Yesterday, I spiffed up a post that some of you might have seen, describing how a particular medical conspiracy theory has dire consequences in terms of promoting non-science-based medical policy. Specifically, I referred to how the myth that there are all sorts of “cures” for deadly and even terminal diseases that are being kept from you by an overweening fascistic FDA’s insistence on its approval process is an important driving force behind ill-advised “right to try” legislation that’s passed in four states and likely to pass in Arizona by referendum tomorrow. I’m not exaggerating, either. If you have the stomach to delve into the deeper, darker recesses of alternative medicine and conspiracy theory websites, you’ll find words far worse than that used to describe the FDA, such as this little gem from everyone’s favorite über-quack Mike Adams basically portraying the FDA as Adolf Hitler. Even more “mainstream” advocates, such as Reason.com’s Ronald Bailey and Nick Gillespie, are not above using a version of this myth stripped of the worst of its conspiracy mongering for public consumption, claiming that the FDA is killing you.

Unfortunately, this sort of medical conspiracy theory is very common. Like all conspiracy theories, medical conspiracy theories tend to involve “someone” hiding something from the public. I like to refer to this as the fallacy of “secret knowledge.” That “someone” hiding the “secret knowledge” is usually the government, big pharma, or other ill-defined nefarious forces. The “secret knowledge” being hidden comes invariably in one of two flavors. Either “they” are hiding cures for all sorts of diseases that conventional medicine can’t cure, or “they” are hiding evidence of harm due to something in medicine. Although examples of the former are common, such as the “hidden cure for cancer,” it is examples of the latter that seem to be even more common, in particular the myth that vaccines cause autism and all sorts of diseases and conditions, that genetically modified organisms (GMOs) are dangerous, or that radiation from cell phones causes cancer. In these latter examples, invariably the motivation is either financial (big pharma profits), ideological (control, although descriptions of how hiding this knowledge results in control are often sketchy at best), or even some seriously out there claims, such as the sometimes invoked story about how mass vaccination programs are about “population control” or even “depopulation.” Either way, “The Truth” needs to be hidden from the population, lest they panic and revolt.

Indeed, in the case of the antivaccine movement, the belief that the CDC is “hiding” the true harms of vaccines (such as that they can cause autism) has been called the central conspiracy theory of the movement. It’s not surprising, then, that antivaccinationists have tried to claim that vaccines are responsible for the initial Ebola outbreaks in West Africa. These conspiracy theories have profound effects dealing with health emergencies. In particular, the idea that the CDC is “hiding” something can undermine trust and facilitate the spread of misinformation. That’s just what happened last week.

The CDC “admits”…nothing new!

Just last week, there was an example of just how pernicious these beliefs can be in the middle of an outbreak of a disease as deadly as Ebola. This example came in the form of a news story/meme that popped up first in the fever swamps of conspiracy and quackery sites like NaturalNews.com and then found its way into more “mainstream” outlets. Perhaps the reason that the story gained traction last week is that it happened as news stories were circulating about a Maine nurse named Kaci Hickox, who had treated Ebola patients in West Africa. When she returned a week and a half ago, arriving first in Newark, she was quarantined in appalling conditions in a tent with no heat, even though she showed no symptoms other than a one-time low grade fever on forehead scanning on arrival, has been completely asymptomatic since, and ultimately tested negative for Ebola. Ultimately, having been accused of playing politics with fear of Ebola (which he clearly was), NJ Governor Chris Christie was forced to relent, and Hickox went home to Maine, where a similar scenario played out, this time with Maine Governor Paul R. LePage, in the heat of a tight re-election race, equally shamelessly played for politics by pushing for an in-home quarantine for the full 21-day incubation period, even though it was not medically indicated. Meanwhile, the online opprobrium against Hickox, where demands that she be arrested were common, was depressing to behold. Apparently we’ve learned nothing since the Black Plague. At least then there was the excuse that people had little or no idea what caused the plague.

I had to admire Hickox in a way for defying Maine’s governor and ignoring the quarantine order, but on the other hand I was concerned that there is such a thing as being too bold in this case and questioned whether so blatantly flouting the governor by going out in public was particularly wise. I say that not because I thought that her quarantine was medically indicated, but more because I was worried that someone, out of fear of Ebola, would kill her if he saw her out in public. In any case, ultimately, Judge Charles C. LaVerdiere, the chief judge for the Maine District Courts, struck down the quarantine as not being reasonably based in science and instead ordered the much more reasonable and science-based condition that Hickox submit to daily monitoring for symptoms, to coordinate her travel with public health officials, and to notify them immediately if symptoms appear, stating that she “currently does not show symptoms of Ebola and is therefore not infectious.”

Into this background started appearing stories, first in places like NaturalNews.com, then in the New York Post, claiming that the CDC “knew” or “admitted” that Ebola could be spread by air. Part of the conspiracy of “secret knowledge” invariably involves that knowledge being inadvertently revealed somehow, either through an inadvertent admission or some other way. Clearly, the “secret knowledge” here was that, contrary to what scientists have been saying all along that Ebola is spread by contact with infected bodily fluids in much the same way HIV and hepatitis B are, in reality you could catch it just by being in the same room as someone with Ebola. This is the sort of story I’m talking about in the NY POST, “CDC admits droplets from a sneeze could spread Ebola“:

Ebola is a lot easier to catch than health officials have admitted — and can be contracted by contact with a doorknob contaminated by a sneeze from an infected person an hour or more before, experts told The Post Tuesday.

“If you are sniffling and sneezing, you produce microorganisms that can get on stuff in a room. If people touch them, they could be” infected, said Dr. Meryl Nass, of the Institute for Public Accuracy in Washington, DC.

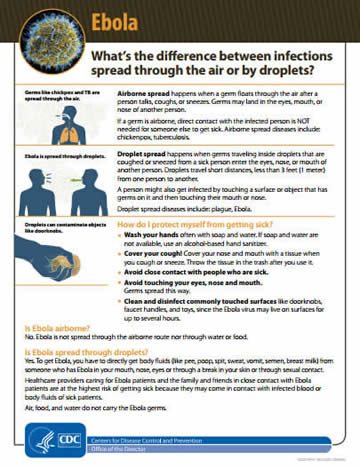

Nass pointed to a poster the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention quietly released on its Web site saying the deadly virus can be spread through “droplets.”

“Droplet spread happens when germs traveling inside droplets that are coughed or sneezed from a sick person enter the eyes, nose or mouth of another person,” the poster states.

Nass slammed the contradiction.

“The CDC said it doesn’t spread at all by air, then Friday they came out with this poster,” she said. “They admit that these particles or droplets may land on objects such as doorknobs and that Ebola can be transmitted that way.”

First off, let’s just say that Dr. Nass is not exactly a reliable source. For example, she’s been known to show up on quack websites like Mercola.com spouting antivaccine tropes, to write a letter asking for help to the antivaccine website Vaccination News, and to write a great deal about mass vaccination programs, particularly anthrax vaccines in the military, viewing it as a cause of Gulf War syndrome. Indeed, she has her very own page on that granddaddy of conspiracy sites, Whale.to and did this video for Gary Null:

It’s a video full of conspiracy mongering against the CDC, insinuations that Gardasil is killing girls, and claims that recent litigation “reduced” the ability of victims of vaccine injury to claim compensation. Making a newbie (or antivaccine) mistake, she takes claims made to the Vaccine Adverse Effects Reporting System (VAERS) at face value, even though it’s been described many times why VAERS is not a good measure of the true frequency of adverse events related to vaccines and is heavily influenced by litigation and publicity. Regular readers will recognize the misinformation and tropes, so much so that I had a hard time listening to the entire 15 minutes of the video.

But what about the poster to which Dr. Nass pointed as evidence that the CDC was “admitting” that Ebola could be spread through the air? Clearly, she’s been getting her information from people like Mike Adams and sites like NaturalNews.com, where Adams ran a story on Friday entitled “Schizophrenic CDC pulls document admitting Ebola can spread via sneezes and doorknobs; see the original here“:

Just days after admitted it lied about how Ebola spreads and finally admitting the virus can spread through aerosolized particles propelled via sneezing or coughing, the CDC yanked its document off the web.

It replaced it with a new PDF that’s almost entirely empty, except for the statement “Fact sheet is being updated and is currently unavailable.” You can see that file at this CDC link.

As the editor of Natural News, I anticipated the CDC doing this, so I saved off a copy of the original PDF on Natural News servers, which you can access at the following link: http://www.naturalnews.com/files/infections-…

“Ebola is spread through droplets” – admitted but now scrubbed

As you can see in the original document the CDC has now buried, it admitted “Ebola is spread through droplets,” and stated “Droplet spread happens when germs traveling inside droplets that are coughed or sneezed from a sick person enter the eyes, nose, or mouth of another person.”

The document also stated “Droplets can contaminate objects like doorknobs” and explained “A person might also get infected by touching a surface or object that has germs on it and then touching their mouth or nose.”

This is a classic example of confusing the colloquial definition of a term with the scientific definition of a term, in much the same way creationists think that a scientific theory is just a “hunch” or a “guess” because that’s what most people mean when they say theory. To explain what is really going on here, let’s look at the actual original poster, taken from NaturalNews.com and other websites that have “saved” it to prevent the CDC from going back on what it said (click for full PDF):

Then there’s the changed poster, dated November 1. Adams claims that the CDC link went to an empty document, but in reality the document is there. Perhaps he clicked on it while the document was being revised. Either way, here it is (click for full PDF):

On the surface, this sounds as though Nass and Adams might have a point, that Ebola can be spread by air, but they don’t. Their contention rests on the colloquial idea of what it means to be spread through the air. If someone sneezes a wet sneeze right in someone else’s face, to the average lay person that suggests that the droplets can be spread through the air. However, that’s not what epidemiologists and infectious disease specialists mean when they state that a disease can be spread through the air. Similarly, when they say that disease can be spread through “droplets,” they are not saying that the disease is “airborne” or can be spread through the air. To help explain the difference, I’m going to steal shamelessly from a post by colleague of mine (well, posts actually), Tara Smith, as well as posts to which she’s linked, such as one from Virology Down Under and this one from Pathogen Perspectives. You don’t need to click those links if you don’t want to, but I highly recommend that you do because they are excellent discussions.

To understand where Nass and Adams go wrong, it’s necessary to understand what infectious disease experts mean when they speak of droplets. As Heather Lander explains, bodily secretions that make it into the air from various orifices are called “droplets” and classified based on their size and the distance they can travel. The smaller the droplet, the longer it can stay suspended in the air and the farther it can travel. Not coincidently, the smaller the droplet, the deeper into the respiratory tract it can travel upon inhalation. Now here’s where this is relevant:

Teeny-tiny droplets (less than 5 microns) are generally referred to as “aerosols” and can be generated by a cough, a sneeze, exhaling, talking, vomiting, diarrhea, passing gas etc. Aerosols can also be generated mechanically by things like flushing a toilet, mopping, or rinsing out a bloody wash cloth. When aerosols are infectious, they transmit disease when they are inhaled by an organism and its called “aerosol transmission”. When droplets are larger than 10 microns they are called “large-droplets” and if infectious, they transmit disease by inhalation if the organism being infected is close enough to inhale the particles before they settle out of the air. They can also transmit virus if someone gets showered with droplets from, for example, a sneeze, or touching a droplet that is on the surface of an object(fomite) or someone’s skin and it’s called “large-droplet transmission”.

If you want to get more specific, this article will do it for you. Basically, by definition, aerosols are suspensions in the air small enough that they remain airborne for prolonged periods of time because of their low settling density. The article reports that for spherical particles of unit density, settling times for a 3 meter fall are 10 seconds for 100 μm, 4 minutes for 20 μm, 17 minutes for 10 μm, 62 minutes for 5 μm. Particles with a diameter less than 3 μm in essence do not settle. So for a disease to be truly airborne, it has to produce aerosols that hang in the air for a long time, such that prolonged contact (or even any direct contact at all) with the infected individual isn’t necessary for disease transmission. Also affecting this equation is how far these tiny particles can get into the lung. Particles greater than 6 μm tend to be trapped in the upper respiratory tract, while essentially no deposition of particles into the lower respiratory tract occurs for particles greater than 20 μm. To sum it up, a good rule of thumb is that particles in the micron or submicron range will behave as aerosols and particles greater than 10 to 20 μm will settle rapidly, won’t be deposited in the lower respiratory tract, and are called large droplets.

It’s a bit more complicated than that, too:

Whether propelled by sneezing, coughing, talking, splashing, flushing or some other process, aerosols (an over-arching term) include a range of particle sizes. Those droplets larger than 5-10 millionths of a meter (a micron [µm]; about 1/10 the width of a human hair), fall to the ground within seconds or impact on another surface, without evaporating (see Figure). The smaller droplets that remain suspended in the air evaporate very quickly (< 1/10 sec in dry air), leaving behind particles consisting of proteins, salts and other things left after the water is removed, including suspended viruses and bacteria. These leftovers, which may be more like a gel, depending on the humidity, are called droplet nuclei. They can remain airborne for hours and, if unimpeded, travel wherever the wind blows them. Coughs, sneezes and toilet flushes generate both droplets and droplet nuclei. Droplets smaller than 5-10µm almost always dry fast enough to form droplet nuclei without falling to the ground, and it is usual for scientists to refer to these as being in the airborne size range. It is only the droplet nuclei that are capable of riding the air currents through a hospital, shopping centre or office building.

This applies to basically all infectious diseases. Now, here’s where the confusion leading to articles like the NY POST article comes from. When infectious disease experts say that a virus is “airborne,” they have a very specific meaning. What they are saying is that the virus is capable of aerosol transmission via inhalation, even when not in close proximity to the source of the aerosol. In other words, if someone with measles (a very highly infectious virus that can be transmitted through the air), coughs up droplets in a room and then leaves the room and then you enter the room, you can breathe in the measles aerosol and will be very likely to contract measles if you haven’t been vaccinated.

The case is different for Ebola virus. As described and documented here, here, and here, for whatever reason, under as natural conditions, airborne droplet nuclei (the very tiniest droplets, the ones that can stay airborne indefinitely or for long periods of time) containing Ebola are not infectious. Whether it’s because the virus doesn’t like being dried down or primates don’t produce enough virus in saliva and mucus coughed up is not clear, but as described by VDU, there may be some Ebola virus in droplet nuclei – but it has never been shown to cause disease, even when that route has been specifically looked for in the same household as a cause of Ebola. Consequently, although Ebola virus-containing fluids are definitely infectious and can transmit Ebola virus disease, they are not considered airborne. Indeed, if Ebola were airborne, the casualties in this latest outbreak would have been far, far higher than the already high numbers we are seeing.

Now that you know this terminology, you should be able to see that there is nothing “nefarious” in either the first or second CDC poster, nor is there any “admission” that Ebola can be transmitted by air. The CDC has been consistent in stating that Ebola can be transmitted by droplets; it’s just that what is meant by that was not well understood. Perhaps that’s why the CDC decided to update the poster, to try to address the misunderstandings. As Tara Smith points out, it appears that the CDC just did a minor redesign of the poster, making some minor wording changes. The old poster stated that Ebola is not transmitted via the airborne route, and the new poster says the same thing. The original poster states that “if a germ is airborne, direct contact with the infected person is NOT needed for someone else to get sick,” in contrast to droplet transmission, which “happens when germs traveling inside droplets that are coughed or sneezed from a sick person enter the eyes, nose, or mouth of another person. Droplets travel short distances, less than 3 feet (1 meter) from one person to another.” The new poster states, “To get Ebola, you have to directly get body fluids (blood, diarrhea, sweat, vomit, urine, semen, breast milk) from someone who is sick with Ebola in your mouth, nose, eyes or through a break in your skin or through sexual contact.”

To repeat (because it’s so important), in other words, droplet transmission is not the same thing as airborne transmission. Airborne transmission can occur in places where the infected patient has been, even if it were hours ago, while droplet transmission requires being close to the infected patient. Yes, if an Ebola patient projectile vomits on you or bleeds on you, you will have Ebola virus on you that could infect you. Contrary to something like measles, just walking into an area of a building where an Ebola patient has passed through before is not going to result in your catching Ebola. Droplet transmission is still direct contact.

Finally, the NY POST and NaturalNews.com articles conflate droplet transmission with transmission by fomites (objects on which infected fluids wind up). Fomite transmission, however, is not thought to be a major source of Ebola transmission. As Smith puts it, it’s theoretically possible, but the object would have to be “heavily contaminated by a person late in the disease.”

How conspiracy theories harm

I can picture what some of you might be thinking: That’s mighty confusing. Some people would likely be confused even if Mike Adams weren’t spreading misinformation with an eye to selling Pandemic Protection Kits for “natural biopreparedness” and news organizations weren’t treating the story in a sensationalistic fashion. While that’s probably true, think of how much more difficult it is for health authorities to explain these things in a way that lay people understand, given all the medical conspiracy theories out there. For instance, as discussed by Steve and others a recent survey/study in JAMA Internal Medicine , 69% of respondents had heard the myth that the CDC and doctors know that vaccines cause autism and other neurological disorders; 20% agree; and 36% are neutral, neither agreeing nor disagreeing. That means two thirds of the population has heard this myth and over half don’t disagree with it. Similar numbers for the myth that the FDA is deliberately preventing people from getting natural cures for cancer and other diseases are 63% heard before; 37% agreeing; and 31% neutral. This means that well over half of the population don’t disagree that the FDA is trying to keep “natural cures” for cancer away from the population.

Is it any surprise that a population with such a high prevalence of belief in ideas that the CDC and FDA are hiding The Truth about vaccines and natural cures from the people and a high level of distrust in health authorities would be far more likely to latch onto the sort of fear mongering that people like Adams and Nass provide? When it comes to trying to explain complex concepts such as the difference between droplet and airborne transmission of disease to people holding such views (or at least being open to such conspiracy theories), is it any wonder that they’re easily confused? Even if the CDC and other health authorities communicated perfectly and didn’t make occasional mistakes along the way (as all humans do), there would likely be confusion. Add belief in conspiracy theories in which the CDC is believed to be hiding something, and those mistakes become magnified—or even spun as evidence supporting the “cover up” postulated by the conspiracy theory. Every inconsistent message is jumped on. Every message containing erroneous information is viewed as undeniable proof of either malice or incompetence.

None of this excuses conspiracy cranks like Mike Adams for spreading misinformation about Ebola in the first place. Indeed, the existence of cranks like Adams cynically spreading misinformation and sensationalistic journalists spreading, well, sensationalism mandate a response. However, even in the absence of cranks, there would likely be some confusion, given that lay people (and even most doctors) are not fully familiar with these definitions. Adams and Nass play on this ignorance to stoke fear, uncertainty, and doubt about the CDC.

Even the bloggers at Virology Down Under admit how hard it is, even under ideal circumstances, to communicate science-based information about Ebola transmission. First, they point out that, although airborne transmission has been engineered to occur in the laboratory using idealized conditions and very high amounts of virus, there is no evidence that it has ever occurred outside of a laboratory. They then discuss “messaging the masses”:

Leaving aside other issues around acquiring a rare disease like Ebola when outside of the current outbreak region, the case definitions and risk assessments have raised confusion. There are questions around how otherwise apparently well-protected healthcare workers in West Africa are acquiring an EBOV. For a virus described as spreading only through direct contact, recommendations for the use of masks, implying airborne spread to many, fuel such questions. In fact, face protection is recommended to prevent infectious droplets landing on vulnerable membranes (mouth and eyes).

It’s important to pass a message that is correct, but also to ensure distrust does not result from a public reading apparently contradictory literature. Such distrust and real concern have been rampant among a hyperactive #ebola social media. Simple, clear phrases like “ebolaviruses cannot be caught from around a corner” (h/t @Epidemino), may help uncomplicate the communication lines. And it works on Twitter.

In another post, virologist Ian MacKay has even solicited ideas for better ways to communicate these concepts to the general public in an accurate, but clear and understandable, fashion:

So the problem is trying to define a name for that other process that can simply and clearly describe infectious disease transmission of viruses & bacteria that are propelled from/by the sick person, across the gap between them and an uninfected person, measurably infecting the recipient. The name should make clear that it is a different process to the one that sees a person get sick by inhaling infectious viruses or bacteria held aloft by the air, in a cloud, made by a previously ill person, that has been hanging around for perhaps an hour or more. That one is an airborne route of transmission.

It is an excellent question. Not being a virologist or infectious disease expert, I’m not sure I have a good answer. I do know, however, that that answer must include language that can be used to counter the pernicious effects of the widespread belief in medical conspiracy theories. Absent such conspiracy theories, it would be hard to imagine why the CDC (or any other governmental authority) would want to hide evidence of airborne transmission, just as it would be hard to imagine any reason why the FDA would want to hide “natural cures” or the CDC hide harmful effects of vaccines and keep vaccinating. With such conspiracy theories as prevalent as they are, the jobs of Mike Adams and those like him are made much easier.