“You are here early,” he said.

“Yeah. I’m trying to decide what to do about this pump and the seawater cure. So far, my attempts are falling flat.”

I told him about the couple pumping water and my lack of success in stopping them from taking the water home.

“No surprise,” said Bonham. “Water is supposed to be as safe as mothers” milk. Who would believe it is contaminated with the Cholera? I wouldn’t. What’s next?”

I held up my satchel. “This.”

“A leather bag?”

“Cute. No.” I reached into the bag and pulled out the microscope. “I brought this microscope home with me from New York. Someone, and I have no idea who, wants me to use it to examine the water and see what is in it.”

“Looking for what?” he asked.

I put the scope on a nearby picnic table. I had placed a cup in the satchel that morning, and I filled it with water from the pump.

“Animalcules. Wee beasties. And perhaps the cause of the Cholera. At least some Frenchman named Pasteur thinks so.”

“And you can see these wee beasties with that?” he asked.

“Got me. I looked at the tap water in my flat. I saw nothing in the water. No wee beasties anyway. And I examined a lot of other things in the apartment. Have you ever looked through a microscope before?”

“No,” he said.

“Me neither,” I said. “Not until this morning. It was amazing, the detail that a microscope can reveal. You would never know how complex small things are.

For a few minutes, I demonstrated the use of the microscope, showing him how hair, grass, and dirt looked under magnification.

“That is amazing,” said Bonham.

“It is,” I said. “I wish I had a bug to show you. The complexity is unbelievable. They are every bit as complicated as a human, only smaller; you just can’t see it unaided with your eyes. So, let’s see what this pump water has to offer.”

I took a drop of water from my cup, covered it with a slipcover, added a drop of oil, put it under the lens, and focused. Unlike my tap water, this drop had ghostly bean-shaped structures swimming through the water. I could not believe it.

“Animalcules,” I said. “I think I see real animalcules. Look.”

Bonham looked through the eyepiece. “Those semitransparent pill-shaped things moving around?”

“Yeah. Those were not in my tap water, although that water and this are the only liquids I have examined. Could it be they are the cause of the Cholera?” I gestured at the cup of water. “Want to take a drink and see?”

“A wonderful offer, I will admit,” he said. “But I think I will pass.”

Then it hit me. I drank from this pump yesterday. I had forgotten. Had I given myself the Cholera? I felt my stomach drop.

“What’s wrong?” asked Bonham. “You suddenly looked pale.”

“I drank from this pump. Yesterday. Before we suspected it might be the source of the Cholera.”

“Well, crap,” said Bonham.

I shook my head. “Crap, indeed.” I took in a deep breath and let it out. I would know soon enough if I got the Cholera. Nothing to do for it. I pushed down the fear. There was work to do.

“If I am going to get the Cholera, I might as well get as much work done as I can before it hits.” I looked again through the microscope. “I guess I am going to be part of the investigation. I would think drinking the water from the pump and getting the Cholera would be part of proving these animalcules are the cause of the Cholera.”

“And if you don’t get the Cholera,” asked Bonham. “What then?”

I thought for a bit. “I don’t know. Not everyone in a family gets the Cholera. So perhaps some people are resistant. Those who have had the Cholera don’t get a second case. Or perhaps there is something with the animalcules so that not everyone gets the flux. Who knows. Maybe many are called, but few are chosen.”

“Here’s hoping you are not chosen,” said Bonham.

I thought back to the Méthode Empirique. I had accomplished the first three steps. I had defined a question: what was the cause of the Cholera and how was it spread? I guess that was two questions. I had gathered information and resources and observed. Most of the information pointed to the Kenton Park pump water as the likely source of the Cholera, although it did not yet explain the cases in Lake Oswego and Hillsboro. I would have to ignore those outliers for the time being.

The next step was to form an explanatory hypothesis: it was animalcules in the water that were the cause of the Cholera. Now to prove or disprove the hypothesis. Lucky me to be part of the experiment.

It just seemed so far-fetched, since it had never been suggested that water could be the source of disease before. And to the best of my understanding, no one in the Empire had ever noted that animalcules existed, much less were the cause of contagion. Since animalcules were a Continental idea, well, that was a taboo source for information.

But that is where the evidence was leading me, and so far, I could not come up with ideas that would refute the data or the conclusions. Animalcules made more sense, or at least were more consistent, than anything the Medical Societies had to offer as a cause for the Cholera. So, for now, I would have to go with animalcules. But keep an open mind and be ready to change it.

The next steps in the Méthode were to test the hypothesis with an experiment and collecting results in a reproducible manner. I thought about the Mesmer report. They had two groups, randomly chosen. One group received animal magnetism treatment. The other received fake animal magnetism. Both groups had the same response to the therapy. They concluded that the effects of animal magnetism therapy not “real” but were in the imagination of the patient. Animal Magnetism did not produce a real, observable effect.

It would be nice to subject the treatments of the Medical Societies and the Guild to a similar comparison. Then, perhaps, we could discover which Philosophy, if any, had the one true understanding of disease and treatment. But that was a dream that would have to wait. I had other fish to fry.

So, how to do a similar study without making people take a drink of pump water?

I looked up at Bonham. “It’s a problem. How are we are going to prove the animalcules are the cause of the Cholera without giving people a potentially fatal disease? I mean, besides me. It doesn’t seem right.”

Bonham thought about it for a while. “Here is what I would do,” he said. “First, look at as many water samples as possible. See how many samples have the animalcules and how many do not. If only the pump water has the animalcules, that would be strongly suggestive they are the cause. It would be nice to examine diarrhea from a Cholera victim and see if it also contains animalcules.”

“Blech,” I said. “You would need to find the absence of animalcules in normal people. People without the Cholera. I also need to go back to as many of the quarantined houses I can to see who has been drinking pump water. Altogether, that would certainly amount to a compelling circumstantial argument that animalcules caused the Cholera and were spread by pump water.”

“The real proof,” said Bonham, “would be to have a group of people drinking the pump water with animalcules in it and a group drinking water without the animalcules and see who got the flux. I can’t see anyone with the brains God gave a goose who would do that.”

“Thanks for that vote of confidence. Give the pump water to prisoners?” I suggested. “In exchange for a commuted sentence? Or pay some people? Neither seems a good idea. And I would not want to give pump water to anyone, including a criminal, unless we had proven that the seawater remedy worked. I do not want to kill anyone testing the idea.”

“Not even someone awaiting execution?”

“Not even,” I replied. “Well, it looks like we have a plan. Let’s finish the day by looking at specimens.”

It was an exciting afternoon. We checked several samples of water from the pump. It was hard to tell for sure, but it seemed the more pumped, the fewer animalcules we saw in the water, as if they were being diluted.

We acquired multiple water specimens from the businesses around the park, and while we saw an occasional animalcule, none of these seemed to be moving with the speed of the animalcules in the pump water. The water from the slough at the north end of the park was a different matter. It was full of all sorts of animalcules, big and small, round and oblong. It was a crowded zoo of creatures, and if there were the Cholera animalcules in the mix, it would be impossible to say.

I would look at a specimen and record what I saw without telling Bonham. Then he would do the same, and then we would compare notes. It was Bonham’s idea.

“If the Mesmerists can induce an imaginary cure in their patients, why could you not cause me to see animalcules that aren’t there? They are hard enough to see as it is. It would be nice if we could stain them somehow, so they stood out.”

As we reached the end of the workday, I looked at the notebook we had been using to record the information.

“Looks pretty consistent,” I said. “The pump water is filled with very actively swimming animalcules, although it looks like the longer you pump the water, the fewer the animalcules. None of the tap water samples have similar animalcules. And the water in the slough is impossible to tell, given the tremendous number of creatures in there. I am never drinking water out of the river again, that’s for sure. But so far, we have not seen an animalcule with anything like the swimming activity of the Cholera animalcules. I wonder if brisk swimming is a defining characteristic of the Cholera animalcule.”

“Looks like it to me,” said Bonham. “Those Cholera cules move.”

“cules?”

“It’s shorter. Faster. One syllable. I don’t want to spend my life saying animalcule. It’s too short. Life, not the cule.”

“Cules it is,” I agreed.

It was 5:30, past quitting time, so I said goodbye and headed back to the office. Everyone was gone, and for once I did not run into Cassandra, probably because there was a note on my desk that said: “Do NOT forget the sisters” in big letters.

Before leaving for the day, I went to the cubby room and looked at the wall. More of the same. But it was easier to visualize the number of cases and the spread of disease. It was only getting worse.

And for the first time, there were cases outside of Kenton. Besides Lake Oswego and Hillsboro, there were over a half-dozen cases distant from Kenton, in the south and now to the east, as far as Sandy.

I looked at the wall for a long time, then sent a telegraph asking the Clackamas County Ministry how many of the cases had visited the Kenton Farmers” Market and the Cholera Festival and if they drank water from the pump. I hoped I would have an answer by tomorrow noon at the latest.

I left the office and headed over to the sisters” house.

It took a while to there. The sisters lived in an old mansion near Reed College that they had inherited from their father, who had also been a professor. It was a classic Gothic-style house that would have been the perfect setting for Baron Frankenstein to build his monster. In this case, it served as both a living space for the sisters and a place for them to experiment and play with what was likely the only private Babbage-Ada Universal Knowledge Machine in the Empire.

I started to knock on the door, and it opened immediately. I was surprised to see Cassandra.

“About time,” she said. “You are late. The sisters have more results from the UKM, and I want to go home.”

“I said about 7:30.”

“About 7:30 is 7:35. 8:00 is late.”

“Sorry. It has been a busy day.”

She led me into the basement of the house, where the sisters were sitting at the table. To my surprise, Darin Boyles was talking with them.

“Darin,” I said. “What a surprise.”

He smiled and was interrupted by a fit of coughing. When he was done, he said, “I came across one bit of information that I thought would be important. New York skeptics sent me some more information they found on the Cholera.”

“This is from papers from the same Haitian outbreak, sitting in a different box, misfiled, I guess. It is amazing how much information in the world appears to be hidden in boxes, gathering dust in basements, waiting to be discovered. There needs to be a better way to disseminate information, especially new information, rather than wait for someone from the Crown to rediscover what is already old news elsewhere. How much time and money are wasted, and how many people have suffered over a two-hundred-year-old hissy fit by the Royals? So stupid.”

He started to cough again, and Allison took the opportunity to interrupt. “Welcome, Jordan. Tea?”

“No, thank you.”

Grace continued. “Darin contacted us earlier in the day inquiring if we had your work address or a way to contact you, and I invited him here as I knew you were going to be coming around 7:30.”

“Or eight,” said Cassandra.

“Or eight. Darin has found out some curious information that ties in well with our analysis pointing to the pump as a source for the Cholera. Have you found anything of interest?”

“Oh, yeah,” I said.

I spent the next twenty minutes filling everyone in on our investigations with the animalcules and finished with my failure with the Times and the couple collecting the water from the pump.

“It is all so circumstantial,” I concluded. “And fantastical. It may convince a few people, but suggesting water contains animalcules that cause the Cholera is so outside of what people think of as the cause of disease, I do not think the concept will go anywhere. I know the Societies will not embrace it. None of them have a Philosophy that would include such a concept. I need more compelling proof.

“Like you getting the flux from drinking the water?” asked Cassandra.

“There’s that,” I said. “So, Darin. You were saying?”

“That is pretty amazing,” Darin said. “It makes what I am going to say all the more interesting. There was one group on the Island that never had the Cholera. They were a religious order, and one of their rules were they only consumed hot tea or wine. That was it. They had a bunch of other dietary restrictions: no meat, milk, fish, or eggs: nothing but vegetables. I was going to suggest that it was the animal products that spread the Cholera. But maybe it was the tea that killed the animalcules in the water.”

There was a pause while we considered it.

“No,” said Cassandra. “Boiling the water for the tea. It killed the animalcules. And it should be easy enough to demonstrate. Boil some of the pump water and use the microscope to see if the animalcules are still swimming around.”

“Great idea,” I said. “Then, to prove it is safe, do you want to drink the boiled water?”

She grimaced. “Well, what if the dead animalcules can still cause the Cholera? Some sort of toxin or poison. I would be up shit creek without a toilet.”

“Yeah,” I said. “That could be a problem. So far, it is all a hypothesis. We are still a long way from proof.” I turned to the sisters. “You have more information for me?” Grace and Allison stood up and walked over to a table on the other side of the room. On the table was a pile of papers.

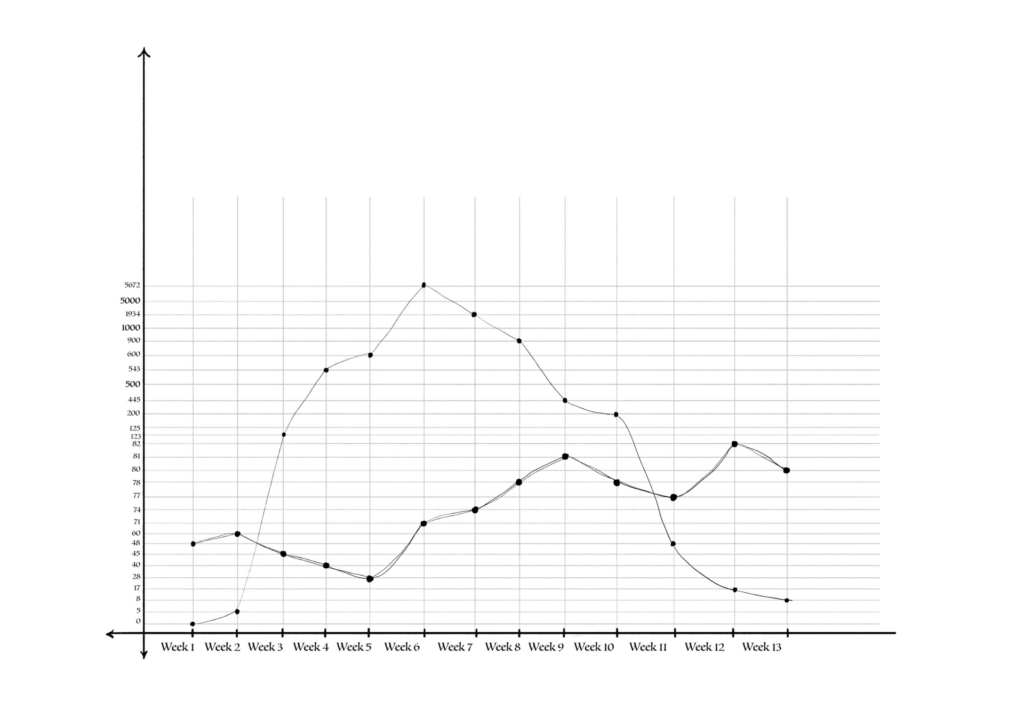

“These are graphs produced by UKM,” said Grace, “for this outbreak and for a half-dozen others for which we were able to get information. And they all look like this.”

“Note these are not straight lines; they curve ever more upwards. Cases of the Cholera start slowly but then accelerate. Right now, in Portland, there are around eight hundred cases. But if it continues to accelerate, in a month there could be fifteen thousand cases. That is assuming conditions stay the same, which they will not. People will leave, and there may be other interventions that will alter the trajectory of the Cholera. But this is how the Cholera grows. And here is some more information.”

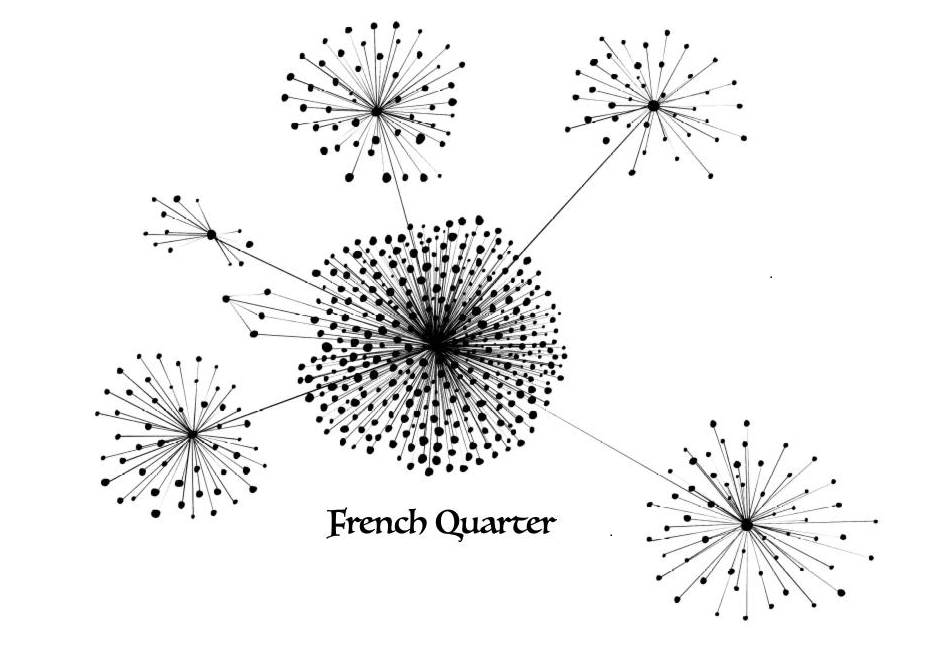

She pointed at another paper.

“This is from the New Orleans Cholera of twenty-two years ago. There were particularly fastidious at tracking cases over time. It would appear the Cholera cases increase in one area for a period of time, then spreads. It started in the French District, then a case went to another neighborhood where cases increased. Then a single case shows up at another neighborhood and it takes off there.”

“Like Lake Oswego,” I said.

“Or Hillsboro,” said Cassandra.

“Yes, like Lake Oswego or Hillsboro. And those isolated cases went on to be their own epicenters of the Cholera until they spit out a case which set up their own epicenter of the disease.”

“So, it was a single person from a Cholera epicenter that took the disease to another site?” I asked.

“As best we can tell from the information, that would be the case. Based on the information about the pump water, they either carried the animalcules in their bowels and spread it that way or somehow transported contaminated water.”

“Ick,” said Cassandra, making a face. “But I wonder. Do some people carry the Cholera and not have symptoms? That would allow the Cholera to spread unnoticed.”

I shrugged. “I do not know. That is a problem with this investigation—every answer spawns two questions.”

“Yes,” said Grace. “Uncertainty and doubt grow exponentially like the Cholera, while answers progress in a straight line.”

“That’s a problem,” I said. “At least based on the information I have, no one from the Lake Oswego or Hillsboro cases has ever been on the east side of the river.”

“You know that for a fact?”

“It is what I have been told, but I think I am going to have to confirm it myself.”

“Please,” said Grace.

“Anything else?” I asked.

“Two things. As we get more data, the association of cases with homeopathic care looks stronger, as does the association with naturopathy. But there are still huge holes in the data that make the association, let’s say, fragile. And I saved the worst for last.”

She pointed at another paper. “Some of the outbreaks of the Cholera stopped on their own, mostly in small communities where I suspect they ran out of people to infect, or everyone at risk moved away or died. Again, the information is spotty. But if you apply the growth curves of the Cholera to small populations, everyone should get the disease fairly quickly. In big cities, though, there are too many people for the Cholera to stop because everyone either got a case, died, or moved away.”

“So, what stopped it?” I asked.

“Winter. When the temperature dropped below ten degrees for a week, the disease stopped. See?”

They showed me another graph.

“This is a UKM plot of cases versus temperature. As soon as it gets cold for a long enough time, about a week, the Cholera goes away.”

“So cold kills animalcules?” asked Cassandra.

“That is the simplest explanation. Maybe animalcules can only live only in a narrow temperature range, and for them, humans are porridge—just right.”

“Well,” I said, “I can certainly boil some water to see what it does to animalcules. Someone want to bring me some ice from Mt. Hood so I can freeze the animalcules as well?”

“That is not the biggest concern. It’s June. It is going to be three or four months before it becomes cold enough to stop the Cholera. I fear if something is not done, considering the number of people in the Portland area, we are heading into thousands of cases for months before the Cholera ends by either a cold snap or everyone gets it. Or dies.”

That brought silence to the room until Daren started coughing again, breaking the spell.

“Every answer only results in more questions,” I said. “Thank you all. It looks like I have more work to do tomorrow.”

I left the sisters” house and went home for a restless night’s sleep.