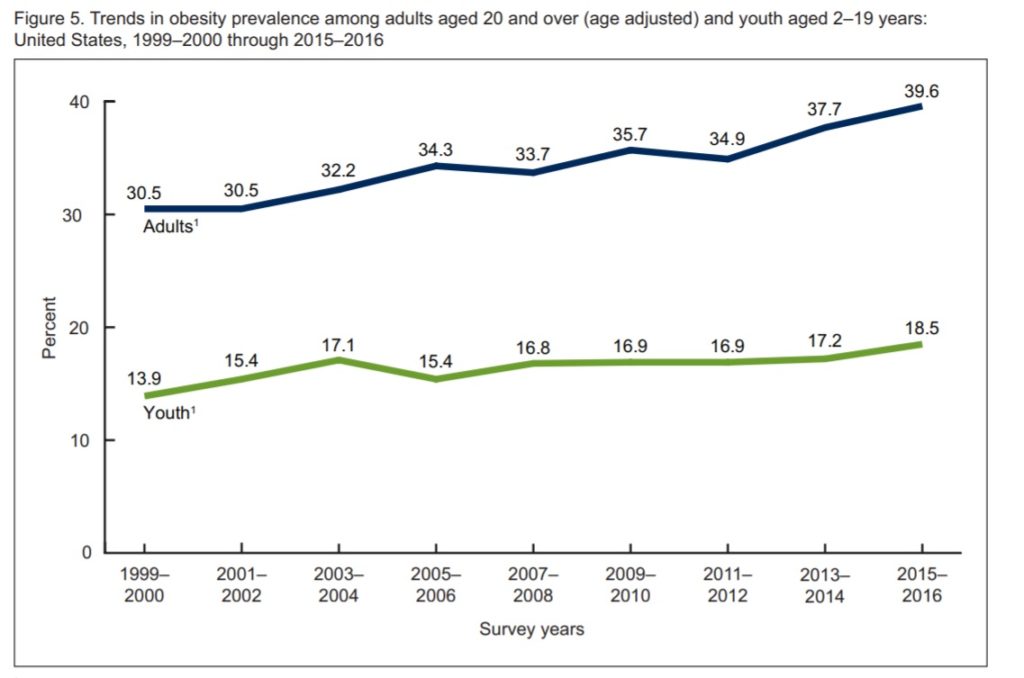

The obesity epidemic continues relentlessly across the globe, despite the increasing attention being paid to it. The latest CDC statistics (as of 2016) show that 39.6% of adult Americans are obese, with every state having a rate >20%. This is an increase from 2011 – 34.9%. In fact, the trend has accelerated. The same is true world-wide. As of 2016 there were 650 million obese adults worldwide. This is no longer a problem of just industrialized nations, and obesity can occur alongside malnutrition. The figures have tripled since 1975.

Despite these alarming numbers, there remains a fringe of “obesity denial”, which I first discussed in 2011. There are two main elements to this denial. The first is the notion that people are not really getting fatter, that it is just a trick of statistics. This is clearly not true, as the trends over the last 8 years further demonstrate. Second, there is the notion that overweight and obesity may exist, but are not in and of themselves unhealthy. This is also not true, but takes a bit more data to unpack.

The counter claim is that obesity correlates with other things that are unhealthy, such as a poor diet, lower socioeconomic status, and less access to health care, but is not an independent risk factor for disease. This is the “fat but fit” hypothesis. This has always been a minority opinion among experts, but a plausible interpretation of the data, resulting in some controversy. This is because the data, by necessity, is observational. You cannot make people get fat to see if they are more likely to die from disease. Correlational data leaves the door open for multiple interpretations of cause and effect.

However – this does not mean we cannot arrive at confident conclusions based on observational data alone. The trick is to control for as many plausible confounding factors as possible, and to triangulate to the most likely cause and effect. The “fat but fit” outliers served a useful purpose in this regard – making sure the broader scientific community did not settle prematurely on the simplest interpretation of the data. The stakes are pretty high here as well. We want to focus our public health and individual efforts on addressing the real health risks, and not be distracted by something that may be ultimately cosmetic.

At this point, however, I think we can say that the data is in. The “fat but fit” hypothesis is all but dead. Multiple large studies have reasonably isolated obesity as an independent risk factor. A 2018 study in the European Heart Journal looked at almost 300,000 people prospectively. They first evaluated them for their metabolic health – diabetes, blood pressure, cholesterol – and then tracked their health over four years. They found that waist size was an independent risk factor for heart disease and strokes. Further, there was a “dose response” effect – the bigger your waist, the higher your risk.

Further, being overweight is an independent risk factor for other things which themselves carry further risk – such as sleep apnea, diabetes, certain cancers, and arthritis.

A recent study also shows this risk extends to younger age groups. Specifically, tracking of cancer rates over the last decade show a shift in obesity-related cancers to younger age groups.

In this cross-sectional study of 2,665,574 incident obesity-associated cancer cases and 3,448,126 incident non–obesity-associated cancer cases from 2000 to 2016, the percentage of individuals diagnosed with incident obesity-associated cancers increased in younger age groups, with some of the greatest increases observed for liver and thyroid cancers (all sex- and race/ethnicity-specific strata), gallbladder and other biliary cancers (non-Hispanic black men and women and Hispanic men), and uterine cancer (in Hispanic women in the 50- to 64-year age group).

As with the global warming controversy, it seems the data is past the point where we should be debating whether or not it is happening, and whether or not it is a bad thing, and instead focus on what to do about it. Here genuine controversy remains. What we do know is that obesity is a problem worldwide, but there are regional differences. In the US, there are significant differences by state, which suggests an environmental or cultural factor.

One demographic hypothesis is that obesity is linked to urbanization, which may in turn increase access to fast foods and reduce physical activity. However, a 2019 study published in Nature found that increases in BMI in rural areas is primarily driving the obesity epidemic:

We show that, contrary to the dominant paradigm, more than 55% of the global rise in mean BMI from 1985 to 2017—and more than 80% in some low- and middle-income regions—was due to increases in BMI in rural areas.

The one thing about which there is general agreement is that the epidemic cannot be understood simply through the lens of individual behavior. This is a public health issue, relating to societal factors. A lot of blame focuses on the fast food industry. Over the last 30 years the average calorie content of a fast food meal has increased (along with salt and fat content). There is also focus on “food deserts” – locations that lack sufficient access to fresh fruits and vegetables. There is some debate about the role of sedentary life style, although it seems the evidence supports the conclusion that obesity is largely due to excessive caloric intake.

Overweight and obesity is a complex behavior problem without a known consistently effective solution. The primary problem may be that we evolved in an environment that was calorie restricted and now we have access to calorie abundance. The food industry competes with increasingly tasty products, and that means more calories. Health and dieting fads have apparently not been helping.

What is likely necessary is a significant change in the culture of food, but that is not something that is easily changed, or really in the power of any one organization or institution to change. That is why we debate endlessly about the causes and solutions to the obesity epidemic, while the numbers continue to worsen and even accelerate.