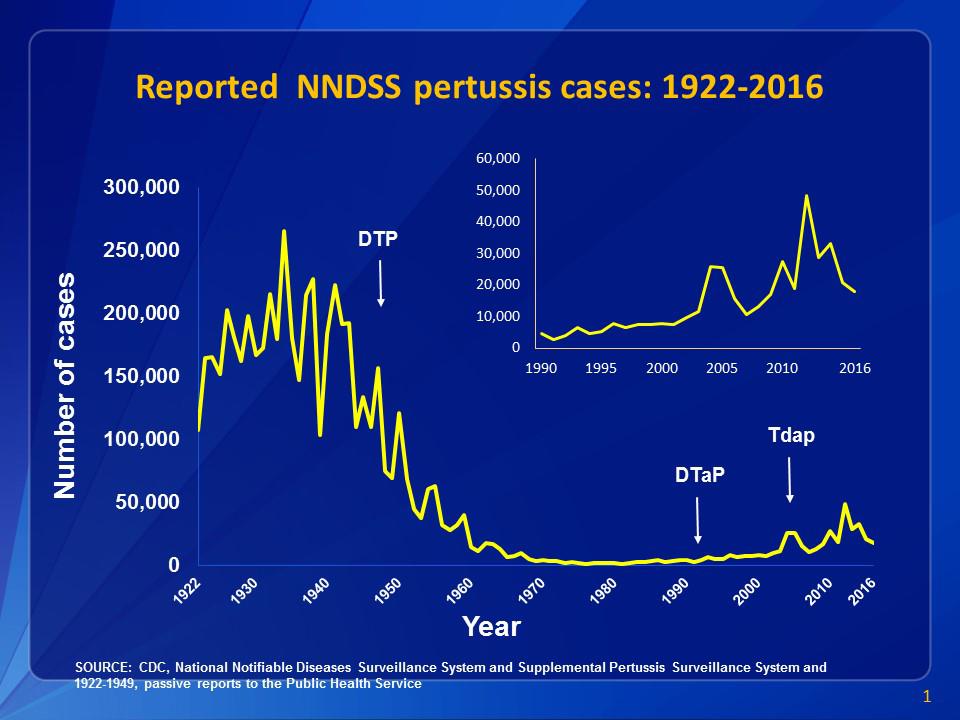

Reported cases of pertussis, 1922-2016 (source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention)

Pertussis is a highly infectious bacterial disease, also called whooping cough. It can often be serious, and even lead to death. In the 1940s a pertussis vaccine was first introduced, and this lead rapidly to a 100 fold decrease in pertussis cases in countries with an effective vaccine program.

However, since the 1970s pertussis has been making a slow comeback, even in countries with historically high vaccine uptake, like the US. Pertussis cases reached their nadir in 1976 with 1,010 cases in the US. A new study uses epidemiological data and computer models to test various theories about why pertussis is coming back. The short answer – it’s a consequence of how we designed our vaccine program. It is probably not due to any change in the vaccine itself.

The study also provides good evidence for the efficacy of the pertussis vaccine and community immunity. What they found is that when the pertussis vaccine was first introduced there was a mass vaccination program. Most people, essentially, were vaccinated over a short period of time. Most people, therefore, were either recently vaccinated or had survived a pertussis infection, which provided longer immunity. (Immunity from vaccines wanes after 4-12 years, after natural infection 4-20 years)

These factors created a “honeymoon” period in which there was excellent community immunity. This meant that even those who were not vaccinated were protected and unlikely to contract the disease. Infection rates plummeted, and it even looked like it might be possible to eradicate the disease.

As time went on, however, there were fewer and fewer adults who had long-term immunity from childhood infection. Further, immunity from the vaccine slowly decreases over time, so there were more and more adults with waning immunity.

The question for the current study is this – are these two factors alone enough to explain the slow rise in cases of pertussis over the last five decades? The authors conclude that the answer is yes. However, this does not necessarily mean that we should focus on adult vaccination. The authors also modeled interventions, and found that targeting children for vaccination would be the most effective approach to reducing pertussis cases. This is because children contribute most to the spread of the disease, while adults contribute very little, likely due to contact patterns.

Therefore the authors recommend that, in order to reverse the trend of rising pertussis cases, we make efforts to maximize compliance with the entire pertussis vaccine schedule among children. Community immunity in this population is most critical to minimizing spread of the disease.

They further conclude, contrary to what some prior research suggested, that:

Our results suggest that the train of events leading to the resurgence of pertussis was set in motion well before the shift to the DTaP vaccine.

So the reduced effectiveness of the DTaP vaccine is likely not the explanation for the resurgence. In the 1990s an acellular vaccine replaced the previous whole-cell vaccine, in order to reduce the incidence of side effects. It has been feared that the acellular vaccine is simply not as effective as the whole cell vaccine, and this still may be the case. However, it may not be the critical variable in the resurgence of pertussis. This makes sense in that the resurgence started in the 1970s, prior to the introduction of the acellular vaccine. However that does not mean that waning immunity from the acellular vaccine is not a factor.

They further conclude that eradication will not be possible without a thorough booster campaign, in order to address the issue of waning immunity from the vaccine.

The study does not mention vaccine-refusal, because that was not part of the hypothesis or analysis. It is, however, an implicit factor – if your goal is to maximize vaccine compliance, then vaccine refusal becomes a significant problem.

Also, the authors were looking at the long term trend in pertussis cases, not on pertussis outbreaks. A 2016 study looked at outbreaks and epidemics of both measles and pertussis and showed that voluntary vaccine refusal was a major contributing factor to these outbreaks. They found:

- In at least 7 statewide pertussis epidemics and multiple more geographically restricted outbreaks a substantial proportion of pertussis cases in certain age groups were unvaccinated or undervaccinated

- At least 7 pertussis outbreaks have been described in highly vaccinated populations, illustrative of waning vaccine-induced immunity

- Reasons for nonvaccination are infrequently reported in pertussis outbreaks, however in 8 outbreaks, between 59%–93% of the cases were intentionally unvaccinated or undervaccinated

- Individuals with vaccine exemptions have a greater risk for pertussis than those who are fully vaccinated

- Undervaccinated individuals—those who have received fewer than the recommended number of age-appropriate doses of pertussis-containing vaccine—also have an elevated risk for pertussis compared with fully vaccinated individuals

- Schools, communities, and states with higher exemption rates have higher rates of pertussis, including among the fully vaccinated population

- States with allowances for personal belief exemptions or with easier exemption policies have higher incidence rates of pertussis

With pertussis, because of the waning immunity from vaccines and its highly contagious nature, we need to simultaneously do several things if we want to minimize the disease. The current study shows that the most important intervention is an aggressive vaccine campaign among school-age children. In addition, we need to have booster campaigns to maintain immunity in adults.

But also clearly we need to address the false claims and fearmongering of the anti-vaccine movement that creates pockets of vaccine refusal, contributing to outbreaks and hampering community immunity. Education is the way to deal with this in the long run. However, in the short term we simply need to have effective vaccine laws. It is clear from the evidence that allowing easy vaccine exemptions reduces vaccine uptake, reduces community immunity, and contributes to outbreaks and epidemics.