A memory

One of my most vivid memories from medical school is holding the hand of an older Black woman in LA County Hospital as she screamed in pain while an OB resident performed a procedure on her genitalia without adequate anesthetic. The resident seemed mostly annoyed by the patient’s wails and her inability to sit still. I still feel awful for not speaking up about it. I think one reason for my silence was that I was ignorant of an important truth – doctors are not immune to bias.

“There is no credible evidence that physicians are biased, or healthcare is systemically racist”

With this in mind, let’s examine some thoughts by Dr. Stanley Goldfarb, a former associate dean of curriculum at the University of Pennsylvania. I was reminded of Dr. Goldfarb when I encountered a podcast he made titled “Taking CRT Out of the Exam Room“.

Dr. Goldfarb caused a stir in 2019 with his article “Take Two Aspirin and Call Me by My Pronouns” in which he defended the idea that “the stated purpose of medical education since Hippocrates has been to develop individuals who know how to cure patients”. He said the traditional medical school model has “produced a technically proficient and responsible physician corps for the U.S.” He said that instead of teaching students what they need to know to heal sick people, medical schools now “focus on eliminating health disparities and ensuring that the next generation of physicians is well-equipped to deal with cultural diversity.” While he felt this was a laudable goal, he claimed that “teaching these issues is coming at the expense of rigorous training in medical science.”

Dr. Goldfarb does not deny health inequity exists. He’s said:

We have groups of patients whose health is much worse than other groups of patients … And so I think this represents a crisis. And the response … is just the wrong

However, Dr. Goldfarb does not feel the medical system is to blame, saying “Health disparities do exist among racial groups, but physician bias isn’t the cause”. Like a good doctor, he feels we must first diagnosis the problem before we can properly treat it:

No, the reason we have a crisis is because of personal behaviors, understanding of the risks of illnesses, and access to the health care system. This is the nature of the crisis … It will only get worse if we put all our resources into the wrong solution to the medical problem.

He worries that, “As race-based ideology dominates ever more of medical research and education, nonscientific factors will increasingly determine what treatments patients receive”, and that if patients are encouraged to “seek out physicians matching their own race… we could be on the path to medical apartheid”.

Dr. Goldfarb has started an organization to oppose what it perceives to be Critical Race Theory in medical education. It believes that “There is no credible evidence that physicians are biased, or healthcare is systemically racist” and that:

Critical Race Theory is ultimately making health more biased and discriminatory, not less.

Though Dr. Goldfarb’s provides no evidence to support this bold claim, he believes he is doing crucial work:

As a long-time medical educator and practitioner, I will not be deterred by slanders and acts of intimidation. I will continue to ask uncomfortable questions in pursuit of the truth and improved outcomes for patients, not least because I’ve heard from countless other medical professionals who are deeply concerned yet afraid to speak out.

Areas of agreement

Let me start by saying that I agree with Dr. Goldfarb on multiple essential points.

First, I agree that “We have groups of patients whose health is much worse than other groups of patients” and that “this represents a crisis”. There are plenty of examples where different groups have starkly different health outcomes. It’s tragic that people in nearby zip codes can have greatly different life expectancies. The explanations for these disparities are collectively known as the social determinants of health, and they clearly have a profound impact. Some of Dr. Goldfarb’s critics accuse him of denying these disparities even exist, which is not a fair characterization of his position.

Second, he’s right that the medical community can’t be blamed for all these disparities and that personal behaviors matter. Are doctors the only reason many White evangelicals refused the COVID vaccine or why menthol cigarettes are popular amongst Black Americans? I don’t think so. To argue otherwise would be to infantilize our patients and vastly overstate our own power.

Third, I agree the essential purpose of medical school is to train “individuals who know how to cure patients”. Only a few students will become public health commissioners. Like me, most will work in ERs, hospital wards, ORs, clinics, and ICUs. Medical students need how to learn to save lives and minimize suffering for the patients they will encounter there. I further agree that to do this well, students need “rigorous training in medical science”. I view that as my mission as an educator, and so I’ve devoted enormous effort to teaching students neuroanatomy, neuroradiology, and the diagnosis and treatment of neurological diseases. The core function of medical school should be to teach students what they need to know to treat patients.

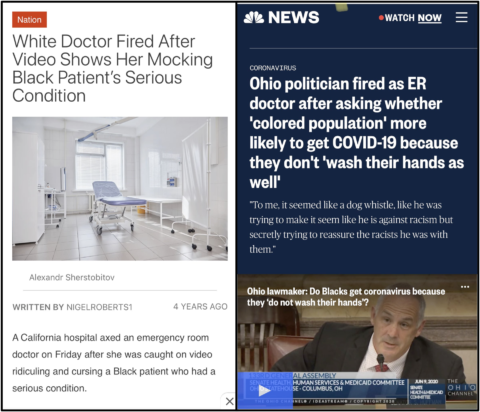

Fourth, I agree that our medical schools have generally been able to “develop individuals who know how to cure patients”. Everyday, in clinics and hospitals all over this country, diverse healthcare workers provide excellent care to diverse patients, and there’s evidence doctors do a solid job of taking care of patients of different races (here and here). There are a lot of good doctors out there. The news isn’t all bad. And when doctors are overtly racist, they can be fired and exposed in the news, at least if their actions are captured on camera. Medicine should have no tolerance for such people, and I think Dr. Goldfarb would agree with me about this.

Fifth, like Dr. Goldfarb I don’t want patients to feel they must “seek out physicians matching their own race” to get proper treatment. Though I understand why some patients may choose to do so today, we should strive for a world where everyone receive excellent, compassionate care from whomever they see. My hospital has a psychiatric ward for patients who speak Mandarin or Cantonese. This makes perfect sense. Beyond this, I don’t want hospitals to be segregated. I don’t know anyone who wants this.

Sixth, I agree that criticisms of “these issues” are not off-limits. Dr. Goldfarb’s often excoriates the Implicit Association Test and its purported ability to reveal bias, for example. This is entirely fair, and like any subject in medicine, scholarship on “these issues” needs to be held to high standards. Studies that purport to show racial bias in medicine are not sacrosanct, and those who reveal their methodological flaws are not racist. They are doing important work (here and here).

Finally, though Dr. Goldfarb may think he’s the only one to realize this, those who work in this space know the potential pitfalls of diversity education. For example, it’s no secret that:

Teaching “typical” characteristics of minority groups frequently promote stigmatization without promoting healthcare outcome improvements.

And though we may disagree on how to best get there, we all agree that “promoting healthcare outcome improvements” is the only thing the matters.

Areas of disagreement: These issues are rigorous medical science and doctors are not free of bias

Despite this, I disagree with Dr. Goldfarb’s central thesis. He claims that “teaching these issues is coming at the expense of rigorous training in medical science.” But “these issues” are rigorous medicine. Serious researchers have put a lot of work into this field and they’ve made important findings. However, Dr. Goldfarb implies that unless doctors are exonerated, investigations into the causes of racial disparities are not rigorous medical science. Of course, any study that begins with a predetermined conclusion is not rigorous medical science.

Moreover, contrary to what Dr. Goldfarb claims, there is evidence that doctors are not the only humans on the planet who are free of bias. Would that Black woman at LA County Hospital have received better pain control had she been a wealthy White celebrity in Beverly Hills? Of course. There’s no way she would have been left screaming that way. Though Dr. Goldfarb writes that “There’s no credible evidence that physicians are racist”, I’ve not seen him explain why Black patients receive less pain treatment than White patients. Instead, Dr. Goldfarb simply denies that this happens at all.

However, there is a vast literature on this and many similar topics. There are very few significant health metrics where the numbers are worse for White people than for any other race. Native Americans commit suicide at a higher rate, and Black overdose deaths exceeded White overdose deaths last year for the first time in 20 years, in part because White people received better treatment. Even Black children receive less pain control than White children. Things would be much better if all Americans received the same healthcare as most White Americans. Though the medical system is not solely responsible for these disparities, it is not the only American institution that is utterly without blemish today.

The evidence for this is literally everywhere. It turns out that a lot of medical students have some pretty strange beliefs, undermining Dr. Goldfarb’s claim that doctors are somehow immune to the same biases as everyone else. According to research by Dr. Janice A. Sabin racially biased beliefs do make their way into medicine:

“Black people’s nerve endings are less sensitive than white people’s.” “Black people’s skin is thicker than white people’s.” “Black people’s blood coagulates more quickly than white people’s.” These disturbing beliefs are not long-forgotten 19th-century relics. They are notions harbored by far too many medical students and residents as recently as 2016.

In fact, half of trainees surveyed held one or more such false beliefs, according to a study published in the Proceedings of the National Academies of Science. I find it shocking that 40% of first- and second-year medical students endorsed the belief that “black people’s skin is thicker than white people’s”.

What’s more, false ideas about black peoples’ experience of pain can lead to worrisome treatment disparities. In the 2016 study, for example, trainees who believed that black people are not as sensitive to pain as white people were less likely to treat black people’s pain appropriately.

This seems problematic. Maybe it would be good to identify these racist myths and disabuse students of them. To me, this seems to be an essential part of developing “individuals who know how to cure patients”.

Areas of disagreement: Learning about bias in medicine is not a personal attack on doctors

A central concern of Dr. Goldfarb is that learning about bias in medicine will hurt doctors’ feelings. He wrote:

Having talked with many physicians, I know that unwarranted accusations of racism are contributing to physician burnout and early retirement, making it harder for patients to receive care, especially in vulnerable communities.

A dishonest student once falsely accused me of not giving her time off to attend a relative’s funeral. So while some doctors may have faced unwarranted accusations of racism, I’m unaware of any evidence this is causing a mass exodus from our profession. I’ve not met anyone who is considering leaving medicine for this reason. Still, I doubt Dr. Goldfarb is not inventing such doctors out of whole cloth. The rules have changed, old jokes aren’t funny anymore, and no one likes to be accused of racism. However, too many doctors view any discussion of racism as a personal attack. This reveals more about the sensitivities of these doctors than anything else, and their delicate sensibilities are not a valid reason to ignore uncomfortable truths. Moreover, for every doctor who’s retired due to unwarranted accusations of racism, there are certainly others who’ve curtailed their ambitions or left the field because they experienced racism.

Of course, the purpose of discussing “these issues” shouldn’t be to make students feel guilty. Racial myths are part of our culture milieu, and a student who believes such a myth isn’t the moral equivalent of a KKK Imperial Wizard. Rather medical schools should need to teach about these myths to make sure no student graduates believing them. Additionally, there are doctors who’ve gotten away with horrible behavior simply because their actions weren’t filmed. Students should know these doctors are out there. Students should know they don’t want to make the news this way.

Dr. Goldfarb doesn’t see it this way. He said that anti-bias education “undermines the whole idea of a trusting physician-patient relationship”.

He doesn’t realize that “nonscientific factors” already determine what treatments many patients receive, and that this contributes to a lack of trust in our profession. He doesn’t grasp that patients might not feel the need to “seek out physicians matching their own race” if they knew that all doctors were cognizant of “these issues”. The idea that patients may perceive doctors’ behavior as racist even when he does not, does not seem to occur or matter to Dr. Goldfarb. He seems to feel patients and doctors alike should adopt his standard for what is and is not racist, and he sees no rational reason why a Black woman may prefer a Black obstetrician.

The reason, of course, is very simple – these women feel they will get better care with these doctors. It’s the exact same reason everyone chooses their doctor. Doctors should be dismayed that some patients have lost trust in some members of our profession. We can either pretend our patients have all been brainwashed by CRT or we can strive to earn their trust back. The choice shouldn’t be controversial. We should want all our patients to feel comfortable under our care. It may take some getting used to, but it’s less effort to try to call someone by their preferred pronouns than to write a book about why doing so is destroying American medicine. If it makes my patient feel more comfortable, I’ll do it. The only cost to me is a tacit admission that I value my patient’s self-identity.

Areas of disagreement: It’s OK to learn about problems we can’t solve, though learning about these issues is related to patient care

Another reason Dr. Goldfarb feels medical schools should not spend time on “these issues” is that doctors are often powerless to solve them. He wrote:

Above all, the medical profession should abandon the fantasy that physicians can be trained to solve the problems of poverty, food insecurity and racism. They have no clinical tools with which to address these issues.

He’s not entirely wrong. I’ve never handed an apartment key to a homeless person nor solved a patient’s food insecurity for longer than their hospital admission. There’s often very little we can do for people who have nothing. Moreover, not only do I not have the cure for racism, I will fail to convince many people that it can be a problem in medicine. Unfortunately, “these issues” do not have simple solutions or they would have been solved already. Dr. Goldfarb feels all doctors end up doing with “these issues” is referring the patient to a social worker, so there’s no reason for students to learn about them. They are literally someone else’s problem.

However, students spend a ton of time learning about problems they cannot solve. Does Dr. Goldfarb feel it’s useless for students to learn that the gene for Huntington’s disease is a CAG repeat on chromosome 4? Of course not. Have I helped a single patient by knowing that? Of course not. Like every doctor, my brain is filled with facts that are crucial to understanding the human body and disease, but have zero practical impact when actually treating patients. Instead of saying that students need not learn any such information, we should agree that it’s important for them to learn about all the factors that promote health and all the factors that are a detriment to it, even though we can’t fix everything.

Dr. Goldfarb believes that it’s inappropriate for any doctor to use a tool that isn’t a “clinical tool”, presumably a medication, procedure, or recommendation to exercise. Dr. Goldfarb gives no reason why doctors should so restrict themselves to these uses of “clinical tools”. Or perhaps we should drastically expand our concept of “clinical tools”.

Because while doctors can’t fix everything, we can occasionally fix some things, and this can make a big difference to some of our patients. Of course, “these issues” are not someone else’s problem. Anything that drastically affects the health of our patients is our problem whether we want it to be or not. We should use every tool at our disposal to help our patients. I discussed this previously in my essay on malingering when I wrote:

A referral to a domestic violence shelter or a suggestion that corrections officers transfer an endangered inmate to a safer jail unit can be life-altering. I wish I had been more attuned to this early in my career.

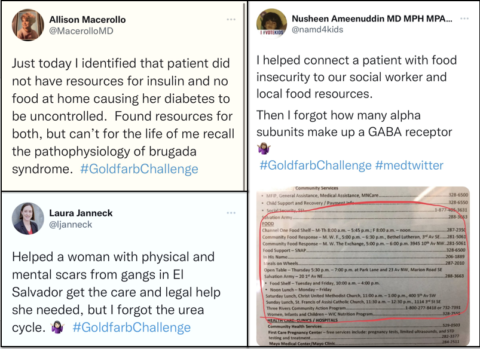

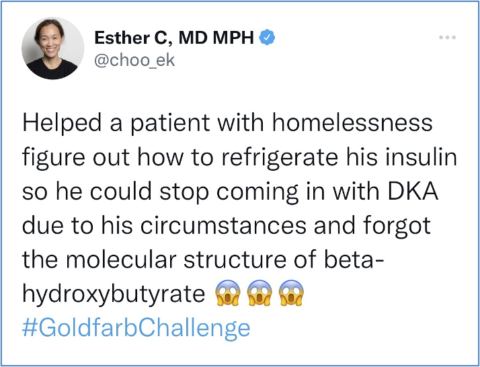

I learned all of this and more through my experience working at a large public hospital for nearly 20 years, and I’m not the only one who’s figured this sort of stuff out. Dozens of doctors Tweeted what they’ve learned under the hashtag #Goldfarbchallenge. You should definitely click on that link. You’ll why I said there are a lot of good doctors out there.

While much of the practical side of “these issues” must be learned through experience, learning about their importance should begin early in medical school. Virtually none of it was discussed in my training, which is too bad. I should have been encouraged to think about “these issues” from the start of my career, instead of having them treated like an afterthought. Again, there’s often very little we can do for patients, but I wonder what opportunities I’ve missed to help them over the years because I felt their social problems were not my problem. I wonder if Dr. Goldfarb is similarly curious about what opportunities he may have missed to help his patients.

Moreover, while medical school should focus on teaching students how to treat individual patients, it’s not wrong to get them thinking about the bigger picture. Yes, the fundamental goal of medical school is to train doctors who can treat women with obstetrical emergencies. But students should also be encouraged to think about why these tragedies are more common in Black women and what can be done to prevent them in the first place. I’m not saying every doctor must embrace only progressive policies as the only solution to societal problems (I don’t), nor must every doctor be an activist in their spare time. Tired doctors can do whatever they want when they get home from work. But it’s a good thing when someone is passionate about trying to fix problems in their community.

This sort of work should be appreciated and encouraged in our profession, because sometimes doctors’ actions matter. Circling back to menthol cigarettes, doctors spoke out against them, and the FDA is now considering a ban. While not every doctor must agree with this action, it shows that doctors are not destined to be powerless spectators regarding the factors that influence our patients’ health. And with recent news, our voices are needed now more than ever.

Additionally, it’s within the purview of medicine to formally study what interventions do and do not work for our most vulnerable patients. A recent study of intense medical and social outreach (healthcare hotspotting) to patients with “medically and socially complex conditions” failed to show any benefits, unfortunately. Dr. Goldfarb should appreciate that studying these interventions is as every bit “rigorous medicine” as studying a new medication. Hopefully an enterprising student will be motivated to come up with something that works.

Areas of disagreement: Learning about these issues won’t leave medical students unprepared to be doctors

Another of Dr. Goldfarb’s core worries is that learning about “these issues” will take an inordinate amount of time, preventing students from learning the enormous amount of material he feels they really need to know, such embryological development of the thyroglossal duct. He knows that time is a fixed commodity and believes that “Medical schools increasingly are preparing physicians for social activism at the expense of medical science”.

Like Dr. Goldfarb, I believe students should learn the basics, even if much of it is a rite of passage to be honest. But I’ve not seen him present evidence that learning about “these issues” is causing worse outcomes in patients as unprepared students transition into doctors. If he were right, we should have noticed deficiencies in young doctors by now. As I will explain, I think they’re better prepared than I was. They’ll know they’ll be graded on both their ability to identify the anconeus on a cadaver and whether or not they’re the type person who cares if their patient is in extreme pain.

Of course, students are smart enough to learn multiple things at once, and studying “these issues” need not take that much time. I imagine a couple lectures per month on “these issues”, as is done at my medical school, could convey an incredible amount of valuable information without leaving students deficient in the traditional curriculum.

Alternatively, “these issues” can be woven in lectures when appropriate. Many lectures make reference to heroic figures in medical history. That’s great, but it’s not wrong for a speaker to spend one minute informing students about people like J. Marion Sims, the “Father of Gynecology” who “conducted painful experimental surgeries on enslaved black women without using anesthesia”, though he used it with his White patients. “Lucy’s agony was extreme,” he wrote about one of these enslaved women. “She was much prostrated, and I thought that she was going to die”. A statue honoring this torturer was removed from NYC only four years ago. Though this dark history need not be discussed in every lecture, it shouldn’t be swept under the rug either. It may clue us into the fact that some of what we like to think of as ancient history is actually our present day reality.

“We in academic medicine have a duty to bring to light racist misinformation, stereotypes, and unconscious attitudes that contribute to disparities in patient care today.”

I may be projecting here, but I sense that on one level Dr. Goldfarb just doesn’t want to think about “these issues”, or he doesn’t want them to be true. So anytime anyone brings them up, they are dismissed as being “woke” or “promoting CRT” or some such buzzword that immediately signifies to his audience “don’t give this any serious thought“.

I can empathize with Dr. Goldfarb about this. I want to believe the best about my profession. Hearing unpleasant truths can make me feel uncomfortable and defensive. I certainly don’t want to believe I’ve ever undertreated a Black patient’s pain or mistreated anyone I work with. It’s nice to imagine that a Black inmate will receive the same care as a White titan of industry. But we know that’s not the case, and reality can’t be wished away by evidence-free moral panics that the future of American medicine is being sacrificed on the altar of wokeism.

While Dr. Goldfarb is pessimistic about the future capabilities of today’s students, I am not. Most students I meet understand that “these issues” are every bit as important to patient care as being able to identify Bowman’s capsule on a histology slide. They realize “these issues” are part of their curriculum for one reason only – to make them better doctors. They understand that a Black patient with a broken arm might fare better with a doctor who knows that Black patients feel pain just like White patients, than by a doctor who knows only that osteoclasts have multiple nuclei and a “foamy” cytosol. I believe these future doctors will have a greater understanding of the issues their patients face compared to when I was their age, and they’ve been able to teach me some important things. One even authored a book to help doctors identify clinical signs on darker skin. Though this is the only topic in medicine where skin color really matters, nothing like it existed until recently, in a profession Dr. Goldfarb believes to be free of racism.

Most students would agree with the conclusion of Dr. Sabin’s article:

As a nation, we must continue to reckon with the lingering history of racism in medicine. We in academic medicine have a duty to bring to light racist misinformation, stereotypes, and unconscious attitudes that contribute to disparities in patient care today. Dramatically reducing, and perhaps even eliminating, racial and ethnic disparities in pain treatment is an attainable goal — and a moral imperative.

Perhaps the OB resident I encountered in medical school would have cared about her patient’s screams had she recognized this. Maybe I would have spoken out if I had.