By definition, alternative medicine consists of treatments that either have not been shown to work or have been shown not to work. To paraphrase an old adage yet again, medicine that has been shown to work with an acceptable risk-benefit ratio ceases to be “alternative” and becomes simply “medicine”. We also know from multiple sources of data that the use of alternative medicine to treat curable cancers is highly correlated with a decreased chance of surviving such cancers. Indeed, less than a year ago, I discussed in my usual inimitable fashion (and at my usual inimitable length) about a study showing just that, in which alternative medicine use was associated with a 2.5-fold increased risk of death for combined breast, prostate, lung, or colorectal cancer patients, and a whopping 5.7-fold increased risk of death for breast cancer patients. That was a relatively small study, however, and only looked at patients choosing to use alternative medicine instead of conventional cancer treatment. Even so, its findings were striking.

But what about so-called “complementary and alternative medicine” (CAM, also now more commonly referred to as “integrative medicine”)? That’s a bigger question, because most cancer patients who use unscientific treatments (or, as I like to call them, quackery) don’t use them instead of conventional cancer therapies, but rather in addition to such therapies. Indeed, there is a whole specialty known as “integrative oncology” devoted to combining quackery with real science-based oncology. (Yes, I know that I’ve probably just offended the Society for Integrative Oncology by saying that, but it’s true. After all, the SIO welcomes naturopaths as in its membership, and two past presidents have been naturopaths.) Their rationale is that it’s the “best of both worlds,” but is it really? For instance, we know that patients who choose to use CAM, particularly dietary supplements, are more likely to refuse adjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer, with higher CAM use more strongly correlated with refusal of chemotherapy. And these are results that were published by a naturopath associated with SIO!

Of course, the counterargument made by CAM advocates, like SIO, is that “integrative oncology” makes it more likely that cancer patients will complete their science-based recommended chemotherapy, because they can receive whatever “natural” therapies they’re interested in in addition to the chemotherapy and are thus less likely to decide to forego chemotherapy in favor of quackery. We don’t know whether that is true or not, but a recent study suggests that the argument of the SIO and other advocates of “integrative oncology” might not be as potent as they think it is. The study was published in JAMA Oncology last Thursday and is entitled “Complementary Medicine, Refusal of Conventional Cancer Therapy, and Survival Among Patients With Curable Cancers.” It’s by Skyler B. Johnson, Henry S. Park, Cary P. Gross, and James B. Yu, basically the same team that did the study last year on alternative medicine and decreased cancer survival. Its findings are worth discussing in depth.

Complementary medicine: Who chooses it?

I think it’s worth repeating something I discussed last year regarding one aspect of cancer that’s very important, at least with respect to alternative medicine or “CAM”. Unlike the case for many conditions commonly treated with alternative medicine, whether or not a treatment works against cancer is determined by its impact on the hardest of “hard” endpoints: Survival. A patient either survives cancer (however that’s defined, be it five, ten, or whatever year survival) or does not. Even the “softer” endpoints used to assess the effectiveness of cancer treatments tend to be “harder” than for most other diseases, such as progression-free survival (the cancer either progresses after treatment or it does not) or recurrence-free survival (a cancer either recurs after treatment eliminates it, or it doesn’t). Although there are lots of other aspects of cancer treatment to be assessed, such as quality of life and adverse reactions, at the very heart of evaluating any treatment for a specific cancer are the questions: Does the therapy save the lives of cancer patients? Does it prolong survival, and, if it does, by how much and at what cost? To this, we can add: Does the addition of so-called “complementary” therapies to known, effective conventional cancer therapies improve survival? Does it improve quality of life? For instance, one could argue that if such therapies improve quality of life, they are worth using, even if they have no effect on survival or progression-free survival. However, if such therapies are associated with an adverse effect on cancer survival, the argument that they improve quality of life, even if supported by evidence, rapidly becomes untenable.

So let’s look at the study itself. The authors’ rationale is spelled out in the introduction, with “complementary medicine” henceforth abbreviated, per the authors’ choice as “CM”:

Despite the widespread use of CAM, there is limited research evaluating the association of CM with survival. We previously investigated alternative medicine (therapy used instead of CCT) and showed that its use (vs nonuse) was associated with an increased risk of death,11 but we did not investigate CM. Approximately two-thirds of patients with cancer believe that CM will prolong life and one-third expect it to cure their disease.5 Although it is possible that CM may improve outcomes by helping patients tolerate conventional medical care and complete their recommended therapy, CM may result in inferior survival as a result of delays to receiving proven CCT and refusal of other recommended CCTs.12-14

Therefore, in light of the lack of knowledge regarding the association between CM and overall survival in patients with cancer, we used a large national database to identify patients who underwent CM for cancer in addition to CCT. We investigated factors associated with selection of CM, the association between use of CM and delay of initiation of CCT or refusal of further CCT, and how these factors seemed to mediate survival outcomes in patients who used CM compared with those who used no CM.

The previous study by Johnson et al last year used the National Cancer Database (NCDB), which is a joint project of the American College of Surgeons and the American Cancer Society. It is a clinical oncology database sourced from hospital registry data collected by the more than 1,500 facilities accredited by the American College of Surgeons Commission on Cancer (CoC). Data cover more than 70% of newly diagnosed cancer cases nationwide and are used to develop quality improvement initiatives and set quality standards for cancer care in many hospitals across the US. Not surprisingly, this year’s study uses the NCDB as well. Using this database, the authors carried out a retrospective observational cohort study of 1,901,815 patients from 1,500 CoC–accredited centers across the United States who were diagnosed with nonmetastatic breast, prostate, lung, or colorectal cancer between January 1, 2004, and December 31, 2013. Patients were matched on age, clinical group stage, Charlson-Deyo comorbidity score, insurance type, race/ethnicity, year of diagnosis, and cancer type. Use of CM was defined as “Other-Unproven: Cancer treatments administered by nonmedical personnel” in addition to at least one CCT modality, defined as surgery, radiotherapy, chemotherapy, and/or hormone therapy. Treatment refusal was defined as any NCDB-documented refusal of chemotherapy, radiation therapy, surgery, and/or hormonal therapy found in the patient record. Treatment refusal did not include patients not receiving treatment because of contraindications or patient risk factors, nor did it include cases where treatment was recommended but not received for an unknown reason. Treatment delay was defined as the number of days between diagnosis and first treatment with chemotherapy, radiotherapy, surgery, or hormonal therapy. The results in these patients were compared to a matched cohort of patients pulled from the same database.

Regarding the 258 patients found in the database, the patients who used CM tended to be younger (mean age, 56 vs. 62 years); female (77.1% versus 48.8%); have breast cancer; be of higher socioeconomic status and higher educational level; have private insurance; have stage I and III disease; have a Charlson-Deyo comorbidity score of 1 (i.e., have one relatively mild comorbid condition compared to a score of 0); and to reside in the Intermountain or Pacific West. In other words, these patients were very similar to the patients who chose alternative medicine instead of conventional treatment in the study last year. A prior study also noted the high concentration of CAM schools in these states, and state legislation favoring CAM.

One interesting tidbit that I noticed in eTable 1 in the Supplemental Data section was that, in the multivariate model, those using CM were more likely to be treated in an academic medical center (odds ratio 1.88, p=0.004), which, sadly, is not surprising given how many integrative oncology programs have sprung up like so much kudzu in medical schools and academic medical centers. Sadly, integrative oncology is, if you exclude the Cancer Treatment Centers of America, primarily a creature of academic medical centers—at least thus far. That this is true is primarily a failure as academics like myself to assure that the medicine being taught and practiced in what should be bastions of science-based medicine is, in fact, actually science-based.

The other interesting thing about the characteristics of the patients choosing CM (to me, at least) was that in the raw data (eTable 1 again) they tended to be more common in either stage I or stage III. First, remember that these were potentially curable patients; so patients with stage IV disease at diagnosis were excluded from this study. Stage III patients tend to have the most locally advanced disease and require the most aggressive multimodality therapy to achieve remission or cure; so intuitively it makes sense that such patients might be drawn to CAM or CM. They’re in for a harder time, with larger, more invasive surgeries plus nastier adjuvant treatments. But what about stage I? Well, it turns out that in a multivariate analysis, there wasn’t a significant difference between CM use in stage I versus stage II patients, but there was increased use (hazard ratio 1.68) in stage III patients relative to stage I. As the authors speculate:

We also found an association between a higher stage of cancer and greater likelihood to select CM (vs a lower stage of cancer), which has been unexplored in prior literature, to our knowledge. It is unclear if the higher stage of cancer motivates patients to select CM or if patients who select CM present with more advanced disease as a result of delay in screening or diagnosis, given that the majority of CAM use is intended to prevent illness or disease. There is evidence to suggest that a less hopeful cancer prognosis is associated with use of CM. We excluded patients with incurable disease to account for this potential contributor to use of CM.

As for the rest of the characteristics associated with CAM use (white race, higher socioeconomic status, etc.), these are fairly consistent with the characteristics previously shown in multiple studies to be correlated with CAM use for more than just cancer; so there were no surprises there.

Finally, also remember that this study specifically looked at patients who had chosen at least one conventional treatment for their cancers and also chose CM. Presumably, that means that they chose the first curative modality usually used for these cancers (surgery for breast, colorectal, or non-small cell lung cancer; surgery or radiation therapy for prostate cancer; surgery or chemoradiation for small cell lung cancer). It was thus (mostly) refusal of adjuvant chemotherapy and/or radiation therapy that was correlated with CM use. Adjuvant therapies, of course, are not primarily curative in themselves; they are intended to decrease the risk of disease recurrence.

CAM use and cancer survival

We know that delays in treatment are associated with poorer survival; so the first correlation that the authors looked at was whether use of CM correlated with delays in treatment. Patients who chose CM did not have a detectable delay in initiation of treatment compared to patients who did not use CM in addition to their conventional therapy (29 days versus 28 days between diagnosis and initiation of therapy). CAM/CM use was, however, associated with a higher likelihood of refusing conventional therapy compared to no CAM/CM use, such as surgery (7.0% versus 0.1%); chemotherapy (34.1% versus 3.2%); radiation therapy (53.1% versus 2.3%); and hormonal therapy (33.7% versus 2.8%). These are huge differences in uptake of therapies designed to cure (or increase the probability of curing) these cancers. At the very least, these figures suggest that when the SIO or other CAM advocates claim that CAM is good because it keeps these patients undergoing conventional therapy, they’re either full of it or at the very least way, way, way overstating the case. I suppose one could make the case that the refusal of conventional treatments would be much higher in these patients without “integrative oncology” teams keeping them in the fold, but that’s an argument without any data to support it and this bit of data to suggest that, even if integrative oncology does keep patients wanting “natural” therapies in the fold of science-based medicine, it’s not doing a very good job of it.

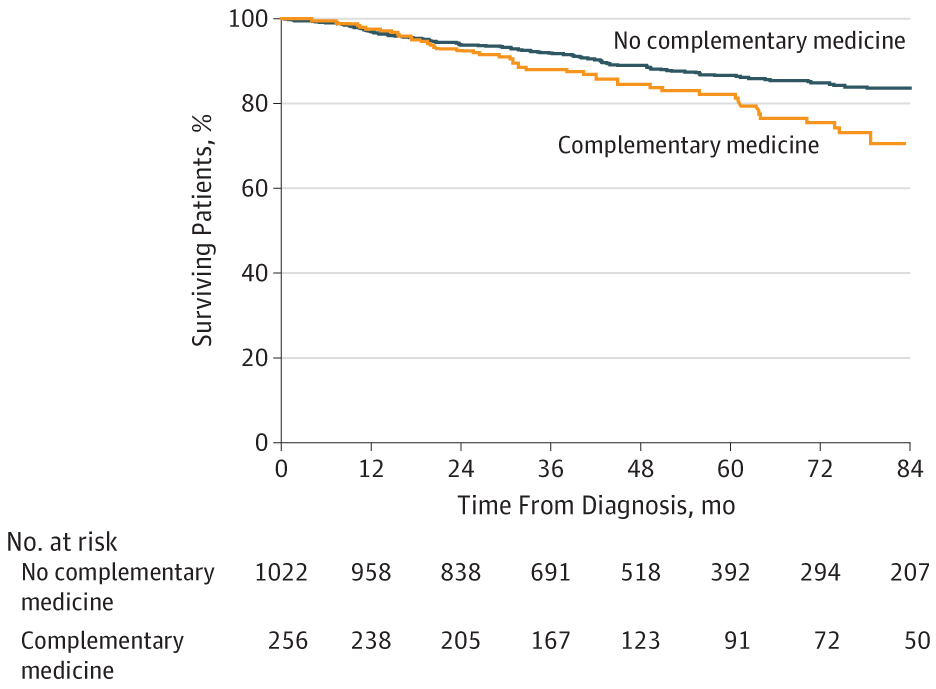

But what about survival, which is where the rubber hits the road in any cancer treatment regimen? In multivariate analysis controlling for cancer type, age, sex, income, educational level, clinical stage, and Charlson-Deyo comorbidity score, use of CM was associated with a greater risk of death (hazard ratio 2.08, 95% confidence interval 1.50-2.90). This Kaplan-Meier survival curve tells the tale:

That was for all four cancers. When the authors looked at specific cancer types, they noted that the use of CM was associated with poorer five-year survival for breast cancer (84.8% vs 90.4%) and colorectal cancer (81.8% vs 84.4%). However, they did not note any statistically significant differences seen in 5-year survival for patients with prostate or lung cancer. In multivariate analysis that did not include treatment refusal or delay, receipt of CM was independently associated with greater risk of death for breast cancer (HR, 1.94; 95% CI, 1.24-3.05) and colorectal cancer (HR, 2.61; 95% CI, 1.21-5.60). Of course, the question here is whether treatment delay or refusal associated with CM use could explain the increased risk of death in patients using CM. The answer appears to be that it explains a fair amount of it. In a multivariate analysis that included treatment refusal or delay, the effect disappeared, and there was no longer a statistically significant association between CM use and the risk of death (HR, 1.39; 95% CI, 0.83-2.33). Thus, the negative correlation between CM use and cancer survival appears to be due primarily, if not completely, to the association between CM use and treatment refusal, a conclusion noted in the Discussion section.

Finally, this study, of course, is not without its shortcomings. First of all, it is retrospective and observational, which means that one can always question how well confounding factors were controlled for by the authors. Another significant limitation is that this study could not incorporate into its multivariate model confounders that could influence survival, such as “aversion to cancer screening, refusal of treatment of noncancer-related comorbidities, body mass index, smoking history, burden of disease, functional status, individual income and educational levels, details about incomplete or dose-reduced treatments, and cancer-specific survival.” (I’m not sure about BMI, as the NCDB does record height and weight, from which BMI can be calculated.) On the other hand, it’s quite possible that the adverse association between CM use and cancer survival might have been underestimated because patients receiving CM were younger, more affluent, privately insured, and, by and large, healthier than those who didn’t use CM, which could have produced a bias towards greater survival for patients who used CM. Also, there’s no evidence about types of CM used.

From my perspective, though, this is probably the biggest problem with the study:

The use of CM was likely underascertained given patients’ hesitancy to report its use to clinicians and for database registrars to code this use reliably. However, this factor was likely a highly specific variable, which includes only those who actually used 1 or more forms of CM. In addition, it is possible that clinicians were more likely to document the use of CM when patients were using noteworthy therapies that may have resulted in refusal of CCT.

Given that only 0.01% of the patients examined fit the inclusion criteria of using CM plus at least one conventional therapy tells me that CM use was probably seriously under-ascertained. How representative this subset of patients is of the likely much larger number using CM during that period can be debated. This, however, is a shortcoming of the NCDB, which was not designed to study alternative medicine or CM. You can see that from the data field Johnson et al were forced to use: “Other-Unproven: Cancer treatments administered by nonmedical personnel.” A lot of CM is administered by legitimate medical personnel, including physicians. That right there might be the source of under-ascertainment for purposes of this study.

Pseudoscientific medicine: A continuum

Proponents of integrative oncology, CAM, and integrative medicine often discuss “alternative medicine” use as though it were a different beast from “complementary medicine.” The reason is simple: Choosing unproven therapies instead of conventional medicine is inarguably bad in a physician’s mind, while advocates can do mental gymnastics to convince themselves that adding unproven treatments to conventional therapies is good, or at least not harmful. That’s why I like this point made by the authors:

Our work demonstrates that CM and alternative medicine likely represent entities along a continuum, rather than being distinct entities. Although we consider complementary (or integrative) medicine to integrate unproven nonmedical methods with conventional therapies, and alternative medicine as the use of unproven methods instead of conventional therapies, our work demonstrates that patients who use alternative medicine and CM are often behaving similarly in refusing conventional treatment. As a result, like the patients using alternative medicine (who do not undergo any initial CCT), patients using CM are also placing themselves in an unnecessarily greater risk of death by refusing some CCT.

Let me put this a slightly different way. When you integrate unproven medical therapies (or even outright quackery) with conventional science-based medicine, you do not make science-based medicine better, nor is there good evidence that adding pseudoscience to medicine entices significant percentages of patients who would have chosen to forego conventional therapy in favor of quackery into undergoing conventional therapy. As Johnson et al point out, it’s a continuum, and the patients who undergo CM, rather than rejecting conventional therapy in favor of quackery, are not as far down the path of pseudoscience as the patients who do reject conventional therapy, but they’re of the same mindset. It’s a matter of degree. Consequently, they are clearly more likely to refuse adjuvant therapy, and, if this study is replicated using other datasets, to die of their disease because of that refusal.

Anyone who reads this blog or my not-so-super-secret other blog knows that I am not a fan of alternative medicine. I’m also not a form of alternative medicine’s “more respectable cousins,” like CAM, CM, “integrative medicine,” and especially “integrative oncology.” It’s clear from numerous studies that alternative medicine does not have even a neutral effect on cancer survival; its effect is uniformly negative. This study strongly suggests that even just “integrating” such therapies into science-based oncology could have a pernicious effect on patient survival. At the very least, it suggests that integrating quackery with oncology doesn’t keep patients on the path of science-based treatment who would not already have used conventional treatment anyway, thus undercutting one of the most commonly used arguments by advocates of “integrative oncology”.