Combination drugs, or fixed dose combinations (FDCs), combine two or more active ingredients in a single dosage form. One company added LSD to their birth control pills so you could take a trip without the kids. OK, that’s just a joke, but the FDA has approved a new FDC, Consensi, that is almost as laughable.

There are good reasons to combine drugs. HIV/AIDS patients used to have to take a complicated regimen of pills, some as often as five times a day. Now all they need is a single once-daily pill that combines two to four anti-retroviral drugs. Oral contraceptives combine two hormones, estrogen and progestin. There are numerous FDC blood pressure pills; for instance, a beta blocker may be combined with a diuretic. The Parkinson’s drug carbidopa/levodopa combines those two ingredients to increase the availability of levodopa to the brain and to reduce side effects. The two antibiotics trimethoprim and sulfamethoxazole are combined in products like Bactrim and Septra because they act together synergistically against bacteria. The four anti-tuberculosis drugs isoniazid + rifampin + ethambutol + pyrazinamide are combined in a single pill.

There are good reasons for combining these drugs. Combinations simplify treatment, improve patient compliance, reduce prescribing errors and inadequate regimens, and may reduce drug supply management problems and cost. Studies have shown that these combinations are safe and effective, and there is plenty of evidence that FDCs improve compliance. Patients appreciate the convenience and the reduced co-pays (for one pill instead of two). But not all combinations make sense.

Sometimes drugs are combined for reasons other than therapeutic benefit. Drug companies create FDCs as a way to extend their proprietary rights, increase prices, and improve marketability. It is much less costly for them to combine existing drugs than to develop new ones. The FDA does not usually require additional studies before approving a combination product as long as there are good data on the components and no concerns about safety issues.

For the period 1990 through 2013, the FDA approved a total of 131 prescription FDC products. 13 have been discontinued because of poor commercial performance or the development of a better product. 117 had two active components, 12 had 3, and 2 combined 4 components. A polypill with 5 components (3 anti-hypertensive drugs plus a statin and aspirin) showed promise on initial testing, but never took off.

The big question is whether a combination offers advantages that outweigh the disadvantages. There is no way to adjust the amount of one component. The FDC may contain more or less of one component than is ideal for an individual patient. If adverse reactions occur, it’s hard to know which component is responsible. Patients may be over-treated when they might have responded to a single component.

There are lots of rational combination drugs with advantages that outweigh the disadvantages. But there are also irrational combinations that beggar the imagination.

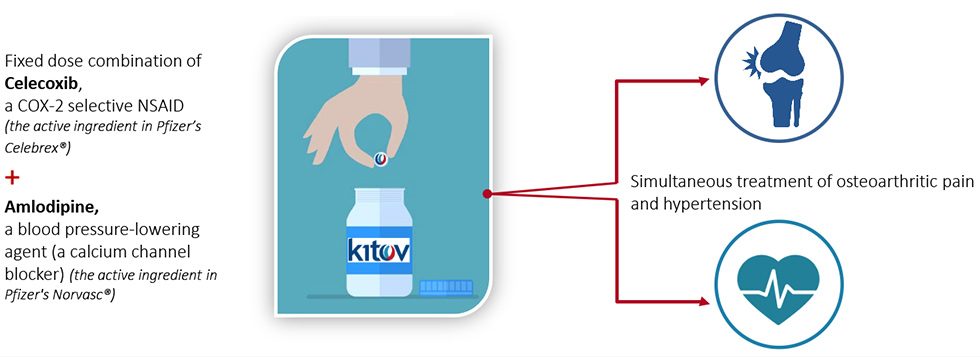

The FDA recently approved Consensi, a combination of treatments for two very different diseases. It contains amlodipine, a common drug used to treat high blood pressure, and celecoxib, a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID), used to relieve the pain of osteoarthritis. It comes in 3 strengths with varying doses of amlodipine, but all formulations contain the same amount of celecoxib: 200 mg. The company website says “ConsensiTM is under patent protection in the U.S. until 2030 and will be the only NSAID whose labeling indicates a reduction of blood pressure and consequent risk reduction of heart attack, stroke and death.”

The Medical Letter recently reviewed Consensi. Their conclusion:

There is no good reason to use the fixed-dose combination…The cost of the combination is much higher than the cost of the two components taken separately, and continued daily use of celecoxib can result in serious adverse effects, including renal and cardiovascular toxicity. Elderly patient should minimize their use of any NSAID, including celecoxib.

The cost for 30 days of treatment with Consensi is $1,287. Generic amlodipine alone costs $1.10. Generic celecoxib alone costs $34.40. Consensi is available at Costco with a free coupon for a reduced price of $1,104.13. Consensi carries a boxed warning of the risk of serious cardiovascular and gastrointestinal events.

The Coeptis and Kitov companies have entered into an agreement for commercialization under which Kitov will receive millions of dollars in royalties, milestone, and reimbursement payments.

Conclusion: An irrational product

It doesn’t make sense to combine these two ingredients for such very different diseases. How many patients have both diseases and would benefit from Consensi?

High blood pressure is seldom controlled on a single anti-hypertensive drug. In the best possible scenario, if a patient happens to have high blood pressure that is already well-controlled with amlodipine alone and also happens to have osteoarthritis that is already well-controlled with 200 mg of celecoxib alone, it would be more convenient to take one combination pill than two single pills. But does that convenience justify an added cost of over a thousand dollars a month, over $12,000 a year? I don’t think so! Patients might argue that they don’t have to pay for it, that insurance pays; but if insurance expenses go up, someone has to pay, and it ultimately impacts all of us.

Thumbs down!