The human mouth is weird and wonderful. Known in Ancient Times as “The Gateway to the Soul”,1 the oral cavity serves many roles. The teeth chew our food and aids in digestion. The saliva buffers harmful acids, contains antibodies to help control harmful oral pathogens, and is chock-full of enzymes which begin the digestive process. The tongue is a keen sensory organ, full of taste buds and sensory nerves, to not only provide enjoyment from food and drink, but to also warn us against ingesting potentially toxic substances. Our tonsils stand as sentinels against antigenic invaders, mounting robust antibody responses before they can penetrate the body further. The mouth is the starting point of the alimentary canal, and the digestive tract could not function without it. Last, the mouth is an emotive and expressive feature, revealing our feelings through smiles, frowns, grimaces, and yawns.

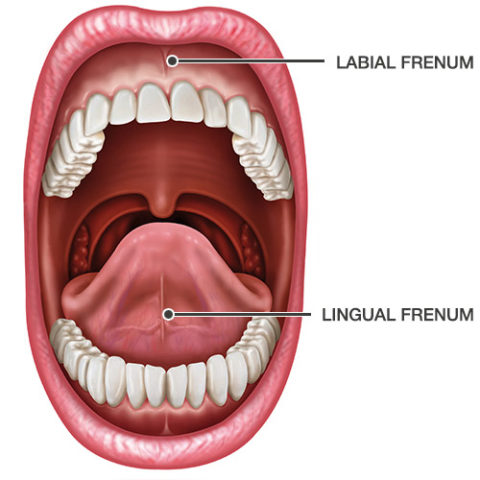

While each of these facets of our oral anatomy deserve much attention and glory, I want to focus on an oft-neglected, yet very important structure- the humble frenum (plural frena). (Note: many people call it a “frenulum;” the two terms are identical and interchangeable. Potatum-Potatulum.) A frenum is described as a membranous fold of skin or mucous membrane that supports or restricts the movement of a part or organ, and is derived from the Latin word for “bridle”. There are several frena in the mouth; notably the lingual frenum, which is the band of tissue that you see when you lift up your tongue, and the labial frena, the most notable of which are located in front of your central incisor teeth when you pull your lips out and away from your teeth.

For most of us, these harmless little mouthstrings cause no problems at all, save for the occasional poke with a Dorito which can really smart. However, there are a few potential issues that overzealous frena can cause that I want to discuss. Moreover, the issues I will cover are often overdiagnosed and overtreated; thus care must be taken to determine the proper indications, prognoses, and potential sequelae for any proposed treatment.

We’ll examine the three most common frenal problems, the treatments, and review the quality of the evidence behind these treatments.

Maxillary labial frenum

Perhaps the most common of the frenalopathies2 involves the maxillary labial frenum, which is easily seen if you pull your upper lip up. When there is a prominent frenum which attaches low on the gingiva (gums) between the two front teeth, the resulting pull on that area can cause the front teeth to separate, creating a diastema, or gap (see photo below).

If the space is less than 2 millimeters, it often will close spontaneously as a child reaches adolescence, due to the eruption of permanent teeth as well as an upward (superior) migration of the frenal attachment. In these cases, no treatment is usually necessary. However, when the space is wider than 2 millimeters and/or the band of tissue is thick and fibrous, the space likely will not close spontaneously. Moreover, if the space is closed orthodontically, it is not uncommon for the space to reopen due to the pull of the frenum on the connective tissue fibers surrounding the teeth. In this situation, surgical intervention is indicated, and the frenum is clipped or, if necessary, the entire frenum is removed.

At this point, a digression is in order so that I may describe the treatments for the conditions described here. In short, all treatment involves some sort of cutting/excising of the frenum with an instrument: a metal blade (generally a scalpel or surgical scissors), electrosurgery, or laser. There are three general procedures:

- Frenectomy: excision of the frenum left to heal by secondary intention (i.e. not sutured).

- Frenotomy: simple cutting or incision of the frenum.

- Frenuloplasty: excisions involving sutures releasing the frenum and correcting the anatomic situation.

Other, less common dental indications for maxillary frenum surgery would be if the frenum prevented a denture from fitting properly.

Mandibular labial frenum

Unlike the upper teeth, on the lower teeth, excessive pull by the frenum typically doesn’t cause spacing between the central incisors, but instead can cause severe gingival recession, which can lead to bone loss around the teeth and even tooth loss. It has been claimed that a strong frenum is a risk factor for tooth decay, but the evidence for this is weak. When the recession is only slight, a simple frenectomy is usually the treatment of choice; however in more severe cases, a frenuloplasty followed by a gingival graft to replace the lost tissue is often required (see before and after photos).

Lingual frenum

When the lingual frenum is mispositioned, it can restrict the mobility of the tongue. This is known as ankyloglossia, or “tongue-tie” Like with the other frena, this usually doesn’t cause any problems whatsoever; however, in more pronounced cases, it can have an effect on breastfeeding, speech, and jaw development and tooth position.

Breastfeeding – I’m just a dentist, not a pediatrician or Lactation Consultant, so I’m not going to weigh in too much on the indications for frenotomies on lingual frena. In some cases, the restriction of the infant’s tongue can reduce the quality of attachment to the breast or bottle as well as having a negative effect on swallowing. When this occurs, a quick and simple frenotomy (typically a quick snip with the scissors) does the trick, and the babe is back in the game. There is an excellent review examining the relationship between ankyloglossia and breastfeeding, which you can read here.

Speech – I’m just a dentist, not a speech pathologist, so I’m not going to weigh in too much on the role tongue-ties plays in speech. That said, the research is all over the map – some papers claiming that children with significant tongue ties have speech articulation issues than those who don’t, others claim little correlation, as the perception of speech articulation problems is highly subjective, and speech therapy is almost always done in conjunction with surgical correction, so benefits are difficult to ascribe.

Orthodontics – I’m just a dentist, not a…wait! I can actually field this one. Many dentists and orthodontists claim that ankyloglossia can adversely affect the growth of the mandible and cause shifting of the lower teeth, resulting in the need for orthodontic intervention, and there is some evidence that this is true. However, normal growth and development of the upper and lower jaws usually occurs in the presence of a tongue-tie, so the recommendation of surgical correction in conjunction with orthodontic treatment must be carefully weighed.

Other dental problems – Many dentists claim that tongue-ties in adulthood can cause such diverse issues as TMJ problems, headaches (including migraines), sleep apnea, “chronic fatigue”, speech issues, and many others. The scientific literature does not support any of these claims to a significant degree.

Fuzzy areas

Sadly, like with any medical or dental procedure, there is a risk of either outright fraudulent recommendations being made, or more commonly well-meaning practitioners who believe they are helping their patients, but are performing services that aren’t supported by the scientific evidence. When the patient is an infant or child, of course the parent wants to do almost anything and everything to help them, and are thus in a vulnerable position. There has been a tremendous uptick of frenum related diagnoses, especially in the dental and ENT communities. Weekend training courses in surgical correction of these disorders are everywhere, often sponsored by laser companies who claim that these “profit centers” will increase the practitioners income and will help the fancy expensive laser “pay for itself”. It can seem that in these cases, the indication for surgical correction of a frenum is the presence of a frenum. While the risks of these procedures are very low, they aren’t zero and they aren’t cheap. Recently, the concept of the “posterior tongue-tie” which is not due to a frenum at all, but merely the presence of a tight band of collagen fibers under the tongue which can’t be seen, only palpated. There is an ongoing debate in professional circles about whether this is even an anatomical or structural anomaly at all, and if so, what problems does it cause (and how). Without better research, it sounds a bit dodgy to me.

Conclusion: A real problem with fake solutions

Ankyloglossia and other aberrant frenum attachment issues are real and can have real consequences if not managed properly. However, with the significant rise in case diagnoses, as well as the number of health care professionals who are promoting treatments (which usually are not covered by insurance), one must be on guard and make sure that the decisions made are science based.

Footnotes:

- No it wasn’t. I made that up.

- I made that word up too.