Fabrizio Benedetti is professor of physiology and neuroscience at the University of Turin Medical School in Turin in Italy, who is best known as a researcher studying placebo effects. In fact, arguably Benedetti is the most famous and influential researcher focusing on placebo studies. Indeed, we’ve mentioned him multiple times here on SBM over the years, with, for example, Harriet Hall discussing an interview on placebos that Benedetti did, with a followup on the ethical issues the use of placeboes engenders as well as the misinterpretation of his research by a journalist. His work has been used by purveyors of pseudoscientific medicine for at least as long as I can remember writing about pseudoscientific medicine, which means close to two decades. So it was with great interest that I was made aware by multiple people of a commentary written by Benedetti in Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics entitled “The Dangerous Side of Placebo Research: Is Hard Science Boosting Pseudoscience?” In it, Benedetti laments something that we’ve been lamenting ever since this blog started, namely how quacks are co-opting placebo research to justify their quackery. While I was happy to see a someone as renowned as Benedetti finally notice this and become disturbed enough about it to use his considerable cachet to publicize this problem, on the other hand I can’t help but be a bit frustrated that it’s taken him this long to speak out this way on the record in the peer-reviewed medical literature. (He’s also published in a quack acupuncture journal; he is not entirely innocent of himself promoting what Steve Novella has described as the placebo narrative.)

Of course, we here at SBM have described how quacks co-opt studies on placebo effects to justify their quackery. Indeed, we’ve observed many times that, as more and more rigorous scientific studies have shown that, for example, homeopathy has no effects distinguishable from nonspecific placebo effects, some homeopaths have switched from arguing that homeopathy has actual physiological effects that positively impact disease and its symptoms to arguing that the mechanism through which homeopathy “works” are placebo effects, which are rebranded in quack parlance as “powerful mind-body” effects or the power of positive thinking. Of course, as you will see and as Benedetti emphasizes, placeboes do not heal and do not produce more than transient effects on symptoms without affecting the overall course of the illness. They can’t cure cancer and do not affect the respiratory pathology of asthma. Worse, there is no such thing as placebo effects without deception, as we have repeated here many times, the attempts of acupuncture maven Ted Kaptchuk to “prove” otherwise notwithstanding, making the ethics of placebo use highly problematic at best. We also like to emphasize, as Benedetti himself does, that there is no single “placebo” effect, but rather placebo effects, which range from expectancy effects, to observation and reporting effects, to observer bias, and several others, making the whole topic very complex and often misunderstood.

Also, Benedetti gets on my nerves a little bit in that he makes placebo research sound far more wonderful and promising than it is. We see this in his introduction, where he goes on and on about how the “hard science” is validating placebo effects, even citing two of Kaptchuk’s articles on “open label placeboes without deception” favorably. I must admit that I did a little facepalm when I perused the reference list and saw that. However, he starts to right himself soon enough:

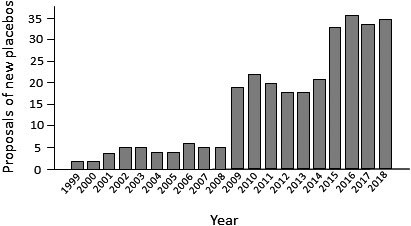

Although this is wonderful news for science, this may not be the case for society. The number of nonmedical organizations and healers that rely on this hard science, and actually justify their odd and bizarre procedures, has increased over the past few years. The main claim is that any procedure boosting patients’ expectations, which represent the main mediator of placebo effects, is acceptable because it can activate the same biochemical pathways and neural networks that have been made credible by hard science. Our department has witnessed an alarming increase in proposals from quacks and charlatans who devised new placebos which, they aver, may have powerful effects on those mechanisms so much emphasized by hard science (Figure 1). The first bunch of proposals our department received started in 1999, and they amount to 298 until the end of 2018, with an increase over time. In Figure 1, the sharp increase in 2009 is attributable to an article that appeared in the New England Journal of Medicine,9 asserting that ours was the foremost laboratory in the world studying placebos, which I believe may have had a great impact on the quackery community. It can be seen that a second sharp increase occurred in 2015, which can be attributed to the publication of this information in Wikipedia,10 which surely spread these concepts in the layman.

And here’s the figure:

Benedetti appears to be correct. There was a big increase in proposals to him in 2009, which does correspond to the publication of his NEJM article. I suppose it could have been something else but it seems reasonable enough that the increase of his fame as the premier placebo researcher in the world as the result of a publication in such a high impact journal would lead to quacks contacting him. He’s also correct. Quacks are glomming on to every new scientific finding with respect to placeboes and placebo effects:

The crucial point here is that when hard science started investigating placebo effects, it unconsciously produced a shift in quackery thinking. In fact, charlatans are becoming more and more aware that their bizarre interventions could work through a placebo effect. Indeed, whereas hard science has so far denied any scientific basis for nonconventional therapies, now the very same hard science certifies that the placebo effect has scientific grounds. Therefore, quacks are no longer interested in showing that their pseudo-interventions work; rather, they justify their use on the basis of the possibility that these bizarre interventions may induce strong placebo effects.

Which is what we’ve been saying for years, as I pointed out above. Indeed, sometimes the claims for placebo effects can include amusing hyperbole, such as when Robert Schiffman wrote, apparently with a straight face, that placebo effects are not only scientific, but they’re proof that God exists. I can’t resist quoting this little snippet from his article:

The placebo effect is arguably the most underrated discovery of modern medicine. Replace “just the placebo effect” with “the amazing placebo effect,” “the mind boggling placebo effect.” To my way of thinking, the very existence of this mysterious effect proves that God exists. That’s right, you can find evidence for the foundational truths taught by religion in virtually every double blind medical research study!

Then of course, there’s Deepak Chopra, who is all over placebo effects as “evidence” of “powerful mind-body healing” or “how the mind can heal the body“:

The placebo effect is real medicine, because it triggers the body’s healing system. One could argue that this is the best medicine, in fact, since: a. drugs do not trigger the healing system and b. the placebo effect has no side effects. Staying well means that the body is taking care of itself – and you – through a feedback loop of chemical messages. Circulating throughout the bloodstream, lymphatic system, and central nervous system, chemical messages are crucial to the healing system, because they keep every cell in communication with every other.

Then there’s Joe Mercola:

Your beliefs are energy fields, and they are working to promote either health or disease in your body right now. Which one is up to you.

When it comes to the ability of your mind to heal you, there are NO limitations. The sky is the limit.

And Andre Evans:

In clinical studies where patients are given placebos, they often will respond positively to them due to the expectation that they are receiving some form of beneficial medicine. Although not talking about placebo sugar pills specifically, this kind of self-treatment can be seen in one case where a woman’s own thoughts made her lose nearly 112 pounds.

Evans concludes:

If you believe that your illness is getting worse, it will probably get worse. If you believe that your treatment is helping you, you could actually cause massive self-healing to occur. Assuming a disposition will automatically prejudice your mind, and therefore cause your body to react either positively or negatively.

I’ve likened this view of placebo effects to the New Age belief system known as The Secret, which posits that if you only want something badly enough the universe will manifest it to you and it can be yours. Indeed, placebo effects are a major aspect of what I like to call the central dogma of alternative/complementary/integrative medicine, in essence, that wishing makes it so. It’s therefore no surprise to those of us who have followed the topics of quackery, CAM, and integrative medicine over the years that quacks immediately embrace any placebo research that they can portray as “proving” the power of the mind to heal the body and that whatever woo they are peddling “works” through placebo effects.

Benedetti notes with alarm the number of conditions for which quacks are advocating placebo medicine, including cancer, infectious diseases, central nervous system disorders like Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases, infertility (and to prevent pregnancy), and more. Here’s where we get to the meat of Benedetti’s article, in which he asks several questions and tries to answer them, including:

- What is the ethical limit to hand out placebos and to increase expectations?

- Can we accept every means available, whether a sugar pill or a bizarre concoction?

- What about those patients who trust bizarre rituals but not conventional drugs?

- Should their expectation-related brain mechanisms be activated by means of odd rituals?

Here’s the money paragraph:

Although a definitive solution to these ethical issues is surely difficult to find, I believe that at least two aspects need to be considered in depth: education and communication. We need to educate and communicate with patients and health professionals in order to make them better understand the placebo phenomenon and the related problems. A first point that should be emphasized is that placebos do not cure, but rather, they may sometimes improve quality of life. There is plenty of confusion on this point, and unfortunately, many claim that they can cure virtually all illnesses with placebos. Hard science tells us that placebos can reduce symptoms such as pain and muscle rigidity in Parkinson’s disease, yet the progression of the disease is not affected; for example, in Parkinson’s disease, neurons keep degenerating even though some symptoms can be reduced for a short time.4 The second point is related to the first. The type of disease is crucial, and we need to make people understand that pain is different from cancer and that anxiety differs from infectious diseases. The psychological component of some illnesses can indeed be modulated by placebos, but placebos cannot stop cancer growth, nor can they kill the bacteria of pneumonia. The third point is related to the difference between real placebo effects and spontaneous remissions. So far, hard science has studied the placebo effect within a time span of hours/days, thereby limiting our knowledge to short-lasting effects. Consequently, long-lasting effects can be often attributed to spontaneous remissions.

I’m not sure exactly what Benedetti meant by that last part about spontaneous remissions. The first time I read this, I thought that he was implying that placebo effects could cause spontaneous remissions, but a reread suggests that he meant that fortunate patients who chose quackery and were fortunate enough to have a spontaneous remission misattribute their good outcome to placebo effects. Of course, although I haven’t seen an example of a patient attributing remission of cancer to placebo effects, I certainly have seen (and documented) many cases of patients who underwent both conventional therapy and alternative medical treatments for, say, cancer and did well attribute their good fortune to the alternative medicine rather than the conventional “cut, burn, poison” (as quacks like to call it) therapy.

Benedetti is, of course, correct that placebos, as far as the “hard science” shows, do not heal or cure. Indeed, as we have argued, it’s certainly highly debatable whether they have any clinically meaningful effect at all. In clinical trials, after all, a placebo is nothing more than an inert treatment that serves as a surrogate for all the other confounding factors in patient treatments that can affect results: natural history of disease, physician and patient bias, regression to the mean, Hawthorne effect (observer bias), and more. It has even been argued that placebo effects are primarily an artifact of the clinical trial process. Indeed, a 2010 Cochrane review on placebo effects for all interventions notes that placebo effects vary from large to non-existent, even in well-conducted clinical trials and that these variations were partly explained by variations in how trials were conducted, the type of placebo used, and whether patients were informed that the trial involved placebo. The review also noted that it is “difficult to distinguish patient-reported effects of placebo from biased reporting”. Overall, the authors did not find that placebo interventions had important clinical effects in general. Similarly, in 2001, an analysis of clinical trials published in the New England Journal of Medicine comparing placebo with no treatment found “little evidence that placebos have powerful clinical effects” and had “no significant effects on objective or binary outcomes”. Basically, the preponderance of science suggests that placebo effects are probably mostly illusory, artifacts of clinical study design. I can’t help but note that even Benedetti himself does not advocate the use of placeboes in clinical practice yet, having stated that they are useful to study in clinical trials but that there are too many practical and ethical issues in clinical practice.

Still, it’s hard to disagree with Benedetti’s conclusion:

Overall, today the placebo phenomenon still remains a paradox and an effect not easy to handle. Besides the recent findings of hard science, many ethical concerns limit the implications and applications. We certainly need to pursue further research in this direction, yet the possible dangers of misuse and abuse should always be kept in mind. Unfortunately, quackery has today one more weapon on its side, which is paradoxically represented by the hard science–supported placebo mechanisms. This new “scientific quackery” can do a lot of damage; thus, we must be very cautious and vigilant as to how the findings of hard science are exploited. The study of the biology of these vulnerable aspects of mankind may unravel new mechanisms of how our brain works, but it may have a profound negative impact on our society as well. We cannot accept a world where expectations can be enhanced with any means and by anybody. This is a perspective that would surely be worrisome and dangerous. I believe that some reflections are necessary in order to avoid a regression of medicine to past times, in which quackery and shamanism were dominant. Unfortunately, the new knowledge about placebos by hard science is now backfiring on it. What we need to do is to stop for a while and reflect on what we are doing and how we want to move forward. A crucial question to answer is, Does placebo research boost pseudoscience?

The answer to that last question is certainly yes. I don’t need to “reflect” upon anything to know that, as I’ve been reflecting on placebo research for close to 15 years now. I would also point out that medicine is already, in at least one aspect, regressing to “past times, in which quackery and shamanism were dominant”. True, quackery and shamanism are not (yet) dominant again, but there is a whole specialty, “integrative medicine” or “integrative health,” that, while claiming to be evidence-based, nonetheless “integrates” pseudoscience and quackery such as acupuncture, “energy healing,” naturopathy, and even homeopathy, among many other forms of unscientific and pseudoscientific practices into its armamentarium of treatments, along with evidence-based lifestyle interventions, such as nutrition, exercise, and the like, thus making the quackery indistinguishable to the lay person from sensible, evidence-based recommendations. Worse, this specialty is becoming increasingly “respectable”, with institutes, divisions, and departments of integrative health popping up like kudzu in academic medical centers.

Of course, if an area of science increases our understanding of a scientific phenomenon and has arguably beneficial practical uses, it should be pursued. A lot of science can be misused (e.g., nuclear power, the scientific understanding of which is also used to create incredibly destructive weapons). The question to ask, I would argue, is not “Does placebo research boost pseudoscience?” The answer to that question is self-evidently yes. Rather, we should ask, “How can we mitigate the boosting of pseudoscience that placebo research inevitably produces?” Benedetti has some ideas on that topic, correctly pointing out that communication with patients is key, noting that “not only should we discuss and consider the positive effects of placebos and the impact they may have in clinical trials and medical practice, but we should also pay much of our attention to the negative counterpart, that is, the misuse and abuse by quacks, charlatans, shamans, and nonmedical organizations”.

We’ve been doing that for nearly 12 years now at SBM, and welcome Prof. Benedetti to the effort.

A world-renowned placebo researcher asks, “Does placebo research boost pseudoscience?”

Professor Fabrizio Benedetti is the most famous and almost certainly also the most influential researcher investigating the physiology of placebo effects. In a recent commentary, he asks whether placebo research is fueling quackery, as quacks co-opt its results. The answer to that question is certainly yes. A better question is: How do supporters of science counter the placebo narrative promoted by quacks, in which placebos represent the “power of the mind to heal the body”?