The National Acupuncture Detoxification Association (NADA) teaches and promotes a standardized auricular acupuncture protocol, sometimes called “acudetox.” NADA claims acudetox

encourages community wellness . . . for behavioral health, including addictions, mental health, and disaster & emotional trauma.

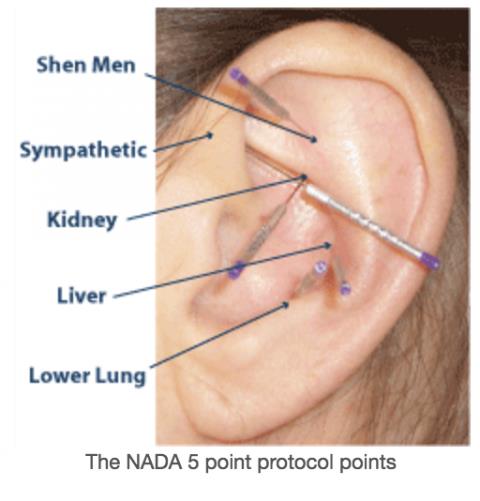

I do not know what “community wellness” is or how one measures whether wellness has been successfully “encouraged.” In any event, in the NADA protocol, acupuncture needles are inserted bilaterally into the auricle (outer portion) of the ear at a depth of 1-3 mm at five specific points (sympathetic, shen men, lung, liver, and kidney) and left in place for 45 minutes.

And:

Beyond the actual needling treatment, a key element of the protocol specifies qualities of behavior and attitude on the part of the clinician, consistent with what is known as the Spirit of NADA.

NADA claims there is

strong evidence for the effect of the NADA protocol in improving patient outcomes [in addiction treatment] in terms of program retention, reductions in cravings, anxiety, sleep disturbance and need for pharmaceuticals.

In support of these claims, NADA offers research in the form of Evidence for the NADA Ear Acupuncture Protocol: A Review of the Literature, an unpublished monograph available on its website. According to the Review, the “evidence base for the adjunctive use of the NADA protocol for addictions continues to grow” and that two recent studies “demonstrate that the NADA protocol in addition to standard care is significantly better than standard addictions care alone.” We’ll return to these claims shortly.

According to its website, NADA has trained more than 10,000 counselors, social workers, nurses, MDs, psychologists, acupuncturists, chiropractors, corrections officers, and others to use its protocol and over 1,000 addictions programs in the U.S. and Canada “now use acupuncture.” Graduates of their 70-hour program earn certificates which, in a number of states, entitle them to practice auricular acupuncture for addiction treatment. NADA also claims that over 25,000 providers worldwide have been trained and that the protocol is offered in 40 countries.

The practice of auricular acupuncture is governed by a patchwork of state laws with inconsistent provisions. In some, there is no specific law governing the use of auricular acupuncture. In others, statutes spell out who can be trained in auricular acupuncture (e.g., nurses, social workers), what they are called (e.g., “acupuncture detoxification technician,” “acudetox specialist”), and who must supervise them (e.g., acupuncturist, medical doctor). Some states incorporate NADA’s training standards without mentioning NADA; others specify NADA training. NADA actively lobbies for laws permitting those who are not licensed acupuncturists to perform the NADA protocol.

One source mentions French neurologist Paul Nogier and his “discovery” of a fetal homunculus on the human ear in discussing the use of auricular acupuncture in addiction treatment. In an apparently independent “discovery” (whose relationship, if any, to Nogier is unclear), in the 1970s, a Dr. H.L. Wen was investigating electro-acupuncture for analgesia in Hong Kong. Patients reported that their desire for heroin was eliminated after the electro-acupuncture treatment. (Heroin abuse was rampant in Hong Kong, hence the number of users scheduled for surgery.) Case studies, but no trials, of the procedure were published.

Dr. Michael O. Smith, who worked at a methadone treatment program at Lincoln Hospital in the South Bronx in New York City, was looking for alternatives to methadone and heard about Dr. Wen’s work in the 1970s. He originally used electro-acupuncture, but switched to auricular acupuncture at some point, which he apparently used as a primary, and not just adjunctive, treatment. He chose the five points based on traditional Chinese acupuncture maps supposedly “known to give the best results in treatment of drug dependence.” Smith reported great success anecdotally, but no clinical trials were done. At Lincoln, Smith expanded the use of auricular acupuncture from heroin addiction to crack cocaine and alcohol dependency. In 1985, Smith (who is still on the Board of Directors) and others formed NADA.

In 1989, Dade County, Florida started the nation’s first “drug court,” that is, a program to divert those charged with certain drug crimes to treatment. It incorporated acupuncture detoxification into its program. Other jurisdictions followed suit and one source claims it is used in 40% of drug courts. Yet, in 1991, the National Institute of Drug Abuse (NIDA) conducted a technical review of acupuncture for opiate dependence, noting that “very little methodologically solid work” had been done in the 1970s and 1980s. In a criticism reminiscent of one we often make on SBM, NIDA chastised the premature adoption of acupuncture treatment:

[A]cupuncture procedures have been accepted and expanded over the same period of time and are now used in the treatment of cocaine and alcohol dependence. While some studies have emerged that were experimentally and clinically reasonable, the consensus was that much fundamental work remains to be done and that after two decades of contemporary use in the field of addiction, there is no compelling evidence for the efficacy of acupuncture in the treatment of either opiate or cocaine dependence.

Does NADA’s evidence support the protocol?

In the twenty-five years since, there is still no compelling evidence, but you’d never know that from reading NADA’s Evidence for the NADA Ear Acupuncture Protocol: A Review of the Literature. (The Review is undated, but another source dates it as 2013.) The author, a Doctor of Oriental Medicine and a NADA Registered Trainer, reaches his positive conclusions about the NADA protocol by cherry-picking the evidence. (Unfortunately, so does a Bureau of Justice Assistance Drug Court Technical Assistance Project on the subject.) That fact, unfortunately, is lost on public policy makers. Just last month, in yet another example of Legislative Alchemy, the Governor of Rhode Island signed legislation allowing chemical dependency professionals to use “auricular acudetox” in their practices “in accordance with the NADA protocol.”

The Review also says that evidence supports the NADA protocol as an adjunctive treatment for nicotine addiction, behavioral health (e.g., PTSD), and for cancer and blood disorders, topics this post will not address.

The Review makes two claims for use of the NADA protocol for addictions:

- The prevalence and appropriateness of acupuncture for addictions is well established.

- The evidence base for the adjunctive use of the NADA protocol for addictions continues to grow.

Prevalence, of course, is not indicative of effectiveness. As for “appropriateness,” the Review says the Center for Substance Abuse Treatment, the UN, New Mexico and the U.S. Department of Defense/Veterans Affairs all include best practice guidelines “that address the value of acupuncture for chemical dependency.” This statement is true – they do mention acupuncture. But, the Center for Substance Abuse Treatment actually says there is no conclusive data. The UN’s Drug Dependence Treatment: Interventions for drug users in prison cites only one pilot study published in Medical Acupuncture. New Mexico’s prison reform task force report claims acupuncture is “very effective” but cherry picks the evidence in its brief review. The VA Clinical Practice Guideline is for PTSD, not substance abuse. In any event, as we know, the VA has a weakness for unproven CAM treatments and this document is no exception. David Gorski recently deconstructed the VA’s promotion of acupuncture, including for PTSD.

A review of the Review

Let’s turn, then, to the Review‘s claim that the evidence base “continues to grow” for the NADA protocol in treatment of heroin, alcohol and cocaine addictions. In support of his conclusion, the author cites eleven journal articles. Five of the studies reported in these articles were pilot studies, which do not evaluate safety, efficacy or effectiveness. (Bullock, Culliton; Bullock, Ulmen; Chang; Russell; Santasiero – I could not locate this article based on the citation given, but the title says it is a pilot study.) Significantly, the author fails to mention that two of the pilot studies were followed by a large randomized controlled study of auricular acupuncture for alcohol dependence, carried out by some of the same researchers, that did not confirm their results:

In this study, we extended the work of our early pilot studies . . . utilizing a more powerful design in an effort to further delineate the role of acupuncture in the treatment of alcoholism. . . In summary, our findings do not support the addition of acupuncture to conventional treatment in the treatment of alcoholism.

Of the remaining citations in support of the NADA’s claims, one (Bergdahl) simply described 15 patients’ “experiences” of the NADA protocol during post-acute withdrawal. Another (Janssen) was a feasibility study.

The rest do little to make up for the lack of evidence of effectiveness presented so far:

Avants: Participants receiving NADA protocol had significantly fewer positive urine samples over 8 weeks than 2 controls. No significant differences between the 3 treatment conditions in ratings of satisfaction with sessions, duration of treatment effects, or willingness to pay for future sessions. Comparisons between the 2 needle-insertion conditions disclosed no significant differences on ratings of pain. Relaxation controls reported significantly more relaxation effects after sessions than did patients assigned to either type of needle insertion. Practitioners unblinded, participants partially blinded, high dropout rate.

Carter: Prospective trial in a self-selected population of nonrandomized patients. “NADA acupuncture may help facilitate significant reduction in cravings, depression, anxiety, anger, body aches/headaches, concentration, and decreased energy.”

Schwartz: “[O]ur study is of the value of outpatient detox programs that utilize acupuncture; it is not of the contribution that acupuncture makes to the outcomes associated with these programs.”

Washburn: “Attrition was high for both groups, but subjects assigned to the standard treatment attended the acupuncture clinic more days and stayed in treatment longer than those assigned to the sham condition.”

On the other hand . . .

In addition to the large RCT that refuted the results of earlier pilot studies of auricular acupuncture, the NADA’s research monograph fails to cite other studies and reviews of the evidence that do not support the NADA protocol for addiction, either as a primary or adjunct treatment. This is even more inexplicable in light of the fact that what is described as a “bibliography of research” on the NADA website does list some of the omitted journal articles, although the list does not give any information about their conclusions. Thus, the existence of the studies was known, but they were ignored in the Review. In fact, there are so many studies and systematic reviews concluding that acupuncture, auricular acupuncture and/or the NADA protocol are not effective in the treatment of addiction, you could well find the repetition boring, but here we go:

“Efficacy of acupuncture for cocaine dependence: a systematic review and meta-analysis ,” published in 2005, concluded that the research does not support the use of auricular acupuncture for cocaine dependence.

A systematic review of acupuncture for opiate addiction, including auricular acupuncture, published the next year in the Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment found that

acupuncture treatment does not demonstrate the type of qualitative and quantitative research needed to validate its efficacy in the treatment of opiate-addicted (or cocaine-addicted) patients . . . [W]hen well-run methodologically sound studies are painstakingly administered, the placebo effect become apparent and the minimal efficacy of acupuncture in opiate addiction can be demonstrated.

A Cochrane Database Systematic Review, also published in 2006, concluded there is no evidence that auricular acupuncture is effective for cocaine dependence and that

[t]he widespread use of acupuncture is not based on sound evidence.

A 2012 systematic review of acupuncture studies, including auricular acupuncture, for attendance rate, craving scale, and opiate withdrawal symptoms said that, after 35 years of research by both Asian and Western scientists, the efficacy of acupuncture in the treatment of opiate addiction had not been established.

A 2009 systematic review came to the same conclusion for alcohol dependence.

A 2004 systematic review of the efficacy of the NADA protocol itself “could not confirm” it was effective for cocaine abuse.

A 2002 randomized controlled trial studying the NADA protocol for cocaine addiction, published in JAMA, concluded it was no more effective than sham needle insertion or a relaxation control in reducing cocaine use as either a stand-alone treatment or where patients were receiving only minimal concurrent psychosocial treatment, nor did acupuncture improve retention rates in the treatment program.

Fortunately, later trials with similarly negative results have begun to question the NADA protocol’s continued use. In 2008, a study concluded that auricular acupuncture had no effect upon withdrawal severity or craving when provided as an adjunct to a standard methadone detoxification regimen.

The results are consistent with the findings of other studies that failed to find any effect of acupuncture in the treatment of drug dependence. The failure to find any clinical gains from the adjunctive use of auricular acupuncture during detoxification from opiates raises concerns about the widespread acceptance of this intervention.

Another, published in 2011, was, according to the authors, the first randomized controlled trial to use objective measures in evaluating the efficacy of the NADA protocol for reducing anxiety in patients withdrawing from psychoactive substances.

The authors noted that

despite a lack of research evidence, the NADA protocol remains in use in more than 700 treatment facilities in the United States, as well as in approximately 30 countries worldwide. To date, more than 15,000 individuals have received training in the NADA protocol.

Their own randomized controlled single-blinded clinical trial, they said, added to the body of evidence refuting the NADA protocol’s utility. Thus,

Collectively, these findings are leading many substance abuse treatment agencies to question the appropriateness of the therapy.

However, having made its excellent points about the lack of evidence and the sensible pushback against using the NADA protocol, the article ends on this unfortunate note:

Evidence-based decision making tells us that evidence is only one part of the decision-making process (Sackett, Richardson, Rosenberg, & Haynes, 1997). Equally important to the clinical decision-making process are conclusions from clinical observation and patient values and perspectives. As such, it would be inappropriate to conclude that he NADA protocol is without value based on only one aspect of the decision-making process.

No, it wouldn’t. Sackett, et al., didn’t say the clinician should ignore the evidence in favor of uncontrolled clinical observations and misinformed patient choices, which is what the authors appear to suggest. They actually said:

The practice of evidence based medicine means integrating individual clinical expertise with the best available external clinical evidence from systematic research.

The “best available external clinical evidence from systematic research” tells us that the NADA protocol is ineffective.

Finally, a panel of 75 addictions experts rated 65 addiction treatments to establish a professional consensus on discredited treatments, rating them on a 1 (“not at all discredited”) to 5 (“certainly discredited”) scale. The results, published in the Journal of Addiction Medicine in 2010, scored auricular acupuncture for cocaine addiction at 3.88, 4 being “probably discredited.” Acupuncture for alcohol dependence and cocaine dependence scored 3.5 and 3.7, respectively.

Conclusion: Acupuncture does not treat addiction

The NADA protocol was conceived and initially used based on pre-scientific myths about human functioning and anecdotal evidence. As is the case with acupuncture studies in general, more rigorous trials failed to support the initial weak evidence in its favor, either as a primary or adjunctive treatment for addiction itself or related symptoms. It is an elaborate placebo masquerading as an effective adjunct treatment for addiction. Yet, NADA continues to push its protocol by cherry-picking the evidence and continues to teach it to addiction treatment professionals and lobby for it in state legislatures. Via the magic of quackademic medicine, Yale has established a NADA training program for its psychiatry addictions fellows, despite its admitted lack of evidence, resulting in physicians “integrating acupuncture into their current practice.”

Not content with its unsupported claims for use as an adjunct to addiction treatment, NADA has been seized by a bad case of mission creep and branched out into promoting the protocol for behavioral disorders, such as PTSD, disaster relief/humanitarian aid, and “adjunctive care and self-help support” for cancer and blood disorders. That, of course, is the beauty of alternative/complementary/integrative medicine. Evidence doesn’t matter.