Can a bionic retinal implant paired with high-tech glasses restore sight in patients with age-related macular degeneration? An article in a recent issue of the New England Journal of Medicine described an attempt to do so (the article is behind a paywall for most of you).

The results were encouraging, but preliminary.

Age-Related Macular Degeneration

Age-related macular degeneration (ARMD) is the most common cause of irreversible vision loss in older Americans. Severe vision loss can occur via two main pathways. The wet form of macular degeneration is the result of abnormal blood vessels growing under the retina. This form can progress rapidly. There are now several drugs that, when injected into the eye, can significantly reduce the vision loss in wet ARMD.

Dry ARMD is the more common form. Among patients with dry ARMD, geographic atrophy (GA) is responsible for the most severe vision loss. I wrote 2 previous articles here and here about Pegcetacoplan (Syfovre), a new treatment for geographic atrophy that, in my opinion, was approved despite lackluster data from the clinical trials. Subsequently, a second drug, avacincaptad pegol (Izervay), has been FDA-approved with similarly dubious clinical trial results.

None of the medical treatments for GA are capable of restoring vision that has already been lost.

About the retina

The retina is the light-sensing tissue of the eye. It lines the inner wall of the eye like wallpaper. The macula is a specialized region of the retina, and corresponds to the “straight-ahead” portion of vision. It contains the highest density of photoreceptors. The macula is selectively damaged by ARMD.

The above figure is a simplified “wiring diagram” of the retina. Light enters the eye and traverses the retina from the top of the figure to the bottom. When visible light interacts with the retina, the photoreceptors (rods and cones) are activated. The photoreceptors transduce light energy into electrical signals. The photoreceptors pass the electrical signal on to the bipolar cells, which pass the signal to the ganglion cells. The ganglion cells have long extensions (dendrites) that form the optic nerve and travel all the way back to the brain.

Geographic Atrophy: when things go wrong

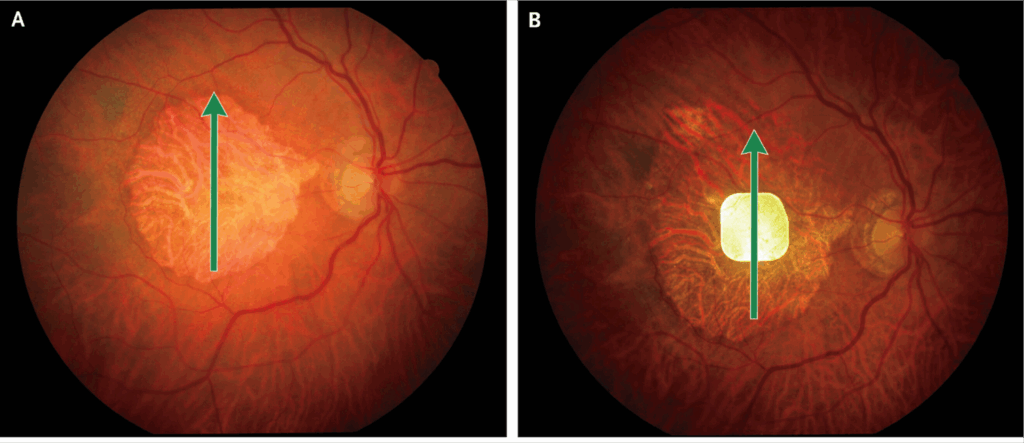

In the geographic atrophy form of ARMD, the photoreceptors and retinal pigment epithelial cells in the macula die. This is a progressive condition resulting in blind spot(s) in or near the center of the visual world of the patient. These can greatly impact the ability to perform tasks such as reading, driving, recognizing faces, and navigating through daily activities. Currently available medical treatments for geographic atrophy aim to slow down the growth of geographic atrophy, but are unable to reverse it.

Toward a bionic retina

The device described in the NEJM article is called the Photovoltaic Retina Implant Microarray (PRIMA). “Photovoltaic” refers to the process of converting light into electrical signals. Solar panels are the most prevalent examples of photovoltaic devices. The PRIMA device is surgically implanted under the retina in regions where the photoreceptors are missing. This, in theory, allows the PRIMA device, when exposed to light, to produce and transfer electrical impulses to the bipolar cells, simulating the function of photoreceptors. The bipolar cells then stimulate the ganglion cells, which communicate with the brain via the optic nerve.

The photovoltaic implant is only one link in the system. The patient must also wear high-tech eyeglasses that capture images and convert those images to infrared light. That light is projected onto the implant, which powers the electrical stimulation of the bipolar cells. The signal is passed on to ganglion cells, then to the brain via the optic nerve. Since infrared light activates the PRIMA chip, but not the photoreceptors, the creators of the implant explain, this system allows the patient to use the PRIMA system without interfering with the native vision from healthy portions of the retina.

Photo of the glasses paired with the PRIMA implant. Glasses consist of a front-facing camera, a pocket processor, and a rear-facing infrared projector.

The Clinical Trial

The study was a multi-center open-label study without an external control group. The primary endpoint was a “clinically meaningful” improvement in vision at 1 year post-implant compared to baseline. Clinically meaningful was defined by a pre-specified proportion improvement in central visual acuity (measured size of letters that could be read).

Results

38 participants received the implant and 32 were assessed at 12 months.

The good

81% of the participants evaluated at 12 months met the threshold for clinically meaningful vision improvement. The average improvement in vision was impressive. After one year, participants could read letters about 1/3 the size they could see before the implant.

The bad

The surgical procedure to implant the PRIMA is not trivial. There were 26 serious adverse events, mostly related to the surgery. Most of these resolved spontaneously or were successfully treated. It is likely that with greater experience and refinement of the procedure, adverse event rates will decrease.

The uncertain

The study included a questionnaire to measure vision-related quality of life. Such surveys are now standard in many clinical trials. The data from the quality of life surveys are reported in a Supplementary Appendix to the article. Different domains were tested (eg, emotional, mobility, reading, overall). The results were not impressive. None of the domains achieved statistically significant improvement.

The authors point out that the study was not powered to detect changes in quality of life. This is true, however, given the substantial improvement in vision among the participants, one might have expected larger responses in quality-of-life activities such as reading and mobility. This raises concern that the changes in vision measured under the conditions of the clinical trial may not translate directly into meaningful gains in real-world activities. Further research will undoubtedly explore this question.

Summary

This study demonstrates proof of concept of a technology that may allow patients to recover vision for conditions that were previously thought to be irreversible. This is an exciting study that will surely stimulate further research. The real-world impact of this technology, as well as longer-term safety and efficacy studies should be explored.