It is disheartening that we have to return to pseudosciences that have been debunked decades ago, because they continue to linger despite being eviscerated by scientific scrutiny. Belief systems and myths have incredible cultural inertia, and they are difficult to eradicate completely. That is why belief in astrology, while in the minority, persists.

Professions, however, should be different. A healing profession should be held to a certain minimum standard of care, and that standard should be based upon something real, which means that scientific evidence needs to be brought to bear. Professionals are not excused for persisting in false beliefs that have long been discredited.

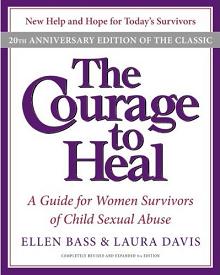

The 1980s saw the peak of an idea that was never based on science, the notion that people can suppress memories of traumatic events, and those repressed memories can manifest as seemingly unconnected mental health issues, such as anxiety or eating disorders. The idea was popularized mostly by the book The Courage to Heal (the 20th anniversary edition was published in 2008), in which the authors took the position that clients, especially women, who have any problem should be encouraged to recover memories of abuse, and if such memories can be dredged up, they are real.

The notion of repressed memories led in part to the satanic panic of the 1980s, and many of those subjected to recovering techniques not only “remembered” being abused, but being part of satanic ritual abuse.

Recovered memory syndrome was a massive failure on the part of the mental health profession. The ideas, which were extraordinary, were never empirically demonstrated. Further, basic questions were insufficiently asked – is there any empirical evidence to support the amazing events emerging from therapy, for example? Is it possible that the recovered memories are an artifact of therapy and are not real?

Now, with three decades of hindsight, we can say a few things with a high degree of confidence. Recovered memory syndrome is either entirely or mostly a fiction. People do not repress memories of extreme trauma. Further, as Elizabeth Loftus pointed out, memories are constructed and malleable things. Also, independent investigations by the FBI, other law enforcement agencies and scholars never found any evidence of the satanic ritual abuse, murders, and other atrocities emerging in recovered memory sessions. The events never happened.

What emerged from the entire sad episode was an increased understanding of what is now called false memory syndrome, the construction of entirely false memories. This was accomplished through guided imagery, hypnosis, suggestion, and group pressure. These techniques violate basic rules of investigation. Every medical student learns not to lead their patient or put words in their mouth. This is especially true if the patient is vulnerable and confused.

While there is some legitimate controversy over whether or not it is even possible to repress such memories and accurately recall them later, there is no question that the massive repressed memory industry of the 1980s and 90s was not evidence-based and was essentially an industry of creating false memory syndrome. The fact that a controversial idea was put into practice so widely, despite the risks to patients and their families, indicates, in my opinion, a systemic lack of self-regulation within the mental health profession.

More disappointing is the fact that recovered memory therapy is still ongoing today, which is completely unacceptable. Even if you wish to adhere to the minority opinion among memory experts that repressed memory is possible, the evidence does not justify putting it into practice. The potential for harm is more than sufficient to suspend the practice pending further evidence (if you wish to be a holdout).

An analogous situation in the health profession would result in a thorough banning of the procedure until further evidence demonstrates a favorable risk vs benefit ratio. If, for example, a drug on the market is found to cause liver failure, it is often immediately pulled until further evidence shows that it is safe, or at least can be used safely in some situations.

Loftus recently conducted a survey on persistent beliefs in recovered memory and found:

Even though skepticism toward the idea has increased among general respondents, more than 80 percent of them still hold fast to the idea that traumatic memories can be repressed, and 70 percent believe memories can be accurately retrieved by therapy. More troublingly, over 43 percent of practicing clinical psychologists think it is possible to retrieve repressed memories. Among Internal Family Systems therapists, 66 percent believe it is possible.

A recent article demonstrates that recovered memory therapy still has the potential to completely destroy innocent lives. The article details the case of a father accused of long-term sexual abuse by his daughter who “recovered” the memories while being treated for depression and an eating disorder. He was eventually cleared, but only after his life was shattered. Child Protective Services actually took the “recovered memory” claims seriously, which is yet another failure.

Conclusion

The evidence is fairly overwhelming that the majority (perhaps all) of the cases of alleged recovered memory of abuse are in reality cases of false memory syndrome produced by gross therapy malpractice, utilizing disproved techniques that violate basic rules of investigation and flagrantly disregard the potential for harm.

The myth of repressed memories is likely one that we will have to debunk over and over, for each new generation.

Perhaps more importantly, the persistence of this myth and practice among some therapists indicates that the profession has a serious problem with self-regulation and maintaining a reasonable evidence-based standard of care.