In 2013, and then again in 2017, I wrote about infant colic in the context of bogus claims by believers in chiropractic and acupuncture respectively. At the time, although considerably more hopeful and optimistic than the tired shell of a skeptic that I have become, I never imagined that the application of pseudomedical nonsense to colic would end because of my insightful analysis and commentary. And, as that younger me would have surely predicted, here we go again.

I went into extreme detail regarding the definitions, epidemiology, and pathophysiology of infant colic in my 2013 post, and then again in the 2017 post on acupuncture not working as a treatment. I invite readers to check those posts out if interested in more detail. I will briefly discuss infant colic in this post before delving into a recently published “single-blind randomized controlled trial” that serves as a prime example of how bias muddies the interpretation of study results and of the classic “more research is needed” tactic used so often in the world of irregular medicine.

What and why is infant colic?

(Going forward I will just call this mysterious entity colic, dropping the qualifier, because I’m confident that readers will not think that I’m writing about horses.)

Colic is, essentially, a reified concept forged into existence by our attempts to measure infant crying. All babies cry to some extent, with some crying more than others, and they always have. Modern humans in the past few decades have arbitrarily established a cutoff, a certain amount occurring for a certain number of days each week for a certain number of weeks, and labelled crying in excess of that cutoff as colic. This is of course almost entirely based on the subjective assessment of caregivers.

The entire endeavor, as well as our approach to colic in the medical community and in society at large, is more than a bit ridiculous. Thinking of colic as a real condition, and communicating that thought process to caregivers, engenders an environment where a treatment must exist and should be sought out. These assumptions often result in overdiagnosis of things like reflux disease, the treatments for which are rarely helpful and can be harmful in infants, and can increase caregiver anxiety when no specific explanation or treatment is offered.

I am of course not saying that infants who cry a lot, or seem to, never have an underlying medical condition. They absolutely sometimes do. I encourage caregivers to talk to their child’s primary care provider about their concerns, and those providers should perform a thoughtful evaluation. As I discussed in my previous posts, it is not unreasonable to sometimes recommend a structured trial of dairy avoidance or a specialized formula to rule out a milk protein allergy.

With the possible exception of milk protein allergy, babies labelled as colicky rarely have a problem that requires a medical or surgical intervention and the unexplained crying will almost always improve dramatically by 3-4 months of age, lending credence to the hypothesis that colic is a manifestation of a normal developmental process in the infant brain. I think that most colic ends up being diagnosed because of an imbalance in the child-caregiver dyad, a mismatch of infant temperament and caregiver tolerance of crying.

But the amount or nature of an infant’s crying is not really the metric that should be focused on. What matters most is how a caregiver, or caregivers, respond to any crying and how pediatric professionals counsel them. Whether or not the crying is objectively excessive is irrelevant because perception is reality, and if a caregiver is at risk of harming their child something needs to be done to address their concerns. That’s why the best educational campaigns focus on coping skills. One great example is the Period of Purple Crying.

Chiropractic for colic?

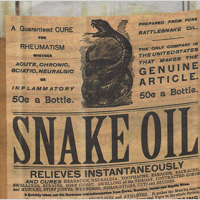

Because this is science-based medicine, we can’t evaluate the potential role of chiropractic in the treatment of colic without devoting some space to the plausibility of such an intervention. Don’t worry, this will be brief. There is none.

The only purported mechanism of action involves fundamentalist chiropractic beliefs regarding subluxations and their potential role in the function of specific organ systems or general health. These beliefs are not based on any legitimate science. Specific chiropractic interventions would be implausible if the excessive crying was objectively present and caused by an underlying medical condition and it would be implausible if colic was, as I believe, a combination of normal development and parental perception. It is possible that a caregiver might perceive chiropractic to “work”, however, because of various non-specific placebo effects, in particular not taking into account the natural course of colic.

So, in my opinion, any claims of effectiveness for chiropractic would need to be based on an extremely robust evidence base in order to counteract the plausibility problem. But when it comes to pediatric research, the chiropractic literature is generally full of anecdotes and case reports. You will, in fact, very frequently find these stories of treatment success on the websites of individual chiropractic practices or even touted by mainstream chiropractic organizations. And while anecdotal observations can serve an important function in medicine by generating hypothesis, revealing potential pitfalls in our management recommendations, or giving insight into our patient’s lived experiences, they are not particularly helpful when it comes to determining if an intervention is safe and effective.

In today’s post, however, I get to discuss a bit of chiropractic research that isn’t simply a collection of anecdotes. It’s an actual study…with blinding! Recently published in Chiropractic and Manual Therapies, the official journal of the Chiropractic and Osteopathic College of Australia (no website available), this study investigated the potential effect of chiropractic care on infant colic and was designed as a single-blind randomized controlled trial conducted at four Danish chiropractic clinics.

After a not terrible discussion of colic and a nod to the lack of quality research on chiropractic for colic, the authors describe subject recruitment:

Children were recruited at the age of 2 to 14 weeks with symptoms of infantile colic defined as episodes of excessive crying and fussing that lasted at least 3 h a day, for at least 3 days a week in the previous 2 weeks. The children were otherwise healthy and thriving with appropriate weight gain. The children were ineligible if they had received chiropractic treatment before. Concomitant treatment for colic (e.g. reflexology) was not permitted during the project period.

Caregivers learned of the study from the media, maternal and child health nurses, and the participating chiropractic clinics. If interested, they then contacted the primary investigator themselves. After a phone interview screening, a home visit was arranged if appropriate and the potential subject was evaluated for any potential medical concerns and baseline information on the baby’s crying was obtained. So right off the bat there is a potential for selection bias where these caregivers might already be convinced that chiropractic is an effective treatment modality for infants. Blinding would need to be really well done.

Caregivers were also instructed on how to keep a detailed diary of their infant’s behavior:

These were filled out with a variety of symbols representing different aspects of the child’s behavior, including the amount of inconsolable crying (crying without an obvious reason that could not be comforted by the parents), the time the child needed to be held and rocked to limit crying (crying without any obvious reason that was only partly and briefly limited if the child was constantly held and rocked), the time the child was awake and content, the time spent sleeping, feeding patterns and bowel movements. Consolable crying with an obvious reason where the child was easily comforted e.g. hunger, or a soiled diaper was recorded as ‘awake and content’. To limit recall bias and make the recording of information as precise as possible, the parents were advised to fill in the diary several times a day, e.g. every time the baby was fed.

It’s good that they were attempting to make this as objective as possible, but including numerous secondary outcomes unrelated to crying (spitting up, burping, stooling patterns, etc.) comes across like a fishing expedition in order to have some random noise to pad their conclusion with. But maybe I’m just being cynical.

Parents obtained 3 days’ worth of baseline data and then met with the primary investigator at a chiropractic clinic in order to iron out any problems:

Here, any difficulties filling out the diary were identified, and the parent’s assessment of the crying pattern was evaluated in a second interview-based questionnaire

This is another point where so-called researcher degrees of freedom, whether manipulated intentionally or not, could lead to a false positive result. I don’t like that the primary investigator had so much face time with caregivers when the outcomes being measured are this subjective. Again, perhaps I’m being overly cynical, but it would be easy to unintentionally coach them to be assess their infants as fussier at baseline than they might have otherwise, which could make an intervention for colic seem more helpful than it really is. It is an unfortunate reality that we have to be aware of these potential issues.

Subjects were then randomized to either the treatment or control groups. Caregivers were blinded to the allocation but not the treating chiropractor. Fortunately, the research team and statistician were also blinded until after analysis was completed. It’s entirely possible that the blinding of the caregiver broke down at the individual practice clinics, but only 60% correctly guessed which group their child was in. As would be expected, caregivers were more likely to guess that their child was in the treatment group when their child’s crying seemed to improve more substantially.

In the end, 185 infants were included in the study and randomized into either the control or treatment group and were seen at a participating clinic twice a week for two weeks. Those in the control group would simply be entertained for 5 minutes behind a closed door and then returned to their caregiver. Infants in the treatment group underwent the standard infant chiropractic nonsense:

For children in the intervention group a full examination, including movement palpation of the joints was carried out, and the manual therapy applied was individualized according to any biomechanical dysfunction found. Thus, the chiropractors were informed that manual therapy could include manipulation or mobilization of the spine and/or the extremities as they found indicated by the child’s potential biomechanical dysfunctions, including movement restriction, tenderness or an obvious asymmetry in the muscles or joints. The treatment technique for restricted joint movements in this age group is, in general, very light short-term pressure with fingertips and gentle massage in case of hypertonic muscles.

Naturally there were problems unique to chiropractic “discovered” in every single subject in the treatment group. In the history of baby chiropractic, a patient being evaluated for the first time has never been told that they don’t have a problem that can only be fixed by some kind of adjustment or manipulation. But no evidence exists to support these biomechanical dysfunctions, movement restrictions, or asymmetries in infants.

After the 4th visit, caregivers continued keeping a daily behavior diary for a few more days and then received a coupon for 4 free chiropractic treatments. So yes, this whole thing was just marketing for the participating clinics. There I go again.

So did it work?

No. It didn’t. The primary outcome measured was the change in daily hours of inconsolable crying requiring soothing techniques such as holding and rocking. There was a small difference when looking at the percent of each group that had a reduction in crying by at least one hour, with 63% of babies in the treatment group compared to 47% in the control group. But when controlling for potential confounding variables such as age and baseline hours of crying, they did not find a statistical difference between the treatment and control groups when looking at mean reduction in hours of crying. There were also no meaningful differences between the groups for any of the secondary outcomes either, most importantly the caregiver’s assessment of the severity of their child’s colic.

The study authors did some light spinning of the results:

The results of this randomized, controlled trial suggested an overall small positive effect of chiropractic care on infantile colic, but the clinical significance is debatable. We found a reduction in crying time of half an hour in favor of the treatment group, which was not statistically significant. However, a larger proportion of participants in the treatment group achieved a predefined clinically relevant reduction in crying time of 1 h at a statistically significant level; in short, more children improved in the treatment group, but the difference was small.

Honestly, that could have been worse. They admit that there is a difference between statistical and clinical significance. They don’t admit, however, that it is likely that the small difference found wasn’t even real and would likely disappear in a larger study. And then this happened:

From a clinical perspective, the mean difference between the groups was small, but there were large individual differences, which emphasizes the need to investigate if subgroups of children, e.g. those with musculoskeletal problems, benefit more than others from chiropractic care.

The authors apparently fully planned to use the same data in an attempt to find a more substantial benefit through secondary statistical analysis/data massaging as a plan B:

We proposed this when planning the study, and investigations into potential treatment modifying factors will be the next step in the analyses of the study and will be reported in a separate article.

Here is the separate article, which found no treatment modifying factors of any use. It really is a mess of a study that involved several made up indicators of “musculoskeletal problems” such as “Does the child resist dressing” and “Is the child tense during meals?” They concluded that “None of the preselected items or predefined indices were valuable for identification of infants with potentially larger gain from manual therapy than others”. This did not stop them from calling for research into some other random findings suggested by the data. It really never will end, will it?

And don’t think I didn’t notice that the chiropractors providing treatment in the initial study diagnosed every subject in the treatment group with musculoskeletal problems. So it makes absolutely no sense whatsoever that they then act like this wasn’t the case in the second study’s reanalysis of the initial data. It really is all just a house of cards.

Conclusion: Chiropractic is not an effective treatment for unexplained infant crying

I applaud the effort by these researchers to design a study involving some degree of blinding and control, rather than just putting out a call for anecdotes. But these two studies are negative and do not change my assessment of the plausibility of chiropractic as a treatment for unexplained infant crying, or if you must give it a name, colic. Caregivers would be better served talking to a qualified medical professional about ways to cope with crying until it naturally decreases over time.