There can be no doubt that, when it comes to medicine, The Atlantic has an enormous blind spot. Under the guise of being seemingly “skeptical,” the magazine has, over the last few years, published some truly atrocious articles about medicine. I first noticed this during the H1N1 pandemic, when The Atlantic published an article lionizing flu vaccine “skeptic” Tom Jefferson, who, unfortunately, happens to be head of the Vaccines Field at the Cochrane Collaboration, entitled “Does the Vaccine Matter?” It was so bad that Mark Crislip did a paragraph-by-paragraph fisking of the article, while Revere also explained just where the article went so very, very wrong. Over at a blog known to many here, the question was asked whether The Atlantic (among other things) matters. It didn’t take The Atlantic long to cement its lack of judgment over medical stories by publishing, for example, a misguided defense of chelation therapy, a rather poor article by Megan McArdle on the relationship between health insurance status and mortality, and an article in which John Ioannidis’ work was represented as meaning we can’t believe anything in science-based medicine. Topping it all off was the most notorious article of all, the most blatant apologetics for alternative medicine in general and quackademic medicine in particular that Steve Novella or I have seen in a long time. The article was even entitled “The Triumph of New Age Medicine.”

Now The Atlantic has published an article that is, in essence, The Triumph of New Age Medicine, Part Deux. In this case, the article is by Jennie Rothenberg Gritz, a senior editor at The Atlantic, and entitled “The Evolution of Alternative Medicine.” It is, in essence, pure propaganda for the paired phenomena of “integrative” medicine and quackademic medicine, without which integrative medicine would likely not exist. The central message? It’s the same central (and false) message that advocates of quackademic medicine have been promoting for at least 25 years: “Hey, this stuff isn’t quackery any more! We’re scientific, ma-an!” You can even tell that’s going to be the central message from the tag line under the title:

When it comes to treating pain and chronic disease, many doctors are turning to treatments like acupuncture and meditation—but using them as part of a larger, integrative approach to health.

No, that’s what they say they are doing (and—who knows?—maybe they even believe it), but what that “integrative” approach to health actually involves is “integrating” quackery like acupuncture with scientific medicine. Elsewhere, in her introduction to the article in which she explains why she did the story, Rothenberg Gritz describes a visit to the National Center Complementary and Integrative Health (NCCIH), which is how the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM) was renamed last December:

After visiting the NIH center and talking to leading integrative physicians, I can say pretty definitively that integrative health is not just another name for alternative medicine. There are 50 institutions around the country that have integrative in their name, at places like Harvard, Stanford, Duke, and the Mayo Clinic. Most of them offer treatments like acupuncture, massage, and nutrition counseling, along with conventional drugs and surgery.

One notes that the renaming of NCCAM to eliminate the word “alternative” was a longstanding goal of NCCAM, its supporters, and “integrative medicine” advocates. The reason is obvious: “Alternative” implies outside the mainstream in medicine, and that’s not the message that proponents of integrating quackery into medicine want to promote. One can’t help but wonder if it was a retirement present for Senator Tom Harkin (D-IA), the legislator most responsible for the creation and growth of NCCAM who retired at the end of the last Congressional term. Whatever the case, the name change was, as I put it, nothing more than polishing a turd.

Be that as it may, no one, least of all here at SBM, argues that “integrative” medicine is “just another name for alternative medicine.” It isn’t, as most integrative MDs use conventional, science-based medicine as well. The problem with “integrative” medicine is that, to paraphrase Mark Crislip, mixing cow pie with apple pie does not make the apple pie taste better; i.e., mixing unscientific, pseudoscientific, and mystical quackery like acupuncture and much of traditional Chinese medicine does not make science-based medicine better. Rather, it contaminates it with quackery, just as the cow pie contaminates the apple pie.

Basically, integrative medicine is a strategy for mainstreaming alternative medicine, even though the vast majority of alternative medicine has either not been proven scientifically to be efficacious and safe, has been proven not to be efficacious, or is based on physical principles that violate laws of physics (such as homeopathy or “energy healing). Indeed, if the term “integrative medicine” were not thus, it would be a completely unnecessary moniker. The reason is, to paraphrase Tim Minchin, Richard Dawkins, John Diamond, Dara Ó Briain, and any number of skeptics, there is no such thing as “alternative” medicine because “alternative” medicine that is shown through science to work becomes simply medicine. Thus, newly validated medical treatments have no need to be called “integrative” because medicine will integrate them just fine on its own. That’s what medicine does, although admittedly the process is often messier and takes longer than we would like. Integrative medicine, like alternative medicine before it, is a marketing term that is based on a false dichotomy. Only unproven or disproven medicine needs the crutch of being “integrative,” a double standard that asks us to “integrate” unproven treatments as co-equal with science-based medicine even though they have not earned that status.

Unfortunately, this is a false dichotomy that Rothenberg Gritz promotes wholeheartedly. The only hint of skepticism is a brief passage near the beginning in which she refers to Paul Offit’s 2013 book, Do You Believe in Magic? The Sense and Nonsense of Alternative Medicine and briefly quotes him saying what I’ve been saying all along, that “integrative medicine” is a brand, a marketing term, rather than a specialty. She also noted his criticism in his book of what is now NCCIH, and includes a quote by Dr. Offit about Josephine Briggs (the current director of NCCIH) that she “certainly was very nice” and assured him that they “weren’t doing things like that any more” (referring to “things” NCCCIH studied in the past, like distance healing, and magnets for arthritis). This is, of course, hardly even a criticism at all, but rather getting Dr. Offit to state for her Dr. Briggs’ frequent claim that NCCIH doesn’t study pseudoscience any more. It’s a claim she made when Steve Novella, Kimball Atwood, and I met with her five years ago, and, yes, back then Dr. Briggs was also very nice to us, although she did rapidly turn around and, in a painful fit of false balance, use that meeting as evidence of her even-handedness in meeting with both critics and homeopaths. It’s a claim embedded in the 2011-2015 NCCAM strategic plan, which I now like to characterize in talks as “Hey, let’s do some real science for a change!” In any case, Rothenberg Gritz’s account isn’t false balance. It’s no balance at all, with the token skeptic role taken by Dr. Offit.

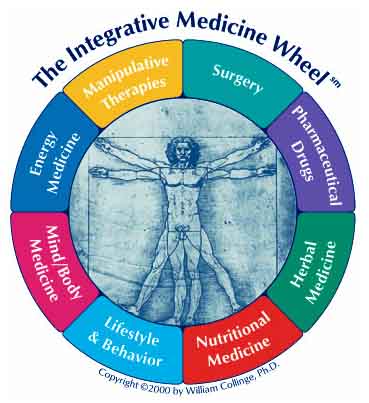

The Integrative Medicine Wheel — A good example of the branding of integrative medicine.

Revisionist history about NCCIH

Advocates for “integrative medicine” have used a variety of talking points over the years, and Rothenberg Gritz hits most of them in her article quite credulously. Indeed, it is very clear from her introduction that she was predisposed to believe. Early in the article, she tells the tale by looking back to the early 1990s, when she was in high school and her father was a family physician who was clearly into some woo, including Transcendental Meditation, Ayurveda, and the like, even going so far as to incorporate them into his practice. The inescapable implication is that she considers her father a trailblazer for what is now integrative medicine.

Unfortunately, it is very clear that her knowledge of history in this area, particularly how NCCAM/NCCIH came to be, is sorely lacking, which leads her to parrot the version of history that integrative practitioners want you to believe:

Back in the 1990s, the word “alternative” was a synonym for hip and forward-thinking. There was alternative music and alternative energy; there were even high-profile alternative presidential candidates like Ross Perot and Ralph Nader. That was the decade when doctors started to realize just how many Americans were using alternative medicine, starting with a 1993 paper published in The New England Journal of Medicine. The paper reported that one in three Americans were using some kind of “unconventional therapy.” Only 28 percent of them were telling their primary-care doctors about it.

And:

Enough Americans had similar interests that, in the early 1990s, Congress established an Office of Alternative Medicine within the National Institutes of Health. Seven years later, that office expanded into the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM), with a $50 million budget dedicated to studying just about every treatment that didn’t involve pharmaceuticals or surgery—traditional systems like Ayurveda and acupuncture along with more esoteric things like homeopathy and energy healing.

Now there’s some revisionist history! The word “alternative” was just popular because there was so much other “alternative” stuff (alternastuff?) going on in the early 1990s! But it’s not the 1990s any more; so “alternative” isn’t as cool as it used to be. Of course, the word “alternative” as applied to quackery dates back at least to the 1960s.

Longtime readers know how NCCAM really came about. One wonders if Rothenberg Gritz ever came across Wally Sampson’s classic 2002 article, “Why the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM) Should Be Defunded” or Kimball Atwood’s “The Ongoing Problem with the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine“. Even if you buy into the false notion that NCCIH (née NCCAM) has completely reformed itself and doesn’t study or promote quackery any more, a history lesson is important. What really happened matters.

Basically, Sen. Tom Harkin was a believer in a lot of alternative medicine. Thus, in 1991 he used his power as the chair of the Senate Appropriations Committee to create the precursor to the NCCIH. His committee declared itself “not satisfied that the conventional medical community as symbolized at the NIH has fully explored the potential that exists in unconventional medical practices” and, to “more adequately explore these unconventional medical practices,” ordered the NIH to create “an advisory panel to screen and select the procedures for investigation and to recommend a research program to fully test the most promising unconventional medical practices.” This advisory panel became the first incarnation of NCCIH, the Office of Unconventional Medicine, which was quickly renamed the Office of Alternative Medicine (OAM).

This next part is very important. NIH didn’t request this new office. There were no scientists and physicians in the NIH leadership clamoring for such an office. Congress didn’t respond to a “groundswell” of support to establish this office. The NEJM article cited by Rothenberg Gritz wasn’t even published until nearly two years after Harkin had already started the wheels rolling and a year after the founding of OAM. No, a single powerful senator with a proclivity for quackery used his power to get this enterprise off the ground, and he continued to nurture it over his remaining two decades in the Senate. The OAM was, in essence, imposed on a correctly-unwilling NIH, and has been ever since. Indeed, after she left as NIH director, Bernardine Healy revealed that she had considered the project to link research scientists with true believers in therapies like homeopathy to conduct experiments as foreshadowing nothing but disaster, but conceded that the NIH had “had no choice” because it couldn’t refuse to carry out a mandate from Congress.

And, make no mistake, Harkin was big into quackery, not to mention being in the pockets of quacks:

Harkin had been urged to take this legislative step by two constituents, Berkley Bedell and Frank Wiewel. Bedell, a former member of the House, believed that two crises in his own health had benefited from the use of unconventional medicine: colostrum derived from the milk of a Minnesota cow, he held, had cured his Lyme disease; and 714-X, derived from camphor in Quebec by Gaston Naessens, had prevented recurrence of his prostate cancer after surgery. Bedell, giving evidence of his Lyme disease recovery at a Senate committee hearing, observed: “Unfortunately, Little Miss Muffet is not available to testify that the curds and whey which she was eating are safe.” Wiewel had long been a vigorous champion of immunoaugmentative therapy for cancer, scorned by orthodox specialists; made in the Bahamas, this mixture of blood sera was finally barred from import by the Food and Drug Administration. Wiewel then began operating from his home in Otho, Iowa, an agency called People Against Cancer, a referral service for cancer treatments that orthodox medicine considered questionable.

Harkin, having lost two sisters to cancer, was susceptible to an interest in alternative therapies. Soon after sponsoring the law that launched the Office of Alternative Medicine, Harkin himself became a true believer in an unorthodox “cure.” On Capitol Hill, Bedell introduced the senator to Royden Brown of Arizona, promoter of High Desert bee pollen capsules. Harkin suffered from allergies; persuaded by Brown to take 250 bee pollen capsules within five days, he rejoiced that his allergies had disappeared. The senator did not know at the time that Brown had recently paid a $200,000 settlement under a consent agreement with the Federal Trade Commission, promising to cease disguising television infomercials as objective information programs and to stop including in his scripts dozens of false therapeutic claims for his capsules. These promotions also averred that “the risen Jesus Christ, when he came back to Earth,” had consumed bee pollen; a more recent customer, Brown’s infomercial declared, was Ronald Reagan. Brown later wrote Hillary Clinton, warning that her husband should begin dosing with bee pollen lest he develop fatal throat cancer.

So NCCIH started out at the urging of two quack constituents of Harkin; then Harkin became a believer himself. Not surprisingly, it soon became clear that the OAM was not intended to rigorously study alternative medicine, but rather to provide a seemingly scientific rationale to promote it. The office was initially set up with an acting director and an ad hoc panel of twenty members, many of whom Harkin hand-picked, including advocates of acupuncture, energy medicine, homeopathy, Ayurvedic medicine, and several varieties of alternative cancer treatments. Deepak Chopra and Bernard Siegel were also included. Critics of quackery were consulted and considered for panel membership but—surprise, surprise!—were not selected. These pro-alt med panel members became known in the OAM as “Harkinites.”

Against this background, the first director of the OAM, Joseph M. Jacobs, almost immediately ran afoul of Harkin by insisting on rigorous scientific methodology to study alternative medicine. To get an idea of what Jacobs was up against, consider that in 1995 the inaugural issue of Alternative Therapies in Health and Medicine featured not just one, but two, commentaries by Senator Harkin, “The Third Approach” and “A Journal and a Journey“. In these two articles, Harkin basically introduced the new journal as a “journey—an exploration into what has been called ‘left-out medicine,’ therapies that show promise but that have not yet been accepted into the mainstream of modern medicine.” and explicitly stated that “mainstreaming alternative practices that work is our next step.” Unfortunately, he had a bit of a problem with the way medical science goes about determining whether a health practice—any health practice—works and railed against what he characterized as the “unbendable rules of randomized clinical trials.” Citing his use of bee pollen to treat his allergies, went on to assert, “It is not necessary for the scientific community to understand the process before the American public can benefit from these therapies.” It is an attitude that did not change. In 2009, Harkin famously criticized NCCAM thusly:

One of the purposes of this center was to investigate and validate alternative approaches. Quite frankly, I must say publicly that it has fallen short. It think quite frankly that in this center and in the office previously before it, most of its focus has been on disproving things rather than seeking out and approving.

Truly, this was a profound misunderstanding of how science works. Also, the reason NCCAM had failed to “validate alternative approaches” is because they were, largely, pseudoscientific quackery that, as expected, failed scientific testing.

Ultimately Jacobs resigned under pressure from Harkin, who repeatedly sided with the quacks. It also didn’t help that Jacobs complained about various “Harkinites” on the advisory panel who represented cancer scams such as Laetrile and Tijuana cancer clinics. That Jacobs became tired of fighting and finally resigned is especially noteworthy given that Jacobs himself had been picked to run OAM precisely because of his openness to the idea that there were gems to be found in the muck of alternative therapies. Meddling by Harkin was a theme that kept repeating itself. Later, in 1998 after the then-NIH director had tried to impose more scientific rigor on the OAM, Harkin sponsored legislation to elevate the OAM to a full center, and thus was the NCCAM born. Not coincidentally, the NIH director has much less control over full centers than over offices.

Bad science and revisionist history about how alternative medicine evolved into “integrative” medicine

The key message promoters of unscientific medicine hammer home again and again is that they’re not quacks. Oh, no. They’re real scientists and don’t use medicine that’s not scientifically proven. Rothenberg Gritz drives that point home thusly:

But I was intrigued by the NIH center’s name change and what it says about a larger shift that’s been going on for years. The idea of alternative medicine—an outsider movement challenging the medical status quo—has fallen out of favor since my youth. Plenty of people still identify strongly with the label, but these days, they’re often the most extreme advocates, the ones who believe in using homeopathy instead of vaccines, “liver flushes” instead of HIV drugs, and garlic instead of chemotherapy.

In contrast, integrative doctors see themselves as part of the medical establishment. “I don’t like the term ‘alternative medicine,'” says Mimi Guarneri, a longtime cardiologist and researcher who founded the Academy of Integrative Health and Medicine as well as the integrative center at Scripps. “Because it implies, ‘I’m diagnosed with cancer and I’m going to not do any chemo, radiation, or any conventional medicine, I’m going to do juicing.'”

As I characterized it, “We’re not quacks! We’re not quacks!” Later Rothenberg asserts:

The actual treatments they use vary, but what ties integrative doctors together is their focus on chronic disease and their effort to create an abstract condition called wellness. In the process, they’re scrutinizing many therapies that were once considered alternative, subjecting them to the scientific method and then using them the same way they’d incorporate any other evidence-based medicine.

Except that that’s not the case. Here are a couple of examples that I like to use to show why this characterization of integrative medicine is a delusion.

First, I like to cite a certain medical society that I’ve butted heads with on more than one occasion and whose leadership really, really doesn’t like me, namely the Society for Integrative Oncology, declaring that it has “consistently encouraged rigorous scientific evaluation of both pre-clinical and clinical science, while advocating for the transformation of oncology care to integrate evidence-based complementary approaches. The vision of SIO is to have research inform the true integration of complementary modalities into oncology care, so that evidence-based complementary care is accessible and part of standard cancer care for all patients across the cancer continuum.” Would that this were true! If that truly is the case, then how does SIO reconcile itself with the fact that its current president, Suzanna Zick, and immediate past president, Heather Greenlee, are both naturopaths, one of whom authored official SIO guidelines for the integrative care of breast cancer patients? (Even more depressingly, Zick is a naturopath working in the Department of Family Medicine at my old alma mater the University of Michigan Medical School.) That alone puts the lie to any claims SIO has of being scientific, given that naturopathy is a cornucopia of quackery and pseudoscience. In particular, homeopathy—or, as I like to call it, The One Quackery To Rule Them All—is an integral part of naturopathy as a major component of the curricula of schools of naturopathy and is a required component of the naturopathic licensing examination (NPLEX). If you don’t believe just how quacky naturopathy is, read what they say to each other when they think no one is watching; learn about how full of pseudoscience their education and practice are, as related by a self-described “apostate“; and how unethical their research can be.

Despite all this, it’s not just integrative oncology that’s embracing naturopathy. (There’s even a specialty now known as naturopathic oncology that’s advertised by places like the Cancer Treatment Centers of America.) Meanwhile a whole host of integrative medicine programs offer the services of naturopaths, including Kansas University, UC Irvine, Beaumont Hospital (in my neck of the woods!), the University of Maryland, and, of course, the Cleveland Clinic, where a naturopath runs a traditional Chinese medicine clinic, just to name a few.

Now, here’s where the second point comes in. It goes way beyond naturopathy, whose tendrils have become firmly entwined with those of “integrative oncology,” perhaps more so than with other specialties. If, as its advocates claimed ad nauseam to Rothenberg Gritz, integrative medicine is all about the science, then its approach is all wrong. Let’s put it this way. They themselves admit that many of the modalities they are using are unproven. If they truly accept that, then for them to offer such services outside of the context of a clinical trial would be as unethical as offering a non-approved drug or unproven surgical treatment to patients. Yet, as I’ve described more times than I can remember, there are quite a few academic institutions out there offering reiki, which is just as quacky, if not more so, than homeopathy, given that it postulates the existence of a “healing energy” that has never been detected and in its particulars is no different than faith healing, except that it substitutes Eastern mystical beliefs for Christian beliefs. Under the banner of “integrative medicine,” academic medical centers are offering high dose vitamin C for cancer, anthroposophic medicine, and functional medicine. Indeed, there are academic medical centers out there that offer everything from acupuncture to chiropractic to craniosacral therapy to naturopathy. Heck, the University of Maryland offers reflexology, reiki, and rolfing, none of which have any good evidence to support them, while more integrative medicine programs than I can keep track of offer acupuncture and various other bits taken from traditional Chinese medicine, even though acupuncture is nothing more than a theatrical placebo.

In other words, integrative medicine puts the cart before the horse. Hilariously, Rothenberg Gritz inadvertently undermines her own praise of the science of integrative medicine by relating that Dr. Guarneri, whom she just represented as a paragon of science who only wants to use scientifically validated treatments, offers onsite massage therapy, herbal baths, craniosacral therapy, and acupuncture, the latter two of which are pure quackery. (Oh, and she teams with naturopaths, as well.) Indeed, craniosacral therapy is such ridiculous quackery that Guarneri’s offering it pretty much eliminates any chance I’ll buy her claim of adhering to science in her practice of “integrative medicine.”

My amusement at this aside, especially irritating is Rothenberg Gritz’s description of acupuncture. After noting that chronic pain is one reason why people seek out alternative medicine, she writes:

One reason pain is so hard to treat is that it isn’t just physical. It can carry on long after the initial illness or injury is over, and it can shift throughout the body in baffling ways, even lodging in phantom limbs. Two different people can have the same physical condition and experience the pain in dramatically different ways. As the Institute of Medicine report put it, pain flouts “the long-standing belief regarding the strict separation between mind and body, often attributed to the early 17th-century French philosopher René Descartes.”

This may be why so many chronic pain sufferers are drawn to traditional medicine: The Cartesian idea of mind-body duality never found its way into these ancient systems. Acupuncture, for instance, has been shown to help with problems like back, neck, and knee pain. But it’s very hard for science to figure out how it works, since it involves so many components that are mental as well as physical. The technique of inserting the needles, the attitude of the practitioner, the patient’s own attention—all of these are built into the treatment itself. In Acupuncture Research: Strategies for Developing an Evidence Base, researchers note that ancient Chinese physicians saw the mind and body as “necessarily connected and inseparable.”

Note that the study to which Rothenberg Gritz links is the acupuncture meta-analysis by Vickers et al., which so failed to show what it claimed to show that one SBM post wasn’t enough to explain why. It required discussion by Steve Novella, Mark Crislip, and myself, much to Vickers’ dismay.

The funny thing is, mind-body dualism is not a part of modern medicine, making it odd that the IOM would get it so very, very wrong 11 years ago. Remember, the concept of dualism posits that consciousness (the mind) is, in part or whole, something separate from the brain; i.e., not (entirely) caused by the brain. Now, if there’s anything modern neuroscience has taught us, it’s that dualism is untenable as a scientific hypothesis, that the “mind” is wholly a manifestation of the function and activity of the brain—or, as it’s sometimes stated, the brain causes the mind. In other words, science-based medicine rejected mind-body dualism a long time ago. Of course, as we’ve discussed here more times than I can remember, when rigorously studied acupuncture has never been convincingly shown to do anything more than placebo. Indeed, the reason why acupuncture “outcomes” (such as they are) are so dependent on practitioner and patient is because acupuncture is placebo.

In fact, my retort to Rothenberg Gritz’s outright silly argument about mind-body dualism is that it’s the integrative practitioners who emphasize mind-body dualism, whether they realize it or not. After all, they have a whole category of therapies known as “mind-body” medicine, an implicit acceptance, at least on some level, of dualism. Nor does their overblown appropriation of epigenetic studies as evidence that the “mind heals the body” (or, as I like to refer to it, wishing makes it so), which infuses so many alternative medicine practices, help. In actuality, given that the vast majority of alternative medicine practices, when rigorously studied, do no better than placebo, this new emphasis is basically integrative medicine rebranding the pseudoscientific practices it “integrates” as “harnessing the power of placebo.” Since placebo effects require that physicians in essence lie to their patients (albeit with good intent), it’s not for nothing that Kimball Atwood and I have dubbed the placebo medicine as practiced by integrative medicine practitioners as a rebirth of paternalism in medicine due to the lure of being the shaman-healer.

The rest of the article is full of the same old pro-integrative medicine tropes that I’ve seen over and over and over again. For example, Mark Hyman, the “functional medicine guru” now trusted by Bill and Hillary Clinton who regularly mangles science about autism and cancer while advocating anecdote-based medicine, opines that we have “an acute-disease system for a chronic-disease population,” that the “whole approach is to suppress and inhibit the manifestations of disease,” and that “the goal should be to enhance and optimize the body’s natural function,” whatever that means—and whatever “functional medicine” is. (For a reminder, look at Wally Sampson’s multi-part analysis of what functional medicine is claimed to be here, here, here, here, and here.)

Rothenberg Gritz also relies on the ever-annoying “science has been wrong before” canard, listing all sorts of areas where medicine got it wrong before getting it right, as though that justifies integrating alternative medicine into science-based medicine because, I suppose, science could be wrong about that too. It does not; it’s a fallacy. She also parrots the charge that doctors haven’t thought enough about prevention, a claim that has always irritated me. After all, what are vaccines, but prevention? What are diet and drugs to treat elevated blood sugar but prevention of diabetic complications? What are antihypertensive drugs but a means to prevent the complications of hypertension, such as heart attacks and strokes? What are smoking cessation programs but a means of preventing cancer, heart disease, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, the three most deadly consequences of smoking? (Note how integrative medicine only defines “prevention” as non-pharmacologic, or “natural,” approaches.) Yes, it’s difficult to practice some forms of prevention because making lifestyle changes, such as losing weight, drinking less, smoking less, and exercising are hard. Patients don’t want to do them and have a hard time achieving them. I’ve yet to see much evidence that “integrative” medicine will do any better after having appropriated lifestyle interventions and rebranding them as somehow being “integrative.”

What is integrative medicine, anyway?

Perhaps the most inadvertently telling passage in Rothenberg Gritz’s article comes near the end:

After months of speaking to leading integrative doctors and researchers, I found that I was still having trouble summing up exactly what integrative health was all about. It’s not a specialty like obstetrics or endocrinology. There are integrative training programs and certifications out there, but none of them has been universally recognized throughout the medical profession. “At this point it’s really a self-declaration,” Nancy Sudak, the chair of the Academy of Integrative Health and Medicine, told me. “And nobody has a tool kit that includes absolutely everything. It largely depends on who you are as a practitioner.”

In other words, integrative medicine is, as I said, a brand, not a specialty. Pretty much every other specialty has a definition of what it encompasses that is clear. Integrative medicine is this fuzzy entity about which I can’t help but recall the words of Humpty Dumpty in Lewis Carroll’s Through the Looking Glass, who said scornfully, “When I use a word, it means just what I choose it to mean—neither more nor less.” So it is with integrative medicine, which is why last week integrative medicine could be defended on using a fallacious argument that science-based medicine is “nonsense” or that “Western medicine” has lost its soul, while this week I can sit back and grit my teeth reading an article regurgitating the advocate line that integrative medicine is just as scientific as science-based medicine.

Rothenberg Gritz is correct that integrative medicine has evolved, but it hasn’t evolved in the way she thinks it has. In her final paragraph, she wonders whether the rise of integrative medicine is a result of cultural shifts (which is possible) but comes to an untenable conclusion that it may be the only way to treat chronic disease. In actuality, it is only the language that has evolved. I was half-tempted to recycle the introduction to my post on how integrative medicine is a brand not a specialty, where I describe the evolution of integrative medicine, but instead I’ll just give you the CliffsNotes version instead and you can read the original in all its snarky glory if you like. In fact, you should. You won’t regret it.

Basically, starting around the late 1960s and early 1970s, in a bid to gain respectability for what was then called quackery or health fraud, the term “alternative medicine” was coined, which didn’t have all the harsh connotations of the usual language. Around that same time, James Reston, a New York Times editor, wrote about his experience undergoing an emergency appendectomy while visiting China in 1971. His story was represented as successful “acupuncture anesthesia,” when it was anything but, stimulating popular interest in “alternative” medical approaches. However, the word “alternative” implied that this was not “real” medicine, that it still was somehow unrespectable (which it was and still is, for good reason). Consequently, in the 1990s, around about the time Rothenberg Gritz was in high school admiring her dad’s woo-filled medical practice, a new term was born: complementary and alternative medicine (CAM). The idea was that you need not fear these quack medical practices because they would be used in addition to medicine, not instead of it. This term contributed greatly to the increasing embrace of CAM by medical academia, but it was still not good enough for its advocates. After all, the word “complementary” implies a subsidiary status, that CAM is not the main medicine but just icing on the cake, so to speak.

That did not sit well with advocates, who wanted their woo to be fully part of medicine, even though they didn’t have the evidence for that to happen naturally. Thus was born the current term “integrative medicine.” No longer did CAM practitioners have to settle for having their quackery be merely “complementary” to real medicine. They could use this term to claim co-equal status with practitioners of real medicine. The implication—the very, very, very intentional implication—was that alternative medicine was co-equal to science- and evidence-based medicine, an equal partner in the “integration.” Thus was further advanced the false dichotomy that has been used to justify alternative medicine from the very beginning, that a physician can’t be truly “holistic” unless he embraces pseudoscience.

The true evolution of integrative medicine is not that it has become more scientific. Rather, it is that its advocates have gotten much, much better at branding quackery as being medicine under the guise of being “holistic” and “patient-centered.” It’s a false dichotomy that I reject and that Rothenberg Gritz clearly doesn’t understand.