Ever since the coronavirus now known as SARS-CoV-2 was first identified as the cause of an outbreak of a mysterious severe viral pneumonia in Wuhan, China two and a half years ago, a disease that later spread to the rest of the world as the COVID-19 pandemic, there has been intense curiosity about the origins of the virus. The most plausible hypothesis was that, like many diseases before, SARS-CoV-2 had a zoonotic origin; i.e., it developed the ability to “jump” from an animal reservoir to humans. Far less plausible, albeit not impossible, was the hypothesis that the novel coronavirus was created in a laboratory and then escaped, either through incompetence or malfeasance, a hypothesis that became more colloquially known as the “lab leak” hypothesis. Last week, two papers were finally published in Science that, under normal circumstances, would be, if not the final nails in the coffin of the lab leak hypothesis, getting very close. One examined the molecular epidemiology of SARS-CoV-2 and the other demonstrated that the wet market in Wuhan was indeed an early epicenter of the pandemic. Steve Novella has already discussed the studies, but that’s never stopped me before, given that having a few days to look at them allowed me also to judge reactions. Let’s just say that, contrary to the assertions of some optimists, these studies haven’t made much of an impact on conspiracy theorists, other than to provide them with targets to try to discredit.

Before I get to the studies, though, let’s look at some background on the lab leak hypothesis and conspiracy theories. I do this for two reasons. First, I want to show what these studies add to what we know about the origin of SARS-CoV-2. Second, it’s been a long time since I’ve written about this issue, and I think a recap is overdue.

A brief history of the lab leak hypothesis/conspiracy theory

Since the early days of the pandemic, there has been a question of whether SARS-CoV-2 arose naturally or had escaped from a lab. The latter hypothesis didn’t start out as a conspiracy theory, as lab leaks have happened before—although none had ever caused a pandemic that caused millions of deaths worldwide, over a million in the US alone. However, it rapidly took on the characteristics of a conspiracy theory such that even those advocating the “lab leak” hypothesis often had difficulty not interspersing more serious scientific arguments with what can be only described as a dollop of conspiratorial thinking. As time went on, if anything, the lab leak hypothesis drifted further and further from legitimate science and deeper and deeper into conspiracyland, such that, try as I might, I now have a difficult time finding examples of lab leak advocates who don’t add conspiracy mongering narratives to their arguments.

Here’s what I mean. By by May 2021 it clearly had developed all the hallmarks of a conspiracy theory, complete with a coverup narrative in which China and powerful forces in the US were “suppressing” all mention of a lab leak as a “conspiracy theory”, attacks on funding sources of investigators doing research on coronaviruses, bad science in the form of anomaly hunting (Nicholas Wade and furin cleavage sites or Steven Quay and Richard Muller and CGGCGG, anyone?) in which any observed oddity in the nucleotide sequence of the virus was portrayed as clear-cut evidence of lab manipulation by scientists doing gain-of-function research (which, apparently, went very wrong), all coupled with an utter resistance to disconfirming evidence. It didn’t help, of course, that the Wuhan Institute of Virology (WIV) was not far from the wet markets that were first identified as likely sources of the outbreak and that the WIV was studying coronaviruses and thus had them on premises. Lab leak proponents are also fond of other kinds of conspiratorial thinking, such as attribution errors, weaponization of disagreements within a general consensus, shifting the burden of proof, moving the goalposts in response to disconfirming evidence, and others, all accompanied by an intense belief in a coverup at the highest levels of multiple governments.

Of course, conspiracy theories about a lab origin for a new pathogen (often as a “bioweapon” that somehow “leaked” from a biowarfare research lab) are nothing new. They inevitably arise whenever a deadly new pathogen appears to cause major outbreaks or, as in the case of SARS-CoV-2, a pandemic. It happened with HIV/AIDS, Ebola, and H1N1. For instance, there was a major conspiracy theory about HIV/AIDS that involved its creation at Fort Detrick when scientists supposedly spliced together two other viruses, Visna and HTLV-1 and then tested the results on prison inmates. (Interestingly, this turned out to be a Russian propaganda operation codename Operation INFEKTION designed to blame the AIDS pandemic on the US biological warfare program.) Other conspiracy theories include claims that HIV had contaminated various vaccines (smallpox, hepatitis B, etc., depending on the specific version of the conspiracy theory) and thereby gotten into the population. It’s therefore no surprise that almost as soon as SARS-CoV-2 was identified as the source of the initial outbreak in Wuhan, China so did conspiracy theories about a lab origin for the virus, among other things.

One of the earliest conspiracy theories had arisen by February 2020, when James Lyons-Weiler claimed to have “broken the coronavirus code“, claiming the novel coronavirus whose nucleotide sequence had been published a week or two before, was actually the result of a failed attempt to develop a vaccine for SARS, the coronavirus-caused disease that nearly became a pandemic in 2002-2003. Hilariously, he tried to claim that the novel coronavirus showed evidence of containing nucleotide sequences from a plasmid (a circular DNA construct into which scientists insert genes that can then be introduced into cells to get them to make the protein products of those genes), which, if true, certainly would have been slam-dunk evidence that SARS-CoV-2 had been created in a laboratory. Let’s just say that Lyons-Weiler, for all his claims of molecular biology expertise, made some rather glaring errors. Another variation on this theme was the claim that there were HIV sequences in the virus that indicated that the pandemic had come about as the result of a failed attempt to develop a vaccine against AIDS.

By March 2020, direct examination of the nucleotide sequence of SARS-CoV-2 had led scientists to conclude that the virus was highly unlikely to have been engineered in a laboratory. Predictably, that revelation didn’t stop the conspiracy theories claiming that the virus had been created in a lab and escaped, at least not right away. It took time and more accumulating evidence. In the meantime, distorted claims about the rarity of certain base combinations in the virus and its furin cleavage site had proliferated. Still, by late last year, it had become pretty clear that these narratives were not consistent with scientific data; so, as Steve noted, the goalposts shift (as they often do when conspiracy theories run headlong into disconfirming evidence). The “bioweapon” or lab-engineered version of the lab leak hypothesis then, as conspiracy theories tend to do, morphed into a version that was much harder to falsify, namely that the origin of SARS-CoV-2 was indeed a lab leak, just of a naturally occurring coronavirus that had been collected from bats or pangolins and stored for study at the Wuhan Institute of Virology, such as the bat virus RaTG13, which was incorrectly claimed to be a direct precursor to SARS-CoV-2. Then, of course, there were claims that workers at WIV were infected with SARS-COV-2 in November 2019, but exhaustive contact tracing failed to find these cases.

None of this is to say that the lab leak hypothesis is impossible, or even homeopathy-level improbable. As I mentioned once, lab leaks of pathogens have occurred before, although none have led to a global pandemic. Rather, conspiracy theorists simply tended to assume that because lab leak was possible that implied that it was equally likely as a natural origin, when the preponderance of evidence has long suggested the conclusion that a lab leak origin for this pandemic is incredibly unlikely. Before I move on to the studies and the reaction to them, I’ll quote Dan Samorodnitsky from over a year ago:

If the question is “are both hypotheses possible?” the answer is yes. Both are possible. If the question is “are they equally likely?” the answer is absolutely not. One hypothesis requires a colossal cover-up and the silent, unswerving, leak-proof compliance of a vast network of scientists, civilians, and government officials for over a year. The other requires only for biology to behave as it always has, for a family of viruses that have done this before to do it again. The zoonotic spillover hypothesis is simple and explains everything. It’s scientific malpractice to pretend that one idea is equally as meritorious as the other. The lab-leak hypothesis is a scientific deus ex machina, a narrative shortcut that points a finger at a specific set of bad actors. I would be embarrassed to stand up in front of a room of scientists, lay out both hypotheses, and then pretend that one isn’t clearly, obviously better than the other.

Change that to lab leak requiring a “colossal cover-up and the silent, unswerving, leak-proof compliance of a vast network of scientists, civilians, and government officials” to over two years now, and the two studies published last week just add to the difference. As was noted last year, there are a number of coronaviruses that routinely infect humans and are known to have had an animal origin and “there is no data to suggest that the WIV—or any other laboratory—was working on SARS-CoV-2, or any virus close enough to be the progenitor, prior to the COVID-19 pandemic”.

Molecular epidemiology: Two lineages likely jumped to humans

The first study comes from Joel O. Wertheim at the University of California at San Diego (UCSD) and was first authored by Jonathan E. Pekar. As is often the case with papers of this sort, the list of authors is long, with multiple labs contributing, because studies of this sort require a lot of expertise and materials and single institutions rarely have everything needed to do them.

I read the whole paper, as well as its very copious supplementary materials and figures (all 31 supplemental figures!), and although my knowledge of bioinformatics and molecular biology is not sophisticated enough to understand the finer details of the analysis, I can help to summarize the overall findings. In brief, the authors queried several large nucleotide sequence databases maintained by different countries, including the GISAID database, GenBank, and National Genomics Data Center of the China National Center for Bioinformatics (CNCB), for complete high-coverage SARS-CoV-2 genomes collected early in the pandemic, specifically by February 14, 2020. They then analyzed the sequences by computer to reconstruct the likely origin and evolution of different viral lineages and used epidemic modeling to surmise when the virus was likely introduced into the human population, as well as to reconstruct the sequence of a probable common ancestor.

The first clear finding is that it is highly unlikely that SARS-CoV-2 circulated widely in humans before November 2019. Indeed, the authors were able to use their phylogenetic analysis to estimate that the first zoonotic transfer from animals to humans likely occurred sometime around November 19, 2019, with a range from October 23- December 8. Interestingly, a news story cites Chinese government data finding that the earliest confirmed case of COVID-19 in China could be traced back to November 17, 2019, which is pretty close to the date of zoonotic transmission that this study found. On that date a 55-year-old man from Hubei province might have been the first person to have contracted COVID-19. Every day after that, one to five new cases were reported each day, and by December 15 the total number of infections stood at 27. By December 20, the total number of confirmed cases had reached 60, and then it was off to the races for the outbreak.

The second clear finding is that a single zoonotic event can’t explain the data, but rather required two such events from two different lineages, dubbed Lineage A and Lineage B by the scientists. The study found that Lineage B was the first to make the jump to humans. Tellingly, it was only found in people who had a direct connection to the Wuhan wet market. Lineage A appears to have made the jump within weeks—or even days—of when Lineage B did; it was found only in samples from humans who lived near or stayed close to the market. From the paper:

Therefore, our results indicate that lineage B was introduced into humans no earlier than late-October and likely in mid-November 2019, and the introduction of lineage A occurred within days to weeks of this event.

And:

The first zoonotic transmission likely involved lineage B viruses around 18 November 2019 (23 October–8 December), while the separate introduction of lineage A likely occurred within weeks of this event. These findings indicate that it is unlikely that SARS-CoV-2 circulated widely in humans prior to November 2019 and define the narrow window between when SARS-CoV-2 first jumped into humans and when the first cases of COVID-19 were reported. As with other coronaviruses, SARS-CoV-2 emergence likely resulted from multiple zoonotic events.

Now, I know what lab leak proponents are thinking. Two zoonotic events introducing this novel coronavirus into the human population? Isn’t that highly unlikely?

The likelihood that such a virus would emerge from two different events is low, acknowledged co-author Joel Wertheim, an associate adjunct professor of medicine at the University of California, San Diego.

“Now, I realize it sounds like I just said that a once-in-a-generation event happened twice in short succession, and pandemics are indeed rare, but once all the conditions are in place — that is a zoonotic virus capable of both human infection and human transmission that is in close proximity to humans — the barriers to spillover have been lowered such that multiple introductions, we believe, should actually be expected,” Wertheim said.

Also, as the authors noted in their discussion:

Successful transmission of both lineage A and B viruses after independent zoonotic events indicates that evolutionary adaptation within humans was not needed for SARS-CoV-2 to spread (49). We now know that SARS-CoV-2 can readily spread after reverse-zoonosis to Syrian hamsters (Mesocricetus auratus), American mink (Neovison vison), and white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus), indicating its host generalist capacity (50–55). Furthermore, once an animal virus acquires the capacity for human infection and transmission, the only remaining barrier to spillover is contact between humans and the pathogen. Thereafter, a single zoonotic transmission event indicates the conditions necessary for spillovers have been met, which portends additional jumps. For example, there were at least two zoonotic jumps of SARS-CoV-2 into humans from pet hamsters in Hong Kong (56) and dozens from minks to humans on Dutch fur farms (52, 53).

In other words, if SARS-CoV-2 was already able to infect humans, it shouldn’t be surprising that more than one introduction occurred. In any case, this study is robust evidence that the most likely origin of SARS-CoV-2 was in an animal reservoir and that it very likely it first made the jump to humans in the wet market at Wuhan in November 2019. The study did not successfully identify the intermediary animal and is observational. It is, however, powerful.

But what about the second study?

Early cases clustered

The second study has a similarly large list of authors from different institutions, with the corresponding author being Kristian Andersen. It’s a correlative study that can’t prove the origin of the pandemic by itself, but when coupled with the first study is highly suggestive that COVID-19 arose in late 2019 in Wuhan as a result of zoonotic transfer from an animal at the market to humans.

The authors examined a number of data sources for their analysis

COVID-19 case data from December 2019 was obtained from the WHO mission report (7) and our previous analyses (5). Location information was extracted and sensitivity analyses performed to confirm accuracy and assess potential ascertainment bias. Geotagged January/February 2020 data from Weibo COVID-19 help seekers was obtained from the authors (26). Population density data was obtained from worldpop.org (27). Sequencing- or qPCR-based environmental sample SARS-CoV-2 positivity from the Huanan market was obtained from a January 2020 China CDC report (data S1) (24).

Also:

To estimate the relative amount of intra-urban human traffic to the Huanan market compared to other locations within the city of Wuhan, we utilized a location-specific dataset of social media check-ins in the Sina Visitor System as shared by Li et al. 2015 (33). This dataset is based on 1,491,499 individual check-in events across the city of Wuhan from the years 2013-2014 (5-6 years before the start of the COVID-19 pandemic), and 770,521 visits are associated with 312,190 unique user identifiers. Location names and categories were translated using a Python API for Google Translate.

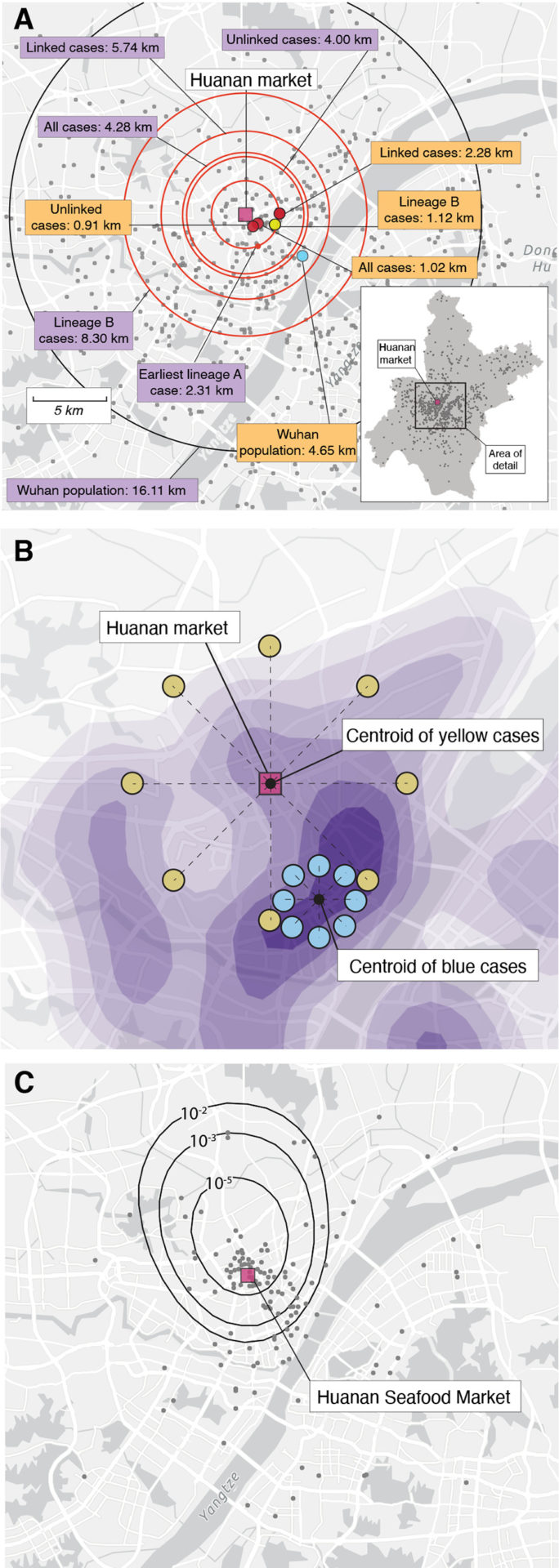

So what did the investigators find? I think a picture, specifically the spatial analyses in Figure 2, is worth a thousand words:

Fig. 2. Spatial analyses.

(A) Inset: map of Wuhan, with gray dots indicating 1000 random samples from worldpop.com null distribution. Main panel: median distance between Huanan market and (1) worldpop.org null distribution shown with a black circle and (2) December cases shown by red circles (distance to Huanan market depicted in purple boxes). Center-point of Wuhan population density data shown by blue dot. Center-points of December case locations shown by red dots (‘all’, ‘linked’ and ‘unlinked’ cases); dark blue dot (lineage A cases); and yellow dot (lineage B cases). Distance from center-points to Huanan market depicted in orange boxes. (B) Schematic showing how cases can be near to, but not centered on, a specific location. We hypothesized that if the Huanan market epicenter of the pandemic then early cases should fall not just unexpectedly near to it but should also be unexpectedly centered on it (see Methods). The blue cases show how cases quite near the Huanan market could nevertheless not be centered on it. (C) Tolerance contours based on relative risk of COVID-19 cases in December, 2019 versus data from January-February 2020. The dots show the December case locations. The contours represent the probability of observing that density of December cases within the bounds of the given contour if the December cases had been drawn from the same spatial distribution as the January-February data.

Leading to the conclusions:

Several lines of evidence support the hypothesis that the Huanan market was the epicenter of the COVID-19 pandemic and that SARS-CoV-2 emerged from activities associated with live wildlife trade. Spatial analyses within the market show that SARS-CoV-2-positive environmental samples, including cages, carts, and freezers, were associated with activities concentrated in the southwest corner of the market. This is the same section where vendors were selling live mammals, including raccoon dogs, hog badgers, and red foxes, immediately prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. Multiple positive samples were taken from one stall known to have sold live mammals, and the water drain proximal to this stall, as well as other sewerages and a nearby wildlife stall on the southwest side of the market, tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 (24). These findings suggest that infected animals were present at the Huanan market at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic; however, we do not have access to any live animal samples from relevant species. Additional information, including sequencing data and detailed sampling strategy, would be invaluable to test this hypothesis comprehensively.

And the answer to one major criticism of the hypothesis that zoonotic transfer first occurred at the Huanan market in Wuhan:

One of the key findings of our study is that ‘unlinked’ early COVID-19 patients, those who neither worked at the market or knew someone who did, nor had recently visited the market, resided significantly closer to the market than patients with a direct link to the market. The observation that a substantial proportion of early cases had no known epidemiological link had previously been used as an argument against a Huanan market epicenter of the pandemic. However, this group of cases resided significantly closer to the market than those who worked there, indicating that they had been exposed to the virus at, or near, the Huanan market. For market workers, the exposure risk was their place of work not their residential locations, which were significantly further afield than those cases not formally linked to the market.

The authors also note that the “live animal trade and live animal markets are a common theme in virus spillover events” and that markets like the Huanan market “selling live mammals being in the highest risk category,” comparing SARS-CoV-2 to SARS-CoV-1 outbreaks from 2002-2004, which were “traced to infected animals in Guangdong, Jiangxi, Henan, Hunan, and Hubei provinces in China”.

Again, is this one study slam-dunk evidence in and of itself for zoonotic transfer? No. However, the two studies together constitute powerful evidence that SARS-CoV-2 was not introduced into the human population from a laboratory, but rather transferred from animals to human, almost certainly in the Huanan market, from which is spread to the rest of Wuhan province, to China, and then to the world.

Indeed, the combination of studies was so powerful that it convinced a couple of the scientists doing the studies that lab leak is no longer a viable hypothesis to explain the origin of SARS-CoV-2:

Andersen said the studies don’t definitively disprove the lab leak theory but are extremely persuasive, so much so that he changed his mind about the virus’ origins.

“I was quite convinced of the lab leak myself, until we dove into this very carefully and looked at it much closer,” Andersen said. “Based on data and analysis I’ve done over the last decade on many other viruses, I’ve convinced myself that actually the data points to this particular market.”

Worobey said he too thought the lab leak was possible, but the epidemiological preponderance of cases linked to the market is “not a mirage.”

“It’s a real thing,” he said. “It’s just not plausible that this virus was introduced any other way than through the wildlife trade.”

That’s what real scientists (and skeptics) do. When the evidence becomes overwhelming, even if not absolutely 100% definitive, they change their minds. But will it make a difference to lab leak proponents? I think you know the answer.

Lab leak proponents react

If there’s one thing that’s true about conspiracy theorists, it’s that evidence that would tend to refute their hypotheses doesn’t persuade them to question their beliefs. Instead, it tends to make them double down. I can’t help but quote a comment after Steve’s post last Wednesday as an example, in which one of our commenters dismisses the studies solely based on this:

Anything to exculpate the elites who foisted this on us.

But there’s a lot of money going back and forth between the NIH, Big Pharma, and their CCP buddies. To appropriate a public metaphor, one hand washes the other.

Truly a clown world that we live in.

And then on Twitter the other day:

The US-funded scientists spiking the football w/ their NIH-funded paper based on public & self-edited Chinese data, is a thing to behold.

The “Funding” section of the Wuhan wet market epicenter paper has so many NIH grants, needed 2 screen shots.🧐https://t.co/wTlXgdQhMz pic.twitter.com/6suwYPhAB7

— sheila (@capitolsheila) July 30, 2022

Despicable Fauci trying to cover his Arse again.Funding: This project funded in whole or in part with Federal funds from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health (NIH) https://t.co/2PXLi9ASCj

— Ocular Deliberation (@ODeliberation) July 26, 2022

Note the conspiratorial thinking that because the NIH funded these studies that must mean they are hopelessly biased and that “Fauci is trying to cover his Arse”. This is a frequent narrative among conspiracy theorists, to personalize decisions by government agencies to a preferred bogeyman who can be attacked and to be unable to imagine that any government institution would provide research money to any group opposed to its messaging or to fund any research whose results might not line up with the message it wants to promote. I’ve discussed this issue many times before; whatever its flaws in funding mechanisms, the NIH peer review process for funding grants is arguably about as close to a true meritocracy as you will ever find in a government agency. Scientists on study sections review each grant for merit based on science, if the preliminary evidence supports their hypotheses, whether the proposed methodology is appropriate to address the scientific questions asked, if the investigators and institution are capable of carrying out the proposed research with, and the appropriateness of the budget requested. A priority score (lower is better) is assigned by the study section, and then in the best scoring grants are funded until the money runs out.

Then, just yesterday, I came across this:

I'm also looking forward to what promises to be a highly nuanced and non-conspiratorial analysis of the the recent papers (https://t.co/DBEOGUxbhN, https://t.co/QV3w210Xk3) finding lab leak to be increasingly implausible pic.twitter.com/XxiYQ5HbfD

— bad_stats 🕜💵🖨️🕣 (@thebadstats) July 31, 2022

That’s evolutionary biologist Heather Heying on the podcast that she does with her husband, biologist Bret Weinstein, claiming that it’s a conspiracy to “definitely” show that it was “those people” who caused the pandemic, not a lab leak. In a massive exercise in projection, she calls claims that the pandemic started at the Huanan market “racist,” apparently ignoring the blatant anti-Chinese racism and xenophobia behind lab leak, whose proponents often ascribe a nefarious coverup to the Chinese government, or:

Yah that was weird. I'm guessing she was trying squeeze in a talking point about how "they" would call *other* people racist for saying the virus came from the wet market, but she didn't think through it and accidentally just became an antiracist fanatic for a second

— bad_stats 🕜💵🖨️🕣 (@thebadstats) July 31, 2022

At the end, Weinstein promises to discuss these studies more in the future. Given his previous promotion of ivermectin as a cure-all for COVID-19 based on misunderstood meta-analyses, I’m sure his discussions will be as nuanced as his wife’s ascribing racism to the investigators.

Then there’s the appeal to personal incredulity:

4/ Did:

1. A pangolin kiss a Turtle?

2. A bat fly into the cloaca of a turkey and sneeze into chili.

No. But Stuart’s bit tapped into the obvious:

1. The proximity of the lab to the market.

2. The nature of the work and the virus’ at the lab.

https://t.co/iHYLaeG3ta— Brent Carpenter (@BrentCa24718741) July 31, 2022

As I like to say, just because you personally find it difficult to believe that zoonosis is the much more likely explanation for SARS-CoV-2 than lab leak does not mean that lab leak is the more viable hypothesis. Also, in that interview from last year Jon Stewart disappointed me in the extreme by sounding very much like the sort of conspiracy theorists that he used to mock on The Daily Show.

Another favorite conspiracist narrative is that the wording of the conclusions of the Science papers is less definitive than it was in the preprint versions published in February. Specifically, they’ve homed in on this sentence in the second study:

While there is insufficient evidence to define upstream events, and exact circumstances remain obscure, our analyses indicate that the emergence of SARS-CoV-2 occurred via the live wildlife trade in China, and show that the Huanan market was the epicenter of the COVID-19 pandemic.

And:

Twice now I've seen people tweet the following sentence from the introduction of our recent paper out of context:

"However, the observation that the preponderance of early cases were linked to the Huanan market does not establish that the pandemic originated there."

— Michael Worobey (@MichaelWorobey) July 27, 2022

With one conspiracy theorist from US Right to Know going on about:

A COVID origins preprint that made splashy headlines a few months ago has now been published in a scientific journal.

But the words "dispositive evidence" appear to have not survived peer review.https://t.co/fDPy4gqVZI

— Emily Kopp (@emilyakopp) July 26, 2022

And another:

And another:

And another:

The editors wanted to push this narrative.

— Florian (@Florian_Hanover) July 26, 2022

You get the idea. Lab leak conspiracy theorists seem to be perseverating on how the word “dispositive,” which was apparently used in the preprints to describe this evidence but was removed from the final versions of the studies as published in Science. To be honest, it was a mistake on the part of the authors to use a word like that, given that it is a legal term, not scientific one, meaning something that resolves a legal issue, claim or controversy. If there’s one thing I’ve learned over the years, it’s that science deniers love to substitute legal reasoning for scientific reasoning; a favorite example that I like to cite is falsus in uno, falsus in omnibus, meaning “false in one thing, false in all.” Cranks love to imaging that interrogating science is like interrogating a witness, where this legal principle allows the jury to assume that if the witness is incorrect or lies about one thing they can discount everything that witness says. Science doesn’t work like that, because the path to a scientific consensus is almost never straight and there is almost always something “false” to find if you look hard enough.

In fact, the toning down of the language in the conclusions and discussion sections of a scientific paper is a feature, not a bug, of peer review. I could point to a number of examples that I’ve personally experienced getting papers published over the last 30 years. That the final versions of the paper include more carefully nuanced language than the initial versions is not a conspiracy. It’s something that very frequently happens with peer review. Think of it this way. Scientists like to state their conclusions as clearly as possible; however peer-reviewers often see the caveats more strikingly and require toned down language. It’s normal.

Failing that, conspiracy theorists attack peer review itself:

Lab leakers will disparage any evidence that counters their theory.

— Sense Strand (@sense_strand) July 31, 2022

No one ever said, though, that peer review is anything magical. It does, however, mean that scientists carefully examined the submitted manuscript, its data, and its supplementary data and figures and decided that the data did support the hypothesis being tested and was therefore worthy of publication in the journal for which the manuscript was being considered. Again, note the conspiratorial thinking in all the criticisms:

- It’s a coverup by Anthony Fauci and the NIH (and big pharma and who knows who else).

- Anomaly hunting, in which minor issues with the papers are portrayed as fatal flaws.

- Arguments based on personal incredulity of the results.

- Cherry picking of opposing studies.

- Failure to consider the totality of the evidence and perseveration about bits of evidence that appear to support your view.

Science is a process, and definitive scientific conclusions rarely flow from a single study. The rejection of the lab leak hypothesis and conclusion that a zoonotic origin for SARS-CoV-2 is far more likely derive not from any single study—or even from these two studies—but from an accumulation of evidence obtained using different methodologies that all converge on the same conclusion. While lab leak proponents are correct that these studies don’t absolutely rule out a lab leak hypothesis, when they are taken together with existing evidence, they do deliver blows to lab leak so devastating that the hypothesis should be considered dead until and unless proponents can produce evidence sufficiently compelling to persuade scientists to resurrect it.

At this point, I can’t help but think that lab leak hypothesis has become the parrot in a classic Monty Python sketch, pining for the fjords.