Not even two weeks after Donald Trump won the 2024 election, alarmed at what I was hearing about the new administration’s plans for the National Institutes of Health, I wrote a post entitled RFK Jr. vs. the NIH: Say goodbye to the greatest engine of biomedical research ever created. At the time, I crafted an intentionally (somewhat) hyperbolic title, simply to emphasize the potentially dire threat that the new administration posed to what is the crown jewel of biomedical research in the federal government, the NIH, which has generally enjoyed strong bipartisan support for many decades over many Presidential administrations. The impetus that led me to write the post was President-Elect Trump’s nomination of antivax activist and conspiracy theorist Robert F. Kennedy, Jr. as Secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), which I characterized—quite accurately, I think—as a catastrophe for public health and medical research. Another impetus was the speculation at the time that Dr. Jay Bhattacharya would be nominated as Director of the NIH, speculation that turned out to be accurate. Recall that Dr. Bhattacharya was one of the three co-authors of the Great Barrington Declaration, that October 2020 manifesto that called for letting SARS-CoV-2 rip through the “young and healthy” population in order to reach “natural herd immunity” in 3-6 months, further proposing that the elderly and those with chronic diseases that put them at high risk for severe disease and death from COVID-19 could supposedly be kept safe through a strategy of “focused protection.” It was, frankly, a social Darwinist strategy that never would have worked and was a disaster for public health.

At the time I wrote my post, I did wonder a bit whether I had been too harsh, too alarmist. Now I’m not so sure, given what has happened just during the first week of the new administration, which I’ll discuss in depth in a moment. However, I did have at my disposal what RFK Jr. himself had written as well as many of his “make America healthy again” (MAHA) cronies, such as RFK Jr. having said in 2023 (when he was still an independent Presidential candidate and before he had bent the knee to Donald Trump) that he wanted to “pause” drug development for infectious disease for eight years in order to focus on “chronic disease.” (Some have said that he also wanted to pause cancer drug development as well, but I couldn’t find evidence of this in the clip frequently cited.)

View on Threads

I pointed out that the NIH already does spend a lot of its budget for research into chronic diseases and that it’s an incredibly stupid idea to pause drug development in such a vital area, particularly given the current increasing problem we have with antibiotic-resistant bacteria; indeed, antibiotics have long been a neglected area of research, largely because antibiotics are not as profitable as other drug categories.

That background aside (the details of which I covered in my previous post), what is going on at the NIH since Donald Trump was inaugurated? Nothing good so far.

A gag order and travel ban

Anyone paying attention to the news knows that President Trump, upon taking office, issued a huge flurry of executive orders (EOs) covering a wide range of issues. Two days after Inauguration Day, Science published an alarming account of the new administration’s policies being implemented at NIH:

President Donald Trump’s return to the White House is already having a big impact at the $47.4 billion U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH), with the new administration imposing a wide range of restrictions, including the abrupt cancellation of meetings such as grant review panels. Officials have also ordered a communications pause, a freeze on hiring, and an indefinite ban on travel.

The moves have generated extensive confusion and uncertainty at the nation’s largest research agency, which has become a target for Trump’s political allies. “The impact of the collective executive orders and directives appears devastating,” one senior NIH employee says.

Today, for example, officials halted midstream a training workshop for junior scientists, called off a workshop on adolescent learning minutes before it was to begin, and canceled meetings of two advisory councils. Panels that were scheduled to review grant proposals also received eleventh-hour word that they wouldn’t be meeting.

“This kind of disruption could have long ripple effects,” says Jane Liebschutz, an opioid addiction researcher at the University of Pittsburgh who posted on Bluesky about the canceled study sections. “Even short delays will put the United States behind in research.” She and colleagues are feeling “a lot of uncertainty, fear, and panic,” Liebschutz says.

In fairness, the hiring freeze was government-wide. As for the panels scheduled to review grant proposals, those are commonly called study sections. Their purpose is to review grant applications and assign them a priority score for funding. That priority score is then used at the level of advisory councils, which make the actual funding decisions based on the priority scores of the grants and the priorities of the institutes of the NIH under which each grant application falls. (I described the process in detail a few weeks ago.)

I’ve been around a while, and I don’t recall the NIH ever having mass-canceled study section and advisory council meetings before when a new President took over. I asked around among researchers even more senior than I am, and no one could recall anything like this ever having been ordered by a newly inaugurated President before. Nor could any of them recall anything like this:

NIH travel chief Glenda Conroy sent an email to senior agency officials early today notifying them of an “immediate and indefinite” suspension of all travel throughout HHS with few exceptions, such as currently traveling employees returning home. Researchers who planned to present their work at meetings must cancel their trips, as must NIH officials promoting agency programs off site or visiting distant branches of the agency. “Future travel requests for any reason are not authorized and should not be approved,” the memo said.

The travel ban has left many researchers, especially younger scientists, bewildered, says a senior NIH scientist who asked to remain anonymous. Today, the scientist encountered one group of early-career researchers who were scheduled to attend and present at a distant conference next week—presentations that are now impossible. “People are just at a loss because they also don’t know what’s coming next. I have never seen this level of confusion and concern in people that are extremely dedicated to their mission,” the scientist says.

Presenting at scientific meetings is the lifeblood of researchers, particularly fellows and early career researchers, and there are a lot of research fellows working at NIH. I also wondered if the travel ban extended to travel to meetings funded by NIH grants for extramural researchers (researchers funded by the NIH who are not based at the NIH). Most NIH grants have a modest travel budget included to fund researchers presenting findings from the NIH-funded at scientific meetings. Worse, this order smacks of ideological suppression of any scientific communication that doesn’t jibe with the new administration’s ideology. Indeed, part of the order in the email referenced above states that NIH employees must “refrain from participating in any public speaking engagement until the event and material have been reviewed and approved by a Presidential appointee.” While brief communication freezes have been ordered by new administrations before, again, to my knowledge such bans have never before included presenting at scientific meetings.

Again, no one with whom I spoke could remember a travel ban this extensive ever having been ordered by a new President. One notes that this travel and communications blackout covers all federal health agencies, including the FDA and CDC. Indeed, for the first time in decades, the CDC did not publish its weekly MMWR:

3. To understand infectious risks, you have to have good data, carefully sourced and analyzed

Number 3 is why this week’s non-publication of the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR) came as such a shock. MMWR is the CDC’s primary way of publishing and communicating important data for public health. It didn’t go out because of a communications pause at federal health agencies issued by the new administration. The gap in publication marks the first time in its more than 60-year history that the CDC didn’t release a new issue.

And:

I put COVID-19 last because I strongly believe this is the primary motivation for the communications pause issued by the new administration. The pandemic was so horrifically disruptive — so traumatic — to our society that we’re still grappling with the best way to deal with it.

And one unfortunate coping mechanism is the urge to scapegoat individuals and organizations for what happened. The CDC and its publications were often in the center of this storm, and some now want to blame them for all that they were unhappy about.

Again, no new administration has ever done this before, as far as I have been able to ascertain. I have little doubt that the “champions of free speech” in the new administration are muzzling the CDC until they can find a way to control the message. Remember, Trump’s nominee to head the CDC is Dr. Dave Weldon, a former Florida Congressman and antivax activist from way back. One can easily imagine that the administration is shutting down CDC communications until it can install an antivaxxer as its director. Given that the CDC has been the focus of anger and resistance among COVID-19 contrarians and antivaxxers, one cannot help but wonder whether it is being targeted in retribution for that. Never mind that President Trump was in charge for most of the first year of the pandemic and that his administration instituted Operation Warp Speed, one of the worst-named vaccine initiatives ever, at least if you want to inspire public confidence in the vaccine or vaccines ultimately developed as a result. In any event, it is likely that Trump and RFK Jr. are scapegoating the CDC here. It’s also likely that they are scapegoating the NIH, given the outsized role that Dr. Anthony Fauci played in pandemic management as longtime director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), and, to a lesser extent, previous NIH Director Dr. Francis Collins. Consistent with this interpretation is President Trump’s decision last week to cancel Dr. Fauci’s security detail despite ongoing threats on his life.

The potential effects of these bans have, as you might imagine, been quite concerning to scientists. The Science article notes:

Previous administrations have imposed communications pauses in their first days. And the administration of former President Barack Obama continued a cap on attendance at scientific meetings first imposed by former President George W. Bush’s administration, which in some cases meant staff canceled trips to meetings.

But an immediate, blanket ban on travel is unusual, says one longtime researcher in NIH’s intramural program. “I don’t think we’ve ever had this and it’s pretty devastating for a postdoc or graduate student” who needs to present their work and network to move ahead in their career, the researcher says.

Another consequence of the communications pause, according to an NIH staffer involved with clinical trials at NIH’s Clinical Center, is that agency staff cannot meet with patient groups or release newsletters or other information to recruit patients into trials. Another unknown is whether NIH researchers will still be allowed to submit papers to peer-reviewed journals.

The NIH administers two main types of research programs. Its intramural research program consists of the scientists and physicians who work directly for the NIH carrying out biomedical research and clinical trials; the extramural research program, which is far larger, consists of the grants made to individual researchers (more specifically, to their universities for them to use to carry out the funded research). Again, as far as I can ascertain, no previous administration has ever prevented intramural researchers at the NIH from presenting their science or submitting abstracts for publication in the peer-reviewed biomedical literature.

There also seems to be an unanticipated consequence of the communications ban. Or maybe it was anticipated:

Scientists at the National Institutes of Health have been told the communications pause announced by the Trump Administration earlier this week includes a pause on all purchasing, including supplies for their ongoing studies, according to four sources inside the agency with knowledge of the purchasing hold.

The supply crunch follows a directive first issued on Tuesday by the acting director of the Department of Health and Human Services, which placed a moratorium on the release of any public communication until it had been reviewed by officials appointed or designated by the Trump Administration, according to an internal memo obtained by CNN. Part of this pause on public communication has been widely interpreted to include purchasing orders to outside suppliers. One source noted they had been told that essential requests can proceed and will be reviewed daily.

Researchers who have clinical trial participants staying at the NIH’s on-campus hospital, the Clinical Trial Center, said they weren’t able to order test tubes to draw blood as well as other key study components. If something doesn’t change, one researcher who was affected said his study will run out of key supplies by next week. If that happens, the research results would be compromised, and he would have to recruit new patients, he said.

And:

While it’s unclear if the communications moratorium was intended to affect purchasing supplies for NIH research, outside experts said the motivation wasn’t all that important.

“It’s difficult to tell if what’s going on is rank incompetence or a willful attempt to throw sand in the gears, but it really could be either, neither reflects well on them,” said Dr. Peter Lurie, who is president and executive director of the Center for Science in the Public Interest. Dr. Lurie was previously an official at the US Food and Drug Administration.

The clinical center only has a few weeks of medication on hand, according to a source who had knowledge of the pharmaceutical supply but was not authorized to speak with reporters.

Personally, I’m torn, wanting to fall back on the adage, “Never blame on malice what can be attributed to incompetence.” However, in this case I might make an exception. Unsurprisingly, Trump fans who understand that halting cancer research at the NIH campus, no matter how transiently, is politically not a good look, are claiming that “bureaucrats” are purposely overinterpreting Trump’s executive order to make Trump look bad; i.e., that holdovers from the previous administration are trying to sabotage the Trump transition. Hilariously, Richard “Lab Leak” Ebright thinks that not just the canceled purchasing is “sabotage,” but also the cancellation of meetings of study sections and advisory councils.

I tend to agree with this retort:

Exactly. If the order wasn’t really intended to shut down study sections and external ordering from intramural research programs, it would have been trivial to issue clarifying orders to exempt those activities. Again, is it incompetence or malice? I suspect that it’s a little of both, as I’m quite sure that Trump and his followers have a very specific kind of health research that they want so desperately to stop the NIH from ever funding again that they were willing to take radical action that risked making them look bad, with stories about cancer research being halted…excuse me, “paused.”

Worse, the EO canceling study sections will delay the awarding of research grants:

Chrystal Starbird, a cancer researcher at the University of North Carolina School of Medicine, had been preparing to serve on her first National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant review panel at the end of January. On Wednesday, to her surprise, that meeting was abruptly canceled.

These NIH panels, or “study sections,” typically involve a group of about 20 to 30 scientists who meet to assess research grant proposals within their areas of expertise. Most of the grants, Starbird says, range from about $2 million to $10 million. Once the group reviews and scores the projects, a separate NIH “advisory council” decides which ones to fund.

The email Starbird received was vague. It came from her study section contact at NIH, within the Trump administration, and it said the multiday meeting, set for January 30 and 31, would not take place as planned. The message instructed her to save her files about the projects for the time being and thanked her for her service to the NIH. “I’ve never seen a complete pause like this as part of a transition,” she told me.

Serving for the first time on an NIH study section is yet another milestone in a research career. Besides allowing one to network, serving on study sections helps a researcher learn what sorts of questions are most pressing in a field, where the research is going, and how to present a research plan in the most understandable, coherent manner possible.

More important, though, is how the delays could impact critical research. A brief delay might not have too serious an impact, but if the “pause” continues and more study sections fail to meet, it will start to have a huge impact on biomedical research at universities all over the country. Research programs, once “paused,” can be very difficult to restart again. (I have personal experience with this.) As I’ve said before, the NIH is the crown jewel of the entire biomedical research infrastructure of the federal government, an institution that other nations envy and that has long helped to keep the US at the forefront of biomedical research in the world.

Why? To help understand why Trump and the MAHA movement might target the NIH this way, it’s helpful to look at one of RFK Jr.’s chief apologists, a medical oncologist who once did somewhat interesting and useful research, before attacking those of us debunking medical pseudoscience like homeopathy and characterizing such efforts as being beneath his planet-sized intellect—e.g., “dunking on a 7′ hoop“—and then, during the pandemic, going full COVID-19 contrarian before embracing antivax talking points. Yes, I’m referring to Dr. Vinay Prasad.

Dr. Prasad: “Don’t worry, be happy” about the NIH under Trump

Given how much he clearly wants a position in the administration and, as a result, has been sucking up to RFK Jr. and Donald Trump, Dr. Prasad naturally published an article on his monetized Substack that should have been entitled “Don’t Worry, Be Happy,” but instead was entitled Pausing NIH study sections is going to be fine, after which he added, “In fact, it’s a good thing. The NIH needs reform.”

He begins by invoking—who else?—Dr. John Ioannidis, whom I used to admire but have watched with increasing alarm as, starting very early in the pandemic, he took a heel turn to become among the most contrarian of COVID-19 contrarians:

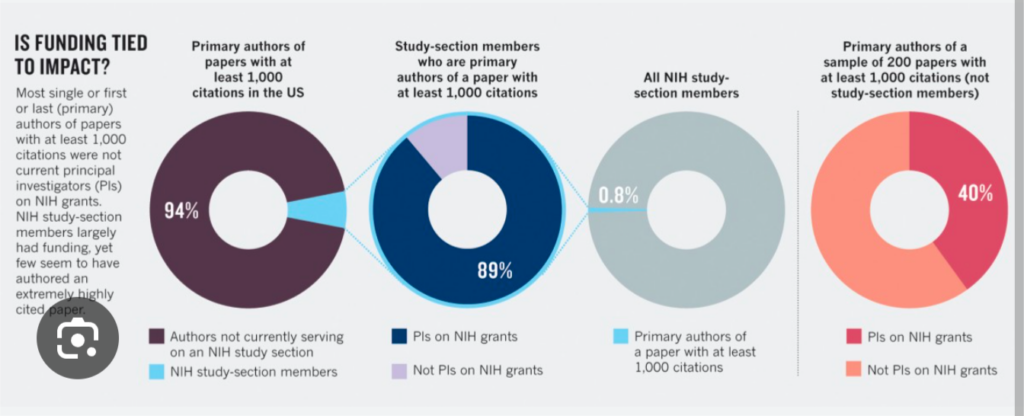

Panic unfolded yesterday as the NIH announced a pause in study sections. Study sections are groups of mediocre scientists who decide which grants are funded. You may bristle at my word choice of ‘mediocre’ but data support that claim. Here is research by Ioannidis in Nature:

He looked at authors of papers with more than 1000 citations. These are highly influential studies. I have published 530+ papers, but only one of mine fits this bucket. As such, I would make this group, but I would not have 2 years ago.

He compares this to study sections members and you can see the poor overlap. Ioannidis conclusion: conform and be funded. NIH seeks mediocre ideas that tread along established lines and not highly novel views. It does a bad job of funding people who do truly transformational work.

He included this image, but no direct citation:

I immediately recognized the paper cited by Dr. Prasad, as I had discussed it in detail a long time ago. First, it was a commentary—not a research paper—published in 2012 and entitled Conform and be funded. At the time Ioannidis had joined the long line of contrarians complaining about the NIH’s supposed funding and promotion of “mediocrity” and “conformity.” (Indeed, this was the first indication that perhaps my admiration of Dr. Ioannidis might be misplaced…nearly thirteen years ago!) His arguments were, as is often the case, highly exaggerated. First, most of the time, the examples cited of science that led to innovative treatments but whose investigators initially had difficulty getting NIH funding are often full of hindsight bias, in which now it seems obvious how brilliant the ideas were, even though at the time they were being considered it wasn’t at all obvious that they would turn out to be so transformative. (As we like to say in medicine, the retrospectoscope is 100% accurate.) I will note, as I always do when discussing this topic, that whenever NIH funding decisions become more conservative, it is usually be cause money is tight and study sections and advisory councils don’t want to make risky bets. The answer to that is to provide more funding. Does anyone want to take a guess whether Donald Trump will significantly increase NIH funding? More likely it will be quite the opposite. Of course, those complaining about conservative funding decisions at the NIH rarely provide workable solutions to try to correct that bias. Dr. Ioannidis was no exception then, and Dr. Prasad is no exception now.

In addition to his Substack article, Dr. Prasad has posted a half-hour video, which I had a hard time watching because his unrelenting smugness irritates me so much:

Indeed, on X, the hellsite formerly known as Twitter, Dr. Prasad is using scientists who have been affected by the administration’s actions to attack the NIH:

Worse, it was likely in response to a snitch tag:

I note that Dr. Prasad could have made the same point after expressing empathy for Dr. Chuong, but he did not. Instead, he castigated the researcher for “not having a broader perspective.” (Sure, don’t be upset that your chance to present your proposal to the NIH for funding was canceled. It’s all for the greater good.) In one other case, Dr. Prasad offers a bit of empathy—sort of, but it comes across as fake. Why? Because he immediately launches into his usual attacks:

Of course, no one is arguing that an enormous amount of time is spent writing grant applications. I myself have written several in the last few years that haven’t been funded, and it is frustrating. That’s not what this is about, as you might get an indication when observing how Dr. Prasad’s fans leapt in:

Back to Dr. Prasad’s Substack:

Trump has paused study sections to allow future NIH director Jay Bhattacharya to revisit the priorities. This is completely normal and reasonable. Jay might decide to run a randomized trial testing the current study section structure against proposed alternatives, such as the modified lottery, and other ideas.

I tackled the whole question of modified lottery versus other methods of determining who gets research grants in great detail, so much detail that I suspect I’ve thought about the concept far more deeply than Dr. Prasad ever has. In fact, I know that I have, as Dr. Prasad shows no sign of knowing much, if anything, about the background data and research that already exist comparing different systems for determining which grant applications are funded. Indeed, after considering seriously Dr. Prasad’s promotion of “modified lottery” and the evidence that exists for it, I concluded that NIH study sections are far from the waste of time portrayed by Dr. Prasad and that they do distinguish scientifically meritorious proposals from those that are lacking. The problem is that they just aren’t a fine enough measure to reliably distinguish between excellent proposals; e.g.., which of two clearly excellent proposals is better. Nor was I against adding the element of a lottery to choosing among proposals that are highly meritorious whose success and output the current system doesn’t predict accurately. Again, improving the scientific rigor of the grant application process is not what Dr. Prasad is about, however. He’s about supporting Dr. Bhattacharya and pulling out of his nether regions unworkable ideas for “randomized studies” of different systems for determining which grants to award that sound profound but in reality are profoundly unserious. Of course, he’s not making these proposals for an audience of scientists. He’s making them for an audience of ideologues who don’t know how vaccine schedules are constructed or how the NIH works.

Indeed, in his video, Dr. Prasad demonstrates more ignorance:

It’s even worse than that. NIH dollars come with massive indirects which make researchers who have a lot of NIH dollars untouchable. Universities usually overlook their errors and keep them on faculty because they get a lot of cash. That cash is then laundered by universities given back to them in unrestricted slush funds used for all sorts of purposes including lavish travel and parties and going out for lab meetings. It’s wasted we don’t know what happens to all that money.

Tell me you’ve never been awarded an NIH grant before without telling me you’ve never been awarded an NIH grant before. Yes, universities do sometimes give back part of the “indirect costs” to researchers for a fund to help fund their lab, usually to buy equipment, particularly to well-funded researchers. (The NIH is notoriously stingy funding equipment purchases.) By way of background for those not familiar with NIH grants, indirects are the costs over and above the dollar amount of direct costs that go to fund the research. Basically, the part of the budget for indirect costs goes to the university to help fund the infrastructure used by its researchers. I would never deny that there is a legitimate argument to be had over whether indirects can be excessive and add way too much to the cost of research funded by grants. (In some cases, they can be 70% of the direct costs added to the overall grant; also, indirect cost rates are periodically negotiated by each university with the NIH.) That’s not what Dr. Prasad is about, though. He’s trying to portray NIH funding and indirects as gross waste. The above is gross exaggeration that portrays well-funded researchers as, in essence, fraudsters living high on the hog off of NIH grant money. To say that this is divorced from reality is a massive understatement. Let’s just put it this way. I haven’t had an NIH R01 in over a decade, and even back then it was incredibly difficult to spend the funds on anything other than what the budget said they would be spent on. If you wanted to change that, you had to file a new budget and have it approved.

Even Dr. Wafik El-Deiry, a respected senior researcher whom I once admired but who of late has been a little too credulous regarding antivax claims of “turbo cancer” due to COVID-19 vaccines, found this hard to swallow:

Then, of course, Dr. Prasad blamed the dreaded DEI (Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion) initiatives so hated by Donald Trump and his followers, because of course he did:

And what about diversity? The whole creation of the DEI state at universities is in part due to NIH indirects. There are NIH diversity supplements that Trump has argued that are going to get cut. So of course naturally a new administration with new priorities an economist-physician coming to power will look at this in a very different way and while he’s doing that there should be a pause on grants. Tt’s not that big a deal. Science is not going to fall by the wayside. Universities have redundant budgets.

Here’s the thing. Previous administrations have had “new priorities” that they wanted to implement at NIH. None of them stopped study section and advisory council meetings dead in their tracks right after assuming power. Ironically, at least Dr. Prasad recognizes that Dr. Bhattacharya is not a scientist, but rather a physician who is also an economist. (I also note that Dr. Bhattacharya is also a physician who has never done a residency and hasn’t treated patients since he graduated from medical school.) One wonders why the current administration considers such an action so critical that it has done what, as far as I can tell, no past administration has ever done before, and “paused” study section and advisory council meetings until, if you believe Dr. Prasad, it can shut down DEI supplements. It makes me think that this is what the pause is really about, not increasing the scientific rigor of the NIH grant approval process. (Thanks, Dr. Prasad, for being totally honest about what is really going on and how much you approve!) Worse, from my limited anecdotal experience, I’m beginning to think that universities have clearly gotten the message. I’ve heard through the grapevine reports of universities scrambling to rename any office or research program that includes the words “equity” or “inclusion” in its title to a name without those words in a frantic effort to avoid the crackdown that is coming. And who can blame them? Unfortunately, I suspect that the thought police in the administration won’t take long to catch on to this tactic.

One of the worst things about what is going on since Trump became President again is that I see a real possibility that a very important area of medical research, health disparities research, will be conflated with the dreaded “DEI.” Indeed, it appears to be already happening, as Dr. Prasad gives away the game with his extreme dismissiveness of current disparities research. While he doesn’t attack health disparities research in his Substack post, he spends quite a bit of verbiage in his video ranting about disparities research, simplifying it grossly and absurdly:

I got into a bit of a spat online today where someone was defending cancer health disparities research. What did I say? My argument is simple. Do I think poor people do worse than rich people? Yes. Do I think black people, Hispanic people, do worse than white people? Yes, in part mediated because they tend to be poor; so poverty is not good for having cancer. Being a minority is not good for having cancer. That’s been shown 1, 2, 12, 2,000, 1,000, 100,000—it’s been shown 100,000 times in the literature. it’s been shown over and over again but what can you do about it?

He then goes on to complain that we don’t need any more research showing disparities because health disparities all boil down to basically the caricature presented above. It’s a view so utterly simplistic as to be risible. Basically, Dr. Prasad categorizes disparities research in its current form as a waste of money because it doesn’t use what he considers sufficiently “rigorous” methods to test interventions to overcome differences in outcome based on socioeconomic factors. (Yes, his “RCTs or it’s crap” evidence-based medicine (EBM) methodolatry and fundamentalism are on full display here.) His arrogance, as usual, is also on display. He thinks he knows more about health disparities research than actual experts in health disparities, and, as a result, characterizes it all as useless other than his very simplistic caricature of what health disparities research tells us about how different racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic groups fare much differently when suffering from different diseases or about their overall susceptibility to disease. Basically, he’s dismissing any research that doesn’t meet his arbitrary standards as not being crap not worth funding or doing. He portrays nearly all disparities research as a big scam, a waste of money that furthers the careers of researchers more than it helps patients. While there might be a germ of a point under all the opprobrium, it’s twisted, exaggerated, and filled with anger and contempt.

For example, here he’s not entirely incorrect that economics is a bit part of disparities. The problem is…well, read:

Trump so far is doing a lot of good things. If you were objective about it and actually thinking, does the NIH need someone to kick the crap out of it and reform it? Absolutely. Does DEI and these modules got to go? Absolutely. Should diversity be funded to say that poor people do worse than rich people, black people do worse than white, people over and over and over? No. We need solutions. You’ve got to solve that problem and a lot of that solution is not going to come from medicine it’s going to come from socioeconomics and from the economic and political sector.

Even if you accept Dr. Prasad’s premise, do you also accept that the Trump administration is likely to do anything in the socioeconomic sector to address health and healthcare disparities fueled by economic inequity? It boggles the mind that anyone would believe this, given Trump’s long history of having no interest whatsoever in these topics, other than as grievances. Personally, I don’t think that even Dr. Prasad believes this. He just doesn’t like DEI and views disparities research as useless.

MAHA vs. the NIH

It’s a very depressing time to be a biomedical researcher; that is, unless you are aligned with the new administration. I’ve referred to what is being advocated by the Trump administration as the new Lysenkoism. If you don’t believe that, then why would an administration—any administration—shut down..excuse me, “pause”… grant reviews in progress when no other administration has done that before upon assuming power, even ones that wanted to “reform” NIH? These proposals are about control. They are about punishing scientists who don’t toe the ideological line with respect to the science preferred by the administration, which will be dictated by people who got nearly everything wrong about the pandemic and whose ranks are populated with outright antivaxxers. The proposals to “test” new methods of distributing grants strike me more as a means of justifying doling out federal research dollars to researchers aligned with MAHA and MAGA ideology, rather than truly increasing the scientific rigor. It’s all consistent with the antivax and quack conspiracy theory narrative that portrays the NIH as doling out grants the way Vito Corleone (and, later, his son Michael) doled out favors to underlings in return for loyalty in the classic mafia film The Godfather. It’s just that now there’s a new Godfather running things, and he will dole out grant money favors according to the degree of loyalty to anti-DEI initiatives. I fear that much-needed outcomes and disparities research will fall victim to the anti-DEI meat grinder of this administration.

And don’t even get me started on what might be in store for the CDC and the entire US vaccination program. That might be a topic for a future post, particularly given that RFK Jr.’s first confirmation hearing is this week, although it would likely be an even more depressing post than this one.