Some of my colleagues have been surprised at the number of really awful papers that have been published during the pandemic and reach conclusions that are at odds with thus-far established science. Examples abound, a number of which we have written about, including articles by academics whom I used to admire (or at least view more favorably than unfavorably), such as John Ioannidis, Vinay Prasad, and a number of others, some, admittedly, noto particularly admirable before the pandemic (such as Peter Doshi). Seemingly, even the Cochrane Collaborative has gotten in on this action, along with past leaders. Most were in the peer-reviewed biomedical literature, too, although not all. (The utter crapfest of an anonymously authored study that wasn’t peer-reviewed that was published by the Florida Department of Health last fall and suggested that COVID-19 vaccines are more dangerous than COVID comes to mind. Surprise! The paper went through multiple iterations personally overseen by Florida Surgeon General Dr. Joseph Ladapo and clearly designed to make the vaccines look worse than the disease.) They shouldn’t have been. Publishing academic research articles as a form of misinformation and propaganda for quackery is a longstanding tactic used by advocates of unscientific medicine, such as proponents of alternative medicine and antivaxxers.

That’s why I’m happy that one of the most prominent physicians turned COVID-19 misinformation spreaders, Dr. Peter McCullough, reminded me of a study that I had though about blogging about a couple of weeks ago. True, it’s one of his paid Substack articles, entitled Retracted COVID-19 Articles: Significantly More Cited than Others, which he touts as evidence that “biopharmaceutical complex censorship” is “backfiring.” The study itself was published three weeks ago in Scientometrics by Trenton Taros and investigators at the University of Massachusetts and entitled Retracted Covid-19 articles: significantly more cited than other articles within their journal of origin.

Since I don’t subscribe to Dr. McCullough’s Substack (and will never pay someone like him for the privilege of reading their Substack articles), all I can cite is the first paragraph, but the first paragraph is enough to give you a good idea of what Dr. McCullough is about. Naturally, he starts by bragging about his publication record, something I always find annoying because, as I like to say, I don’t care about what he published in the past. I care very deeply about the misinformation he publishes now and has published since the pandemic hit three years ago, such as the false claim that COVID-19 vaccines are killing hundreds of thousands—or even millions—of people.

Let’s see what Dr. McCullough has to say, though:

I have 685 listings in the National Library of Medicine PUBMED where my academic contributions as a first or contributing author or as a site principle investigator have been memorialized. I am the former longstanding editor Reviews in Cardiovascular Medicine and Cardiorenal Medicine—both are indexed in PUBMED. I have handled thousands of manuscripts and can tell you first hand, historically, that retractions of fully published reports was exceedingly rare. It was only done in the most grievous cases of academic fraud that was discovered after a paper had fully made it through the peer-review process. Since the onset of the crisis, starting with early treatment of COVID-19, we have seen an unprecedented number of papers retracted after full publication and indexing in the National Library of Medicine. As an author and experienced editor, I wanted to understand what is going on in the case of pandemic paper retractions.

Before I move on to the publication that he is clearly talking about (the discussion of which I thank him for reminding me to write), let’s just unpack that last part about retractions of “fully published reports” being “exceedingly rare.” Guess what? He’s correct about that! Here’s where we disagree. He views rarity of retractions prepandemic as a good thing. I do not. I’ve long argued that there’s a lot of dreck and fraud in the peer-reviewed biomedical literature that really could use some retracting. Journals have been painfully reluctant to do that. The most notorious example, one that I like to cite a lot, is how it took 13 years for The Lancet to retract Andrew Wakefield’s infamous 1998 case series that claimed to link vaccination with the measles-mumps-rubella (MMR) vaccine to “autistic enterocolitis,” and it took undeniable revelations of scientific fraud unearthed by investigative journalist Brian Deer to finally prod The Lancet‘s editor Richard Horton to pull the trigger and retract. I could list a number of other truly awful antivax papers that we’ve written about here over the years that should be retracted and, in some cases, have been retracted, and note that, even when an awful or outright fraudulent paper is exposed as such, journal editors frequently resist retracting and then drag their heels as long as they can before finally retracting.

Before I go on to discuss the actual study that Dr. McCullough is presenting as “evidence” that “biopharmaceutical complex censorship” is “backfiring,” I’ll also mention that I’m rather surprised that this paper didn’t get more play in COVID-19 denial social media since its publication. After all, as you will see, what Taros et al found is that articles ultimately retracted by the journals that published them tend to garner more citations and engagement than other articles in the same journals (indeed, in the same issues of the same journals where the retracted papers had been originally published).

COVID-19 retractions

One key passage near the beginning of the study caught my eye because it so obviously went against Dr. McCullough’s lament about how rare retractions were back in his good old days. In brief, the authors note that the growth rate for scientific publication jumped dramatically in 2020, which, not coincidentally, was the year the COVID-19 pandemic hit:

In an age of expansion for modern medicine, coinciding with the continued growth of the internet, there has been a rapid expansion in the volume of scientific research activity and rate of publication. A 2021 study indicated a 4% annual growth in global publication output in peer-reviewed science and engineering journal articles as well as conference papers from 2010 to 2020 (National Science Board, 2021). The same study reports a 3% annual growth rate for biomedical and health sciences from 2009 to 2019, but an astounding 15% and 16% growth rate for each respectively in 2020. With this growth, new sets of academic standards for publication arise, along with increasingly important sets of ethical standards (Brand et al., 2004; Coats, 2009). As those standards are investigated and enforced, retraction of published papers from scientific journals becomes crucial to preserve scientific integrity and properly educate the general public and scientific community.

That last part, to me, is key. Retractions are quality control, not, as Dr. McCullough and his admiring COVID-19 contrarians and quacks characterize them, censorship. I will repeat yet again that the problem with biomedical literature is not that too many studies are being retracted; it’s that too few are and how difficult it is to get even those retracted. Taros et al point exactly this aspect of retractions out:

As the volume of scientific literature expands, retraction volume and rate have also increased (Nagella & Madhugiri, 2020; Steen, 2011). These retractions represent a self-corrective function built into the scientific research process to protect the integrity of the scientific method. Retraction of a published article can be initiated by the author or publisher for a variety of reasons: Institutional Review Board (IRB) violations, data errors, forgery, plagiarism, and inappropriate authorship, among others (Budd et al., 1998). A major concern for those articles which are retracted is their rate of citation prior to, and after retraction. This is particularly important if they are found in high-impact, prestigious, or influential journals, as this propagates the dissemination of false, inaccurate, or inconclusive information (Dinh et al., 2019).

This is indeed a concern. Andrew Wakefield’s fraudulent case series, for instance, was both widely cited and widely shared on social media. (In fact, Retraction Watch lists it as the second most highly cited retracted paper of all time, with 643 citations before retraction and 940 after retraction.) The authors note that “number of papers pertaining to COVID-19 which have been retracted continues to rise to over 200, based on the Retraction Watch Database (RWD) COVID-19 blog (Marcus & Oransky, 2022).” Coincidentally, I note, going over to the Retraction Watch blog’s weekend update, that the number is now up to over 300.

What the authors did was to test the following hypothesis:

We hypothesized that retracted COVID-19 articles received more attention, measured in citations, than would be expected for the average article in the journal they were published in over the same time period. In presenting a quantitative analysis of retracted COVID-19 articles published in medical and life science journals, we hope to shine light on the attention these articles garnered and provide possible rationale for this occurrence. The inclusion of SCImago Journal Ranking (SJR) is used to demonstrate that this phenomenon was not isolated to smaller journals but included journals of all sizes and prestige levels. It is our hope to add to the conversation regarding COVID-19 retractions and the state of scientific literature during the pandemic.

The authors did not include preprints (which is another topic to me entirely, given how often preprints have been weaponized by quacks in order to get their bogus studies in the public record before they’ve actually been peer-reviewed) or any paper published after 2021. That latter exclusion criteria was because the authors thought that papers published in 2022 would not have had enough time for their citation records to have stabilized.

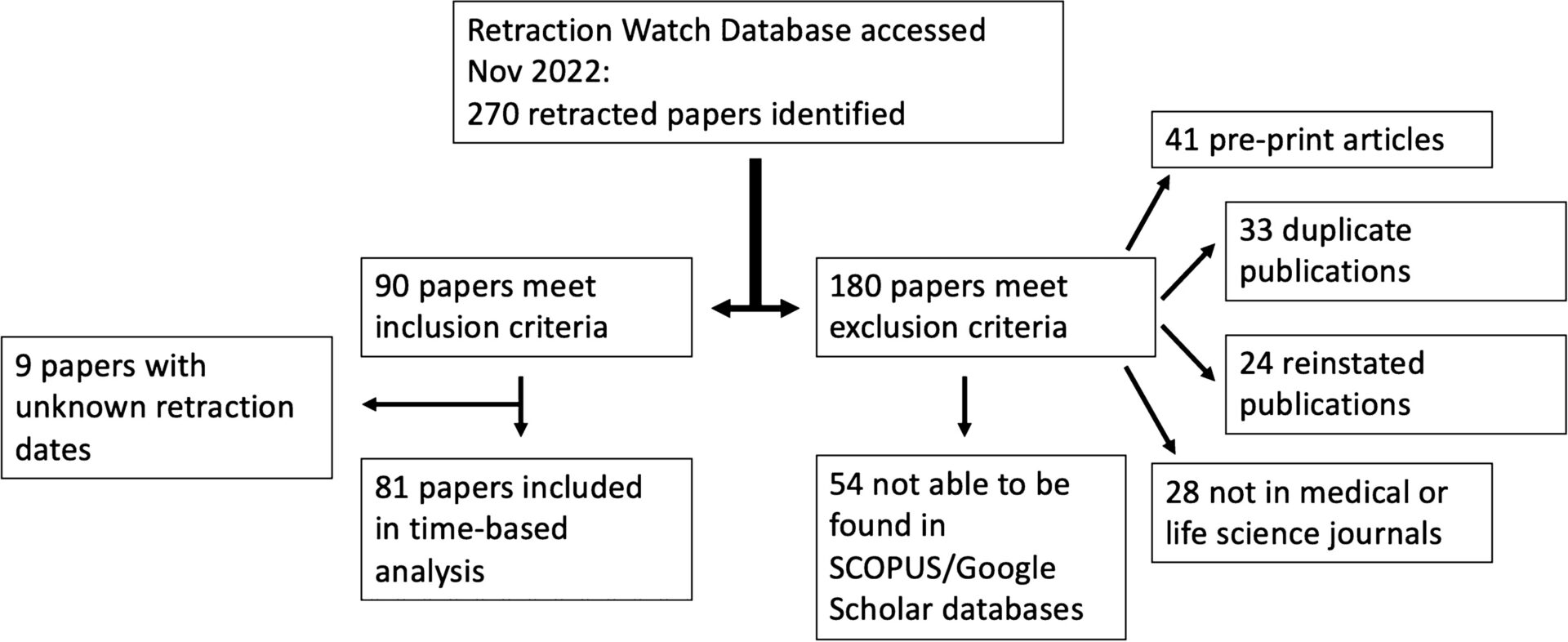

This flow diagram demonstrates what they did:

Most of the 90 retracted papers were about epidemiology, disease course, and treatments; surprisingly (to me, anyway) the percentage of papers about COVID-19 vaccines that were retracted were only one-third of the number that were about epidemiology and only one-half the number about treatment.

As for the reasons for retraction:

Those 90 articles were accessed and broadly divided into categories based on content and reason for retraction. 28 of the articles focused on epidemiology, 20 on disease course, and 22 on treatment (Fig. 2). In 53 of the cases, the publisher initiated the retraction proceedings. In 18 instances the request was initiated by the author. The requesting party was unknown in the remaining 19 instances. There were a wide variety of reasons for retraction with little standardization, at least 7 articles were retracted due to concerns for plagiarism and at least 5 for IRB violations.

I will admit that it was a pleasant surprise that over half the retractions were initiated by the publisher and that only five were retracted for IRB violations. Less pleasant was the author’s finding that 32% of the retraction statement for 32% of the retracted articles did not meet the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE) guidelines for retraction statements, which state that notices of retraction should:

- Be linked to the retracted article wherever possible (ie, in all online versions)

- Clearly identify the retracted article (eg, by including the title and authors in the retraction heading or citing the retracted article)

- Be clearly identified as a retraction (ie, distinct from other types of correction or comment)

- Be published promptly to minimise harmful effects

- Be freely available to all readers (ie, not behind access barriers or available only to subscribers)

- State who is retracting the article

- State the reason(s) for retraction

- Be objective, factual and avoid inflammatory language

The authors observe:

In only 71 cases was it possible to discern which party requested the retraction. Far fewer had clear explanations for why articles were retracted. In our analysis, 32% of retracted articles did not meet the COPE guidelines for retraction statements (Barbour et al., 2009). This is because either the retracting party or retraction reason was not included within the retraction notice. Obscuring the reason for retraction obfuscates the bravery and integrity needed to willingly retract one’s own work (Vuong, 2020). Additionally, it prevents researchers who have cited works that have since been retracted from evaluating the legitimacy of their own claims.

I can’t help but wonder how much of this disappointing lack of transparency among journals is due to concern about legal implications. If there’s one thing about society in general—and COVID-19 contrarians who publish papers like this, it’s that we live in a very litigious society. I have to wonder if the reason why so many retraction notices do not include a mention of which party requested the retraction and/or a clear explanation of the reason for the retraction is due to fear of legal liability.

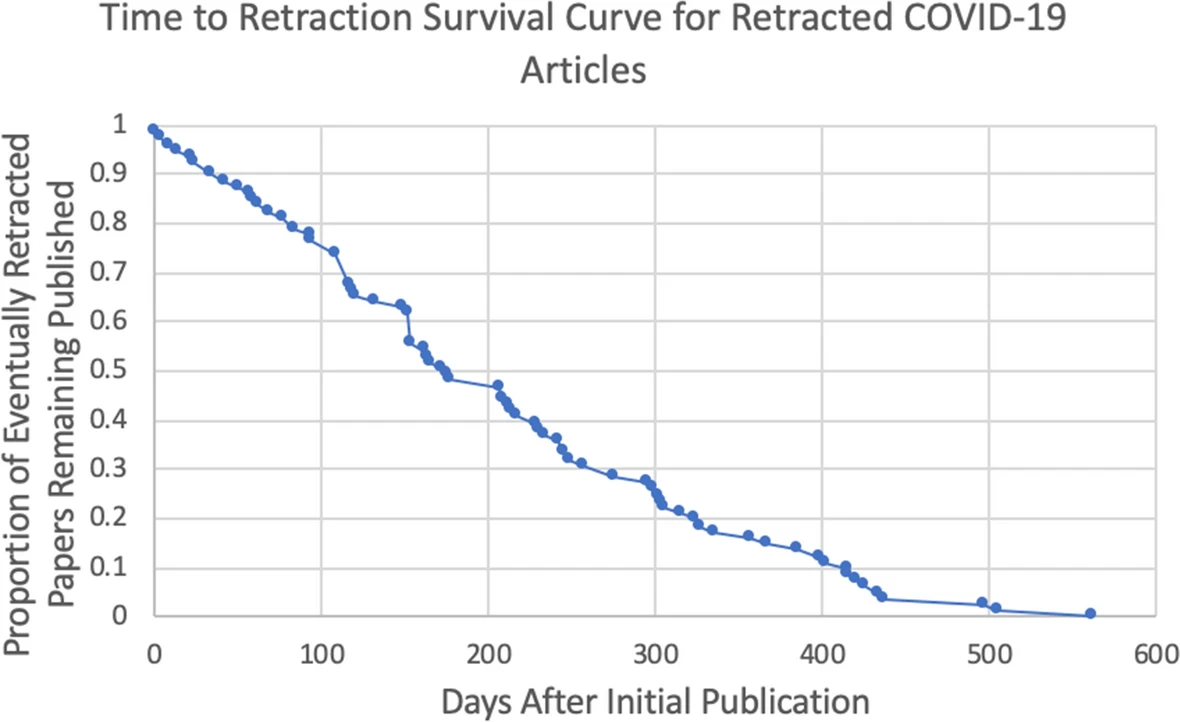

I also note that the speed of retraction does not appear to be particularly fast for COVID-19 papers, at least no more so than for any other. Take a look at this graph, which is basically a Kaplan-Meier survival curve of time from publication to retraction:

The median time from publication to retraction was 175 days, which is nearly six months! It’s impossible to tell how much of that time is delay between the time a retraction is requested to the actual retraction and how much is how long the journal takes to come to a decision, but it’s definitely not short.

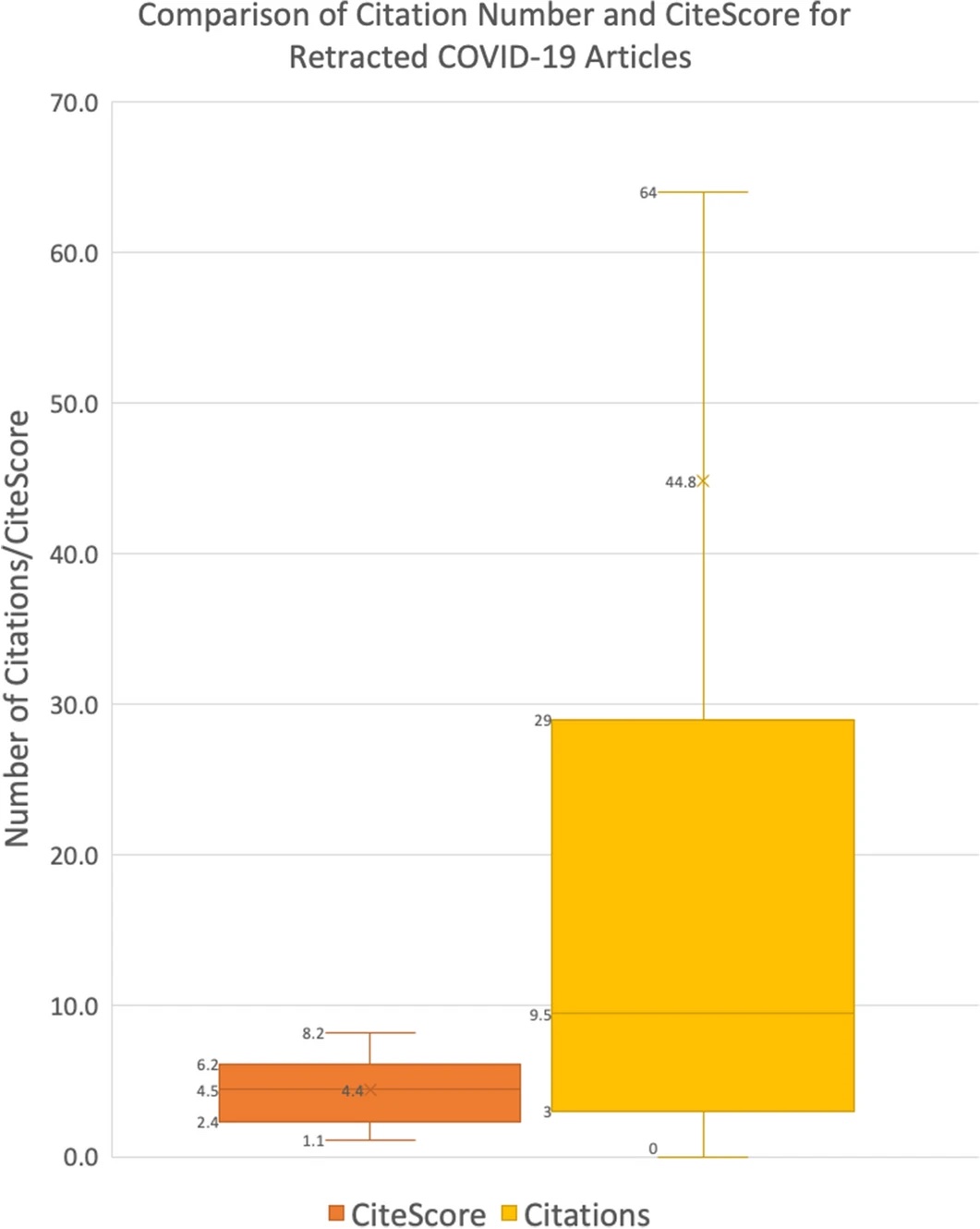

Now here’s the money finding of the paper:

Retracted articles accrued a median number of 10.0 (IQR 26) citations while CiteScore accrued a median of 4.2 (IQR 3.7) citations (Fig. 4). The difference between the average CiteScore and average citation number for a retracted article was 37.5, a statistically significant difference (p = 0.01).

Or, to show it visually:

The authors also note that by November 2020 the retraction rate for COVID-19-related papers had reached a level five times that of the general science literature, complete with clear “instances of intentional malpractice and fraudulent publications” in “some of the world’s most noteworthy journals.” This is, of course, consistent with what we at SBM have been blogging about since the very beginning of the pandemic. Noting that these papers have garnered a disproportionately high impact in the scientific literature, the authors speculate on possible reasons:

Retracted COVID-19 publications may have been more likely to include bold or novel claims that garnered a disproportionately high amount of attention from others in the scientific community. The phenomenon of “clickbait” titles could explain how certain publications gained more attention and led to further writing on a potentially misleading claim.

This is, of course, one of those findings that I intuitively sense to be almost certainly accurate, but that I cannot yet prove. Moving on, the authors conceded that COVID-19 articles in general have tended to attract more attention than other topics, because, you know, a pandemic that’s killed over a million people in just the US alone since early 2020, but argue that that alone can’t explain the difference:

It is true that COVID-19 publications accumulated a disproportionate amount of attention regardless of retraction status (Ioannidis et al., 2022). However, the large discrepancy between CiteScore and number of citations is not likely due to an increased amount of interest in COVID literature given the magnitude of the difference between CiteScore and citation number in retracted articles. A direct comparison between retracted and non-retracted COVID-19 publications for each respective journal was beyond the scope of this analysis.

This would be an interesting analysis to do. My prediction is that the difference between citation counts of retracted versus non-retracted papers would shrink but still remain substantial. Moreover, the finding that most concerns me is this:

Unfortunately, retracted COVID-19 papers continue to accumulate citations well past their date of retraction. Analysis at two time points, June and November of 2022, showed 728 total additional citations across all 93 articles analyzed across this time frame. This equates to just shy of 5 citations of retracted COVID-19 papers per day. It does not appear that measures taken to curb their citation have much effect either. For example, there was no significant difference in additional citations between those articles bearing “withdrawn” or “retracted” headings and those without them. Ultimately, this places the onus to limit the perpetuation of inaccurate, retracted information squarely on the scientific community itself. It is up to researchers to analyze their citations as closely as they analyze their conclusions.

Truly, these are what I like to refer to as either zombie studies in that they are undead and will live forever unless very specific actions are taken to kill them (e.g., a bullet to the brain), or they are “slasher studies,” named after the unstoppable killers in 1980s horror movies (like Jason Voorhees or Michael Myers) who, even after seemingly having been killed at the end of one movie, always somehow manage to live again to hunt a new group of randy teens or college students in sequels. Whichever characterization you prefer, it is up to individual scientists to vet their citations and not cite retracted papers unless the retraction is discussed or at least mentioned.

Retraction: A brief case study

I will conclude by mentioning that retraction is a two-edged sword. It is, as I have argued many times in the past, necessary quality control for the scientific literature. Unsurprisingly, cranks, quacks, and antivaxxers don’t see it that way—and never have. The most recent example is Steve Kirsch’s reaction to a very bad paper by Prof. Mark Skidmore, an economist at Michigan State University. (The shame, the shame, for my state. Even though I have no connection with MSU and never went to school there, a number of people I’ve known over the years and some of their kids have. I’ve also known some excellent faculty members at MSU.) At the time, I characterized the paper, entitled The role of social circle COVID-19 illness and vaccination experiences in COVID-19 vaccination decisions: an online survey of the United States population, as reminding me, more than anything else, of a Steve Kirsch “study” in which a fundamentally bad research design is tarted up with (some) seemingly legitimate social science research methodology and then dishonestly spun to produce a fake estimate of 278,000 fatalities due to COVID-19 vaccines, which is then “validated” by an incompetent dumpster dive into the Vaccine Adverse Events Reporting System (VAERS) database of the sort that I’ve been writing about since 2006.

Yes, you read that right. Prof. Skidmore basically did survey asking people if they knew anyone who had died after vaccination against COVID-19 and then used that survey to estimate that “the total number of fatalities due to COVID-19 inoculation may be as high as 278,000 (95% CI 217,330–332,608) when fatalities that may have occurred regardless of inoculation are removed.” Let’s just say that the survey/study was every bit as bad as it sounds from just that characterization and that it was a bait-and-switch, whose purpose was ostensibly to “identify the factors associated by American citizens with the decision to be vaccinated against COVID-19” but whose true purpose rapidly became apparent: To try to “prove” that the vaccines killed hundreds of thousands of people. Unsurprisingly, Prof. Skidmore is not a scientist with any relevant expertise in epidemiology, virology, infectious diseases, or medicine. He is an economics professor.

Fortunately, BMC Infectious Diseases, the journal that had made the mistake of publishing this bit of propagandistic pseudoscientific dreck, came to its senses and retracted it, ironically announcing it the day before the study that is the topic of this post was published, listing the reasons in a retraction notice:

The editors have retracted this article as concerns were raised regarding the validity of the conclusions drawn after publication. Post-publication peer review concluded that the methodology was inappropriate as it does not prove causal inference of mortality, and limitations of the study were not adequately described. Furthermore, there was no attempt to validate reported fatalities, and there are critical issues in the representativeness of the study population and the accuracy of data collection. Lastly, contrary to the statement in the article, the documentation provided by the author confirms that the study was exempt from ethics approval and therefore was not approved by the IRB of the Michigan State University Human Research Protection Program.

Interestingly, I myself wondered if this study had been approved by an appropriate IRB, given that it obviously should have been. Reading between the lines, I suspect that Prof. Skidmore just said that the study was exempt, but that’s not how IRB exemptions work. The IRB has to decide that the study is exempt. Often, IRB exemptions are granted through an expedited process in which the IRB chair or a subset of members examines the study protocol and decides that it falls under one of the exempt categories. It is true that the study notes that the “survey instrument and recruitment protocol of the National Survey of COVID-19 Health Experiences were approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the Michigan State University Human Research Protection Program (file number: STUDY00006960, date of approval: November 17, 2021).” However, I immediately speculated that the IRB had been duped by the aforementioned bait-and-switch and that approval had likely only covered using the survey instrument for assessing factors associated with COVID-19 vaccination uptake and refusal. I further wondered if Prof. Skidmore had conveniently left out the intended analysis in which he used the survey results to estimate how many people died from COVID-19 vaccines. I can’t prove whether or not I was correct in this speculation, but in retrospect I’m pretty sure that I was.

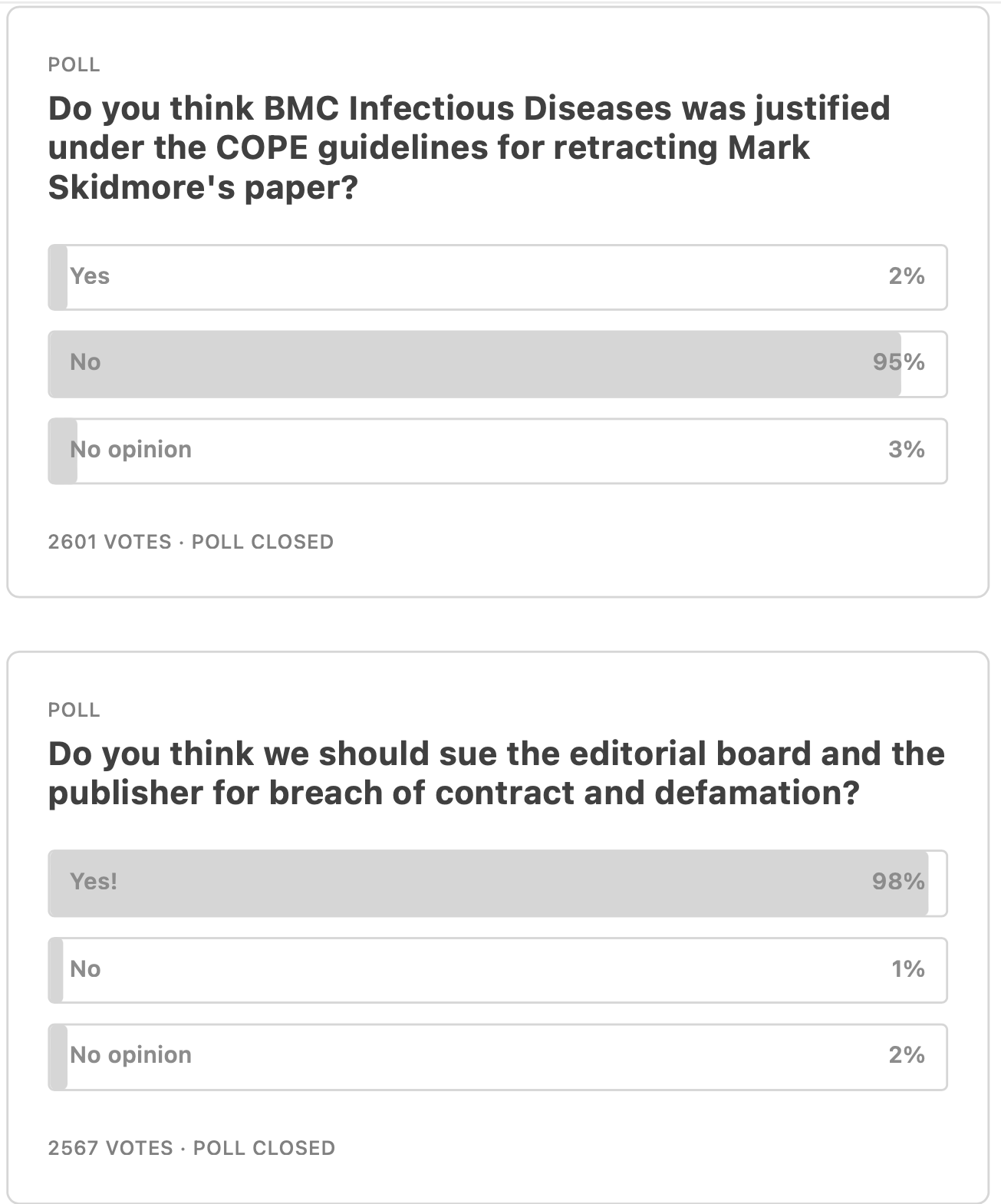

Somehow Steve Kirsch got wind of the impending retraction a few days before it was announced and, consistent with the litigious nature of quacks, posted an article to his Substack entitled It’s time we hold these people accountable; let the lawsuits begin, adding that “I’m going to pay for the lawsuit to sue Springer and their corrupt editorial board at BMC Infectious Diseases for their decision to retract the Skidmore paper; the most popular paper in their history.”

Yes, the Skidmore paper did get incredible social media engagement, unfortunately. Hilariously, Steve Kirsch then went on to do what Steve Kirsch does so hilariously and post the results of his own web “survey,” whose results were predictably one-sided:

A few days later, Kirsch tried to argue that the reasons cited for the retraction didn’t meet COPE standards:

Do any of these apply to the Skidmore paper? No. Not a single one.

In fact, Skidmore’s result was similar to data found by other researchers which puts to bed the first concern and the others aren’t even close to valid.

Which leads us to the inevitable conclusion that the paper was retracted unethically.

Was the Editor willing to discuss the retraction decision and answer questions? No.

Will the Editor reveal who objected to the paper and which of these items they cited? No, they keep that a secret!

I’ll reveal to Mr. Kirsch that I wrote an email to the editors expressing my concerns about the methodological flaws about the paper, mainly because (1) I’m not in the least bit embarrassed by it and (2) if Kirsch really does go through with his lawsuit the email will be found during discovery anyway. I will also mention that I highly doubt that I was anywhere near the only academic who did so. More importantly, at the time, I was also very disappointed that I never received a substantive response, just an acknowledgment from someone from “editorial support”—not even from an editor!—that my email had been received. I figured at the time that my concerns were probably not being seriously considered, much less addressed.

In any event, I listed all my concerns about the paper, including how I thought that it had been a “bait and switch” in which the stated primary aim was the “bait” used to get IRB approval for the study while the true primary aim was to come up with an inflated death toll. I also noted a working paper that Prof. Skidmore had published 11 months before that had used the same methodology of the retracted paper and was full of antivax talking points that I referred to as an “antivax ‘greatest hits’ compilation.” I also noted a definite conflict of interest in that this was a single-author, single funder study, and the funder is Catherine Austin Fitts, who appeared in a COVID conspiracy movie Planet Lockdown and has worked with antivaccine activist Robert F. Kennedy, Jr, as reported in The Washington Post. Of note, Prof. Skidmore also maintains a personal blog, Lighthouse Economics that is packed with antivaccine misinformation.

Basically, I wrote nothing more than what I had published on my not-so-secret other blog, suggesting that the paper should be retracted because:

- The methodology did not support the conclusions and was risibly substandard

- Of serious concerns about an undisclosed conflict of interest related to the funder of the study

- Of the likelihood that MSU’s IRB approved the survey instrument and recruitment methods for different endpoints than what they were ultimately used for, which, if true, would make this study unethical

All of these reasons to request retraction are consistent with COPE guidelines, and any one of them would, in my opinion

Yet, Mr. Kirsch and Prof. Skidmore’s allies portray this retraction as “censorship” and threaten lawsuits. I rather suspect it’s all performative. For one thing, note how Kirsch says he’ll support any author who wants to sue. This particular retracted paper was a single-author paper, with Prof. Skidmore as the sole author. If anyone were going to sue, it would have to be him. Given that discovery is a two-way street, I’d have to wonder if he really would like everything about the publication of this paper to be revealed, including all versions of the protocol, the IRB application, reviews, and approval. I rather suspect not, although I could be wrong.

The bottom line

Unfortunately, journal editors have traditionally been far more unwilling to retract bad, unethical, or fraudulent papers than they should be. While I can understand some of the reluctance, given that each retraction is an admission that they had screwed up and accepted a manuscript that should never have been published and that sometimes papers that are bad but were done honestly are not necessarily deserving of retraction. I can also understand concerns about legal ramifications. (I realize that by publicly acknowledging that I was one of the academics who wrote to the BMC Infectious Diseases editor to express concerns about the paper I might just have bought myself a deposition if Prof. Skidmore does decide to sue, but on the other hand his lawyers will see that email anyway if he does sue.) Journals need to do better despite all that because, as the study by Taros et al shows, retracted papers about COVID-19 have a malign and distorting effect on the medical literature. Going beyond the study, they often serve as clickbait that antivaxxers, pandemic minimizers, and those opposed to public health interventions use to spread fear, uncertainty, and doubt about medicine, science, and public health. More broadly, we as a scientific community have to do better as well by not citing retracted papers unless it is in the context of discussing the retraction.